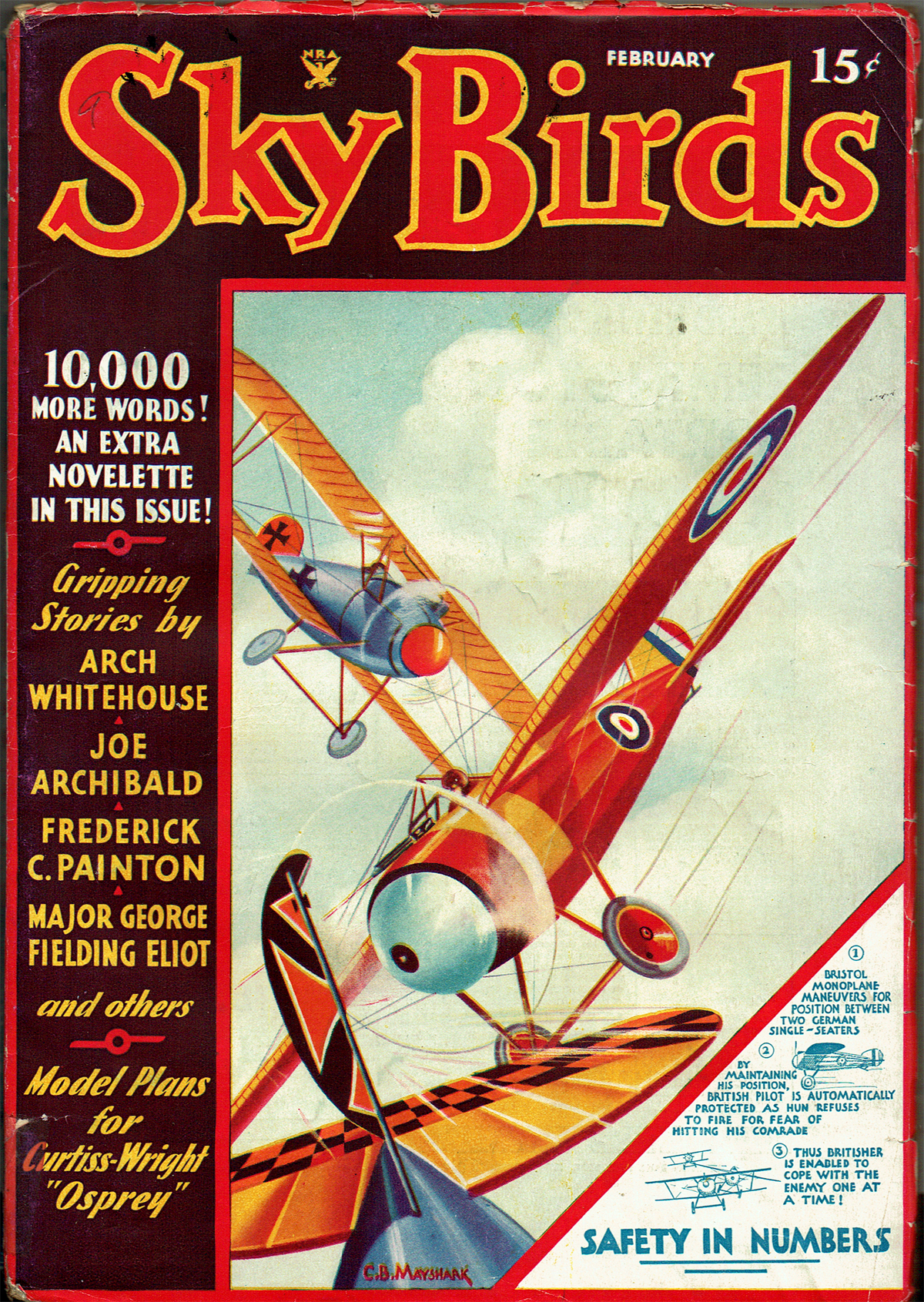

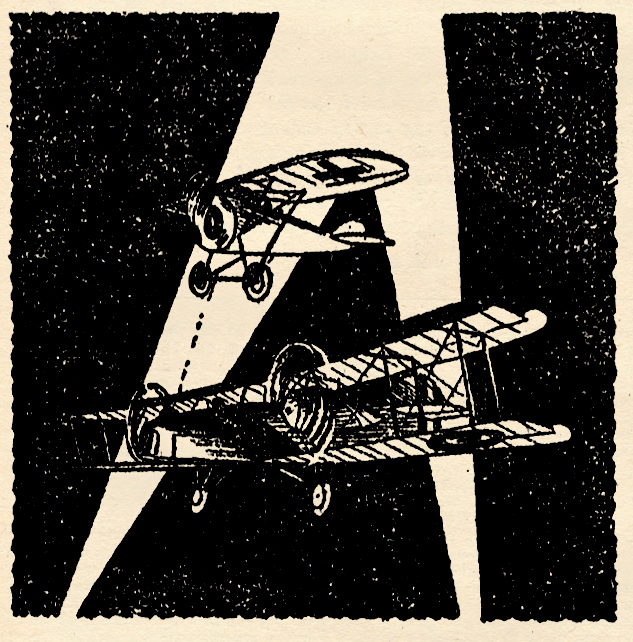

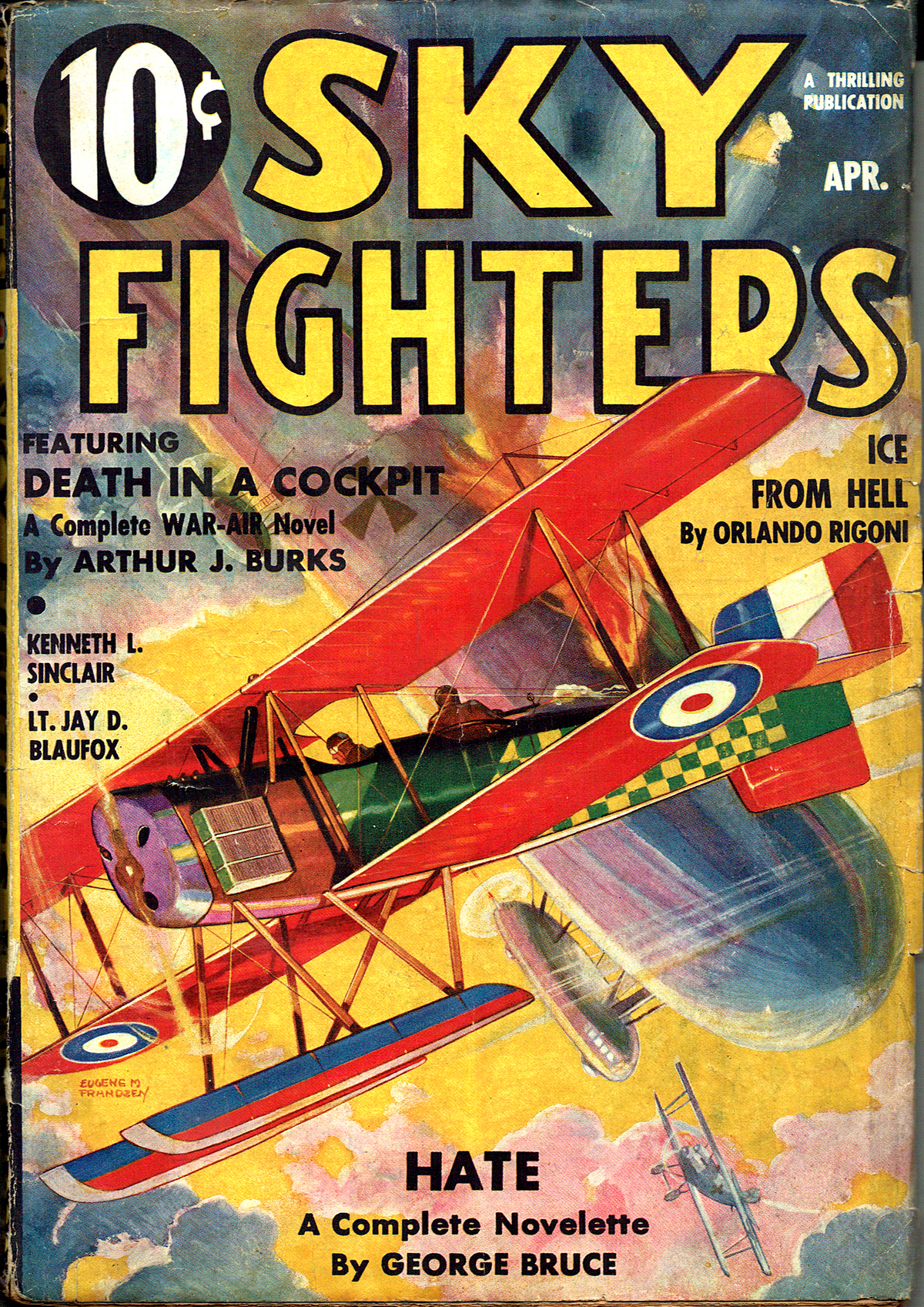

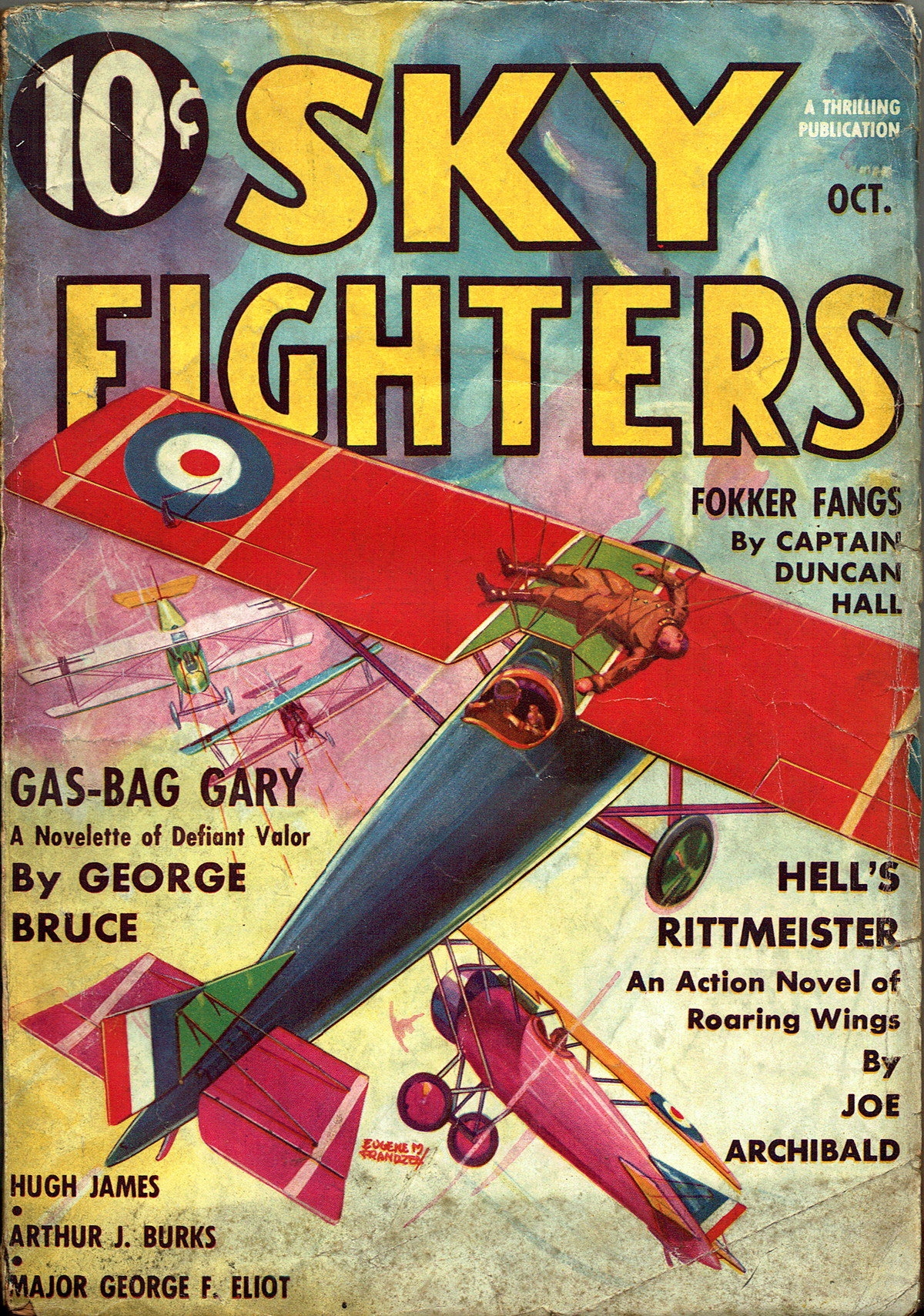

“Sky Fighters, October 1936″ by Eugene M. Frandzen

Eugene M. Frandzen painted the covers of Sky Fighters from its first issue in 1932 until he moved on from the pulps in 1939. At this point in the run, the covers were about the planes featured on the cover more than the story depicted. On the October 1936 cover, It’s the Morane-Saulnier 27C1 & Roland D2!

