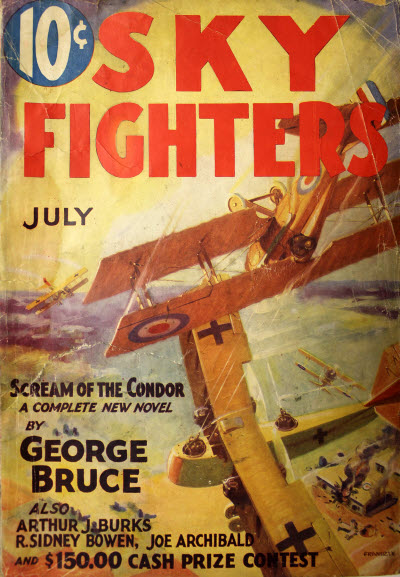

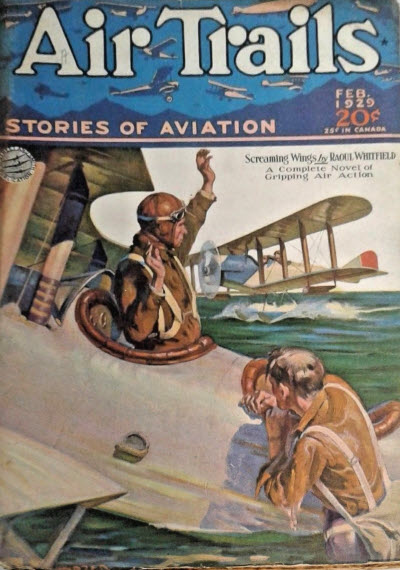

FROM the pages of the July 1932 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

The Constaninesco Interrupter Gear

by Robert Sidney Bowen (Sky Fighters, July 1932)

ALEC WATSON, leading Hun getter of the 23rd Pursuits, crouched over the stick, glued his eye to the ring-sight, and tripped the triggers. . . .

Now just a second, Alec old sky eagle! What do you mean, tripped the triggers? Generally speaking, that is correct. But technically speaking it is not so correct. You, personally, Alec, do not trip the triggers. Of course, being an A1 Hun getter, you realize that. But there are a lot of fledglings around here who don’t. So I think it would be a pretty good idea if we went into this question of tripping triggers, and found out just what it was all about.

Alright, fledglings, gather ’round, and let’s go!

The pilot of any pursuit plane used in the great war, could only shoot in one direction . . . that was forward. Sometimes he had one Vickers gun mounted on the engine cowling, and one Lewis mounted on the top center section. Sometimes he had two Vickers and one Lewis. And sometimes he had just two Vickers. But regardless of what he had in the way of guns, they were always mounted on something and pointing straight forward. We’ll just forget about the Lewis gun because that was mounted on the top center section and therefore was able to fire clear of the top peak of the propeller disc. Now when I say propeller disc I simply mean the circle inscribed by the revolving propeller.

But, the Vickers gun being mounted on the engine cowling, just forward of the pilot’s cockpit, must fire through the prop disc, if it’s going to fire at all.

I just heard some one ask: “What about hitting the revolving propeller blades?â€

Well, fledgling, that’s just what I’m getting at. We don’t want to hit the prop blades, do we? I’ll say we don’t! So some way we’ve got to work things so that the shots from our gun will pass between the prop blades on their way to that Hun johnnie sitting up there in the sky.

And here is how we do that little thing.

As a matter of fact, it has already been done for us. A gentleman by the name of Constaninesco invented what was known as the Constaninesco Interrupter Gear. It was composed of four parts. 1. The generator. 2. The trigger motor. 3. The reservoir with Bowden control. 4. Pipe lines, main and secondary.

The generator is simply a small* cylinder affair with plunger attached, which is mounted forward on the engine, and in a vertical position. The drive for the generator is generally taken (on stationary engines) from the boss of the propeller by means of gears which engage with a cam shaft leading to the vertical generator. To put it another way, the generator is just a small cylinder with a plunger at the top which is forced down every time the revolving cam on the cam shaft strikes it. And that cam shaft is not the cam shaft of the engine itself, but a separate cam shaft which is revolved by means of gears which attach it to the boss of the propeller. And, of course, when I say boss, I mean the metal plates and bolts which hold the propeller on the crankshaft of the engine.

