AMIDST all the great pulp thrills and features in Sky Fighters, they ran a true story feature collected by Ace Williams wherein famous War Aces would tell actual true accounts of thrilling moments in their fighting lives! This time we Australian flyer—Capt. Allan R. Kingsford!

Captain Kingsford enlisted as a  simple private in the Australian Army. The troop ship carrying his contingent was torpedoed by a German submarine and he was cast adrift in a heaving sea at midnight with only a frail spar to buoy him up. He served for over a year as a Lance Corporal of Infantry in Mesopotamia, he determined upon obtaining a transfer to the Hying corps, and after many setbacks he finally was ordered for flight training and sent to England, He became pilot of the Zeppelin night patrol guarding London, later joining that strange organization, the British Independent Air Force, as a bombing pilot attached to 100 Squadron. As a member of that group which served under no army, but roved about from point to point, he took part in 270 night bombing raids and became known as the Ace of night bombers. This account of his most thrilling flight is taken from his private memoirs.

simple private in the Australian Army. The troop ship carrying his contingent was torpedoed by a German submarine and he was cast adrift in a heaving sea at midnight with only a frail spar to buoy him up. He served for over a year as a Lance Corporal of Infantry in Mesopotamia, he determined upon obtaining a transfer to the Hying corps, and after many setbacks he finally was ordered for flight training and sent to England, He became pilot of the Zeppelin night patrol guarding London, later joining that strange organization, the British Independent Air Force, as a bombing pilot attached to 100 Squadron. As a member of that group which served under no army, but roved about from point to point, he took part in 270 night bombing raids and became known as the Ace of night bombers. This account of his most thrilling flight is taken from his private memoirs.

DESTROYING THE BOULAY AIRDROME

by Captain Allan R. Kingsford • Sky Fighters, November 1936

BOULAY! That is a name to conjure up grim thoughts. Boulay Airdrome … the home nest of the Hun Gothas that rained so much terror on Paris and London! When our C.O. told us Intelligence had discovered that the Hun Gothas were planning to put on a massive parade over Paris that bright August night and that 100 Bombing Squadron had been ordered to forestall their show, Bourdegay (my observer) and I danced with glee.

We had tried to destroy Boulay before but something had always been against us . . . bad weather, tricky engines, faulty bombs or too many enemy planes and archies for protection, that we had failed in our efforts. Still Bourdegay and I thought it could be done.

Loaded with sixteen bombs I took off with my flight at midnight and flew over the valley of the Moselle River toward Boulay 90 kilometers behind the front lines. Because of the great distance there and back (180 kilometers) I knew it would have to be a short show on a hot spot. We would have no time to waste when we got there, and we would have to go down through hell fire and brimstone to lay our iron eggs.

Lights Flash on!

Flying at a great height, masked by a convenient layer of clouds that hid our approach from the enemy, I managed to guide the formation intact right over Boulay. Our “Fees” (slang for F.F. 2B’s, the type of bomber they flew) were running perfectly that night.

Just as we appeared over the airdrome the take-off lights on the field flashed on. There were the flights of Gothas running across the field in take-off just below us! And all lit up conveniently like churches for us to pepper at!

