How the War Crates Flew: Konking Engines

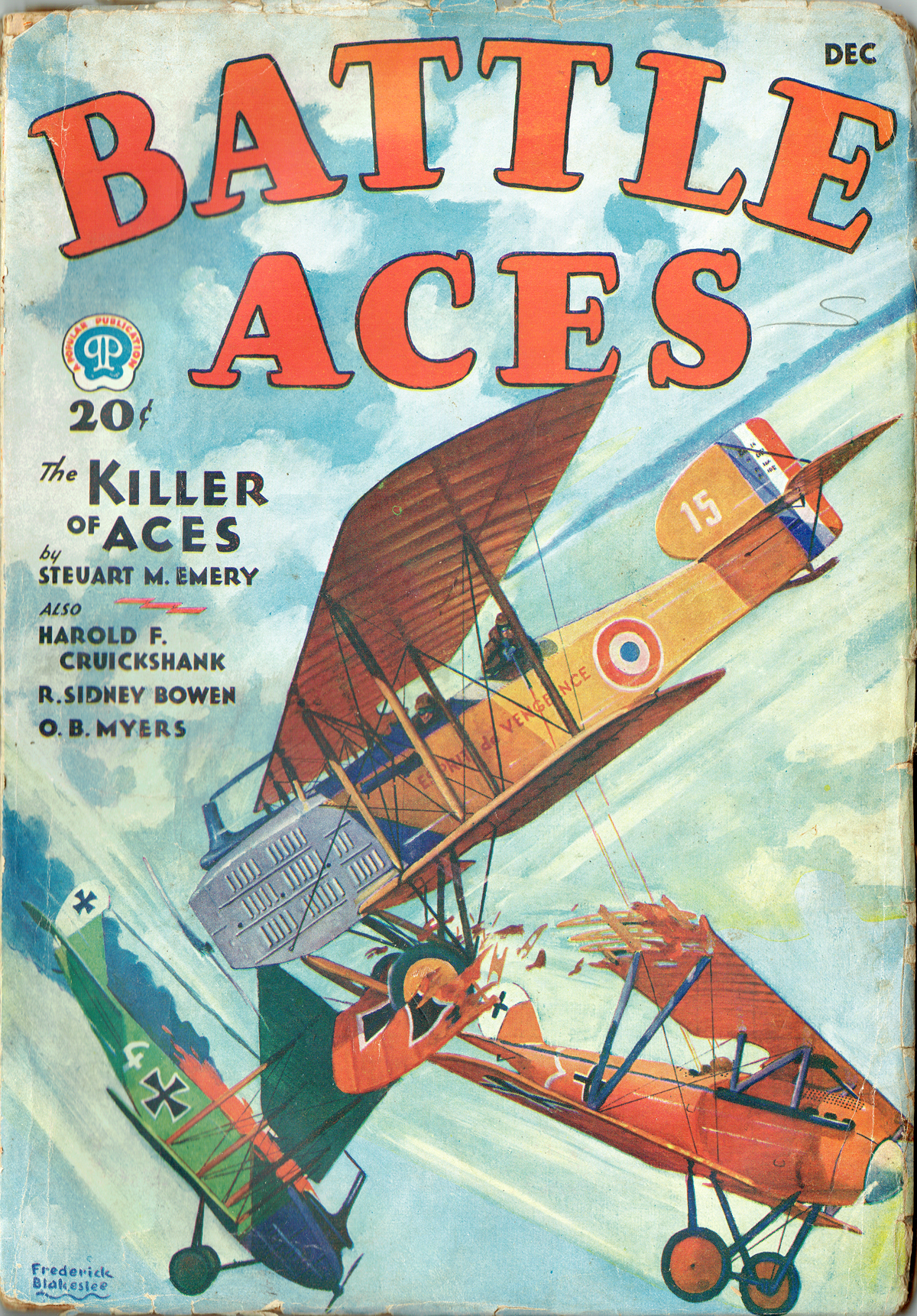

FROM the pages of the November 1932 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

Konking Engines

by Robert Sidney Bowen (Sky Fighters, December 1932)

ALRIGHT, YOU FLEDGLINGS, sit up and pay attention! – Huh? What am I sore about? Well, I’m not exactly sore, just a little bit nettled, if you get what I mean. Its this way. A flatspinning fledgling out Arkansas way (I won’t mention his name) has sent me a letter that calls for a light in any country. Yup, its little short of an insult to all us wonderful war pilots.

