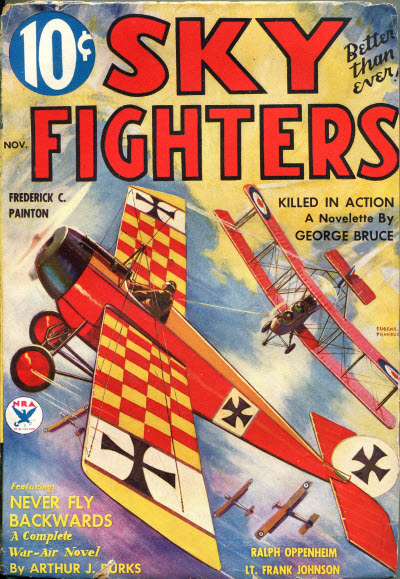

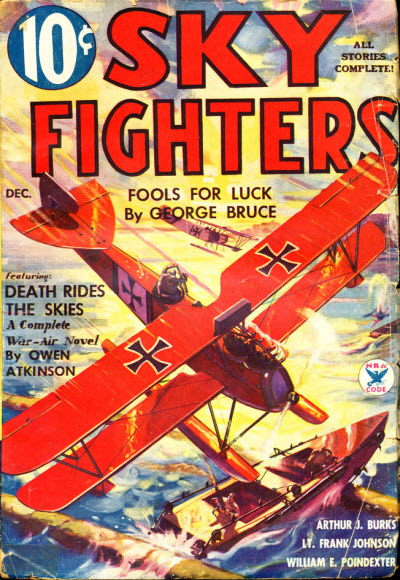

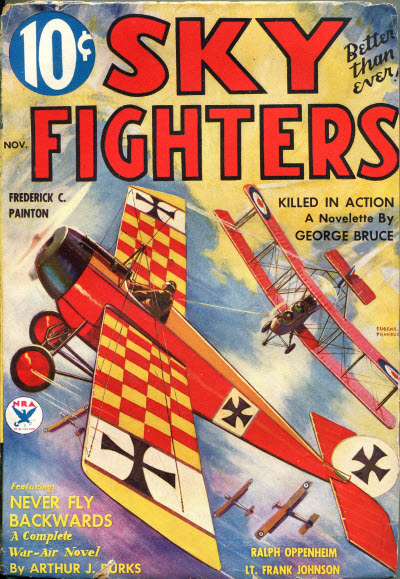

FROM the pages of the November 1934 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

Personalities of the Planes

by Lt. Edward McCrae (Sky Fighters, November 1934)

NOW if you youngsters will get the gun cotton out of your ears I’ll tell you something that you might not have thought of before. I’m going to tell you why they sometimes call an airplane “she” just like they call a steamship or sailing ship “she.”

It’s because they all have personalities of their own, and because their personalities are so cranky usually that you can’t expect to know what they’re going to do next until you get well-acquainted with them, and by that time you don’t care much what they do. So, having personalities so much like women, we naturally call them “she” and a lot of other names that you cannot write about in a magazine.

So, if you’ll sit up I’ll try to introduce you to a bunch of the ladies and tell you some of the little things about them that you don’t ordinarily hear when they just tell you their names and addresses.

Most of ’Em British

Now most of the ladies we Americans got acquainted with were British, with just a few French gals thrown in to make it exciting.

For instance, the first lady your Uncle Eddie met when he got over in nineteen-fifteen was a gal who had just been built and had officially been named the E.F.B.5.

But that name naturally wouldn’t do for us, so we quickly got to calling her the Vickers Gun Bus, Fig. 1, You see, at this time, the war was just getting under way like it meant real business, and it had become apparent to the big shots that the airplane was going to play an important part in it.

Some Advance!

Before that they had been sending ships up with the pilots armed only with pistols or carbines or brickbats. But that didn’t work so well, so the result was an airplane with a machine-gun attachment. And boy, in those days that was some advance.