Now, the next thing is the trigger motor, as it was called. As you all probably know, the Vickers gun operates (briefly) by, what is cabled, the lock moving forward and backward inside the gun. The lock is about three inches by four inches and maybe an inch or so thick, and contains all the trigger mechanism of the gun. Now, one of its actions as it moves forward in the gun is to cock the trigger which is a part of it. Then as it rides back again in the gun the trigger, which projects up out of the top a bit hits against a movable pin fitted at the rear of the gun casing. And of course that action trips the trigger and the gun fires.

IT IS that movable pin that I’m yarning about now. It is simply a round slender piece of metal which projects out of the rear end of the gun and is fastened to a thumb lever. In other words, when firing a Vickers on the ground you simply grip the spade handles of the gun and press your thumbs against the thumb levers. That forces the pin forward so that the end of it trips the trigger as the lock slides back. Now, when you don’t press the gun naturally doesn’t fire because the pin, which is really like a plunger on a spring, is forced back by the spring action so that the trigger doesn’t touch it as the lock slides back.

Now, what we’ve got to do is attach something to the rear end of that pin to take the place of the thumb levers. The reason being, that running from our generator up front to the pin at the rear of the gun is a length of quarter inch copper tubing which is filled with oil. Ah, you’re guessing it already. That’s right . . . as the cam rotates and strikes the plunger in the generator it sends a pulsation back along the copper pipe full of oil and forces forward the pin in the rear of the gun so that it trips the trigger of the lock. So what we really do is fit another plunger to the rear of the gun to take the place of the pin with its thumb levers.

Now, so far, we have a plunger at the forward end of the copper tubing, and another plunger at the rear end. The forward plunger is set so that the revolving cam will hit it. And the rear plunger is set so that as a pulsation of oil forces it forward it will trip the trigger lock.

Just oil (nine parts parafine and one part BB vacuum oil in the copper tubing isn’t going to do us any good unless we put that oil under pressure. So we use what is called the reservoir. The reservoir is something like a double bicycle pump. In other words, a plunger and chamber inside of a larger chamber. At the end of the inner chamber there is a copper pipe-line running to the one we’ve just been talking about. Just so we won’t get too mixed up, the copper tube running from the generator to the trigger motor is called the main pipe-line. And the tube running from the reservoir to the main pipe-line is called the secondary pipeline.

Now, the plunger in the inner chamber of the reservoir is attached to a handle at the top, and there is a strong spring around the stem of the plunger to keep it forced down. In other words, when the handle of the plunger is pulled up and released the spring tries to force it down. And of course the reservoir is attached to the inner right side of the cockpit, at an angle of forty-five degrees, so that the pilot can grab it when he wants to put the oil under pressure.

So now let’s see just how we work the thing.

OF COURSE we assume that there is oil in the main pipe-line, in the secondary pipe-line and in the outer chamber (low pressure chamber) of the reservoir. There isn’t oil in the center chamber (high pressure) because the plunger is down at the bottom. But all of this oil is under atmospheric pressure. In other words, not enough pressure to force the generator plunger up so that the revolving cam will strike it.

Okay, let’s go. We pull up the handle of the reservoir. In doing that we suck oil from the low pressure chamber into the high pressure chamber. Then we let go the handle and the spring tries to force the plunger down, and that action puts the oil under a pressure of 150 lbs. per square inch. Now the oil in the high pressure chamber and the oil in the secondary pipe-line is under pressure. The oil in the main pipe-line is not, because where the two pipe-lines join is a three-way valve. To get pressure in the main pipe-line we have got to open that three-way valve.

