Introducing The Three Mosquitoes!

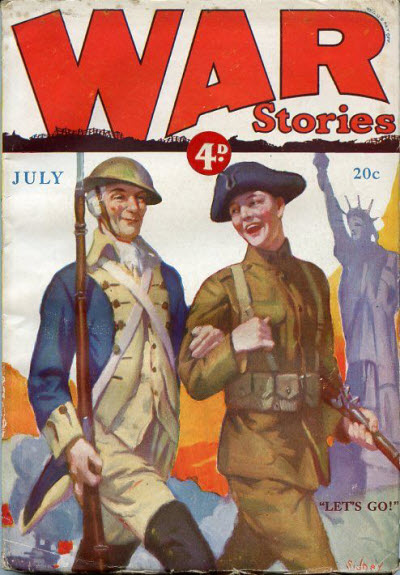

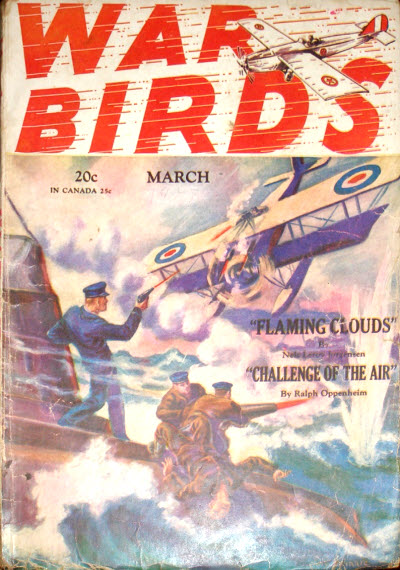

MARCH is Mosquito Month! We’re celebrating Ralph Oppenheim and his greatest creation—The Three Mosquitoes! We’ll be featuring three early tales of the Mosquitoes over the next few Fridays as well as looking at Mr. Oppenheim’s pre-pulp writings. So, let’s get things rolling, as the Mosquitoes like to say as they get into action—“Let’s Go!”

The greatest fighting war-birds on the Western Front are once again roaring into action. The three Spads flying in a V formation so precise that they seemed as one. On their trim khaki fuselages, were three identical insignias—each a huge, black-painted picture of a grim-looking mosquito. In the cockpits sat the reckless, inseparable trio known as the “Three Mosquitoes.” Captain Kirby, their impetuous young leader, always flying point. On his right, “Shorty” Carn, the mild-eyed, corpulent little Mosquito, who loved his sleep. And on Kirby’s left, completing the V, the eldest and wisest of the trio—long-faced and taciturn Travis.