But you should have seen that old Gun Bus. Today you’d laugh your head off just looking at it, but we took it pretty seriously. She was the most famous of the early crates.

To look at her you would think the designer got his idea from a flying coffin. The nacelle sat up in front and stuck out forward of the wings. Behind the nacelle or fuselage if you could dignify it by that name—which you couldn’t—was a lot of outrigger gear with a tail stuck on it. It looked kind of like a small windmill stand sticking outward to the rear.

And then the wheels were back to the rear of the center of gravity and they had one of those landing skid arrangements in front of it so you wouldn’t nose over and bash in your face.

The Latest Thing

But boy, in those days here was what we called the latest thing in ladies of the air. The thing had a gun mounted on it, and if you don’t think that was a welcomed innovation you should have been there. The gunner sat out in front in that little cockpit of his with nothing but a lot of ozone under him, and shouted for the Heinies to come up and see me some time. He thought he was sitting on top of the world, which he was, because that gun stuck out so far in front that he had all kinds of angles through which he could aim it.

And the gal was the talk of the town because she was fast—or at least what we thought was fast in those days.

She could hit off at least sixty and seventy miles an hour! And was that getting there?

She Had B.O.

But she fitted in with those present-day soap ads. People whispered behind her back. She had B.O. That was because her 80 h.p. Gnome rotary motor burned castor oil—and no lady motor can burn that stuff and have her friends around without their holding their noses.

Anyway, she was a good old ship until a Miss Sopwith, Fig. 2, came along. That was in nineteen-sixteen, and this new gal was right up to the minute. She was beginning to look like an airplane. And just like the women in those days who tried to see how much wingspread they could carry by making their hats bigger and bigger, this Sopwith went in for wingspread in a big way by taking on an extra wing, becoming a triplane.

We kind of liked the miss because she could get upstairs in a hurry, faster in her time than any other gal on the front. But she was like a lot of the other high flyers and was unreliable in the pinches.

When You Wanted to Dive

There were times when you wanted to dive and dive in a hurry. And in times like this you felt a little worried about the gal because she could go up fast enough but she couldn’t take a dive either fast enough or safe enough to suit your hurry. It was there she showed her weakness.

Once in a while when you wanted to get back to the ground worse than you wanted to do anything else in the world she’d take you down all right—by shedding her wings. That let you down fast enough—but never easy enough. They often had to pick you up with a shovel and broom.

But she was a smart-looking gal, and so the Germans came out with their famous Fokker Triplane, Fig 2. There is plenty of argument as to whether they swiped the Sop design lock, stock and barrel. Most of us believe they did. And there’s plenty of proof. You know, if you steal a lead nickel you’ve got a piece of money that isn’t any good. The Germans’ idea wasn’t any better. They swiped the Sop, and the result was that the Fokker had just the same trouble we did. They built the ships faster, and the result was they lost more wings. There ought to be a moral hidden in that if you can find it.

The Flyers’ Sweetheart

And just about that time was born the sweetheart of all flyers—the Bristol Fighter, Fig 1. Just to prove what a good gal she was it is only necessary to say that she was the only ship that the British held on to long after the war. In fact, she wasn’t declared obsolescent until nineteen-thirty-two. That’s a mighty long life for any type of airplane, what with the steady advance of design.

She was a two-seater that had more uses than the proverbial “gadget.” They were originally intended for reconnaissance-fighters, but it wasn’t long before they used her for almost everything. She toted bombs, did photographic duty, spotted for artillery and even strafed trenches, besides being used for escorts and training. She was one gal you could stunt with and have hopes of setting her down intact when you got through.

Equipped with Stingers

And she was welbequipped with stingers. She had a Vickers gun synchronized through the prop and a Lewis gun on the scarff ring in the rear cockpit. They started her out in nineteen-seventeen with a 200 h.p. Hisso or Sunbeam Arab and got 120 m.p.h. out of her. Then they gave her a 250 Rolls-Royce Falcon and kicked her speed up to 130 m.p.h. She could take it. With that new powerhouse you could boot her up to 15,000 feet in twenty minutes, which was climbing in them days! And she had a slow landing speed of 45 m.p.h.

