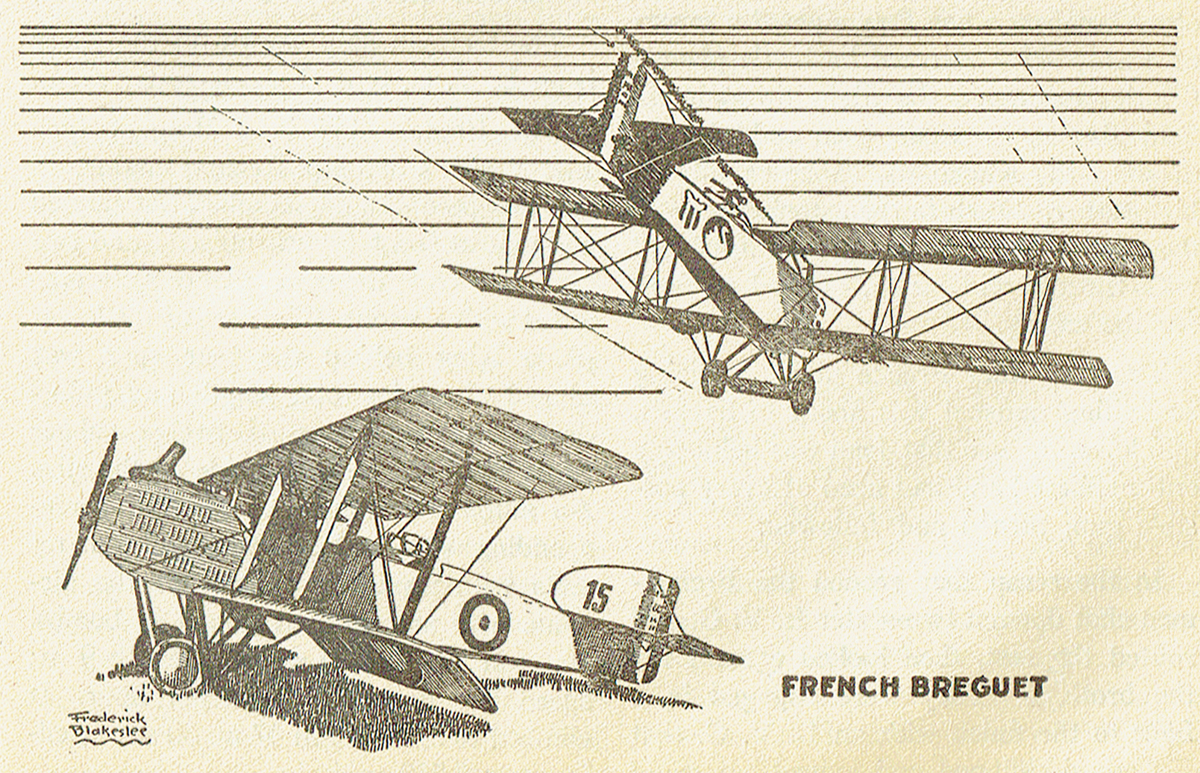

“The French Breguet” by Frederick Blakeslee

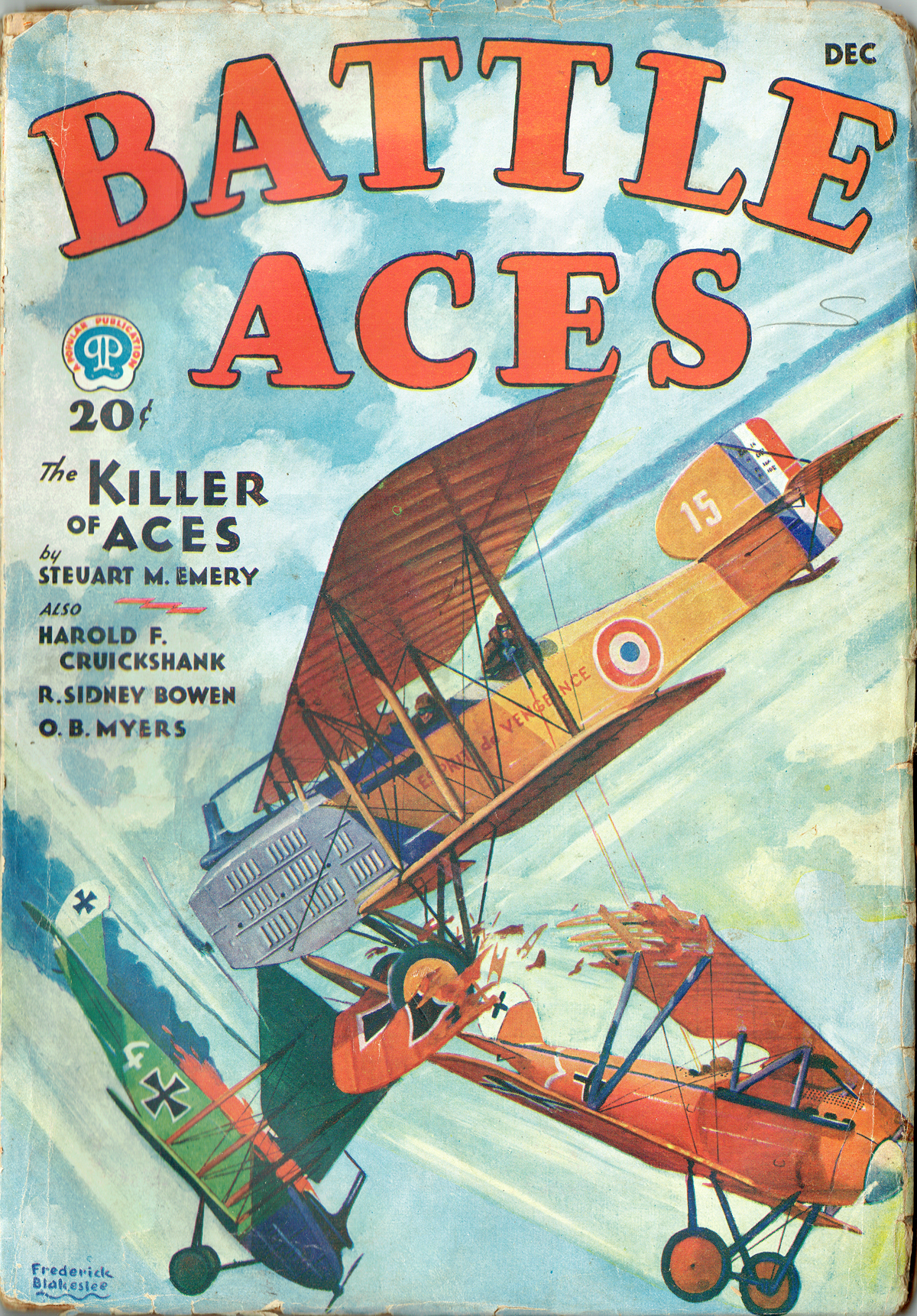

Editor’s Note: This month’s cover is the nineteenth of the actual war-combat pictures which Mr. Blakeslee, well-known artist and authority on aircraft, is painting exclusively for BATTLE ACES. The series was started to give our readers authentic pictures of war planes in color. It also enabled you to follow famous airmen on many of their amazing adventures and feel the same thrills of battle they felt.

THE story behind this month’s cover —which shows an exploit of two brothers, Captains Jean and Charles Ranconcour—had its origin five years before the beginning of the War, when the Frenchmen were visiting Berlin. One evening, while they were dining in a crowded restaurant with a friend, a Prussian officer approached their table and without warning flung a glass of wine into Jean’s face. The three leaped to their feet; Charles demanded an explanation in behalf of his brother. The Prussian turned to him, surveyed him from head to foot, then slashed him across the face with a pair of heavy gloves. Jean promptly knocked him down.

THE story behind this month’s cover —which shows an exploit of two brothers, Captains Jean and Charles Ranconcour—had its origin five years before the beginning of the War, when the Frenchmen were visiting Berlin. One evening, while they were dining in a crowded restaurant with a friend, a Prussian officer approached their table and without warning flung a glass of wine into Jean’s face. The three leaped to their feet; Charles demanded an explanation in behalf of his brother. The Prussian turned to him, surveyed him from head to foot, then slashed him across the face with a pair of heavy gloves. Jean promptly knocked him down.

By this time, of course, a large crowd had gathered and it was with considerable difficulty that order was restored. First Jean, then Charles, challenged him to a duel and the Prussian accepted, telling them to await his seconds. They waited for two hours, only to learn then that their strange enemy had been seen leaving the city—hurriedly; he had heard, no doubt, that both brothers had a reputation as expert duellists.

From that moment the two brothers swore to obtain satisfaction for this cowardly assault—but their opportunity did not come until nine years later high above the battlefields of France.

