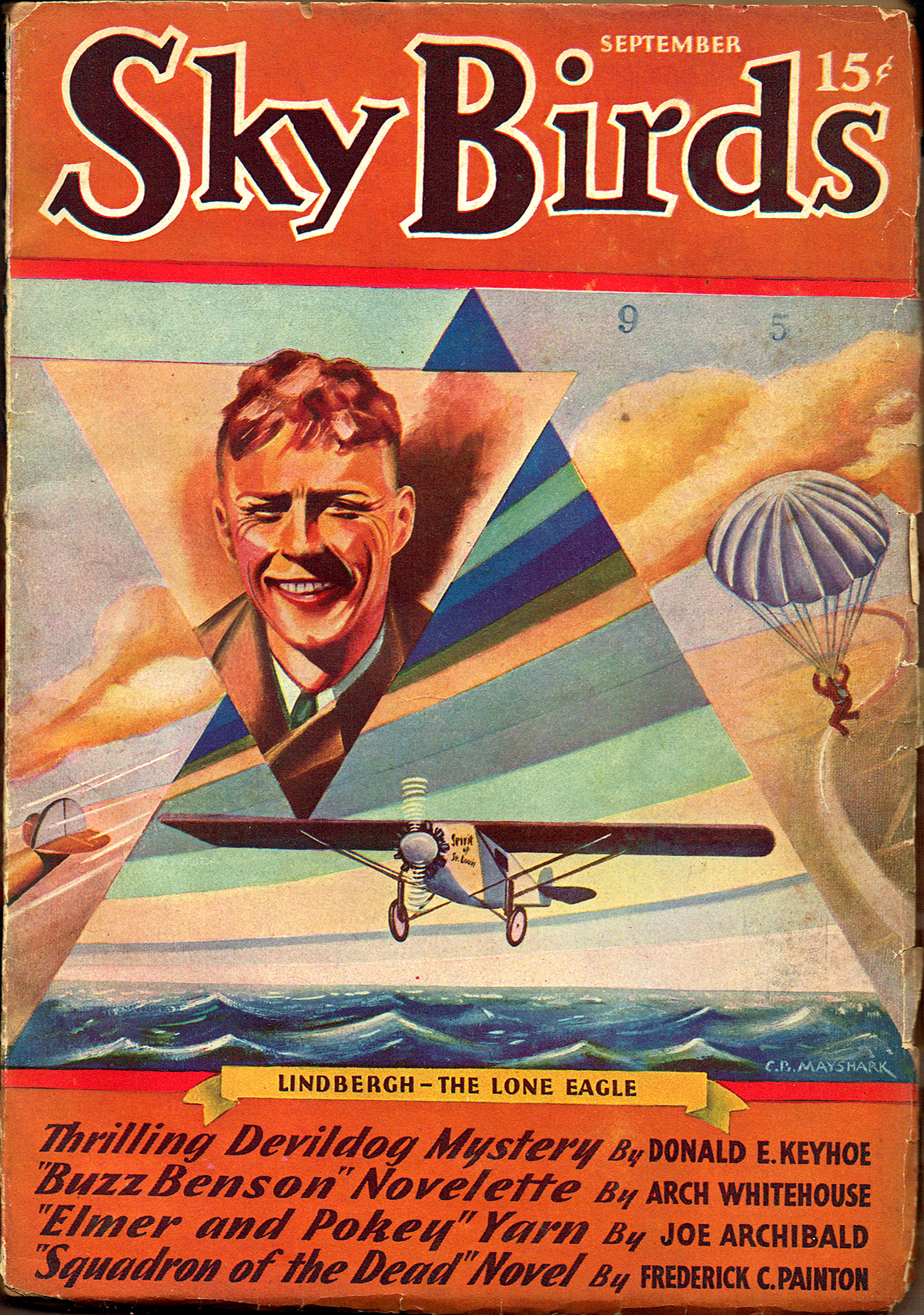

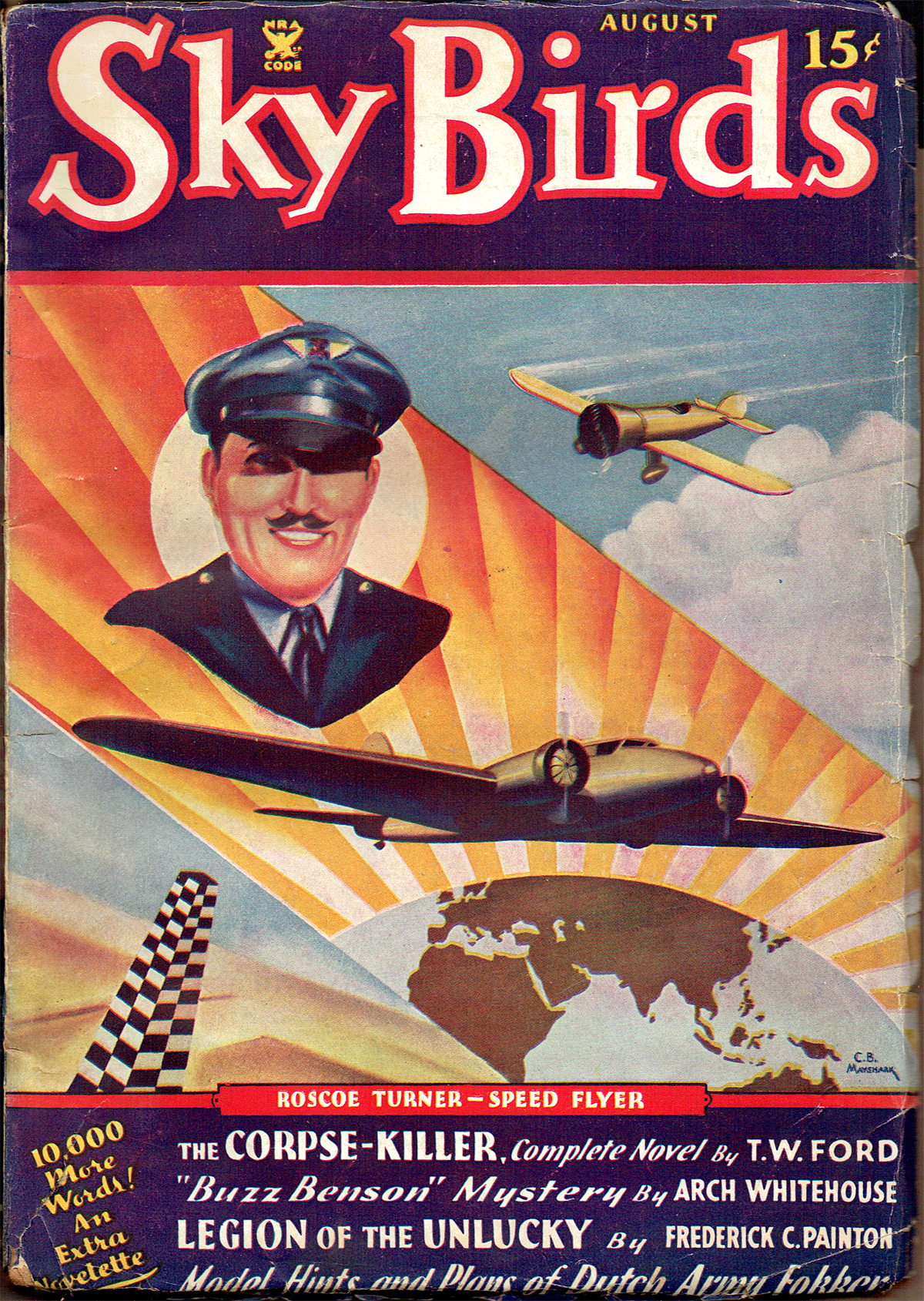

THIS May we are once again celebrating the genius that is C.B. Mayshark! Mayshark took over the covers duties for Sky Birds with the July 1934 and would paint all the remaining covers until it’s last issue in December 1935. At the start of his run, Sky Birds started featuring a different combat maneuver of the war-time pilots. Mayshaerk changed things up for the final four covers. Sky Birds last four covers each featured a different aviation legend. For the first of these covers on the July 1935 issue, Mayshark goes right for the top, featuring America’s greatest Ace of the Great War—Eddie Rickenbacker!

Rickenbacker: Ace in War and Peace

The Story Behind This Month’s Cover

ON THE cover this month, you see Eddie Rickenbacker, one of aviation’s greatest aces—both in war and peace. The premier airman of America’s war-time fighting pilots practically dropped out of sight for twelve years after the World War. He was nothing but a mysterious legendary hero until President Hoover pinned the Congressional Medal of Honor on his civilian coat in 1930, but since then, he has leaped into the aviation spotlight as the new guiding spirit of commercial aviation.

