“Flying Aces, December 1934″ by C.B. Mayshark

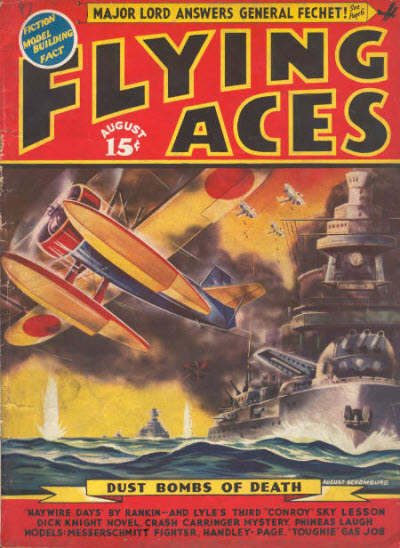

THIS May we are once again celebrating the genius that is C.B. Mayshark! Mayshark took over the covers duties on Flying Aces from Paul Bissell with the December 1934 issue and would continue to provide covers for the next year and a half until the June 1936 issue. While Bissell’s covers were frequently depictions of great moments in combat aviation from the Great War, Mayshark’s covers were often depictions of future aviation battles and planes—Case in point, for three issues, starting with the December 1934 issue, Mayshark depicted Air Battles of the future! For the December 1934 issue Mayshark gives us The Rocket Raider!

Air Battles of the Future: The Rocket Raider

THE future war in the air has the national defense experts puzzled as to what methods of attack may be used and what systems of defense may be required to maintain public security. In general, the aviation experts agree that few ships in modern use today would be able to withstand the onslaught of several air weapons that have already been devised and, in many cases, actually built and flown. These weapons include gas distributors, stratosphere ships, radio-controlled torpedo planes and various types of rocket-propelled machines.

THE future war in the air has the national defense experts puzzled as to what methods of attack may be used and what systems of defense may be required to maintain public security. In general, the aviation experts agree that few ships in modern use today would be able to withstand the onslaught of several air weapons that have already been devised and, in many cases, actually built and flown. These weapons include gas distributors, stratosphere ships, radio-controlled torpedo planes and various types of rocket-propelled machines.

Should any of these devices be brought into play today, it is evident that we have little with which to combat them. Take the case of the rocket ship, for instance. It is not a figment of the imagination, in any sense. Rocket ships and rocket automobiles have been built and actually flown or run. Rocket boats have been propelled successfully at high speed. A controlled rocket system is actually in operation in Europe, and plans are under way to deliver mail from the center of Germany to England next summer. How far away, then, is the military rocket ship? Possibly a year, possibly five.

But suppose that some foreign power has a rocket ship—a small fleet of them. If we believe facts and figures as shown, a large rocket ship, capable of carrying large bomb loads and heavy gun-power, could cross the Atlantic or the Pacific in about ten hours. Let us suppose, for instance, that such a ship or a fleet of ships were to attack the American mainland.

For one thing, this raid would not be discovered at once—probably not before the fleet was within one hundred miles of the coastline. Immediately, the General Staff would realize the seriousness of the situation. It might mean the destruction of government nerve centers. It might indicate terrible bombing, or the spreading of gas or disease germs. The knowledge of who the possible enemy was would give the first inkling of the points of attack. Naval bases might be threatened, and aircraft factories.

If big cities were to come in for the threat, it would mean death and destruction amid the civil population. Water supplies might be cut off, power and communication systems destroyed. But one of the most important points to be considered in a raid of this sort would be the grim element of blasting surprise and demoralization of morale among the civil population.

A scene prophetic of such a situation might be constructed on the air field of an Army Air Service squadron—let us say, along the Atlantic Coast. The sound-detectors have picked up a suspicious sound, a sound not quite like anything ever caught before. The detector-operator senses that this is no ordinary internal combustion engine, and at once his fears begin to gather, for he has been warned of possible raids by strange aircraft. What can this powerful engine threaten?

A fleet of Army Boeings is sent out to attempt to contact this ship. They are equipped with two-way radio sets, so they are sent out fanwise to cover as wide an area as possible and with orders to report the position of the on-rushing winged weapon.