He says in part:

I have been reading air magazines for a long time, and although I enjoy the stories, particularly Air Fighters yarns, there is one thing that gives me a pain in the neck. Why, does the Hero always have his engine go blooey just when he’s all set to knock some Fokker out of the sky?

Did you war pilots ever inspect your engines, or were you just too darn lazy? In other words, there were too many forced landings in the World War to suit me. I’ll bet I’d have kept the old crate going, if I had been over there!

Now I ask you, is that conceit, or is that conceit? However, in view of the fact that some of you other babes-in-wings have hinted at the same thing, I’m going to devote this meeting to konked engines, and how they got that way. If I get too technical, its just too bad for you. So button back your ears!

Before I start, though, I’ll stick in a word about forced landings in general. No pilot ever asked or prayed for one! And we’ve all had them. Right from me, the greatest, down to you, the poorest. A few years ago the papers were full of news about H.M. Prince of Wales falling off his horse. People began to get the idea that the Prince did not know how to ride, which was certainly the wrong idea. Mr. Will Rogers cleared that point up when he asked, “What’s the Prince going to do when his horse stumbles and falls, stay up there?†Well, that also goes for pilots with konked engines. What are they going to do? Walk around on the clouds while the ship glides down?

But to get real serious. Many forced landings during the late war were due to carelessness on the part of the pilot. But an equal number were just tough luck. We’ll pass over the carelessness part and just deal with the tough luck. In short, what were the things that made the old power plant give up?

All the answers to that would fill up this whole magazine a couple of times. So we’ll just deal with the major causes. Like in an automobile engine there are three important things in an airplane engine. The oiling system, the carburation system and the ignition system. All three are absolutely indispensable to the proper functioning of the engine, and the failure of any one of them will cause the other two to fold up.

Take the carburation system. The gas used during the war was usually the best that could be turned out. It was high test, AA, No.1, etc. But, the facilities for storing it at the squadron, often were not of the best. Careful as the pilot and mechanics might be, a few drops of water sometimes got into the gas tank. Eventually those drops of water got into the carburetor. Water being heavier than gas, they collected around the base of the needle valve and prevented gas from being sucked through into the cylinder head. Naturally, the engine stopped because it was gas starved.

Sometimes those drops of water didn’t get as far as the carburetor. They got stuck in a bend in the feed line—a bend that went upwards. The result was that the carburetor was blocked off from gas.

IN EITHER case, the line and the carburetor had to be blown free of water before the engine would hit on all six, or twelve. Now I’ll admit that sometimes the suction of your engine was great enough to suck the water clear, but lots of times it wasn’t. So you’d have to land and clear out the line on the ground.

And another thing. Air engines during the war, were comparatively speaking, mighty delicate pieces of machinery. Just let a few specks of dirt get in with the gas (all gas was strained into the tank as a precaution against that) and sure as the Lord made little apples, those specks of dirt would find their way into the carburetor and gum up the works. Most times they’d get under the needle valve seat, and keep it open, with the result that the carburetor would flood, and your engine would be gassed to death.

And one more thing about gas and carburetors. Vibration from violent maneuvering, to get the heck away from that Hun, would shake loose some of the feed line joints. The next thing you knew the raw gas would be spilling out into God’s open spaces, instead of into the carburetor. And I’m not even saying a word about a Spandaus bullet nicking a feed line, or puncturing your gas tank.

Now, take the oiling system. Most air engines during the war were oiled by what was known as the splash system. Your engine of today is oiled by force feed, or a combination of splash and force feed. In the war engines the big end bearing of the piston slapped down into a sump full of oil and splashed oil all over the place. Oil reached the parts missed by the splash by working its way by centrifugal force through hollowed out channels. Of course, with force feed, you have an oil pump working off the cam shaft, that pumps oil to all necessary parts of the engine. However, with the war engines the oiling system was often put on the blink just the way the gas system was. In other words, some dirt would lodge itself in one of those hollowed out channels, block off an important bearing, and cause said bearing to burn out, due to lack of lubrication. And it did not have to be actual dirt either. A little gob of crusted grease would do the trick. True, engine failure, due to the failing of the oiling system was not particularly common. At least not in my experience. However, it did happen. And nine times out of ten, all the care in the world would not have prevented it.