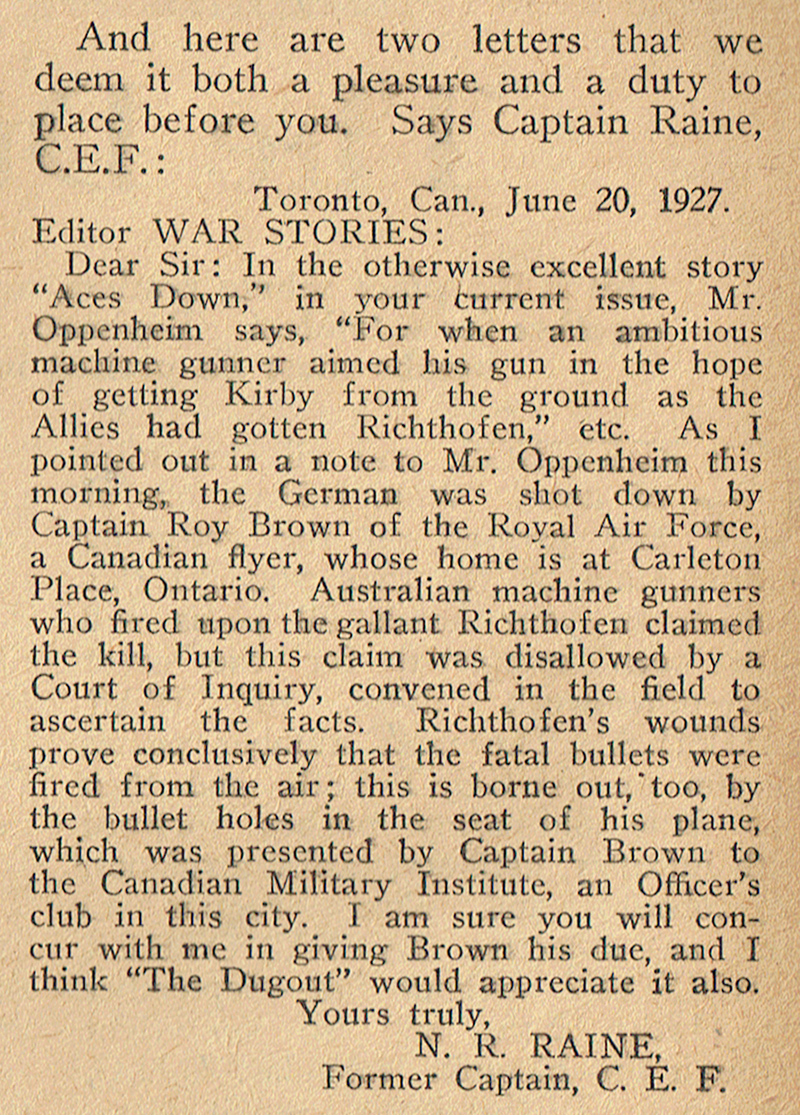

Were going to  get things off the ground with Oppenheim’s very first Three Mosquitoes tale from the pages of War Stories from July 1927! This premier tale finds the inseparable trio separated following a stunting attack on the front line trenches that resulted in Carn and Travis going down behind enemy lines and captured and an humiliated Kirby being sent down to ferrying new ships to their assigned fields. Mindless, boring work for the beaten Ace—his instructions are to avoid all altercations and steer far clear of any action what so ever. Especially since the plane he’s flying and those of the other ferried ships have no guns! But that doesn’t stop Kirby when he sees the Block brothers sniffing around the very secluded forrest the Allies are amassing troops and supplies—he tries to find a way to stop them from getting that information back across the lines without the benefit of guns!

get things off the ground with Oppenheim’s very first Three Mosquitoes tale from the pages of War Stories from July 1927! This premier tale finds the inseparable trio separated following a stunting attack on the front line trenches that resulted in Carn and Travis going down behind enemy lines and captured and an humiliated Kirby being sent down to ferrying new ships to their assigned fields. Mindless, boring work for the beaten Ace—his instructions are to avoid all altercations and steer far clear of any action what so ever. Especially since the plane he’s flying and those of the other ferried ships have no guns! But that doesn’t stop Kirby when he sees the Block brothers sniffing around the very secluded forrest the Allies are amassing troops and supplies—he tries to find a way to stop them from getting that information back across the lines without the benefit of guns!

Kirby was an Ace, a fighter, and today they had him “ferry-piloting,” without guns. If the enemy showed, he was supposed to keep out of it. And then the enemy showed, and Kirby, the Ace, the born fighter, forgot those hateful orders, forgot that he had no guns! A splendid, thrilling story of the airmen.

- Download “Aces Down!” (July 1927, War Stories)

If you find yourself wanting to read more exploits of the intrepid trio, we’ve posted a number of the adventures of the Three Mosquitoes during past Mosquito Months, including several of their exploits from their first year:

It was against orders, but Kirby and his pals weren’t worrying about that. They wanted to meet that big German formation—and Kirby wanted to give battle to the “Black Devil,” the famous German Ace. A splendid flying story.

- Download “High Diving” (August 5, 1927, War Stories)

The C.O. of the flying field was sore—the Three Mosquitoes, dare-devils supreme were doing their “grand-stand stuff” again. But when the C.O. found himself in difficulties, with Boche planes swarming all around him—things were different. The best flying story of the month.

