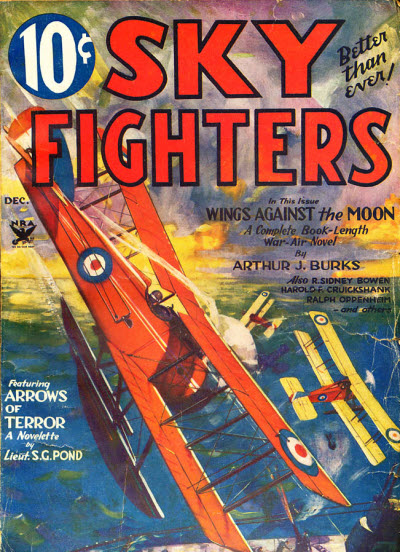

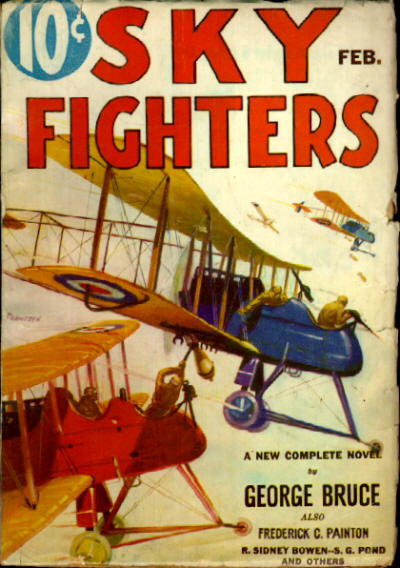

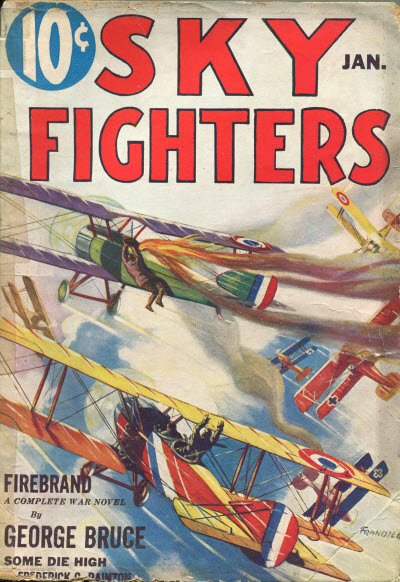

FROM the pages of the March 1933 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

Just How Fast?

by Robert Sidney Bowen (Sky Fighters, March 1933)

WELL, my Fledglings—er, sorry, I should have said Buzzards! Well, anyway, the chin-fest this time is going to be one which I am afraid will shoot a pet belief of yours all to pieces. By the time I get through, you birds will be calling your Uncle Washout all sorts of nasty names, and the main one will be—“liarâ€! But I’ve been called that by dumber buzzards than you (yes, there are a few I think) so don’t build up any hopes of getting my goat. A Sopwith Camel got that, years ago! However, I’m warning you in advance. If you don’t believe me, then get up and walk out. It’s all the same with me. But, if you do stay, keep your traps zippered up until I’ve emphasized the final period and quotation marks.

I’ve been planning to chin this tune to you for some time, but I’ve delayed doing it until we got to know each other a little better. That is, rather, until I got to know you a little better! Well, I’ve found, according to your letters, that your bark is worse than your bite. And so figuring that though you may toss things my way, when I’m through, my one and only life won’t be hanging in the balance.

So, here it comes. Ever read anything like this?

“Slamming the stick over and stepping hard on left rudder, Jim Collins, keen-eyed eagle of Uncle Sam’s brood, spun around on wing-tip and went thundering straight for the Fokker at a speed well over 200 m.p.h. His twin Vickers yammered harshly, and—â€

AND horse collar to you, Jim Collins! And also, horse collar to you, Mr. Author, who lets that sort of stuff drip off your typewriter keys!

You guessed it, Buzzards! I’m going to chin about the speed of all the war flying crates that I and 9,999,999 other dumb peelots made famous. Yeah, I can see that look slipping into your eyes, already. But go ahead—I’m going to chin the truth, the whole truth, so help me!