We do it this way. From the joy stick to that valve is a movable wire in a metal casing. (Something like the choke wire on your car.) On the joy stick that wire, called the Bowden control, is attached to a clamp you can press. Oftentimes it is attached to a thumb lever you push forward. But squeezing the clamp, or pushing the thumb lever, pulls the Bowden control wire and opens the three-way valve. Of course then the oil in the main line is put under pressure. And in being under pressure the plunger in the generator is forced up so that the revolving cam will strike it.

Alright, the cam strikes the plunger and forces it down. A pulsation, traveling at the rate of 4,000 ft. per second, starts back along the main pipeline. It reaches the point where the main pipe-line is joined to the secondary line. But because of the three-way valve it can’t shoot up the secondary line and hit against the reservoir plunger. So it carries right on along the main pipe-line and hits against the plunger in the trigger motor, and of course shoves it forward. And when the trigger motor plunger is forced forward, it of course trips the trigger of the lock and the gun is fired. Now, that pulsation after it has hit the trigger motor plunger naturally wants to bounce back along the main pipe-line. But we stop that by putting a check valve in the trigger motor. Then, of course, the pulsation can’t bounce back and interfere with pulsation coming forward.

We have yarned about this step by step. But of course you understand that these pulsations are traveling at the rate of 4,000 ft. per second, and things happen fast. And whenever the lock slides back again with its trigger cocked there are always pulsations to slap the trigger motor plunger forward and trip the trigger again.

IN CASE you’ve forgotten, all this is happening because we are still pressing the Bowden controls. Once we let go, the three-way valve closes and the main pipe-line goes back to ordinary pressure and the generator plunger sinks down where the revolving cam doesn’t hit it. To fire again we simply press the Bowden control and that opens the valve again. The 150 lbs. per square inch pressure is maintained for about ten bursts of any length. And then we have to pull up the handle again and renew the pressure. In order to get it clear in your minds about those pulsations, the oil being under pressure, a single pulsation is like a solid rod moving through the main pipe-line. And the number of pulsations is determined on how the cam shaft is geared to the prop boss. In other words, according to the speed of the revolving cam shaft.

And there you are.

No, we’re not. That young fledgling is checking on me again. “How about hitting the prop blades?†he asks.

Alright, it’s like this. The cam is set so that it strikes the generator plunger when the trailing edge of the prop blade (two-bladed prop) is one inch past the bore of the gun. In the case of a four-bladed prop the cam should be set when the center of the blade is right opposite the bore of the gun. That is, of course, assuming that the muzzle of the gun is four feet from the revolving prop blades. The nearer the gun is to the prop the nearer you set the cam to the trailing edge.

The Editor of this mag of yours has just looked over my shoulder and reminded me that I’m not writing a book, so I’d better quit.

And so, you fledglings, when these leading Hun getters trip triggers again, don’t let ’em kid you. They are just pressing the old Bowden control to open that three-way valve to put the main pipe-line under pressure so that the oil pulsation will trip the triggers. Can you beat it? . . . These sky birds are just a bunch of oil pumpers!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

a story from the pen of British Ace,

a story from the pen of British Ace,  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

exciting air adventure with Rusty Wade from the pen of Frank Richardson Pierce. Pierce is probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

exciting air adventure with Rusty Wade from the pen of Frank Richardson Pierce. Pierce is probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.  winter days with snow streaking through the sky, it seems right and proper to introduce Frank Richardson Pierce to you folks. Pierce lives up in the Northwest, up in Seattle, Washington—and he spends a good deal of his time hopping around Alaska. He is an outdoor man in every sense of the word. There are few writers in America who can catch the spirit of the frozen North as he can. His interests lie out under the open sky, with snow fields, fir forests, Canyons and great rivers. It was natural, therefore, that he took to flying.

winter days with snow streaking through the sky, it seems right and proper to introduce Frank Richardson Pierce to you folks. Pierce lives up in the Northwest, up in Seattle, Washington—and he spends a good deal of his time hopping around Alaska. He is an outdoor man in every sense of the word. There are few writers in America who can catch the spirit of the frozen North as he can. His interests lie out under the open sky, with snow fields, fir forests, Canyons and great rivers. It was natural, therefore, that he took to flying.