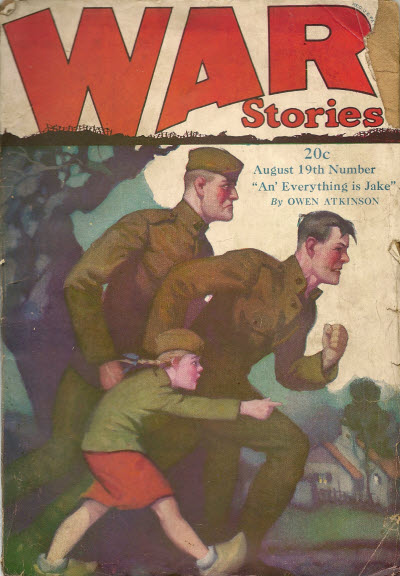

- Download “Down form the Clouds” (August 19, 1927, War Stories)

Here again is Kirby, the great leader of the “Three Mosquitoes.” The pilot of the new Fokker knew every trick, and Kirby matched him—then went into straight fighting. A brilliant air story—and one that is totally different.

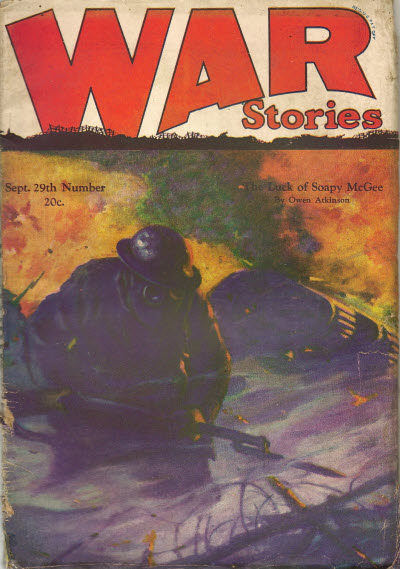

- Download “Devils of the Air” (September 29, 1927, War Stories)

If you enjoyed these tales of our intrepid trio, check out some of the other stories of The Three Mosquitoes we have posted by clicking the Three Mosquitoes tag or check out one of the four volumes we’ve published on our books page! A fifth volume will be out later this year. And come back next Friday or another exciting tale.

the pulps takes place at an Army Arsenal, whose innocent-looking buildings housed enough T.N.T. to blow up a fair-sized city. Although every safety precaution had been put in place, it seemed disaster was unavoidable when a letter arrived from an anarchist:

the pulps takes place at an Army Arsenal, whose innocent-looking buildings housed enough T.N.T. to blow up a fair-sized city. Although every safety precaution had been put in place, it seemed disaster was unavoidable when a letter arrived from an anarchist: published pulp story was another aviation tale, this time for the pages of Dell’s War Stories for April 1927. In this second tale, John Slade is posted at an American base in France. Slade is to take a photographer over the lines in a two-seater observation crate without an escort in hopes of getting vital pictures of a ruined town the German’s are presently holding that the Allies want to take. Slade is an exceptional, daredevil pilot perfect for the job—his only fear is using a parachute! And this job may require that if he can’t get through the German’s A.A. guns and any planes they may send out to shoot them down. Will he be able to face his fears when the time comes?