And she was just a nice size for proper handling, having a 39-foot, span and a 25-foot length, with a height of ten feet and a five-foot-six chord. It’ll be a long time before another ship gets as far ahead of her time as that Bristol baby. I knew her well.

A Great Family

But it seems like we couldn’t stay away from the Sopwith girls. That was a great family. So here before we knew it was another one of the sisters all rigged out and ready to step. She was the Sopwith Pup, Fig. 3. She made her debut in nineteen-fifteen and sixteen. And she was a knockout for beauty. She wore an 80 h.p. LeRhone Rotary in her hair and could get over the country, considering her small power plant.

She could get off the ground in a hurry and put five thousand feet under her in seven minutes. And when she got upstairs she was ready to talk business at the point of a Vickers fitted on the cowling to fire through the prop while she herself danced around at the rate of 99 miles per hour. She carried nearly twenty gallons of gas and five gallons of oil, and could stay in the air long enough for her to do some real damage to the Germans. And she did just that, for there was many ah Ace that piled up his score behind her guns.

Smaller, But—

She was a lot smaller than Miss Bristol, being only 26 feet across the hips. But don’t think she didn’t get there.

And she had a larger sister that you ought to get acquainted with, just to see how different sisters can be. The sister was Sopwith Camel, Fig. 3, and she was just as tricky as Pup was reliable.

Would she burn you up? And I mean that literally. This is the way it would happen. She was a kind of big Pup who was built to be still faster and more maneuverable. In order to do this she had to sacrifice some of Pup’s good qualities, and she was therefore tricky to fly, and dangerous to land. Her engine, a nine-cylinder Gnome-Monosouppe delighted in setting you on fire.

No Carburetor! No Throttle!

This was because that crazy power plant had no carburetor nor any throttle. The only way you could slow her down once she got started was to cut the ignition from certain of her cylinders.

The result was that the gas vapor would go through those cylinders without burning until it got into the exhaust. And right there the sparks from the other cylinders would ignite it. The result was a nice long sheet of flame pouring out of the exhaust into the slipstream. That made it nice and hot for you if it didn’t ignite the whole ship and leave you well-browned on both sides. Yes, sir, the old gal was hot stuff.

But she was a good old work horse when you got to know her and didn’t mind her spitting fire in your face. And she was armed to the teeth. She had two Vickers guns on the cowling and often a Lewis on the top wing just to balance things off.

Could Do Real Damage

She got a lot better when they took that crazy engine out and put a Clerget in. That sped her up to around 140 miles per hour and made her climb a thousand feet a minute. She could stay in the air two and a half hours a trip, and do real damage.

I suppose I ought to mention a lot of the other gals that helped make that war an exciting one, but there were so many that it is only possible to take a hop, skip and jump down the line and say howdy to a representative few of them.

I ought to tell you about still another Sopwith sister, that we called the one-and-one-half strutter. And I ought to tell you about some of the French ships, and a lot of others. But you’ll have to wait breathlessly for that. Just now, I’ve got a date with a modern little miss that could fly right around a lot of those good old babies, and she’s not armed with Vickers guns either.

Be seeing you.

pen of the Navy’s own Allan R. Bosworth. Bosworth wrote a couple dozen stories with Humpy & Tex over the course of ten years from 1930 through 1939, mostly in the pages of War Aces and War Birds. The stories are centered around the naval air base at Ile Tudy, France. “Humpy” Campbell, a short thickset boatswain’s mate, first class who was prone to be spitting great sopping globs of tabacco juice, was a veteran seaplane pilot who would soon rate two hashmarks—his observer, Tex Malone, boatswain’s mate, second class, was a D.O.W. man fresh from the Texas Panhandle. Everybody marveled at the fact that the latter had made one of the navy’s most difficult ratings almost overnight—but the answer lay in his ability with the omnipresent rope he constantly carried.

