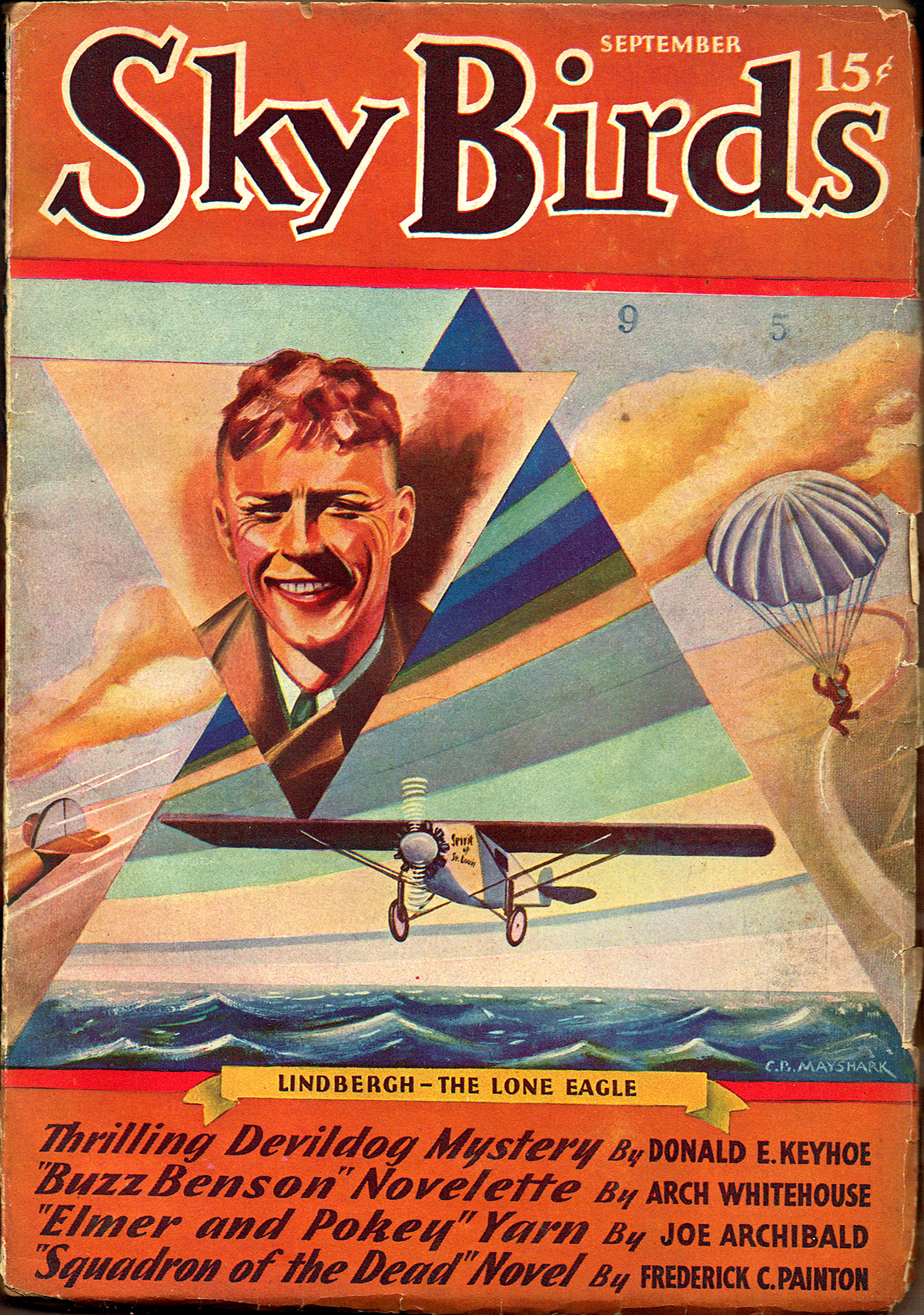

“Flying Aces, February 1936″ by C.B. Mayshark

THIS May we are once again celebrating the genius that is C.B. Mayshark! Mayshark took over the covers duties on Flying Aces from Paul Bissell with the December 1934 issue and would continue to provide covers for the next year and a half until the June 1936 issue. While Bissell’s covers were frequently depictions of great moments in combat aviation from the Great War, Mayshark’s covers were often depictions of future aviation battles and planes, like January 1936’s thrilling story behind its cover is a tribute to Pan American as it spans the Pacific!

Pan American Spans the Pacific

MAN has fulfilled one of the most ambitious dreams of modern transportation! He has conquered the Pacific. Giant, four-engined Pan-American flying boats now ply in regular passenger and mail flights from California to China, with intermediate stops at Hawaii, Midway, Wake, Guam, and the Philippines. People are flying across the world’s vastest body of water in some 60 hours of flying time, whereas hardly yesterday such a journey consumed the greater part of a month.

MAN has fulfilled one of the most ambitious dreams of modern transportation! He has conquered the Pacific. Giant, four-engined Pan-American flying boats now ply in regular passenger and mail flights from California to China, with intermediate stops at Hawaii, Midway, Wake, Guam, and the Philippines. People are flying across the world’s vastest body of water in some 60 hours of flying time, whereas hardly yesterday such a journey consumed the greater part of a month.

To be sure, people now make this momentous flight for the novelty of it. But tomorrow the whole matter will be routine. It will be accepted in the same manner as the rising generation takes airplanes and radio for granted.