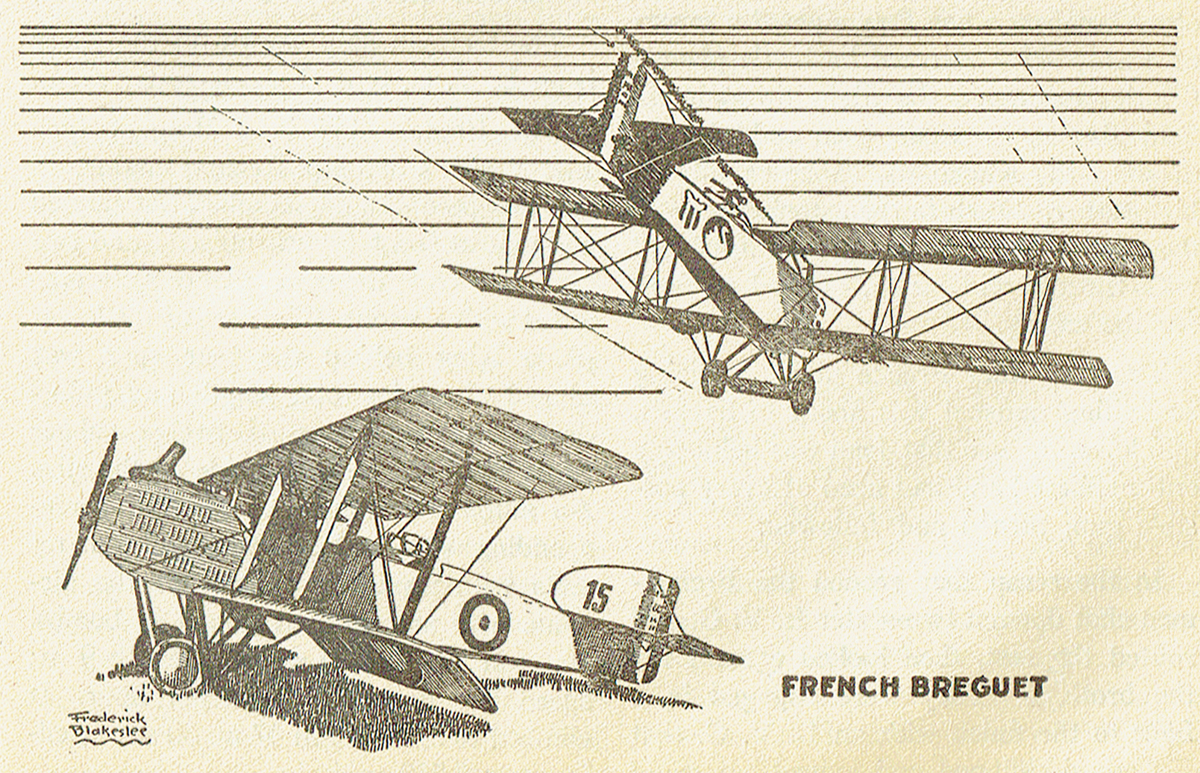

There’s one thing you fledglings sometimes forget. That is, that the war crates were built and flown eighteen to twenty years ago. In other words, the ships you toot around today, have incorporated in them almost twenty years of aeronautical progress.

Now don’t get me wrong. As I said at another meeting, I’m not trying to give you the impression that we war pilots were supermen, etc. I’m just trying to bring to light a few of the things we bucked up against when you fledglings were doing flat spins in your cribs.

AND now for some words about the ignition system. Believe it or not, eighty per cent of the troubles that happen to your automobile are due to the ignition. If you doubt that, ask the first automotive ignition specialist you meet. The same thing held true with air engines. In your car you have battery ignition. In the war crates you had magneto ignition. Of course you have to interrupt me, and ask why? Well, a battery is additional weight for one thing. And for another, there was no ignition battery during the war that could stand being tipped upside down without the electrolite (liquid content of a wet battery) spilling out.

Yes, I know, I know! There were dry batteries to be sure, and planes that had wireless sending sets used them. But, you cannot recharge a dry cell. And that would call for new batteries darn near every patrol. And that would be too expensive for any government, even though said government had decided not to pay their war debts!