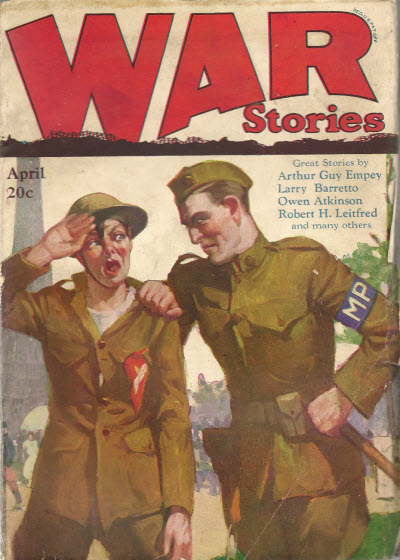

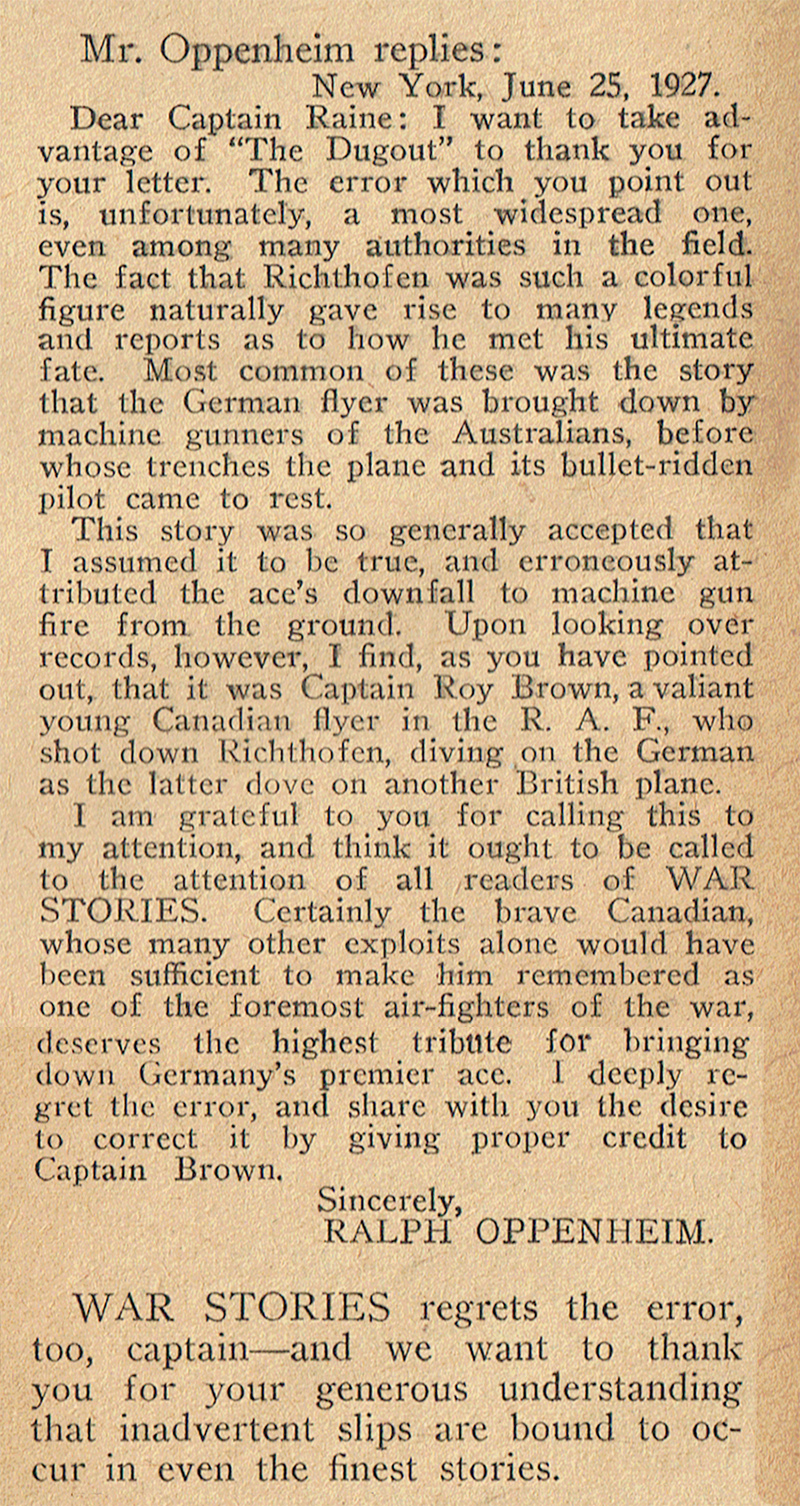

published pulp story was another aviation tale, this time for the pages of Dell’s War Stories for April 1927. In this second tale, John Slade is posted at an American base in France. Slade is to take a photographer over the lines in a two-seater observation crate without an escort in hopes of getting vital pictures of a ruined town the German’s are presently holding that the Allies want to take. Slade is an exceptional, daredevil pilot perfect for the job—his only fear is using a parachute! And this job may require that if he can’t get through the German’s A.A. guns and any planes they may send out to shoot them down. Will he be able to face his fears when the time comes?  hit the stands in February 1928, it not only contained an exciting tale of Ralph Oppenheim’s inseparable trio The Three Mosquitoes, but it also had a rare factual piece by Mr. Oppenheim. Ralph and his younger brother Garrett had taken a trip to Europe the previous year and just happened to be there at the right time to be able to get to Paris and be there at Le Bourget Field on the 21st of May when Charles Lindbergh successfully ended his trans-Atlantic flight!