The pilots—young, anxious, but a little skeptical about all this talk of strange foreign raiders of such monstrous proportions and ability—climb into their ships under the hasty commands of their field commandant.

As the pilot jams the gas into the 500-h.p. Wasp engine, the Boeing P-12E strains forward and is off the tarmac with a roar. Climbing in a spiral, the ship reaches six thousand feet in 3.5 minutes, levels off, and heads to the east. The pilot of the Boeing searches the skies before him and spots an object just above the horizon. Within the next minute, all his illusions about the possibilities of a rocket raid on the United States are gone.

Tearing down across the sky at a phenomenal rate of speed, there appears before the eyes of the Boeing pilot a long, black, perfectly streamlined hull supported in the air by stubby yellow wings. As the strange machine bursts into a better line of vision, the mechanical detail is easily distinguished. The rocket projection tubes are located near the aft end of the ship, and are placed so that the tail assembly will not interfere with the rocket bursts as they are emitted. On top of the rudder is a machine gun which fires in the direction that the rudder is set. The cartridge belt passes within the framework of the rudder down to the magazine, which is located in the tail of the hull. Two 37-mm. air cannons are carried in the wings. These guns are stationary, and they fire forward in the line of flight.

Other armament consists of a bullet-proof, glass-covered gun turret directly in front of the control cabin, and a fixed, steel-covered cannon turret above and to the rear of the control cabin. The ship is equipped with wheels and pontoons, both of which are retractable. Complete radio equipment is carried, including transmitter and receiver and a television screen. Except for the reserve tank, the rocket fuel is carried in ten individual containers, which feed directly to their respective rocket projection tubes. The carburetor and firing unit are located in the elbow of the tube, so that when the explosion occurs, the burst carries itself without friction with anything but air, past the tail and directly to the rear of the ship, thereby producing forward motion.

The crew consists of seven men, including the commanding officer, the pilot, the navigator, the radio operator, two gunners, and the engineer. The machine is covered with a lightweight composition sheet metal which is as strong as steel. The ship attains a speed of between 600 and 700 miles per hour, but the landing speed is relatively low, due to the fact that forward motion can be reduced simply by reversing the position of two of more of the rocket projection tubes, all of which are mounted on a swivel and can be turned to any point within 180 degrees.

Our pilot in the Boeing barely has time to collect his senses before the roaring rocket raider is all but upon him. As he kicks his trim little ship over in the air, he feels the impact of steel-jacketed bullets on his fuselage and realizes with anger that the gunner in the glass turret of the rocket demon is already firing on him! He pulls up and drops over into a half-roll in an attempt to maneuver out of the line of that deadly fire.

At last he is in the clear and, as he trains his wing guns upon the flashing hull of the rocket ship, he realizes that there are no visible vital spots at which to aim. All he can do is fire point blank and trust that he hits a control surface with damaging effect. During the few seconds that his enemy remains in his line of fire, he keeps his fingers on the trigger buttons, but the bullets bounce off the steel ship like hailstones off a tin roof.

In a vain attempt, our Boeing pilot dives down, firing at the tail of the giant ship. But suddenly he finds himself being racked by the terrific fire of his adversary’s rudder gun. Frantically he pulls his damaged ship over and slides into a slow spin. He lands a few moments later, scarcely able to explain what he has seen, owing to his excitement. But the rocket raider continues on to the west, unchecked. Where will it strike, and how will it be stopped? It will be coped with, there is certainly no doubt, but a much faster and more powerful ship than the Boeing P-12E will be required to bring it to its doom.