The Ships on the Cover

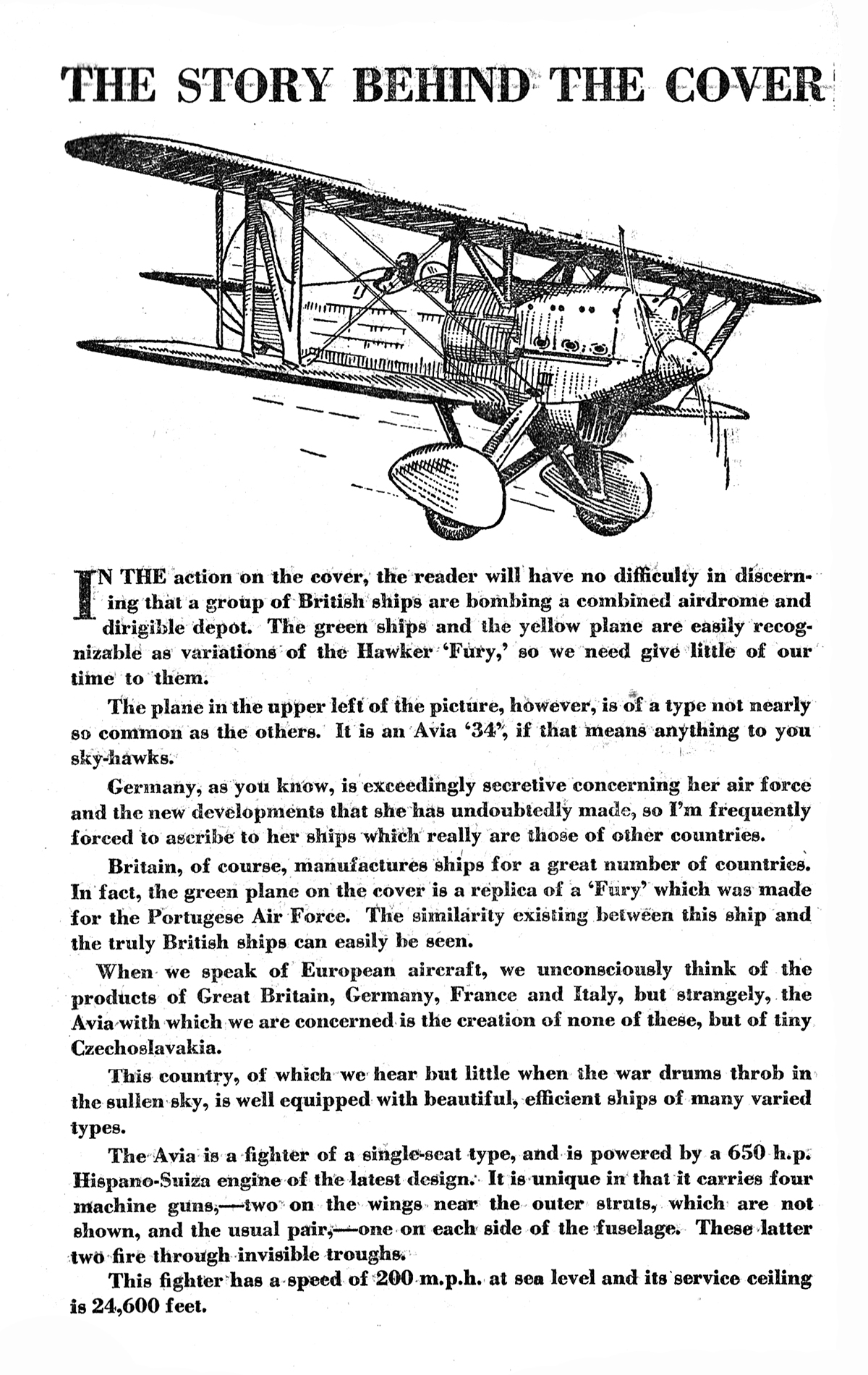

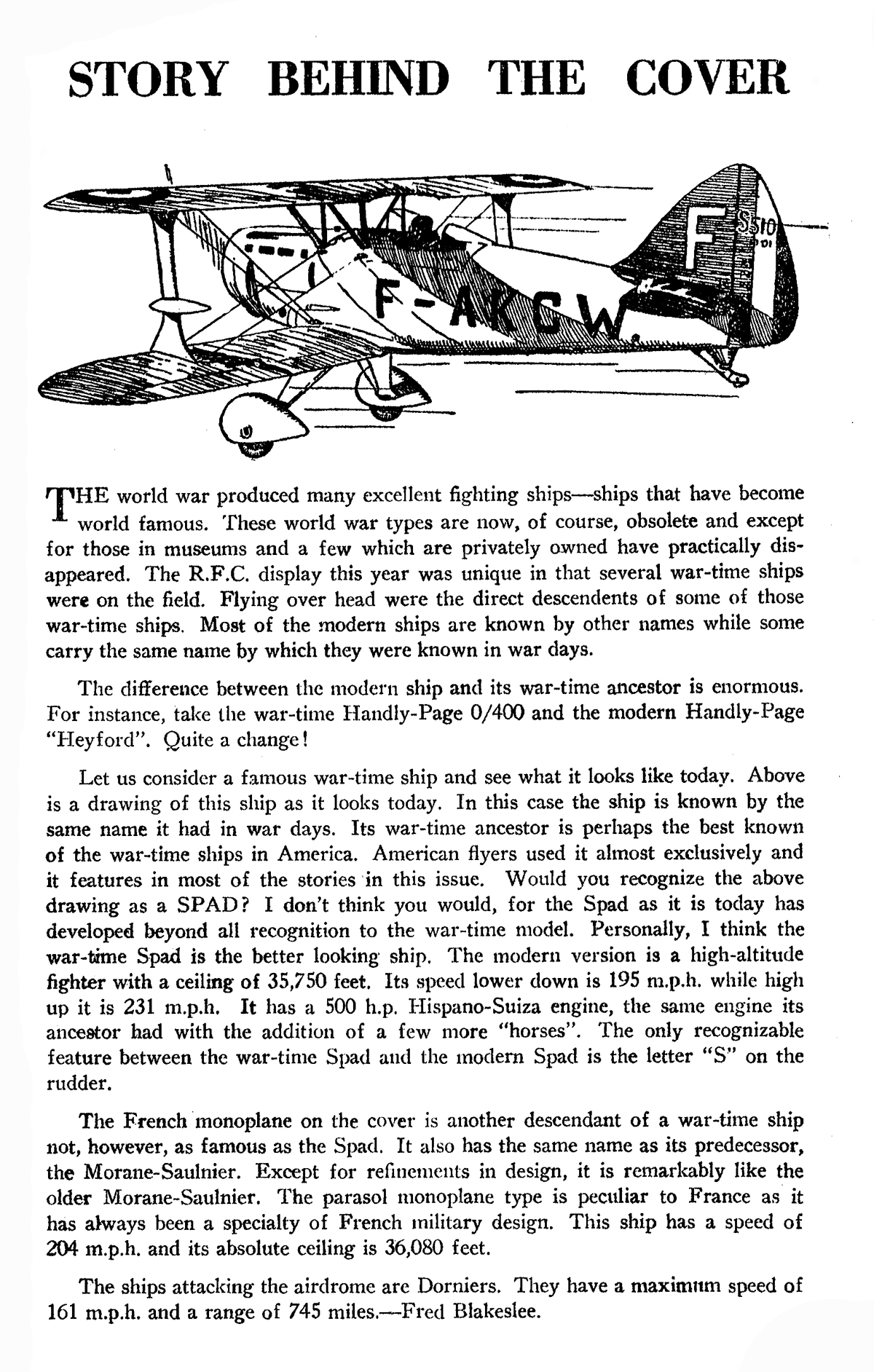

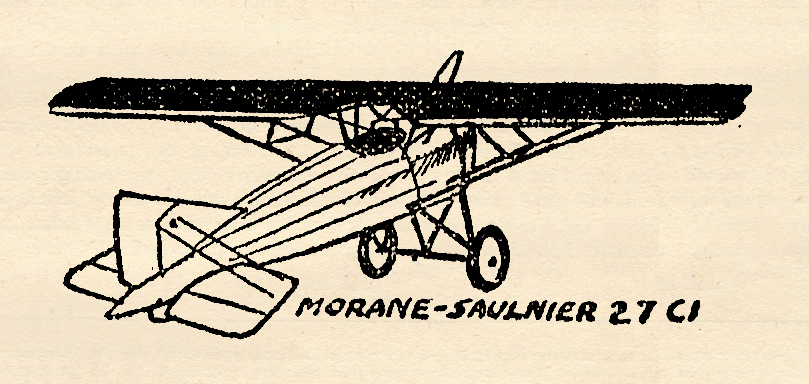

THE French developed  the outstanding monoplanes of the Parasol type produced during the war. The early Morane-Saulnier Parasols were very successful and the later war models progressed with the quick advance of aviation but continued the main design features of the original Parasols. The Morane-Saulnier 27 C1 was a single-seater righting scout which carried substantial strut bracing to the wings instead of the large number of wire braces used on previous monoplane models. The rounded fuselage housed a 160 h.p. Gnome motor.

the outstanding monoplanes of the Parasol type produced during the war. The early Morane-Saulnier Parasols were very successful and the later war models progressed with the quick advance of aviation but continued the main design features of the original Parasols. The Morane-Saulnier 27 C1 was a single-seater righting scout which carried substantial strut bracing to the wings instead of the large number of wire braces used on previous monoplane models. The rounded fuselage housed a 160 h.p. Gnome motor.

This understrut bracing of the high wing Parasol has not really been abandoned. Many of our high winged monoplanes, although not strictly Parasols, never-the-less are closely related to the old Moranes. Our Stinson, Bellanca and several others with the understrut bracing, merely have the fuselage and cabin fused in with the top wing. It was a good stunt in the old days. It’s a good stunt now. A forerunner of the Morane-Saulnier Parasol was called the Aerostable on account of its inherent stability. It had no ailerons, so it was up to the pilot to shift his weight in his seat to give lateral control.