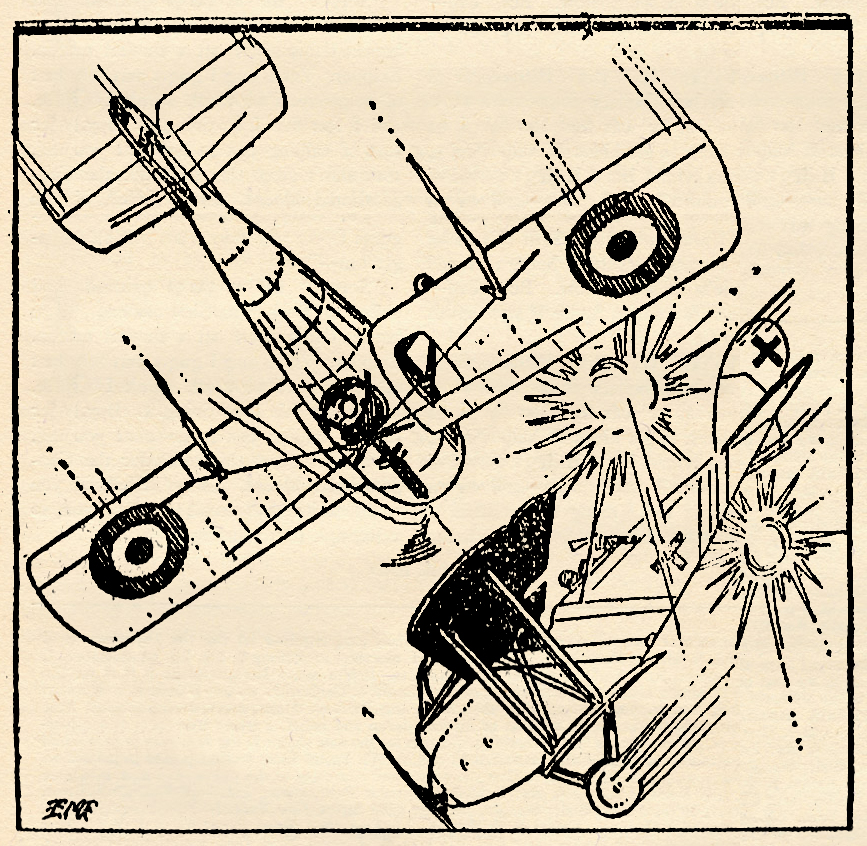

Bourdegay hooped and yelled at me to dive down on the nearest one. I threw the Fee into a steep dive. A searchlight flashed on, another and another. The landing field went suddenly dark! The wind whined through the brace wires and struts of my diving plane like shrieking demons, A searchlight beam caught us full. Archie puffs blazed clear as Christmas lights around us. I slipped the Fee, tried to get out of that dazzling light, but the searchlight crew held us in their beam. “I’m going for them!” Bourdegay yelled, swinging his Lewis around and spewing out a long burst.

There was a dazzling flash. The searchlight seemed to explode, spread apart like a pinwheel in a million dazzling fragments. The Gotha ahead of us showed its red exhausts. I was down to three hundred feet now and almost over it. Other “Fees” were following behind me. I could hear the snort of the motors above the roar of my own. Machine-guns on the ground opened up in murderous volley, their tracer streams shooting up like light rays from a setting sun. “Pull her up!” Bourdegay yelled, bending over his bomb sights while his fingers tensed on the trips. I pulled back and he let go. A direct hit! The Gotha exploded in red flames.

I zoomed for the ceiling with all the sauce I had, managed to get up to a thousand feet before another probing finger of light caught up. Bourdegay had dropped two more pills on the way up. One set a hangar on fire. Another exploded on the field and hurled up a geyser of earth which a running Gotha tore into and up-ended on its nose.

Crashing Bullets

I slid the Fee again, but couldn’t escape the beam. Bullets crashed through my wings. Archie blasts rocked us mercilessly. I banked and zig-zagged, stood on my wingtips and dropped three hundred feet, but I couldn’t shake that light; so I determined on a ruse. I dropped a landing flare through the tube, cutting my engines at the same time. It exploded in flame beneath the plane. The Hun gunners thought they had made a direct hit on my ship. They ceased firing and the searchlight beam swung away seeking my mates.

All was bedlam now below on the earth and in the skies above. Boulay Airdrome was in flames. Fed by a fitful wind the flames leaped this way and that, igniting one hangar after another. Several of the Gothas, however, had succeeded in getting into the air.

Bourdegay spied one of these and yelled at me to go for it. He still had two bombs left.

A Fountain of Flame

I sent the Fee around in a split air turn, straightened out and streaked for the running Gotha. Just as I got over it a fountain of flame blossomed under my wings—flaming onions! Up they came like luminous dumbbells in their crazy, erratic trajectory. I lifted the nose and leaped over them, then piqued for the Gotha. Bourdegay tripped his first bomb. It missed.