Jim Collins, or any other pilot during the late mix-up, never went even 200 m.p.h. in level flight. Now when I say, the late mix-up, I’m talking about the World War. Perhaps there’s been another since then, and no one has told me about it. But the World War I mean, is the one that took place between 1914-1918. And during those years no war crate, Yank, British, French, German or Ethiopian, came within 50 miles of a top speed of 200 m.p.h!

All right, all right, sit down! Let’s start right in with the year of 1914 and take a look at the records year by year.

The War, as you all know, and if you don’t, I’m telling you, started in August, 1914. Now up to that date the speed record for land planes was 105 m.p.h., made by Maurice Prevost when he won the Gordon Bennett Cup Race held in France, September 29, 1913. And the speed record for seaplanes was 86.8 m.p.h., made by C. Howard Pixton wrhen he won the Jacques Schneider Maritime Aviation Cup Race (original name of the present Schneider Trophy Contest) held on the Bay of Monaco in March 1913.

Therefore we enter the World War with a top speed of 105 m.p.h. But, don’t overlook the fact that that was the top speed of the fastest racing plane. Not a military ship loaded with guns, ammo, and a bomb or two here and there, but a racing ship stripped of everything possible that would hinder forward progress, and with an engine tuned up for that one race!

Okay, now we turn to the records.

The British sent to the front in the 1914 period, first, the well-known Avro, powered with a Gnome or Le Rhone with a top speed of 65-70 m.p.h. Then there was the B.E. (Bleriot and later the British Experimental) powered with a Renault, that knocked off about 50 m.p.h. Another was the Gnome powered Vickers that slid along at 60-65 m.p.h. And of course the Handley-Page Bomber that had two Rolls-Royce engines, and thundered forward at about 80 m.p.h. Those ships were all two-seaters, or over, and were the vanguard of British ships in France.

Now the French had their good old two-seater Breguet that bent your whiskers back at 55-60 m.p.h. They also had the Bleriot (same as the British) that clicked at around 55 m.p.h. The well-known Caudron that mushed onward at about the same speed. And ditto for the Maurice Farman, the Morane and the early Nieuport. All were two-seaters or bombers save the Bleriot, the Morane and the Nieuport.

AND the Germans? Well, they had the Albatross scout with a Mercedes and. 65-70 m.p.h. to its credit. Then there was the two-seater Aviatik that clicked at around 70-75 m.p.h. And the Taube single-seater monoplane with an Argus engine that could only hit 50 m.p.h. and not go boom!

So taking it all in all the Germans had a general edge of about 5 m.p.h. over the French and British save for the Handley-Page with its twin engine speed of 80 m.p.h. But taking the general top speed average we find it to be around 65 m.p.h. in the first year of the war, or, to be pretty near exact, some 40 m.p.h. below the then existing world’s speed record for all types of aircraft.

Now, in case you think I’m going to go on listing all the various planes year by year, you’re crazy. Such a thing would fill this whole mag. And the C.O. tells me that there are some swell yarns he wants to put in, and for me to go easy on the space. But, I’ve started this fight, and I’m going to finish it by tracing the increase of war plane top speed right through to 1919. I’ll do it by sighting performances of the various leading and famous crates.

Naturally, no World War power made a ship one year, and then tossed it in the ash can for an entirely different design the next. True, that was done in a few cases. But what I’m driving at is that not only were new designs brought out, but the old ones were improved upon. As an example we find the original British Bristol with a Gnome in the nose in 1914 doing around 70 m.p.h., and in 1917 with a Rolls-Royce and a few improvements it did 105 m.p.h.

BUT we’re getting ahead of our chinning. Let’s go back to 1915. That year was really the year that aerial warfare got under way. Prior to then, war flying consisted of reconnaissance and bombing work. But in 1915 the boys got their hands on aerial guns and the works started popping.

The British jacked up the speeds of their old ships a little bit and sent out the first DH single-seater (DH2 Pusher) that could hit 95 m.p.h. That same year the first Sopwith Scout came out with 90 m.p.h. Then there was the first Martinsyde single-seater that made 95 m.p.h. And the fastest of all, the. famous Bristol “Bullet†that did just about 100 m.p.h.

Meanwhile the French got 90 m.p.h. out of a new Nieuport. Some 70 m.p.h. out of a Bleriot scout. And about 5 m.p.h. more out of a new Caudron single-seater. The French seemed to be a bit conservative in their speed figures that year.