Flying Aces, December 1934 by C.B. Mayshark

Air Battles of the Future: The Rocket Raider

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

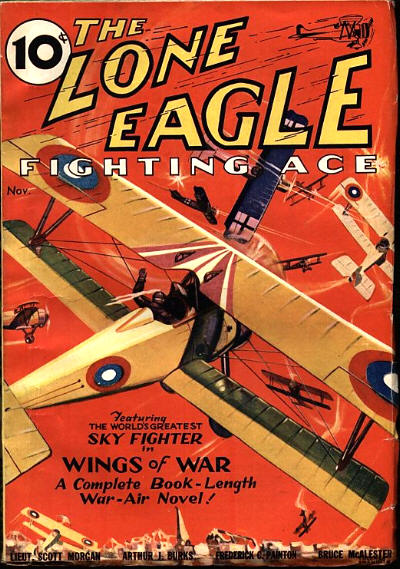

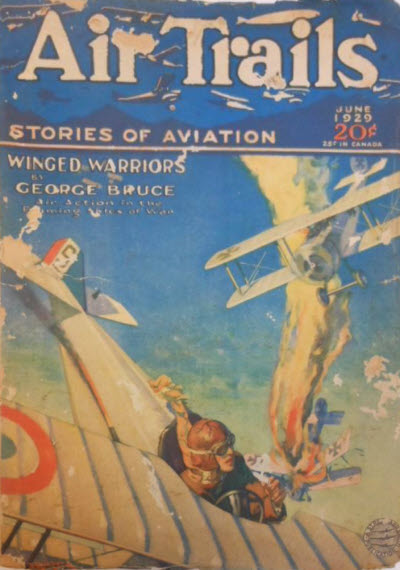

THIS week we have a story by prolific pulpster—Arthur J. Burks! Burks was a Marine during WWI and went on to become a prolific writer for the pulps in the 20’s and 30’s and was a frequent contributor to the air war pulps like The Lone Eagle.

THIS week we have a story by prolific pulpster—Arthur J. Burks! Burks was a Marine during WWI and went on to become a prolific writer for the pulps in the 20’s and 30’s and was a frequent contributor to the air war pulps like The Lone Eagle.