NOW I could get so technical that you’d go ground looping, but I’ll spare you, and just deal with ignition troubles in general. The first, and a very common one—spark plugs quitting. In most cases it was due to the plugs getting carboned up. The gas used in war crates was, as I have told you, very high test. In other words, it ignited, and how! Now, if the rings in the piston are not so good, and the oil ring fails to wipe the cylinder walls clear of all excess oil on the downward stroke, that oil is going to be burned when the vaporized gas is ignited. The result, of course, is carbon that collects on the spark plug points. Presently the gap between the points is closed up with carbon and the plug stops firing. Of course one plug going out does not necessarily mean a forced landing. But it means a loss of maximum power and a ragged engine. I once had the actual experience of getting back home with three plugs quitting on me. But that was in a rotary engine, and the inertia of the revolving cylinders aided by the six other firing plugs (a 9-cylinder Bentely engine) enabled me to make the grade, thank goodness! However, in a stationary engine, more than one plug quitting means that you’ll have a forced landing, nine times out of ten.

Of course the major part of an ignition system is made up of wires. Each wire, naturally has a definite purpose, else it wouldn’t be used. Therefore, if any one of them gets loose, it stands to reason that something is going to happen And something does. Any spark plug wires that shake loose and hit against the engine block instantly short circuit the cylinder for which they were intended. And let the engine ground wire work loose and the whole system goes on the blink. Now, when I say ground wire, I don’t mean a wire leading to the ground, terra-firma in other words. All ignition systems have a definite course of travel for that invisible thing called electricity. In your car it starts from the battery and goes right through your engine and back to the battery again. The path of return is called the “Ground.” In other words it has got to get back where it started. The part of it that is spent is made up for by the generator. To be more definite, the current starts from the battery, is maintained by the generator which also shoots it back to recharge the battery again. In the airplane engine of the war days, the magneto functioned as the battery, and generator combined. It still does in a lot of today’s ships. If wet batteries are used they are used mostly for lighting in the cabin, etc. After all, a battery is added weight, and a magneto gives a hotter spark, so naturally, everything is in favor of magneto ignition in airplane engines, instead of battery ignition.

Now, of course, one could say that constant inspection of your engine and its various parts would go a long ways toward preventing any of the faults of which I have been talking, coming to pass. And to a certain extent, that is true. And it is also true that we inspected our ships before each patrol until we were blue in the face. But in those days all the little kinks had not been ironed out of engines, and their construction was not of the best, so things did happen. I don’t mean to say that we had forced landings every time we took off. Far from it. But we did have plenty. Some of us, more than our share, perhaps. But we never prayed for them, and we did everything possible to prevent them. However, Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither was a perfect aero engine. Our experiences during the war were ground work for engineers to work upon. So the next time your hero gets a konked engine just as he’s going to blast that Fokker apart, just bear in mind that he hasn’t got a 1932 aero engine up there in the nose. Either that, or else the author forces the poor bird down so that he can be taken prisoner and later escapes with valuable information swiped right off the Kaiser’s desktop.

But anyway, keep on writing in your questions fledglings, because, after all, I don’t get really and truly nettled when you take cracks at us broken-down eagles who used to make three-point landings . . . upside down! Cheese it! . . . The C.O. of this magazine!

Canada’s very own

Canada’s very own  pen of the Navy’s own

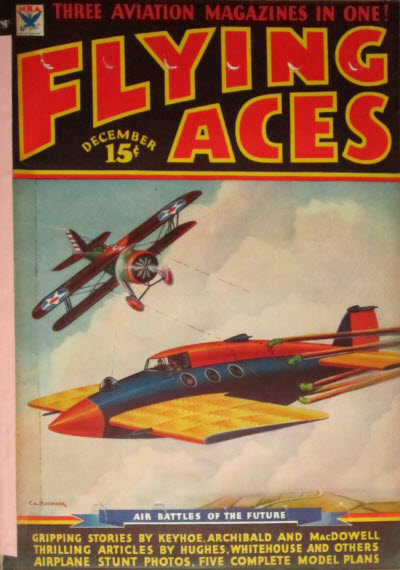

pen of the Navy’s own  issue of Flying Aces and running almost 4 years,

issue of Flying Aces and running almost 4 years,

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!