That year saw the introduction of the first Fokker. It was called the “Eindecker†and was a single-seater monoplane powered with an Oberursel engine, and had a top speed of 95 m.p.h. The Germans boosted their Albatross speed up to 80 m.p.h. And that was about all they did.

So we see that in the second year of the war England has most of the speed honors. But, believe it or not, the fastest speed is still 5 m.p.h. below the record set in 1913.

However, in 1916, the scrapping nations pulled up their socks and got to work on the idea of shoving their planes through the air at a real good clip.

The British pushed their Avro single-seater up to 100 m.p.h. They came out with a new Bristol that did 105 m.p.h. They made a redesigned Martinsyde do 110 m.p.h. And they sent out the first S.E. an S.E.4 (not S.E.5) that did close to 100 m.p.h. But their greatest achievement was the new DH4 that did around 125 m.p.h. That ship was the fastest of its time.

THE French did a little better by themselves as regards speed in 1916. The most important item was that they came out with the first of the famous Spad pursuit ships. This job, which was powered with a Hispano-Suiza engine, as were all Spads, knocked off 105 m.p.h. The new Caudron twin-engine bomber did 85 m.p.h. which was pretty good for a crate of its size. And the fixed-up Nieuport equaled the top speed of the Spad.

Of course, 1916 was a big year for the Germans. The first Fokker of the famous D series saw front line service that year. Naturally, it was the Dl, and powered with a Mercedes it was good for 105 m.p.h. The Aviatik, with a Benz in the nose had the same speed. And the New Benz-powered Albatross hit the same clip, also. But strange as it may seem, the honey of German ships that year, as far as speed was concerned, was the Benz powered Halberstadt single-seater. The first Halberstadt that year was powered with an Argus and could do 105 m.p.h. But when they stuck a Benz in the nose the ship went up and buzzed along at a nice clip of 120 m.p.h.

And so, at the end of that year we find the British and the Germans pretty much on a par for speed honors, with the French tagging along slightly behind. And not only that, we find that the existing speed record for all types of aircraft has received a good swift kick in the ailerons!

Now, before we step into 1917, let me put a word in for good luck. I have been chinning about the speed of war crates. I have not made any mention of the maneuverability of war crates. So just bear that in mind as we talk on. Speed was an asset, but not the whole thing. So don’t get the idea that just because the French had slower ships that they were doing the poorest job. Far from it, believe you me! In a dog-fight a highly maneuverable ship can trim the pants off a faster ship any day in the week, assuming, of course, that the pilots are equal in skill. So don’t let your grandmother tell you different.