hit the stands in February 1928, it not only contained an exciting tale of Ralph Oppenheim’s inseparable trio The Three Mosquitoes, but it also had a rare factual piece by Mr. Oppenheim. Ralph and his younger brother Garrett had taken a trip to Europe the previous year and just happened to be there at the right time to be able to get to Paris and be there at Le Bourget Field on the 21st of May when Charles Lindbergh successfully ended his trans-Atlantic flight!

the second of three exciting tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, The Three Mosquitoes past comes back to haunt them when the brother of the Black Devil, whom they dispatched in last week’s story, sends a challenge to Kirby in hopes of avenging his death!

the second of three exciting tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, The Three Mosquitoes past comes back to haunt them when the brother of the Black Devil, whom they dispatched in last week’s story, sends a challenge to Kirby in hopes of avenging his death! off the ground with what was believed to have been the first flight of the Three Mosquitoes. I say believed because according to both Robbin’s Index and the online

off the ground with what was believed to have been the first flight of the Three Mosquitoes. I say believed because according to both Robbin’s Index and the online

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

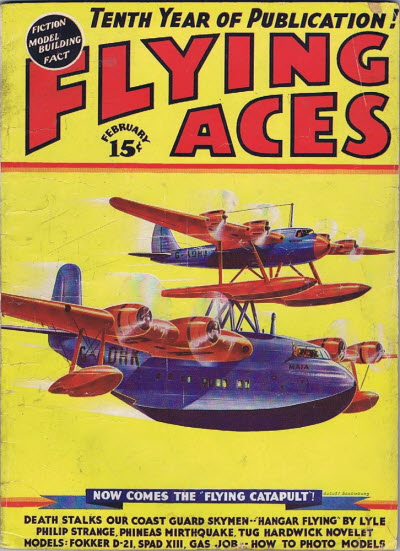

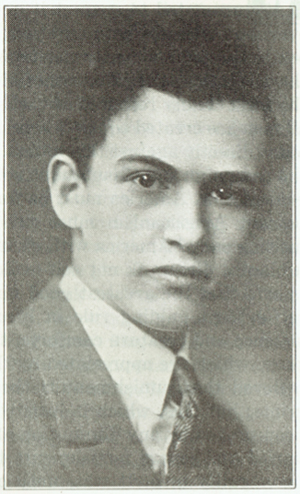

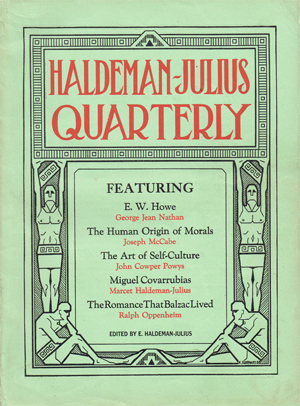

The premiere issue of the Quarterly (October 1926) featured many articles from current and upcoming publications, including Ralph’s “The Love-Life of George Sand.” In some of the early press for the article, they refer to Ralph as being sixteen years old—and, although he could have written it when he was sixteen—he most likely wrote it when he was eighteen, since the hype for it started before he turned nineteen. Ralph’s “The Love-Life of George Sand” article is actually just a reprinting of the 64 page little blue book of the same name. Both the Little Blue Book and the Quarterly were published in 1926.

The premiere issue of the Quarterly (October 1926) featured many articles from current and upcoming publications, including Ralph’s “The Love-Life of George Sand.” In some of the early press for the article, they refer to Ralph as being sixteen years old—and, although he could have written it when he was sixteen—he most likely wrote it when he was eighteen, since the hype for it started before he turned nineteen. Ralph’s “The Love-Life of George Sand” article is actually just a reprinting of the 64 page little blue book of the same name. Both the Little Blue Book and the Quarterly were published in 1926.