pen of the Navy’s own Allan R. Bosworth. Bosworth wrote a couple dozen stories with Humpy & Tex over the course of ten years from 1930 through 1939, mostly in the pages of War Aces and War Birds. The stories are centered around the naval air base at Ile Tudy, France. “Humpy” Campbell, a short thickset boatswain’s mate, first class who was prone to be spitting great sopping globs of tabacco juice, was a veteran seaplane pilot who would soon rate two hashmarks—his observer, Tex Malone, boatswain’s mate, second class, was a D.O.W. man fresh from the Texas Panhandle. Everybody marveled at the fact that the latter had made one of the navy’s most difficult ratings almost overnight—but the answer lay in his ability with the omnipresent rope he constantly carried.

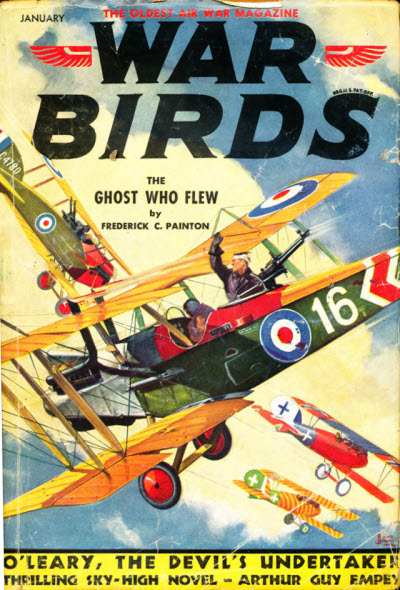

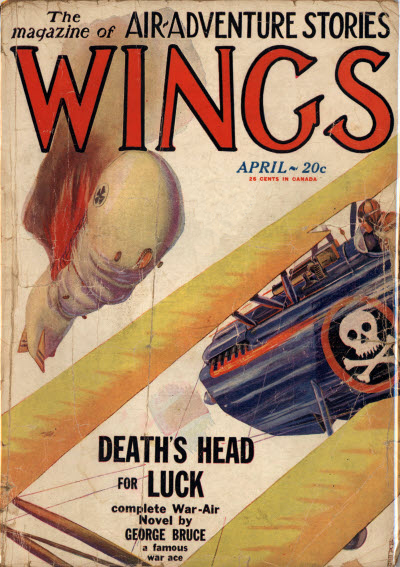

a short story by renowned pulp author Frederick C. Davis. Davis is probably best remembered for his work on Operator 5 where he penned the first 20 stories, as well as the Moon Man series for Ten Detective Aces and several other continuing series for various Popular Publications. He also wrote a number of aviation stories that appeared in Aces, Wings and Air Stories.

a short story by renowned pulp author Frederick C. Davis. Davis is probably best remembered for his work on Operator 5 where he penned the first 20 stories, as well as the Moon Man series for Ten Detective Aces and several other continuing series for various Popular Publications. He also wrote a number of aviation stories that appeared in Aces, Wings and Air Stories.