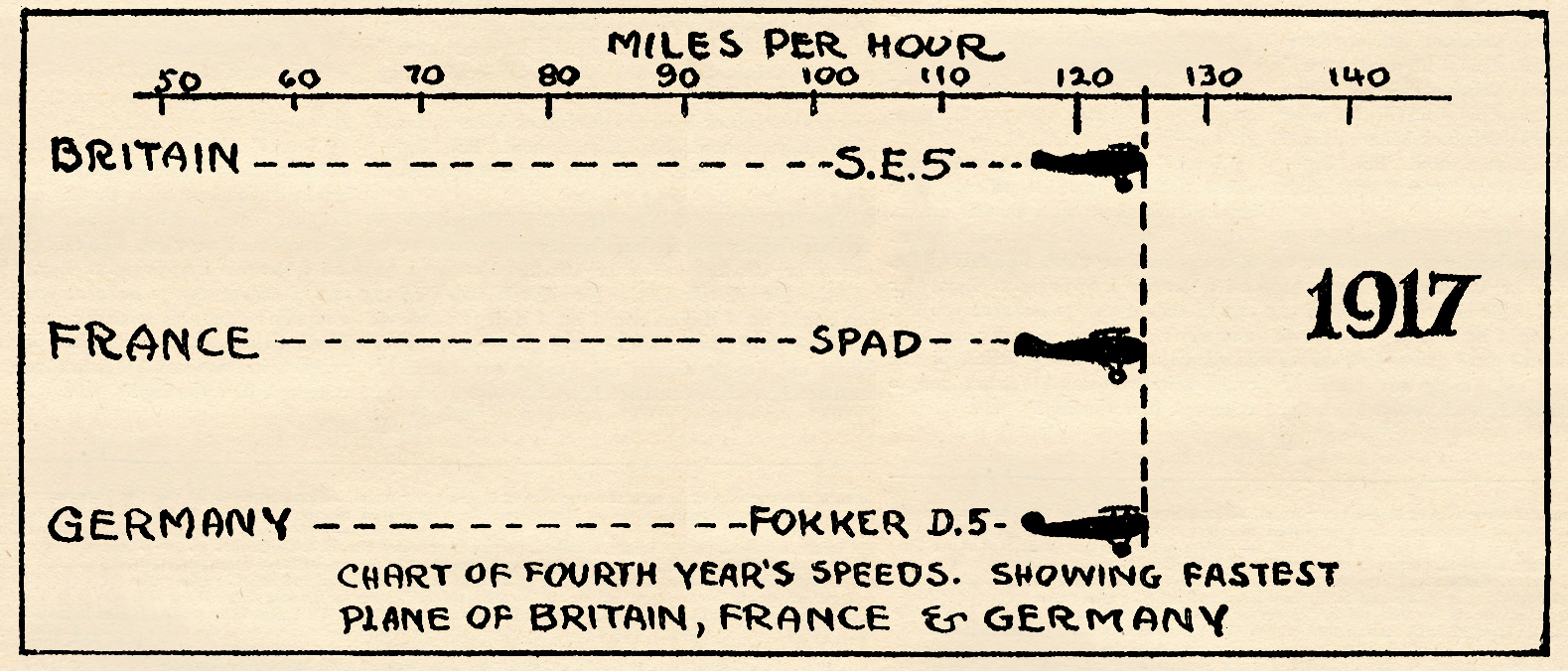

AND so for 1917, the year when supremacy of the air was finally decided for once and for all in the World war.