THE author of “The Love-Life of George Sand” is nineteen years old. Here is one of America’s future authors already at work, beginning to express himself with freshness and vigor, with finish and style; an artist to the tips of his fingers. It is one of the purposes of the Quarterly to bring out the best work of young America, and in accepting Ralph Oppenheim’s study we believe we are giving space to material of first-rate significance. This essay compares favorably with the best work we have ever accepted from mature, experienced writers. We did not take Ralph Oppenheim’s manuscript because he happens to be only a boy in years; rather were we influenced by the sureness of his touch. His age came up for comment only after we were satisfied that his work was well done. . . The Quarterly boasts that all in America is not jazz, noise and fury; a minority speaks vigorously and clearly, with intelligence, understanding, humor and craftsmanship. Ralph’s essay helps prove this assertion. Read young Oppenheim’s study and you will realize how important it is for the United States to have a magazine the purpose of which will be to go out and seek for the best from the talented and intelligent minority, bringing out new gifts, fresh viewpoints and sound work. First credit must, of necessity, go to Ralph himself; second credit must go to his artist-mother, Gertrude Oppenheim, and his poet father, James Oppenheim; third credit, in all fairness, must go to the Quarterly for opening its columns to a new voice. America will hear much from Ralph Oppenheim. He has something to say; he knows how to say it; he is a civilized human being, a complete answer to the charge that all of America has been reduced to stifling mediocrity, to unimaginative standardization. There is enough to complain about, in all truth, without crying that all is lost. Let us protest against the viciousness and stupidity of the superstitious majority, the hypocrisy and cowardice of its leaders, the mawkishness of our bunk-ridden millions—yes, let us aim our spitballs at our shams and fakirs, but let us, by all means, recognize worthy talent when we see it and lend an ear to the emerging youngsters who are breaking away from the herd and learning to stand as free individuals. Turn now to Ralph’s essay. At first you will marvel that it was written by a boy, but after a few paragraphs you will forget its author and fly along with his tonic and captivating work. . . . The portrait of George Sand was drawn especially for the Quarterly by Mrs. James Oppenheim, Ralph’s mother.

THE author of “The Love-Life of George Sand” is nineteen years old. Here is one of America’s future authors already at work, beginning to express himself with freshness and vigor, with finish and style; an artist to the tips of his fingers. It is one of the purposes of the Quarterly to bring out the best work of young America, and in accepting Ralph Oppenheim’s study we believe we are giving space to material of first-rate significance. This essay compares favorably with the best work we have ever accepted from mature, experienced writers. We did not take Ralph Oppenheim’s manuscript because he happens to be only a boy in years; rather were we influenced by the sureness of his touch. His age came up for comment only after we were satisfied that his work was well done. . . The Quarterly boasts that all in America is not jazz, noise and fury; a minority speaks vigorously and clearly, with intelligence, understanding, humor and craftsmanship. Ralph’s essay helps prove this assertion. Read young Oppenheim’s study and you will realize how important it is for the United States to have a magazine the purpose of which will be to go out and seek for the best from the talented and intelligent minority, bringing out new gifts, fresh viewpoints and sound work. First credit must, of necessity, go to Ralph himself; second credit must go to his artist-mother, Gertrude Oppenheim, and his poet father, James Oppenheim; third credit, in all fairness, must go to the Quarterly for opening its columns to a new voice. America will hear much from Ralph Oppenheim. He has something to say; he knows how to say it; he is a civilized human being, a complete answer to the charge that all of America has been reduced to stifling mediocrity, to unimaginative standardization. There is enough to complain about, in all truth, without crying that all is lost. Let us protest against the viciousness and stupidity of the superstitious majority, the hypocrisy and cowardice of its leaders, the mawkishness of our bunk-ridden millions—yes, let us aim our spitballs at our shams and fakirs, but let us, by all means, recognize worthy talent when we see it and lend an ear to the emerging youngsters who are breaking away from the herd and learning to stand as free individuals. Turn now to Ralph’s essay. At first you will marvel that it was written by a boy, but after a few paragraphs you will forget its author and fly along with his tonic and captivating work. . . . The portrait of George Sand was drawn especially for the Quarterly by Mrs. James Oppenheim, Ralph’s mother. The second issue of the Haldeman-Julius Quarterly (January 1927) featured Oppenheim’s “The Romance That Balzac Lived: How The Great Interpreter of the Human Comedy Lived and Loved” (a reprinting of The Romance That Balzac Lived: Honore de Balzac and the Women He Loved (lbb-1213, 1927)). The article was nicely illustrated with a daguerreotype of Balzac and spot illustrations by Fred C. Rodewald, but no introductory page about Oppenheim.