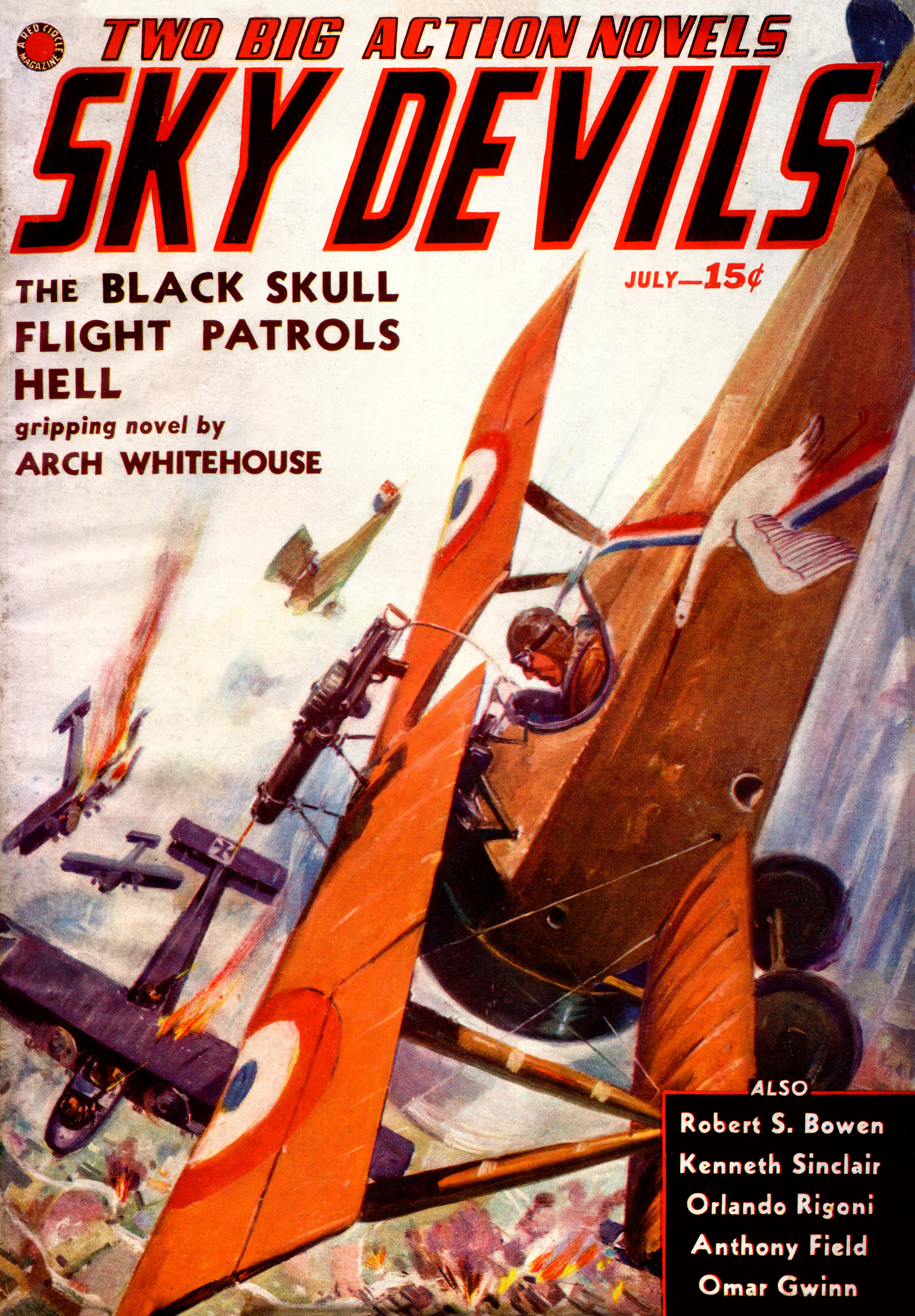

a story from the short-lived Sky Devils magazine by Anthony Field. Anthony Field was a pseudonym used by Anatole Feldman who specialized in gangland fiction—appearing primarily in Harold Hersey’s gang pulps, Gangster Stories, Racketeer Stories, and Gangland Stories. His best-known creation is Chicago gangster Big Nose Serrano. But he also wrote a number of aviation stories including four stories for Sky Devils featuring Quinn’s Black Sheep Squadron—this is the second of those four stories!

a story from the short-lived Sky Devils magazine by Anthony Field. Anthony Field was a pseudonym used by Anatole Feldman who specialized in gangland fiction—appearing primarily in Harold Hersey’s gang pulps, Gangster Stories, Racketeer Stories, and Gangland Stories. His best-known creation is Chicago gangster Big Nose Serrano. But he also wrote a number of aviation stories including four stories for Sky Devils featuring Quinn’s Black Sheep Squadron—this is the second of those four stories!