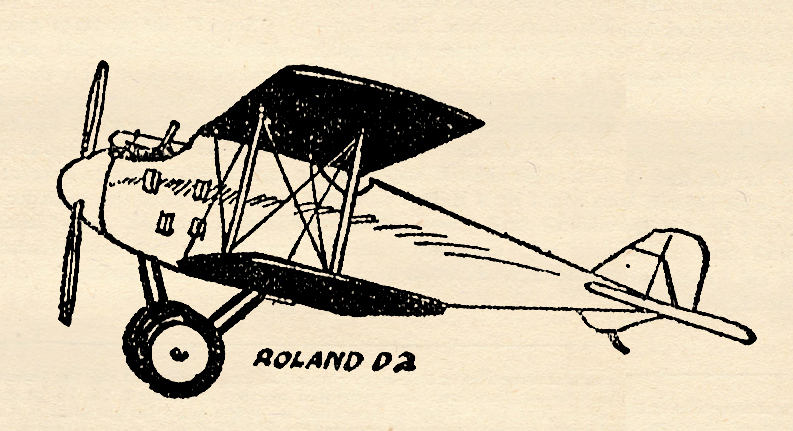

The Roland Seemed Impractical

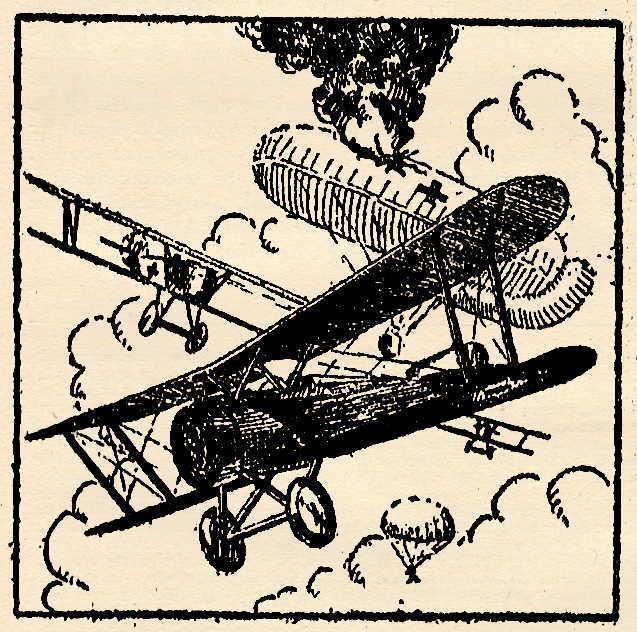

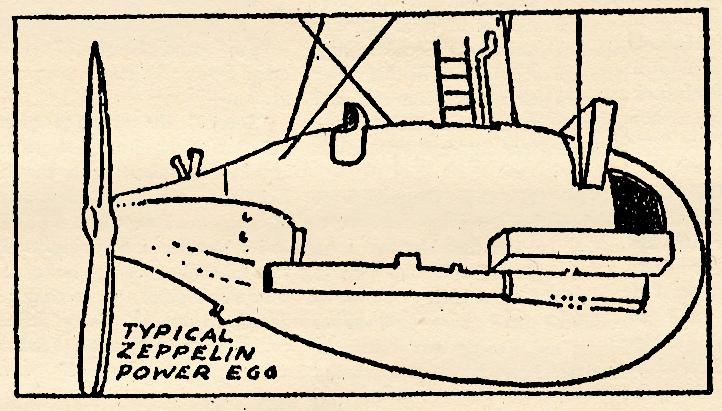

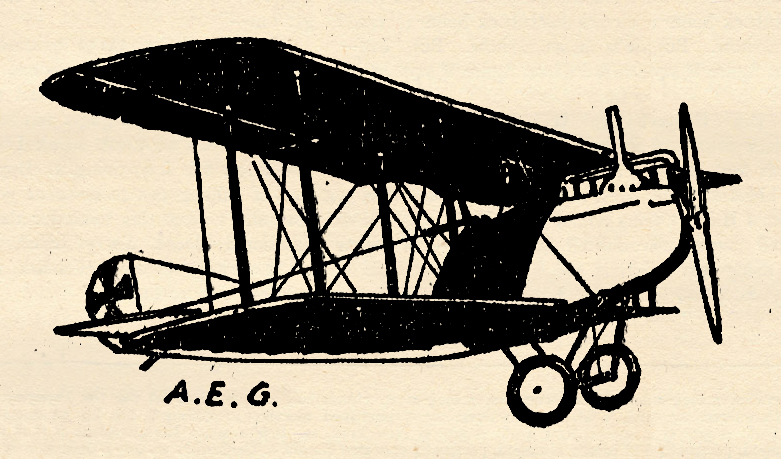

The German plane known as the L.F.G, Roland had an original design which was seemingly so impractical that the firm, Luft Fahrzeug Gesellschaft was safe from anyone stealing their idea. The Roland D2 was a single-seater fighter in which this design was incorporated. The fuselage under the top wing was carried up to the wing cutting off the pilot’s view in front, even though this superstructure did thin out considerably at the top and left room for two windshields, one on each side of the center ridge. Despite this drawback the D2 was a good ship and was still used in many German squadrons in 1918. The 160 h.p. Mercedes may have been partly responsible for the good qualities of the D2’s performance but even with a good power plant it was against all reason to park a solid mass in front of the pilot’s eyes. It would be just as practical to put a strip of tin six inches wide smack down the windshield of your car directly in front of the steering wheel. But just a few dozen cockeyed hunches like that thrown into the war crates gave the civil designers plenty of precedents of what not to do when the war was over.