The second issue of the Haldeman-Julius Quarterly (January 1927) featured Oppenheim’s “The Romance That Balzac Lived: How The Great Interpreter of the Human Comedy Lived and Loved” (a reprinting of The Romance That Balzac Lived: Honore de Balzac and the Women He Loved (lbb-1213, 1927)). The article was nicely illustrated with a daguerreotype of Balzac and spot illustrations by Fred C. Rodewald, but no introductory page about Oppenheim. Oppenheim seemed to be a role with the Haldeman-Julius Quarterly readers (or at least their editors), for the third issue (April 1927) once again featured an article by Oppenheim. This time it was his treatise on his generation: “The Younger Generation Speaks: An American Youth Tells About Its Attitude Toward Life” (a reprinting of

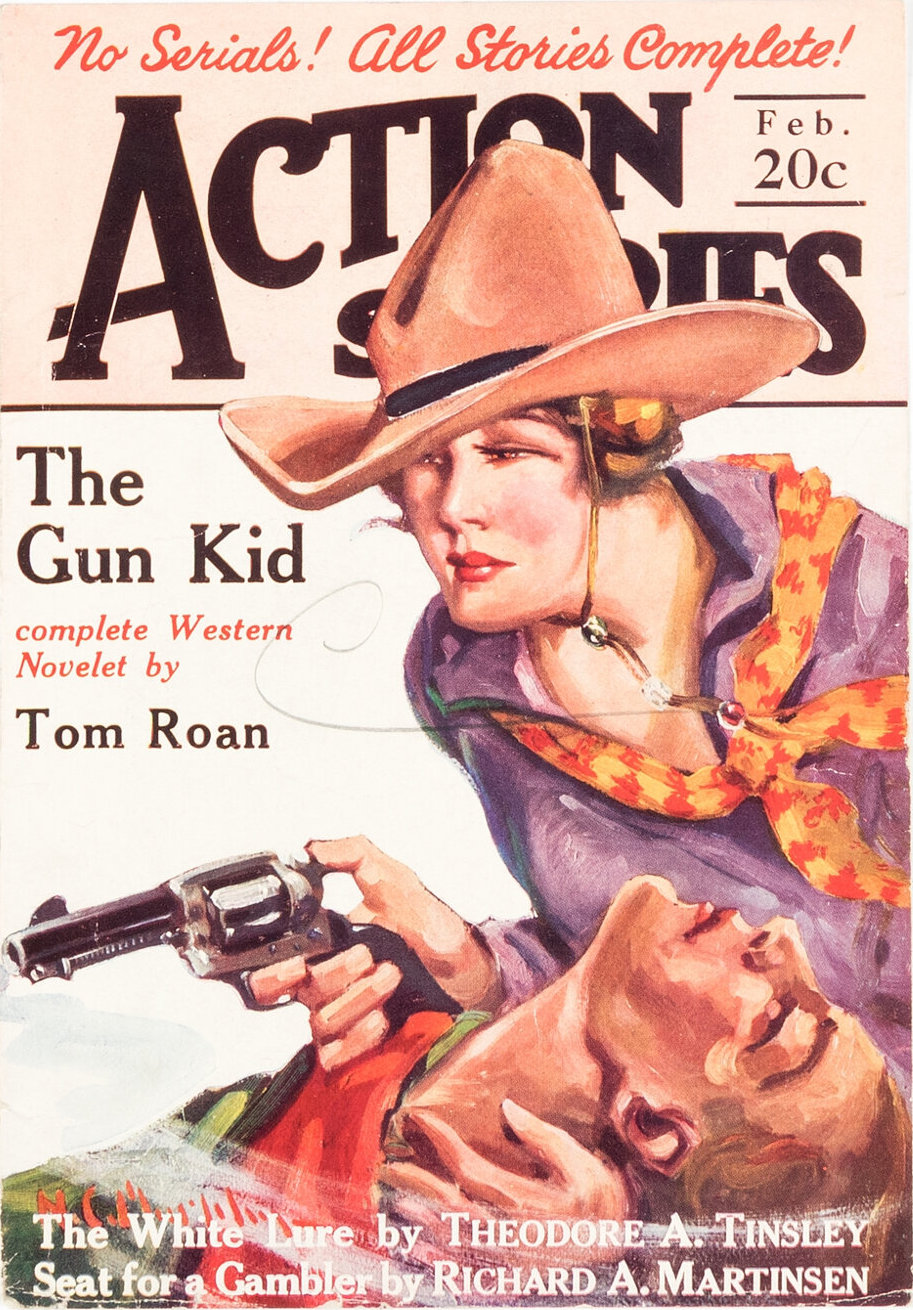

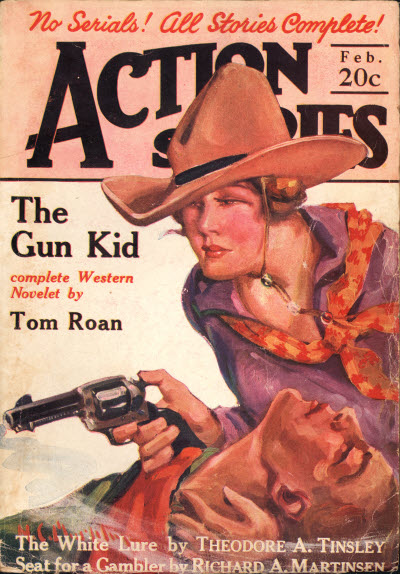

Oppenheim seemed to be a role with the Haldeman-Julius Quarterly readers (or at least their editors), for the third issue (April 1927) once again featured an article by Oppenheim. This time it was his treatise on his generation: “The Younger Generation Speaks: An American Youth Tells About Its Attitude Toward Life” (a reprinting of  His first published story was a taunt tale of aviation and death he titled “Doom’s Pilot” in the pages of the February 1927 Action Stories! His second printed story—”A Parachutin’ Fool”—was another aviation tale, printed in the April 1927 issue of War Stories! He followed this up with—”Aces Down!”—in the July 1927 issue of War Stories—this was the story that introduced the world to that inseparable trio—The Three Mosquitoes!

His first published story was a taunt tale of aviation and death he titled “Doom’s Pilot” in the pages of the February 1927 Action Stories! His second printed story—”A Parachutin’ Fool”—was another aviation tale, printed in the April 1927 issue of War Stories! He followed this up with—”Aces Down!”