But the second made a direct hit. The Gotha fell apart in the flame-ridden sky. And just in time—for a formation of night flying enemy fighters thundered in from the east, swarming around my flight like bees and attempting to cut off our return.

Boulay was destroyed, however! We had accomplished our mission. Not a Gotha reached Paris that night, nor any night thereafter. We had scotched that last parade before it began.

How Bourdegay and me got back, I don’t know. I guess we were just lucky, for most of the boys with us did not return.

the second of three Three Mosquitoes stories we’re presenting this month. The Mosquitoes fame had spread to such an extent on the Western Front that the German high command had issued a general order to get them, alive or dead. To cool things down, our impetuous trio has been temporarily reassigned to the British East African front. While on patrol the trio is hit by a violent tropical storm and separated. Kirby finds himself swept out over the Indian Ocean. After a confrontation with a Zeppelin he tried to take with him, Kirby is forced to land on a scraggy rock in the middle of the ocean. Marooned. His only company the skeletons of the island’s previous visitors, until—it turns out he did bring down the zeppelin, unfortunately the german crew of said zeppelin find themselves marooned on the same rock! From the December 1st, 1929 number of War Birds, it’s The Three Mosquitoes vs the “Spawn of Devil’s Island!”

the second of three Three Mosquitoes stories we’re presenting this month. The Mosquitoes fame had spread to such an extent on the Western Front that the German high command had issued a general order to get them, alive or dead. To cool things down, our impetuous trio has been temporarily reassigned to the British East African front. While on patrol the trio is hit by a violent tropical storm and separated. Kirby finds himself swept out over the Indian Ocean. After a confrontation with a Zeppelin he tried to take with him, Kirby is forced to land on a scraggy rock in the middle of the ocean. Marooned. His only company the skeletons of the island’s previous visitors, until—it turns out he did bring down the zeppelin, unfortunately the german crew of said zeppelin find themselves marooned on the same rock! From the December 1st, 1929 number of War Birds, it’s The Three Mosquitoes vs the “Spawn of Devil’s Island!”

simple private in the Australian Army. The troop ship carrying his contingent was torpedoed by a German submarine and he was cast adrift in a heaving sea at midnight with only a frail spar to buoy him up. He served for over a year as a Lance Corporal of Infantry in Mesopotamia, he determined upon obtaining a transfer to the Hying corps, and after many setbacks he finally was ordered for flight training and sent to England, He became pilot of the Zeppelin night patrol guarding London, later joining that strange organization, the British Independent Air Force, as a bombing pilot attached to 100 Squadron. As a member of that group which served under no army, but roved about from point to point, he took part in 270 night bombing raids and became known as the Ace of night bombers. This account of his most thrilling flight is taken from his private memoirs.

simple private in the Australian Army. The troop ship carrying his contingent was torpedoed by a German submarine and he was cast adrift in a heaving sea at midnight with only a frail spar to buoy him up. He served for over a year as a Lance Corporal of Infantry in Mesopotamia, he determined upon obtaining a transfer to the Hying corps, and after many setbacks he finally was ordered for flight training and sent to England, He became pilot of the Zeppelin night patrol guarding London, later joining that strange organization, the British Independent Air Force, as a bombing pilot attached to 100 Squadron. As a member of that group which served under no army, but roved about from point to point, he took part in 270 night bombing raids and became known as the Ace of night bombers. This account of his most thrilling flight is taken from his private memoirs. Mosquitoes—the unseasonably warm weather has brought the Mosquitoes out of hibernation to help get through the cold winter months, at Age of Aces dot net it’s our fourth annualMosquito Month! We’ll be featuring that wiley trio in three early tales from the Western Front. To start things off we have a tale featuring Travis from 1928. There are no secrets between The Three Mosquitoes—if that’s the case, then what’s Travis been doing on his early morning test runs? That’s what the impetuous Kirby and his pal Shorty want to find out. And they get more than a proverbial worm when they’re up with the “Early Birds.” From War Novels, October 1928—