It’s possible that the passengers who make the inaugural flights in the clipper ships will be under the delusion that they are pioneers of some sort who possess in abundance that fortitude required to undertake hazardous adventures. Unfortunately, however, they’ll be wrong if they think so, for the real pioneering will have been long since completed when they board the speedy aircraft that will link the Occident with the Orient. In fact, there will be no hazardous elements whatsoever attached to their venture—the real pioneers have seen to it that the line offers the maximum of security.

“Still, we might satisfy the ego of the initial passenger by making a concession. We might, with a stretch of the imagination, term him an armchair adventurer. And when we say “armchair adventurer,†we mean just that. For as the huge China Clipper streaks across the Pacific skies, our friend will be slouched comfortably in an upholstered chair, tilted so that the maximum restfulness is assured. From this point of vantage, he can gaze out of the windows at toy objects thousands of feet below—ships. Or he can read his favorite magazine or book, play a hand of bridge, write a letter, doze off for a nap, or . . . . oh, well, he can do any one of a dozen pleasant things. Be assured that Pan-American has it all figured out.

And our hero doesn’t have to worry about navigation, radio communication, gas consumption, engine control, wind velocity, or any other of the hundred and one things which are checked constantly. There is a first-rate pilot, co-pilot, and radio operator in the control cabin attending to all of these things for him. And those men are the finest of their profession in the world. They have seen years of experience on the extensive routes of Pan-American in the Caribbean and in Latin and South America. They have intensive schooling in flight and theory behind them.

But there are other and more important elements which enter into the picture. The officials of Pan-American didn’t decide overnight to establish a transpacific air route. It is much more involved than that. As far back as early 1931, the project was outlined and experimentation launched. Juan Trippe, president of Pan-American Airways; Andre Priester, the line’s chief engineer, and Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh together conceived the idea of the Pacific run and directed the actual work. There were many angles to be considered—route, type of ship, fueling bases, servicing stations, ad infinitum. By the merest chance, the islands which were the most logical stepping stones for such a flight are in the possession of the United States.

And so the work of fitting out the island stations was started. On March 27, 1934, the steamer North Haven steamed out from the Golden Gate with enough equipment on board to establish five air bases—and the bases were built and in running order in four months’ time. One of the islands—Wake—heretofore has been devoid of human life. Radio and power equipment as well as food and knock-down houses had to be transported and set up. But the work progressed step by step, with the result that in a few months’ time a complete island air depot existed on a speck of rock and coral which had never before supported human beings.

At the same time that the route was being studied and laid out, the problem of the type of ship to fly over it was being considered. A large part of the Pan-American equipment consists of Sikorskys and it was logical that a new Sikorsky be built for the Pacific route. About a year ago the S-42 was completed and given her trial runs over the already established Caribbean routes. When it was decided that the new ship possessed the requirements for a trans-Pacifie run, it was brought to the West Coast and on April 15 a crew headed by Captain Edwin C. Musick took her off the water at San Francisco and headed her for Honolulu, 2,400 miles away. Several test flights over the Pacific were made in the new Sikorsky, and so thorough had been the planning and laboratory work that even these first trips were accomplished exactly according to schedule.

But when regular mail and passenger flights commence, a ship other than the Sikorsky will be put into service. Early in October, Pan-American accepted delivery from the Glen L. Martin Co. of the largest flying boat ever to be built in this country. The ship has been christened the China Clipper and it is this new huge, four-motored flying boat that’will see service on the new route.

AND so it can be seen that if our friend lounging in a comfortable armchair tilted back at the angle which most serves his convenience and gazing out of the windows of the streaking China Clipper has any fears, they are only imaginary. But very likely he will still insist that what he is doing parallels the feats of the pioneers in the early 1800’s. And that’s okay with us and probably with the officials of Pan-American, too.

The real story of the trans-Pacific conquest, to our way of thinking, centers upon the formidable work accomplished in laying the foundations of the line. The real heroes are the squads of men who struggled in the face of many hardships to construct the island stations in order that those who now fly the long route may enjoy the securities and conveniences which are one with modern transportation.

Flying Aces, February 1936 by C.B. Mayshark

Pan American Spans the Pacific: Thrilling Story Behind This Month’s Cover

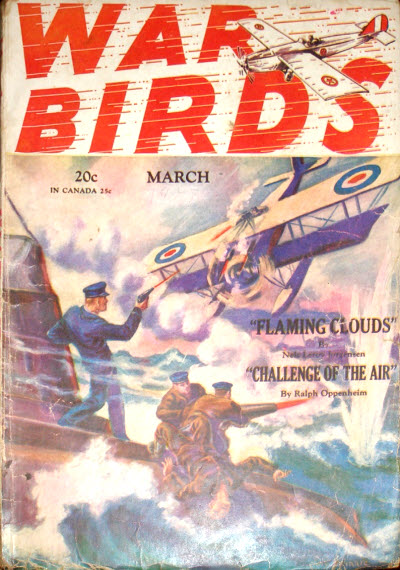

hit the stands in February 1928, it not only contained an exciting tale of Ralph Oppenheim’s inseparable trio The Three Mosquitoes, but it also had a rare factual piece by Mr. Oppenheim. Ralph and his younger brother Garrett had taken a trip to Europe the previous year and just happened to be there at the right time to be able to get to Paris and be there at Le Bourget Field on the 21st of May when Charles Lindbergh successfully ended his trans-Atlantic flight!

hit the stands in February 1928, it not only contained an exciting tale of Ralph Oppenheim’s inseparable trio The Three Mosquitoes, but it also had a rare factual piece by Mr. Oppenheim. Ralph and his younger brother Garrett had taken a trip to Europe the previous year and just happened to be there at the right time to be able to get to Paris and be there at Le Bourget Field on the 21st of May when Charles Lindbergh successfully ended his trans-Atlantic flight!