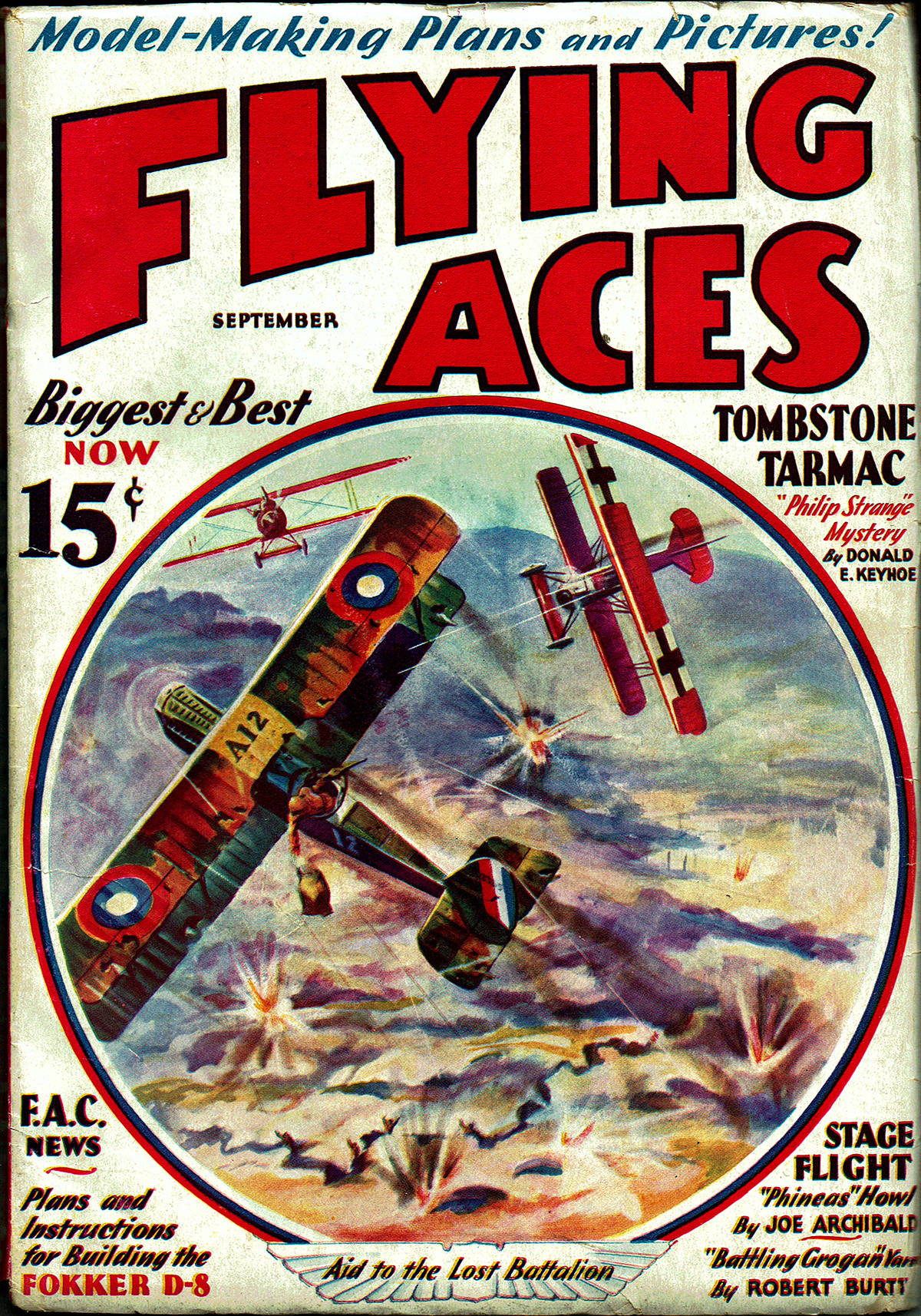

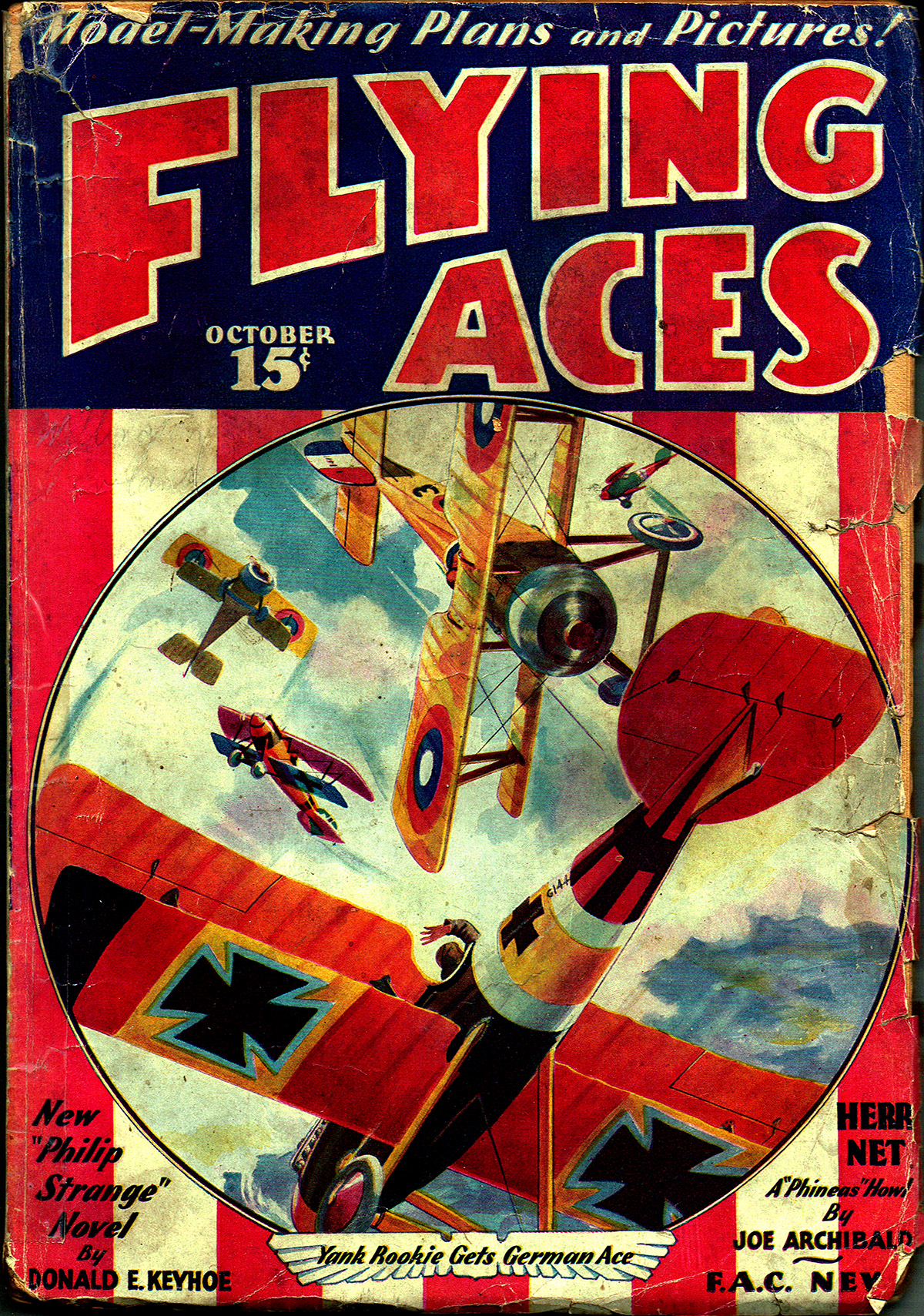

“Yank Rookie Gets German Ace” by Paul Bissell

THIS week we present another of Paul Bissell’s covers for Flying Aces! Bissell is mainly known for doing the covers of Flying Aces from 1931 through 1934 when C.B. Mayshark took over duties. For the October 1933 cover Bissell put us right in the action as a …

Yank Rookie Gets German Ace

IN THE early summer of ’18 the 95th Yank Squadron was having a busy time of it on the Front near Verdun. The long-promised Spads had not yet arrived, and they were still flying their old Nieuports to combat the new Albatrosses and Fokkers with which the Germans were filling the skies.

IN THE early summer of ’18 the 95th Yank Squadron was having a busy time of it on the Front near Verdun. The long-promised Spads had not yet arrived, and they were still flying their old Nieuports to combat the new Albatrosses and Fokkers with which the Germans were filling the skies.

The squadron losses had not been unusual, but quite heavy enough so that replacements were constantly coming up. Often these were lads who had previously been with the French or English, and so had some actual combat experience. But sometimes there would be one who came fresh from the training centers, with only what experience he had received in “aerial combat†at those fields, and not enough of that.