Mosquitoes—the unseasonably warm weather has brought the Mosquitoes out of hibernation to help get through the cold winter months, at Age of Aces dot net it’s our fourth annualMosquito Month! We’ll be featuring that wiley trio in three early tales from the Western Front. To start things off we have a tale featuring Travis from 1928. There are no secrets between The Three Mosquitoes—if that’s the case, then what’s Travis been doing on his early morning test runs? That’s what the impetuous Kirby and his pal Shorty want to find out. And they get more than a proverbial worm when they’re up with the “Early Birds.” From War Novels, October 1928—

a story from the prolific pen of Mr. Robert J. Hogan—the author of

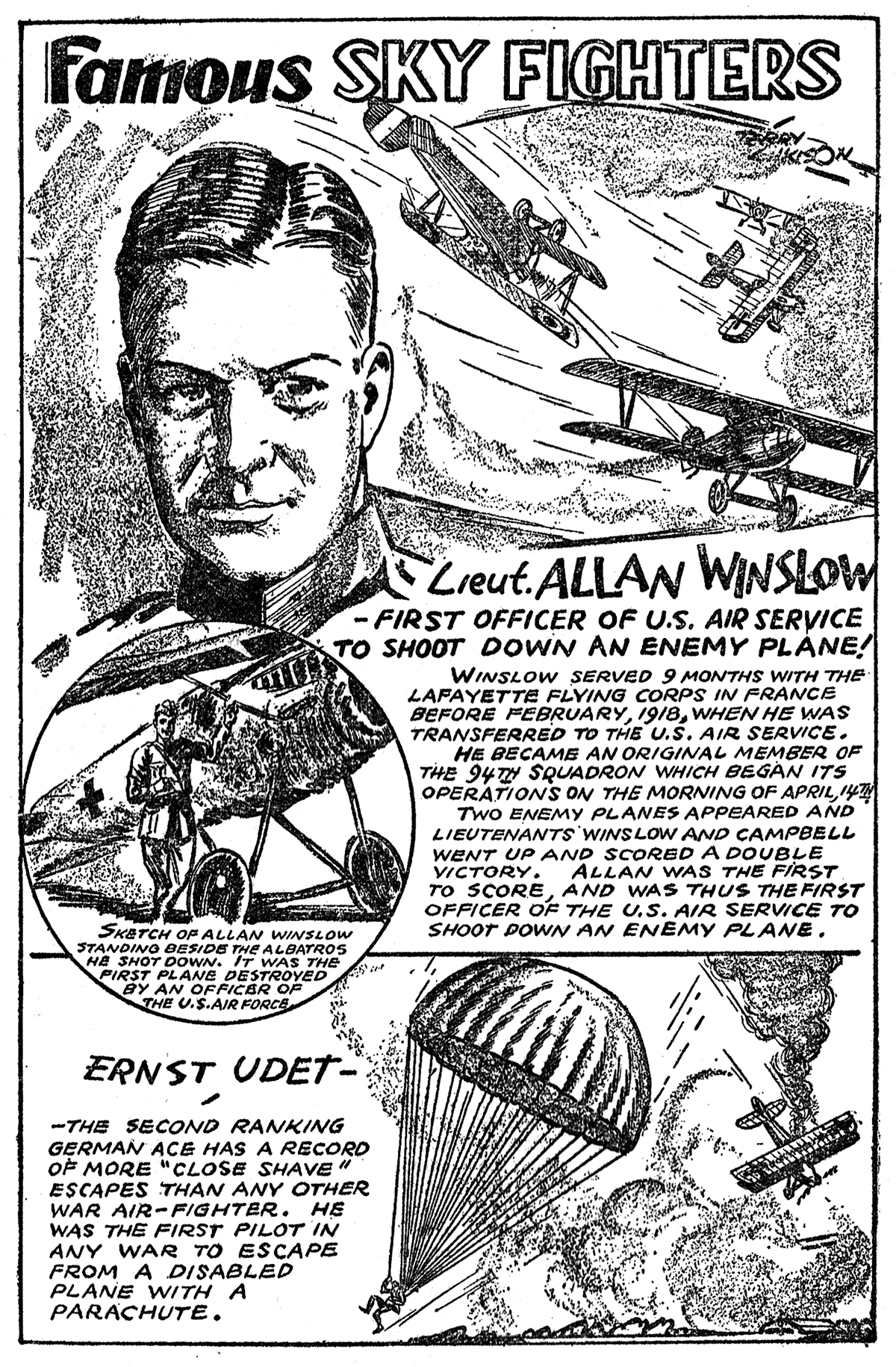

a story from the prolific pen of Mr. Robert J. Hogan—the author of  of fortune. Born and raised In Aaheville, N. Carolina, young Rockwell got the wanderlust soon after graduating from the University of Virginia. When the Germans made their surprise move on the forts of Liege, Rockwell was serving in the ranks of the Foreign Legion. For a heroic exploit in hand to hand bayonet fighting, he was awarded the Medaille Militaire. For a whole year he served with the Foreign Legion in the trenches, then transferred to the aviation and went into training at Avord. When Norman Prince formed the first American Flying Squadron in Paris, Rockwell was one of those invited to join. He proved out to be one of the best and most daring pilots of that original band. His career was cut short by his untimely death on September 23rd, 1916.

of fortune. Born and raised In Aaheville, N. Carolina, young Rockwell got the wanderlust soon after graduating from the University of Virginia. When the Germans made their surprise move on the forts of Liege, Rockwell was serving in the ranks of the Foreign Legion. For a heroic exploit in hand to hand bayonet fighting, he was awarded the Medaille Militaire. For a whole year he served with the Foreign Legion in the trenches, then transferred to the aviation and went into training at Avord. When Norman Prince formed the first American Flying Squadron in Paris, Rockwell was one of those invited to join. He proved out to be one of the best and most daring pilots of that original band. His career was cut short by his untimely death on September 23rd, 1916.