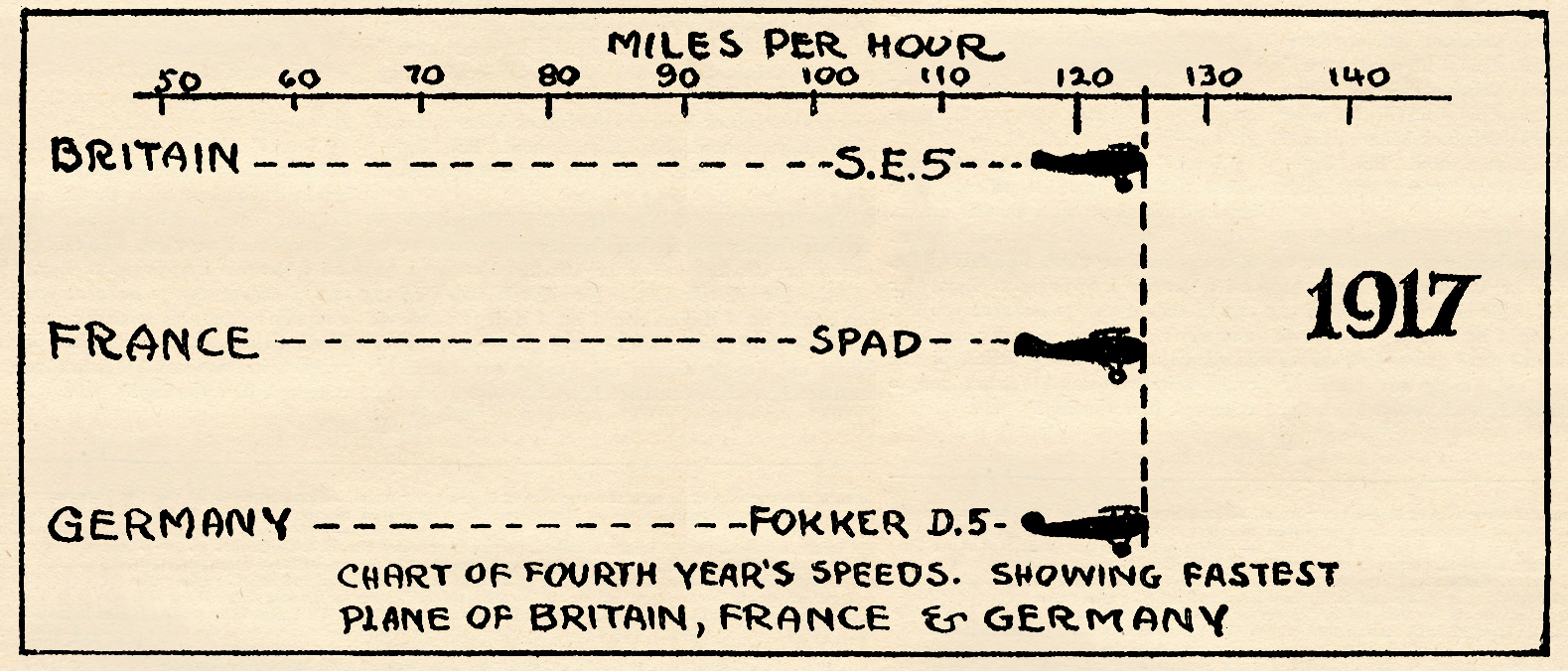

Perhaps the greatest contribution to the art of smacking things out of the sky that year was made by the British when they sent out to France the Famous Bristol Fighter. The job of that year was powered with a 200 hp. Hissi or a 200 hp. Sunbeam, and it slid along, with full load at 120 m.p.h. Next in line was the well-known DH9 with a Napier-Lion engine. This ship, also a two-seater, could do 110 m.p.h. And then came two of the most famous airplanes ever built. First the S.E.5. at 125 m.p.h., and the Sopwith Camel at 120 m.p.h. Both ships were pursuit jobs, as you all know. And—but why chin more? You know all about their history.

To match the British contributions the French brought out a new Nieuport that could do about 120 under full steam with a Gnome in the nose, and about 115 with a Hisso. In addition to that they stuck a 200 hp. Hisso in a redesigned Spad and got a top speed of 125 m.p.h.

Of course the Germans weren’t asleep, either. The first was their new Mercedes-powered Albatross that clicked at 125 m.p.h. The next was the souped-up Aviatik that made the same speed. Then the Fokker D4 at 120 m.p.h. and later the D5 at 125 m.p.h. And last, but not least, the famous Pfalz with a speed of 120.

And so we find England and Germany hitting it off neck and neck, with the edge in favor of England, due to its higher topspeed average for all types. And particularly due to the introduction of two brand new pursuit ships, the S.E.5, and the Sopwith Camel.

All of which brings us up to 1918 and the final showdown.

As usual, England got the jump by bringing out two brand new types, and improving on all the others. The new types were first the Sopwith Dolphin, a high altitude ship that could do 130 m.p.h., and the Sopwith Snipe that could do a shade over 140 m.p.h. with luck. This ship was considered by many to be the fastest thing in France at the end of the war. It came out about three months before the Armistice was signed. The principle improvement on other British designs was that made on the S.E. series. The S.E.5a came out at 135 m.p.h. Then, too, there was the D.H.9a with an American Liberty engine (two-seater) that did 125 m.p.h. And the Bristol Fighter was put up to 130 m.p.h.

The French simply boosted up the speeds of old designs. They got the Spad up to 135. And they got the Nieuport up to around 130. Outside of that, they slammed into the enemy with what they already had.

The Germans worked on the Albatross scout and got 135 m.p.h. out of it. They also came out with the famous Fokker D7, a ship that was credited with 140 m.p.h. as a top speed. And they also came out with the Fokker Triplane with a speed of about 135 m.p.h. The only other ship improved upon was the Pfalz, which was boosted up to 130 m.p.h.

And there, Buzzards, you have the straight dope on the speed of war flying crates. Mark you! I’m speaking of speed at level flight, not diving speed! That was something different. But when you speak of airplane speed, you speak of speed from here to there, not from up there down to here.

AND so—eh, what’s that? I knew it, I knew it! Why didn’t I speak of Yank planes? Well, here’s why, Buzzard, and be surprised if you will. There was not a single American designed and manufactured ship in action in France during the War. True, there was the American Liberty D.H.9a, but that was fundamentally a British De Haviland design. If the war had lasted longer, the American Thomas-Morse might have seen service over Hunland.

One more thing. What was the fastest thing in the air in France? The Sopwith Snipe, you say? Wrong, Buzzard, wrong! It was the tip of a propeller blade. The tip of a nine foot prop at 1800 revs traveled a shade over the nine and one half miles per minute! Figure it out for yourself, or ask Dad, he knows! S’long.

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the