ON THE cover this month, you see Eddie Rickenbacker, one of aviation’s greatest aces—both in war and peace. The premier airman of America’s war-time fighting pilots practically dropped out of sight for twelve years after the World War. He was nothing but a mysterious legendary hero until President Hoover pinned the Congressional Medal of Honor on his civilian coat in 1930, but since then, he has leaped into the aviation spotlight as the new guiding spirit of commercial aviation.

The hand that guided a speeding Spad in 1918 directs the destinies of one of America’s greatest aviation organizations from behind a chairman’s desk and, upon demand, climbs into a 200-mile-an-hour Douglas and pilots it across the United States in twelve hours.

Americans had almost forgotten about Captain Rickenbacker in 1930. They had forgotten about many such heroes of the war days. The first thud of the great depression had left the country reeling, unable to think of anything so romantic as a knight of the air. Minds were on banks, stock markets and ticker tape.

It is significant that the man who came to the aid of his country in 1918 with his skill as an auto driver, his knowledge of engines and, later, with his ability as a pursuit pilot, should be the first to take up the gauntlet again in the defense of commercial aviation.

The depression hit first at the infant industry of air travel. Aeronautical stocks fell, factories had to close up that had been organized during the boom following the surge of interest when a young air mail pilot named Charles A. Lindbergh flew solo from New York to Paris in 1927. Many air lines, enjoying their first profits in a legitimate transportation organization, felt the terrific shock of nationwide poverty. Some went under, others retrenched, and even those backed by plenty of money realized that something had to be done to prevent complete ruin and the wiping out of the gains that had been made in the aeronautical field. They began looking about for a MAN who could be a leader.

There were hundreds of pilots. There were scores of crack pilots. There were a few, a mere handful, who had won world renown for their flights. But none had business instinct along with their skill with tho joy stick.

Then the publicity resulting from the belated award of the Congressional Medal of Honor by President Hoover brought the almost forgotten Captain Eddie Rickenbacker back into the limelight. Here was the MAN for aviation!

The men who directed the financial destinies of our big commercial firms looked up Rickenbacker’s background. A few learned for the first time that he was America’s Ace of Aces. He had destroyed twenty-six enemy planes on the Western Front. They studied his war career and discovered that against the worst possible obstacles, he had climbed out of an easy berth as private chauffeur to General John J. Pershing and had worked his way up to be a flight commander in the top-ranking fighter squadron of the A.E.F.

They discovered that in this long climb, Rickenbacker had once been waylaid at a motor repair depot because of his knowledge of engines, and it looked as if he would have to stay there. But “Rick” proved that he was not indispensable by faking an illness and getting himself placed in hospital for two weeks. When he came out, he said, “You see, I’ve been away from the depot for fourteen days. During that time, things went on just as though I had been there. Now, why can’t I go up to the Front and fight?”

There was no argument to that, so Eddie went up to the Front.

Next, these financial wizards discovered that, once up at the Front, Rickenbacker did not go mad and try to win the war on his own. He took his time and studied the problems before him. He flew his daily patrols and developed his technique. He finally went into action—but after he had his battle plans laid hours before he left the ground.

He studied enemy ships in the air and checked captured ships for their blind spots and weaknesses. He was pretty colorless at first, but he plugged away, and before anyone knew just who this quiet, methodical young man was, he was top pilot of the A.E.F.—and he lived to come home to his reward.

“This is our man,” the aviation magnates said. “He’s the one to save commercial aviation. Let’s get him.”

They had a hard time finding Rickenbacker at first, for he had a very ordinary routine job with the old Fokker Aircraft Company, acting as a salesman for the ships of the man whose war-time products had given him so much trouble. Eddie also eked out his meager pay by writing sane and sound articles in a few of the aviation magazines. But the general public did not read those magazines in those days. They were still buying thrills, world flights, refuelling stunts and mad Roman Holiday air races that featured crazy acrobatics and lengthy death rolls.

They took him out of there when Fokker packed up and went back to Holland. They sent him to the General Aviation Corporation, the General Motors aviation branch, and let him go to work. For months, nothing much was heard of Rickenbacker, but he was working hard, building up a new and solid foundation for America’s commercial air program.

Gradually, Rickenbacker’s work began to tell, and he appeared in the headlines again. There was a sure climb in air line patronage, and demands came for faster and more comfortable ships. The big companies went to work and, with keen competition driving them on, they soon began to revolutionize the air liner. There were the new Boeings and the Vultees. Then came the Lockheeds, Stinsons and G.A. ships. But soon all these were to be outclassed by the Douglas that had a top speed of 234 m.p.h. With its showing in the great London-to-Melbourne race last year, when it finished second only to an out-and-out racing plane, America finally learned that it had the finest air transportation system in the world.