had a story in a majority of the issue of Flying Aces from his first in January 1930 until he returned to the Navy in 1942. Starting in August 1931, they were stories featuring the weird World War I stories of Philip Strange. But in November 1936, he began alternating these with sometime equally weird present day tales of espionage Ace Richard Knight—code name Agent Q. After an accident in the Great War, Knight developed the uncanny ability to see in the dark. Aided by his skirt-chasing partner Larry Doyle, Knights adventures ranged from your basic between the wars espionage to lost valley civilizations and dinosaurs. Knight is sent to Spain to get the American military men out of the Spanish Cival War, only to find the mysterious Four Faces—a criminal cabal that seek to control all crime on the earth—trying to turn La Guerra Civil into another World War with America taking all the blame!

had a story in a majority of the issue of Flying Aces from his first in January 1930 until he returned to the Navy in 1942. Starting in August 1931, they were stories featuring the weird World War I stories of Philip Strange. But in November 1936, he began alternating these with sometime equally weird present day tales of espionage Ace Richard Knight—code name Agent Q. After an accident in the Great War, Knight developed the uncanny ability to see in the dark. Aided by his skirt-chasing partner Larry Doyle, Knights adventures ranged from your basic between the wars espionage to lost valley civilizations and dinosaurs. Knight is sent to Spain to get the American military men out of the Spanish Cival War, only to find the mysterious Four Faces—a criminal cabal that seek to control all crime on the earth—trying to turn La Guerra Civil into another World War with America taking all the blame! a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author and venerated newspaper man—Frederick C. Painton.