The outbreak of the War found Jean and Charles officers in infantry regiments. Late in 1917 they received word that the Prussian officer was in a certain Boche aviation squadron. The brothers immediately transferred to aviation and through influence they were both attached to the same French squadron—Jean as pilot and Charles as his gunner.

They got the reputation of being careful fighters. Although they never avoided a combat, neither did they go out of their way to get into one. But as they did their work and were popular no one accused them of cowardice. The more astute among the squadron guessed the truth. From the name they had christened their Breguet and the fact that Charles scrutinized all enemy planes with binoculars, they guessed the brothers were hunting a particular enemy.

One day early in 1918, the brothers were returning from a mission with two other bombers when they sighted a group of enemy ships escorted by battle planes. Charles examined the flight through his field glasses, as usual; then suddenly he dropped the binoculars, spoke rapidly to his brother. Much to the astonishment of their fellow flyers, Jean’s plane turned and with throttle wide open, hurtled straight for the enemy.

The two other French pilots, realizing something unusual was about to happen, and knowing also that Jean was helplessly out-numbered and had need of every possible gun, turned and followed.

In the scrap that ensued the Frenchmen shot down a two-seater L.V.G. and routed the rest, then looked around for the brothers. They were engaged in a fight to the finish with an L.V.G. that turned, sideslipped and looped but could not shake this French terror on its tall. If Jean and Charles had been careful before, their tactics now were completely changed. They fought like fiends.

In trying to escape, the Boche ship turned and came screaming back just as Jean’s plane dove across it. There was a crash as the landing gear carried away the tip of the L.C.G.’s wing. At the same moment Charles poured a murderous— and fatal—fire into the cockpit.

The L.V.G. dove and crashed. When he had seen it hit the earth, Charles cooly climbed down onto the landing gear and disentangled the wreckage. A few minutes later all three French ships landed near the shattered Boche plane. The body of the German was dragged from the wreckage; Jean and Charles bent over it, looked closely, then straightened and shook hands. The duel to which they had challenged this enemy 9 years ago, had been waged—and won.

The brothers transferred to a combat squadron soon after and both piled up a formidable score before the war ended.