As a general thing, these lads could be broken in gradually, the usual procedure being for the experienced pilots to take them over in formation, avoiding, if possible, a serious scrap, but allowing them to get accustomed to archie and the feel of being out—assisted to be sure, but on their own, where the stakes were life and death.

If a scrap was unavoidable, the new lads were told to stick close in their formation, or if the formation was broken, to pull out of the scrap entirely if the opportunity presented itself. However, things didn’t always work out 15,000 feet up as they were planned on the ground.

So it was with Lieutenant Walter Avery, who came up entirely without experience to join the 95th. He, like all other rookie aviators, without underestimating his job or the danger in it, was impatient to get at the enemy, and restlessly waited for his time to be taken over.

While waiting, he heard tales of the activities of the Boche squadrons in this sector, especially of an ace named Menckeff, who flew a red Albatross with the tips of its lower wings painted black.

This ace had thirty-eight official victories to his credit, and he and his men had been in many a spectacular dogfight with the Allied birdmen of this sector. Possibly at night Avery dreamed of that red ship with the black lower wing tips. Anyway, those markings must have stuck in his memory for—but that’s part of the story of Avery’s big day.

WITH the sun shining down blindingly from the vast blue dome above, seven German ships sped along over the big white clouds below them. High up there, everything was so quiet, so beautiful and peaceful, that it was almost incredible that the veil of smoke seen drifting across the landscape far below was really the shroud of hundreds who at that instant were dying—a sacrifice to the gods of war.

So, indeed, it was impossible to believe that these ships flying swiftly and easily, beautiful in the sunlight, their red wings flashing, were in reality a squadron of death, mercilessly searching for their victims.

Far below, coming from behind a cloud, five tiny specks had appeared, almost invisible against the shell-torn earth still miles beneath them. The quick eyes of the Boche leader had observed them, however, and already his wings were wagging their signal to his comrades. The red, blue and white circles on the lower planes showed them to be Americans. It was the 95th, and Lieutenant Avery was being taken over for the first time.

He had already come through his first tryout with archie, and had marveled at the apparent unconcern of the older pilots when puffs of smoke had appeared all around them as if by magic, and their ships had been bumped around as if by the hand of the magician himself. The flight had shifted course suddenly, and at certain definite intervals, but that was all, and soon the smoke puffs had ceased.

But now it was different. The flight leader had banked up sharply, at the same time giving a quick signal. Avery, looking over his shoulder, saw seemingly countless red ships, their guns blazing, diving straight down on him, and he knew that this was one scrap not as per ground instructions.

Just what happened during the next few moments will always remain a confused mass of memories to the young airman. He tried to remember his warning to stay in formation, but there seemed to be no formation left. He had escaped the first driving onslaught and was now just one of twelve twisting and dodging planes. So far he had not even used his machine gun. There had seemed nothing to shoot at—just flashes of color that passed him before he had opportunity even to determine what they were.

Then some bullets, spattering close to his cockpit, brought him abruptly out of his confusion. His senses cleared. All his training came back suddenly. He threw his ship into a screaming vrille and came out with a red ship square in front of him. Automatically his fingers squeezed the trips, and for the first time he felt the thrill of actual combat. His aim was high. He saw his tracers pass over the top wing of the other ship.

The German was busy on the tail of one of the other Americans and had not noticed Avery. A yank of Avery’s stick brought the whole enemy ship more into line. Then for the first time his eyes caught something that sent his heart into his mouth. The red Albatross had black lower wing tips.

Carefully he sighted, aiming at the nose of the Albatross so that the German would have to pass through the line of fire. Once again his guns throbbed, and this time his aim was true. The German plane shot up in a tight loop like an animal stung unawares, but at the top, his motor sputtered and he dropped off to one side. Right behind him went Avery, his guns blazing, the bullets ripping the sides of the diving Albatross.

It was soon over. They had drifted too far over the Allied lines for the Boche to make the German side; so, with motor gone, unable to fight, and himself wounded, he threw up his hands in surrender. The scrap was over, and Avery headed back for the airdrome.

His squadron mates had seen the newcomer get his German, but it was not until the prisoner had been brought in that Avery was sure his eyes had not deceived him. And not until then did his comrades realize that the young American lieutenant had on his first flight over the lines brought down the famous German ace, Menckoff—a record we believe unique in the annals of the war.

“Yank Rookie Gets German Aceâ€

Flying Aces, October 1933 by Paul J. Bissell