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

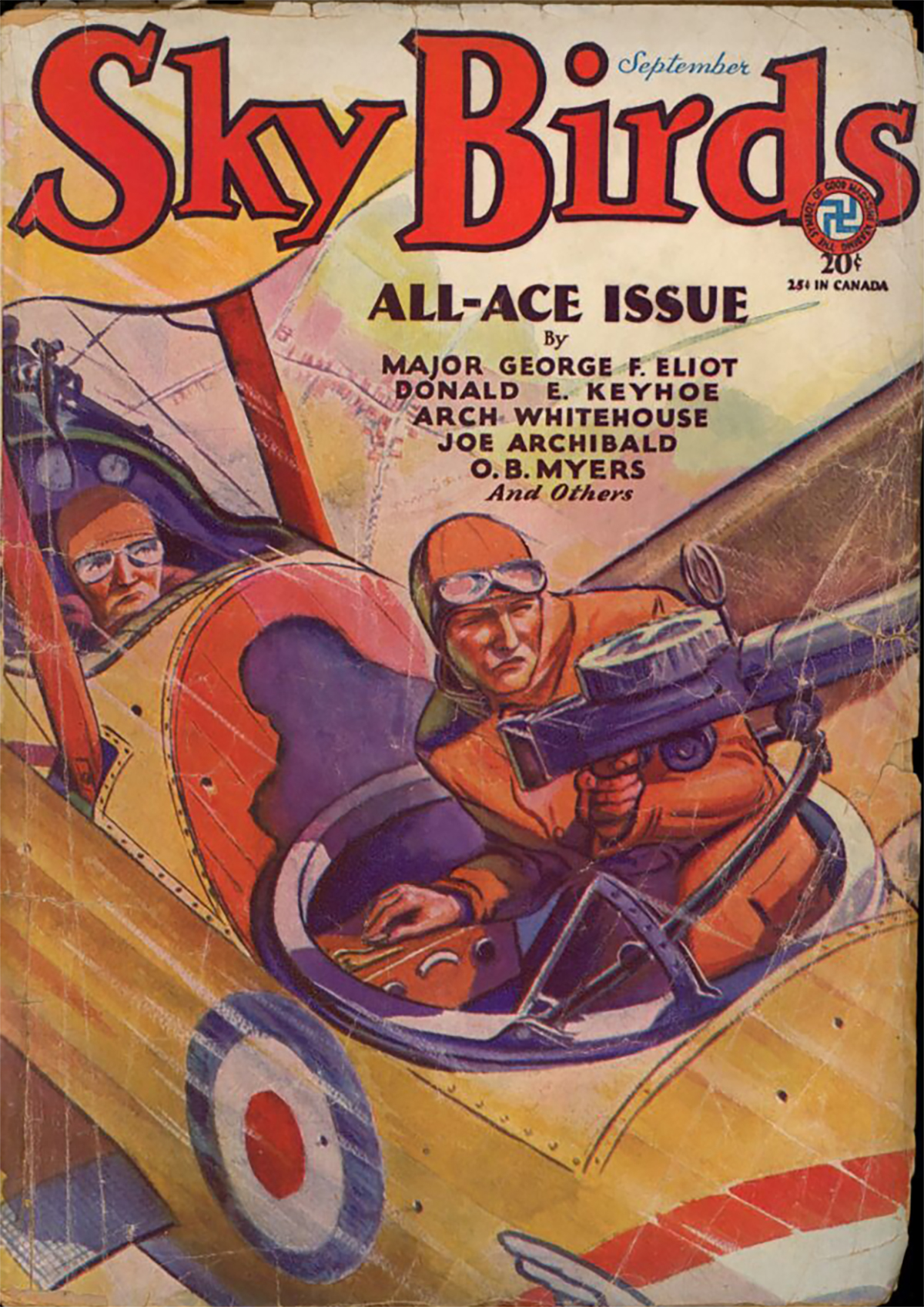

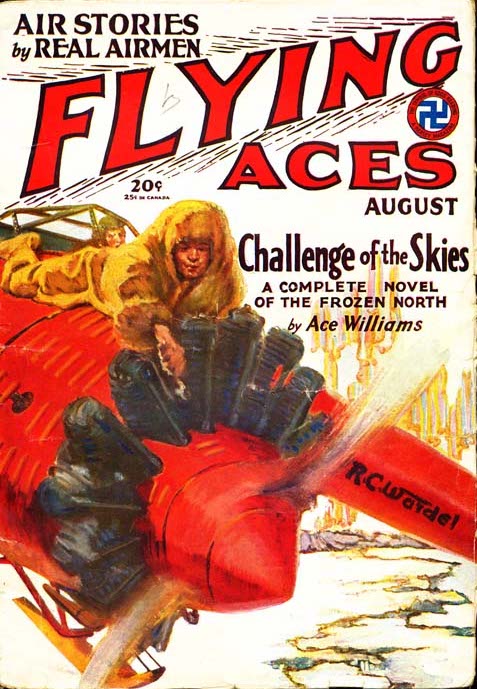

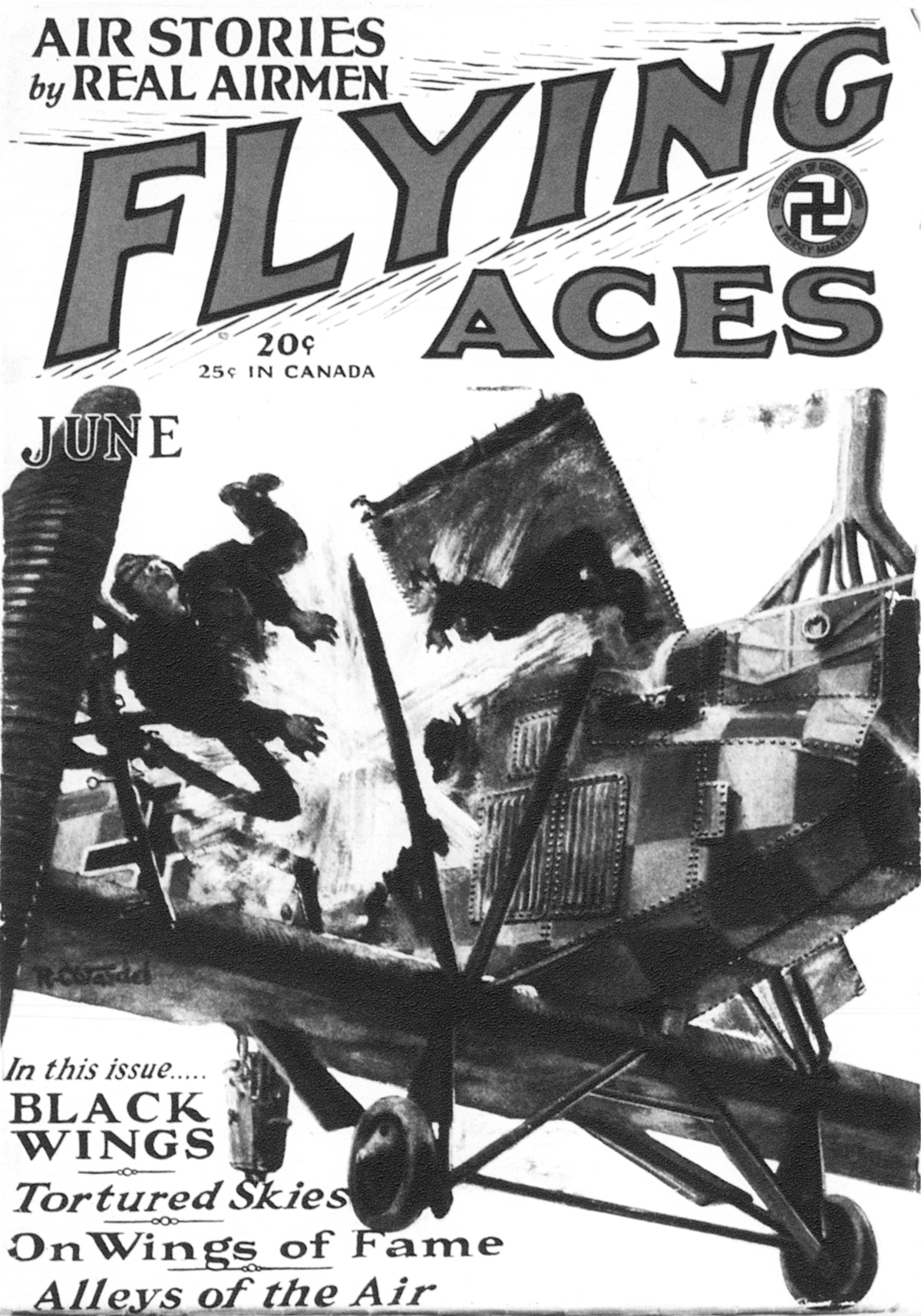

a story by J.D. Rogers, Jr. Rogers is credited with roughly fourteen tales from the pages of Flying Aces, Sky Birds and Sky Aces. “The Yellow Ace” from the August 1929 Flying Aces was his first published tale. In it James Lawrence arrives on the tarmac of the 23rd Squadron R.F.C. with his newly designed fighter plane. In the make-up of this plane was the knowledge and experience of a young man who had played and worked in his father’s aeroplane factory since age permitted. Prompted by zealous patriotic duty he had built this super fighter for his country, a country which the warring nations had far surpassed in the art of building aircraft. Refused a fair demonstration of his plane by a very inexperienced air board, the youth, with his flame of patriotism quenched, turned from his own country to England whose air board was frantic for a plane fast enough and maneuverable enough to successfully combat the German demons who had held the air supremacy through the war.