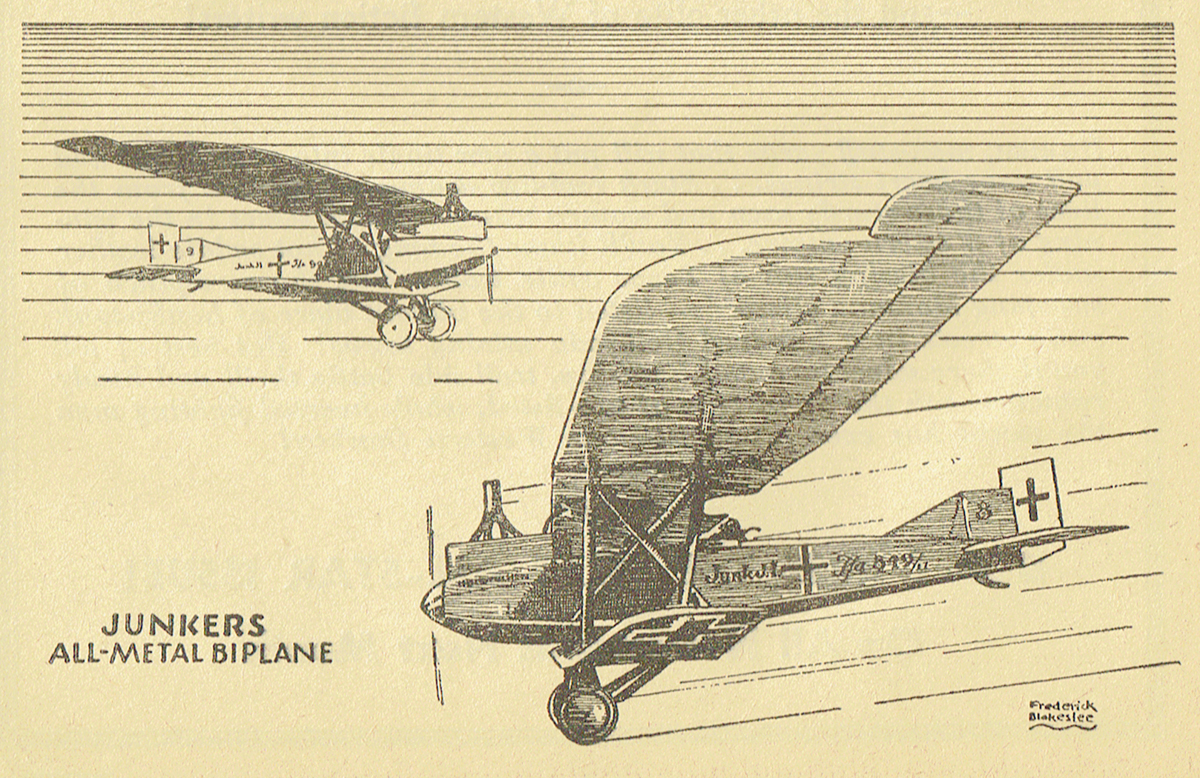

The German ship shown on the cover is an L.V.G. type D single-seater scout.

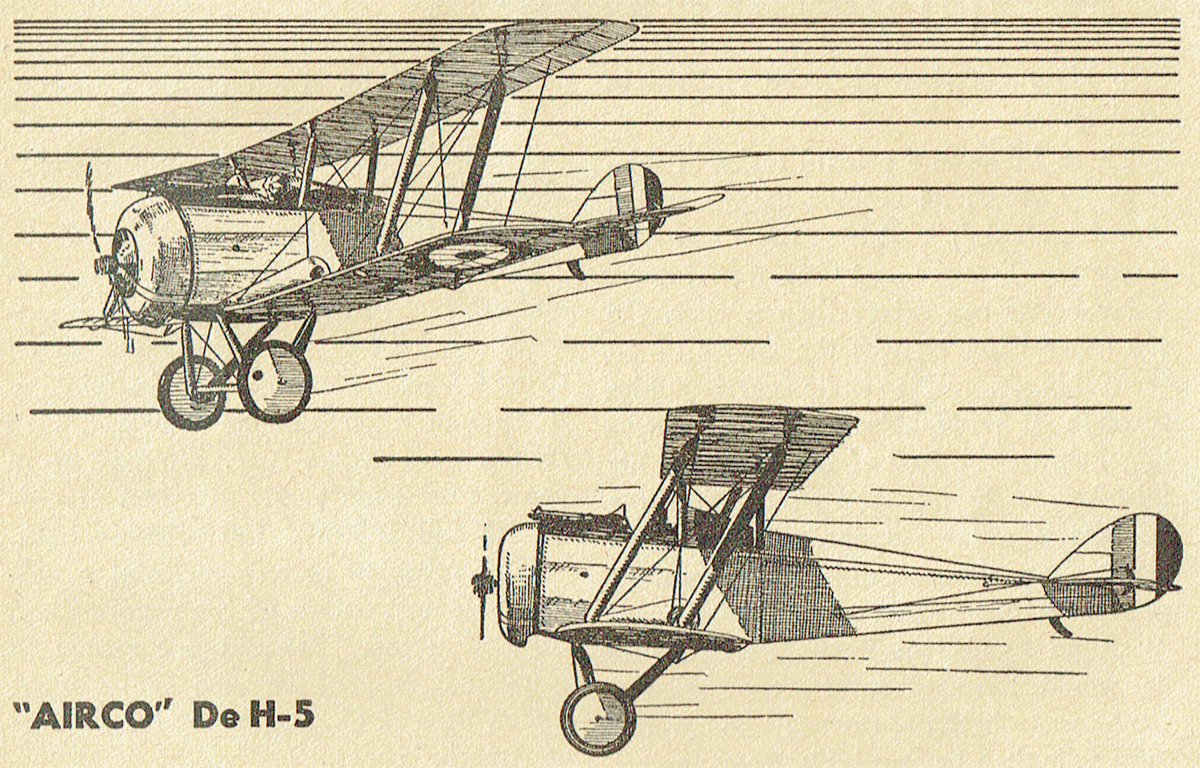

The French ship is a Breguet type 14B-2 with a 300 h.p. Renault engine. It was designed as a day bomber, but carried one gun in front (synchronized) and two guns aft. Only the upper planes were provided with ailerons. The part of the lower plane lying behind the rear spar was hinged along its total length and pulled downward by means of twelve rubber cords fixed on the under side of the ribs. An automatic change of aerofoil corresponding with the load and speed thus results with an easier control of the airplane with and without a load of bombs. Its span was 14.364 meters; length 9 m; speed low down 185 kms per hour. It climbed to 5,000 m. in 47 m. 30 sec. Ceiling was 5,750 m.

“The French Breguet” by Frederick M. Blakeslee (December 1932)

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

of

of

known as the man behind

known as the man behind

of

of