—in the July 1927 issue of War Stories—this was the story that introduced the world to that inseparable trio—The Three Mosquitoes! off the ground with an early Mosquitoes tale from the pages of the August 19th, 1927 issue of War Stories. A new C.O. has been assigned to the squadron and he can’t stand pilots who “grand-stand” which is the Mosquitoes stock-in-trade and boy do they catch hell when they get on the C.O.’s wrong side—that is until the C.O. gets in a jam and it’s trick flying that’ll save him when the Boche come “Down from the Clouds!”

off the ground with an early Mosquitoes tale from the pages of the August 19th, 1927 issue of War Stories. A new C.O. has been assigned to the squadron and he can’t stand pilots who “grand-stand” which is the Mosquitoes stock-in-trade and boy do they catch hell when they get on the C.O.’s wrong side—that is until the C.O. gets in a jam and it’s trick flying that’ll save him when the Boche come “Down from the Clouds!” Mosquitoes—the unseasonably warm weather has brought the Mosquitoes out of hibernation to help get through the cold winter months, at Age of Aces dot net it’s our third annualMosquito Month! We’ll be featuring that wiley trio in three early tales from the Western Front. This week we have their third tale—the classic “Devil in the Air” in which Kirby is determined to take on the Boche’s new Fokker all by himself to prove it can be done only to realize there’s no beating the Inseparable trio!

Mosquitoes—the unseasonably warm weather has brought the Mosquitoes out of hibernation to help get through the cold winter months, at Age of Aces dot net it’s our third annualMosquito Month! We’ll be featuring that wiley trio in three early tales from the Western Front. This week we have their third tale—the classic “Devil in the Air” in which Kirby is determined to take on the Boche’s new Fokker all by himself to prove it can be done only to realize there’s no beating the Inseparable trio!