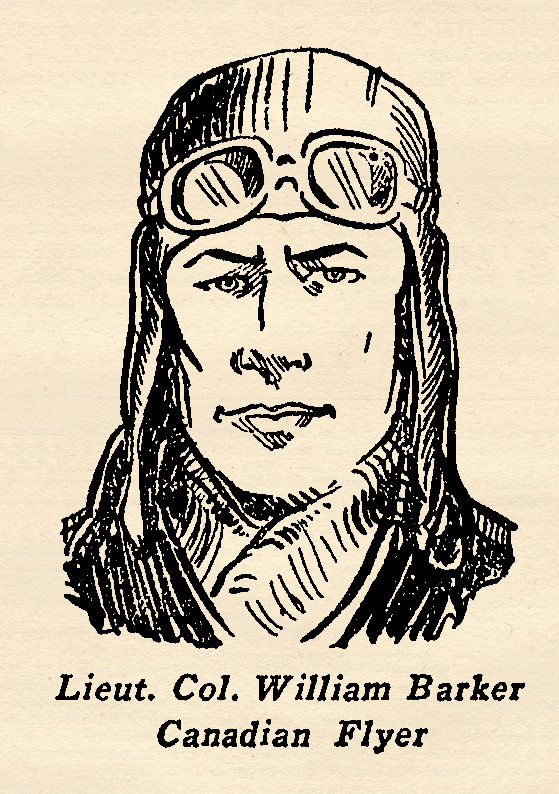

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author and venerated newspaper man—Frederick C. Painton. of William Barker’s career on two flying fronts reads more like fiction than fact. Born in the prairie province of Manitoba in 1894, he enlisted as a Private in the Canadian Army at the age of 19. He served in the cavalry before transferring to the flying corps. Barker began as a simple private. But he skyrocketed swiftly through all the grades to that of Lieut. Colonel. His training for a pilot was limited to two flights with an instructor. After that he was turned loose to begin piling up an amazing record. On October 27, 1918, he crowned this amazing record with the most astounding aerial feat of the whole war . . . fighting and escaping from a surrounding net of 6O enemy planes at the dizzy altitude of 20,000 feet.

of William Barker’s career on two flying fronts reads more like fiction than fact. Born in the prairie province of Manitoba in 1894, he enlisted as a Private in the Canadian Army at the age of 19. He served in the cavalry before transferring to the flying corps. Barker began as a simple private. But he skyrocketed swiftly through all the grades to that of Lieut. Colonel. His training for a pilot was limited to two flights with an instructor. After that he was turned loose to begin piling up an amazing record. On October 27, 1918, he crowned this amazing record with the most astounding aerial feat of the whole war . . . fighting and escaping from a surrounding net of 6O enemy planes at the dizzy altitude of 20,000 feet.

a story by prolific pulpster—Arthur J. Burks! Burks was a Marine during WWI and went on to become a prolific writer for the pulps in the 20’s and 30’s. He was a frequent contributor to Sky Fighters. Here we have a story of Frank Tracy, a strict flight leader who rules his troops with threats of court-martial or other disciplinary action. Tracy uses his methods as a way of keeping his flight safe, but they see him as just hiding behind his flight to save his own hide. As is the case in these situations tempers reach a boiling point! From the June 1933 issue of Sky Fighters, it’s Arthur J. Burks’ “Martinet.”

a story by prolific pulpster—Arthur J. Burks! Burks was a Marine during WWI and went on to become a prolific writer for the pulps in the 20’s and 30’s. He was a frequent contributor to Sky Fighters. Here we have a story of Frank Tracy, a strict flight leader who rules his troops with threats of court-martial or other disciplinary action. Tracy uses his methods as a way of keeping his flight safe, but they see him as just hiding behind his flight to save his own hide. As is the case in these situations tempers reach a boiling point! From the June 1933 issue of Sky Fighters, it’s Arthur J. Burks’ “Martinet.”

You heard right! That marvel from Boonetown, Iowa is back! And this time we find that Knight of Calamity finds himself shrieking amongst the sheiks in “Doin’s in the Dunes” from the pages of the March 1936 Flying Aces.

You heard right! That marvel from Boonetown, Iowa is back! And this time we find that Knight of Calamity finds himself shrieking amongst the sheiks in “Doin’s in the Dunes” from the pages of the March 1936 Flying Aces.