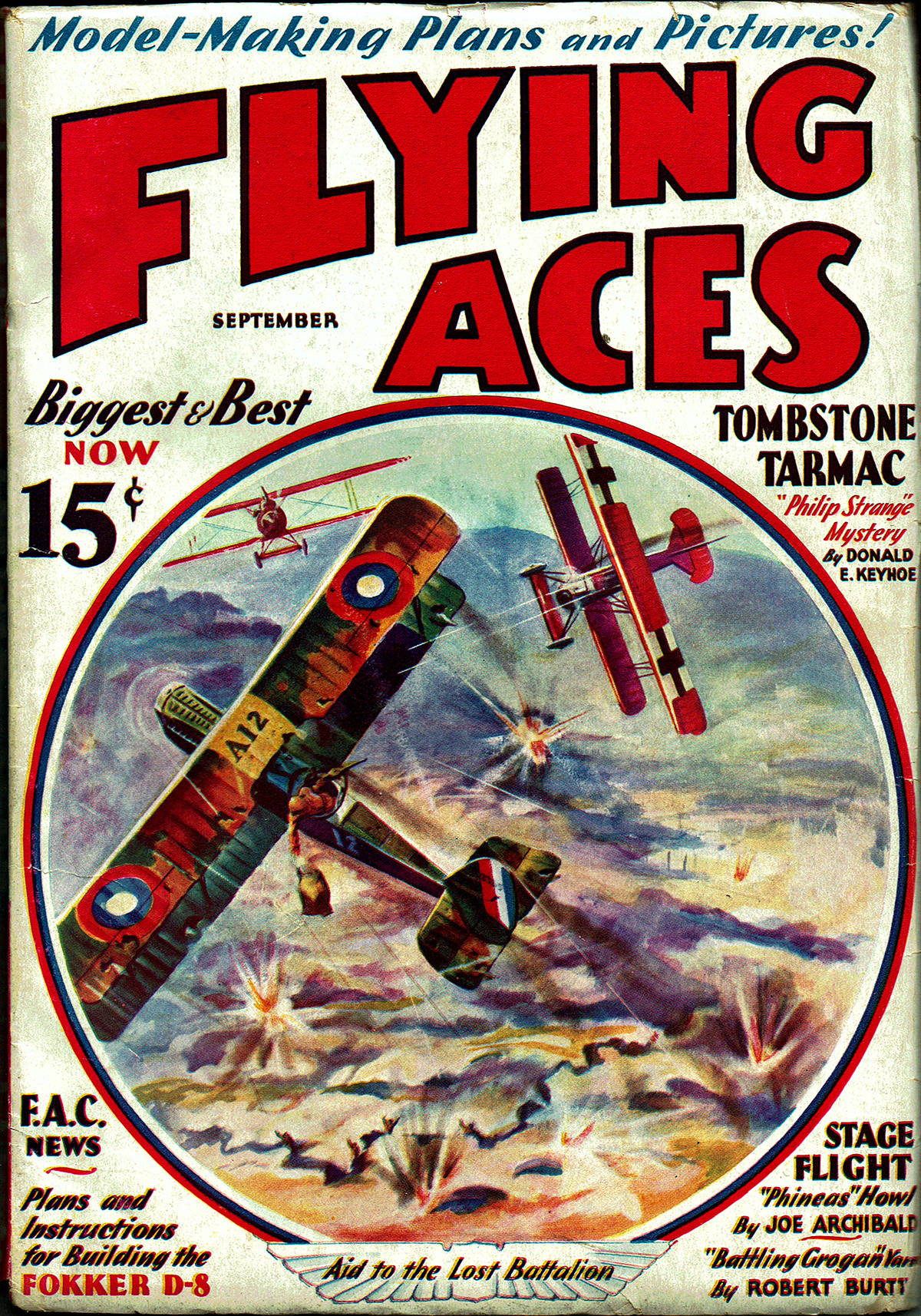

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

exciting air adventure with Rusty Wade from the pen of Frank Richardson Pierce. Pierce is probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

exciting air adventure with Rusty Wade from the pen of Frank Richardson Pierce. Pierce is probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

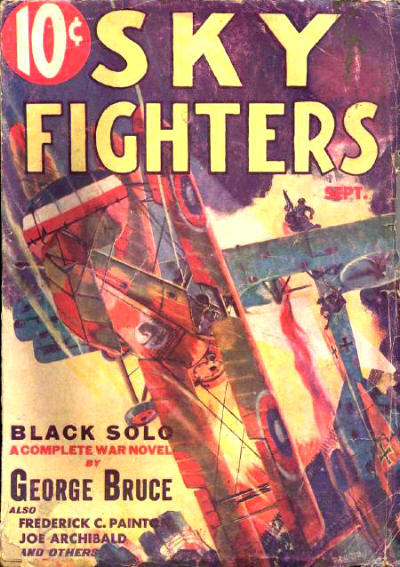

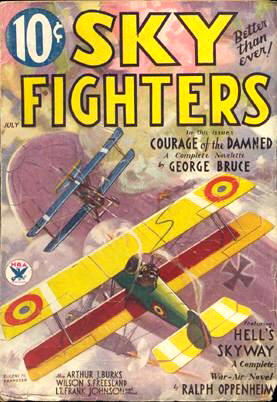

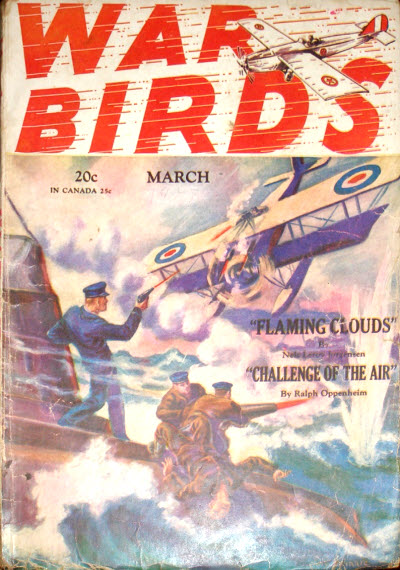

Mosquito Month we have a non-Mosquitoes story from the pen of Ralph Oppenheim. In the mid thirties, Oppenheim wrote a half dozen stories for Sky Fighters featuring Lt. “Streak” Davis. Davis was a fighter, and the speed with which he hurled his plane to the attack, straight and true as an arrow, had won him his soubriquet. And time is of the essence when Streak is sent on a bombing mission. He must destroy the Krupp Machine works at Luennes before they unleash German’s newest secret weapon at noon! From the July 1934 issue of Sky Fighters it’s “Hell’s Skyway!”