Possibly if war comes in the future it will be a mass of planes against a like mass of enemy’s fighting planes. Aces will be a thing of the past. A few men will be outstanding in their flying but it will be hard to observe their deeds in the terrific rnixup that must occur far overhead, possibly out of sight. Publicized stunts will be few and far between, but to cut out entirely from the picture the personal element of friendship and cooperation between men of a squadron will be impossible!

Saving a Buddy

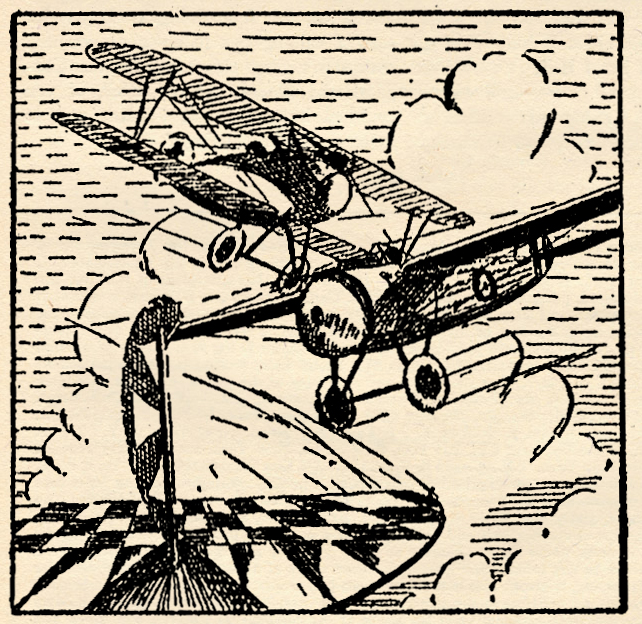

The Morane pilot on the cover knew exactly where a buddy, who had been taken prisoner from a cracked-up plane, was confined in a hospital in a small suburb. He communicated with his friend by those devious means that humans will always work out some way, despite the vigilance of the enemy’s espionage system. The man in the hospital feigned lameness longer than necessary and at a prearranged moment, while the Morane was landing at an adjacent field, he swung his crutches with vim and vigor. Down went the two unarmed attendants. In ten minutes he was securely tied to the top of the Morane’s wing and high in the air headed for home. Another Parasol joined the French plane and drove off two Roland D2s who had sighted the overburdened Morane and considered it easy pickings.

The personal touch was in that quickly executed rescue. War will always have those daring exploits. Friendships formed under fire are lasting and strong.

Sky Fighters, October 1936 by Eugene M. Frandzen

(The Ships on The Cover Page)