But there was one point to be cleared up, and this is where Captain Eddie Rickenbacker came in. America knew the Douglas had done well in the England-to-Australia flight, but then it had been flown by a team of Dutch pilots who knew that route like the lines in the palms of their hands. How would it fare in the hands of an American crew over the complete route from coast to coast in this country?

The air lines were asking this. The prospective passengers were asking this. The operators were asking the same question.

Rickenbacker, the Man, answered them.

On November 8th, 1934, a few weeks after the great Melbourne race, he directed the flight of a twin-motored Douglas from Los Angeles to New York in the commercial record time of twelve hours and four minutes. Again, he flew it from New York to New Orleans in record time, and he completed a round trip from New York to Miami within the limitations of breakfast and supper time.

America was satisfied. Rickenbacker, the Man, had showed them, just as he had showed them with his Hat-in-the-Ring Squadron in 1918. Within twenty-four hours of his record flight across the country, the air line offices were swamped with reservations for the Douglas-equipped lines all over the country.

But it will not end there. Rickenbacker is still at work, planning and plotting for the future. His pilots will get most of the credit, but commercial aviation will go on, a glorious monument to the man who quietly tackles his problems without benefit of publicity. Rickenbacker, the MAN—the ace of war and peace!

“Rickenbacker: Ace in War and Peace” by C.B. Mayshark

Sky Birds, July 1935

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

exciting air adventure with Rusty Wade from the pen of Frank Richardson Pierce. Pierce is probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

exciting air adventure with Rusty Wade from the pen of Frank Richardson Pierce. Pierce is probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

Silent Orth had made an enviable record, in the face of one of the worst beginnings—a beginning which had been so filled with boasting that his wingmates hadn’t been able to stand it. But Orth hadn’t thought of all his talk as boasting, because he had invariably made good on it. However, someone had brought home to him the fact that brave, efficient men were usually modest and really silent, and he had shut his mouth like a trap from that moment on.

Silent Orth had made an enviable record, in the face of one of the worst beginnings—a beginning which had been so filled with boasting that his wingmates hadn’t been able to stand it. But Orth hadn’t thought of all his talk as boasting, because he had invariably made good on it. However, someone had brought home to him the fact that brave, efficient men were usually modest and really silent, and he had shut his mouth like a trap from that moment on.

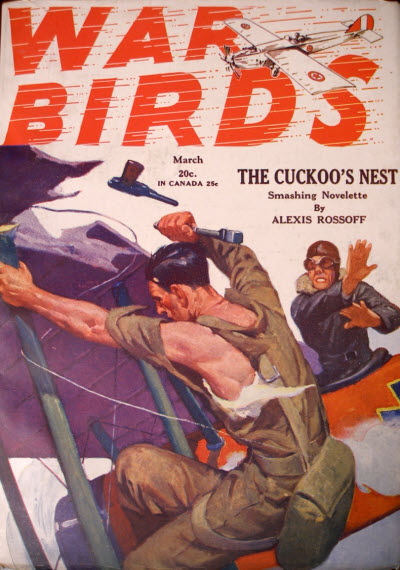

tale from the prolific pen of Alexis Rossoff. Rossoff started out in the ’20’s writing air and war fiction for the various magazines. By the mid-30’s he had shifted his focus away from tales of WWI intrigue to sports stories. Here we have the first of his Cuckoo’s Nest stories that ran in War Birds in 1930. The Cuckoo’s are an outfit a lot like Keyhoe’s

tale from the prolific pen of Alexis Rossoff. Rossoff started out in the ’20’s writing air and war fiction for the various magazines. By the mid-30’s he had shifted his focus away from tales of WWI intrigue to sports stories. Here we have the first of his Cuckoo’s Nest stories that ran in War Birds in 1930. The Cuckoo’s are an outfit a lot like Keyhoe’s

a story from the pen of A. Kinney Griffith. Griffith penned a number of stories featuring Rex “Wrecks” Norcross that ran in the pages of War Birds and Sky Riders in the late ’20’s. He gained his nickname by crashing his first time back from patrol in a shot-up plane that was barely holding itself together, but as time went on he returned as less of a wreck, while wrecking the German planes!

a story from the pen of A. Kinney Griffith. Griffith penned a number of stories featuring Rex “Wrecks” Norcross that ran in the pages of War Birds and Sky Riders in the late ’20’s. He gained his nickname by crashing his first time back from patrol in a shot-up plane that was barely holding itself together, but as time went on he returned as less of a wreck, while wrecking the German planes!