Mosquito Month we have a non-Mosquitoes story from the pen of Ralph Oppenheim. In the mid thirties, Oppenheim wrote a half dozen stories for Sky Fighters featuring Lt. “Streak” Davis. Davis was a fighter, and the speed with which he hurled his plane to the attack, straight and true as an arrow, had won him his soubriquet. And time is of the essence when Streak is sent on a bombing mission. He must destroy the Krupp Machine works at Luennes before they unleash German’s newest secret weapon at noon! From the July 1934 issue of Sky Fighters it’s “Hell’s Skyway!”

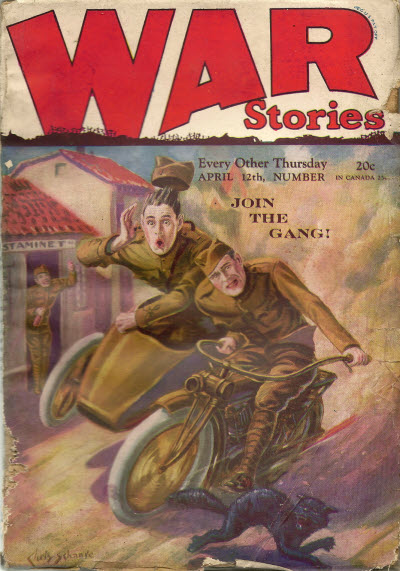

the third and final of three Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes stories we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! And this one’s a doozy! Kirby gets the unenviable job of test flying the new type Spad and putting it through its paces—including trying it in combat and shooting down a plane. But, under no circumstances should he take the new plane over the lines! Unfortunately that’s just what Kirby did! Read all about it in Ralph Oppenheim’s “An Ace of Spads” from the April 12th, 1928 issue of War Stories!

the third and final of three Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes stories we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! And this one’s a doozy! Kirby gets the unenviable job of test flying the new type Spad and putting it through its paces—including trying it in combat and shooting down a plane. But, under no circumstances should he take the new plane over the lines! Unfortunately that’s just what Kirby did! Read all about it in Ralph Oppenheim’s “An Ace of Spads” from the April 12th, 1928 issue of War Stories!

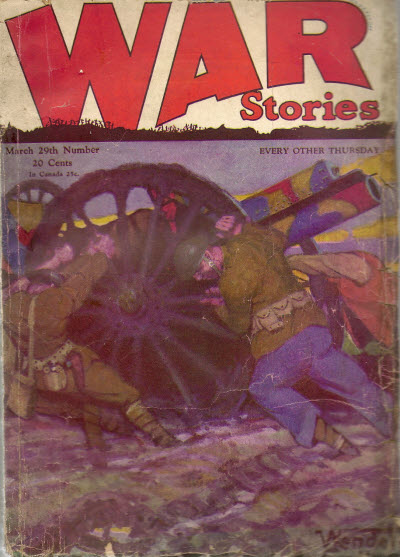

the second of three tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, the intrepid trio is tasked with getting valuable information from behind German lines—but it’s a job for only one man which unfortunately turns into one man at time as each of the Mosquitoes is sent off to garner the information when the previous one fails to return. From the March 29th, 1928 issue of War Stories, it’s The Three Mosquitoes in “An Ace in the Hole!”

the second of three tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, the intrepid trio is tasked with getting valuable information from behind German lines—but it’s a job for only one man which unfortunately turns into one man at time as each of the Mosquitoes is sent off to garner the information when the previous one fails to return. From the March 29th, 1928 issue of War Stories, it’s The Three Mosquitoes in “An Ace in the Hole!” hit the stands in February 1928, it not only contained an exciting tale of Ralph Oppenheim’s inseparable trio The Three Mosquitoes, but it also had a rare factual piece by Mr. Oppenheim. Ralph and his younger brother Garrett had taken a trip to Europe the previous year and just happened to be there at the right time to be able to get to Paris and be there at Le Bourget Field on the 21st of May when Charles Lindbergh successfully ended his trans-Atlantic flight!

hit the stands in February 1928, it not only contained an exciting tale of Ralph Oppenheim’s inseparable trio The Three Mosquitoes, but it also had a rare factual piece by Mr. Oppenheim. Ralph and his younger brother Garrett had taken a trip to Europe the previous year and just happened to be there at the right time to be able to get to Paris and be there at Le Bourget Field on the 21st of May when Charles Lindbergh successfully ended his trans-Atlantic flight!