a story by J.D. Rogers, Jr. Rogers is credited with roughly fourteen tales from the pages of Flying Aces, Sky Birds and Sky Aces. “The Yellow Ace” from the August 1929 Flying Aces was his first published tale. In it James Lawrence arrives on the tarmac of the 23rd Squadron R.F.C. with his newly designed fighter plane. In the make-up of this plane was the knowledge and experience of a young man who had played and worked in his father’s aeroplane factory since age permitted. Prompted by zealous patriotic duty he had built this super fighter for his country, a country which the warring nations had far surpassed in the art of building aircraft. Refused a fair demonstration of his plane by a very inexperienced air board, the youth, with his flame of patriotism quenched, turned from his own country to England whose air board was frantic for a plane fast enough and maneuverable enough to successfully combat the German demons who had held the air supremacy through the war.

another story by Alfred Hall Stark. Stark wrote a dozen or so stories for the pulps, frequently dealing with aviation, in the late twenties and early thirties before building a reputation for writing well-researched, fact-based articles for The Reader’s Digest, Popular Science, Saturday Evening Post and others.

another story by Alfred Hall Stark. Stark wrote a dozen or so stories for the pulps, frequently dealing with aviation, in the late twenties and early thirties before building a reputation for writing well-researched, fact-based articles for The Reader’s Digest, Popular Science, Saturday Evening Post and others.

a story by Alfred Hall Stark. Stark wrote a dozen or so stories for the pulps, frequently dealing with aviation, in the late twenties and early thirties. Stark was a pseudonym for Afred Halle Sinks. Sinks was a native of Ohio, who won his reportorial spurs in New York before heading to Porto Rico to work on the Porto Rico Progress published in San Juan. When sinks returned to the US, he was a staff writer for Popular Science and The Reader’s Digest building a reputation for writing well-researched, fact-based articles for those publications as well as others and newspapers.

a story by Alfred Hall Stark. Stark wrote a dozen or so stories for the pulps, frequently dealing with aviation, in the late twenties and early thirties. Stark was a pseudonym for Afred Halle Sinks. Sinks was a native of Ohio, who won his reportorial spurs in New York before heading to Porto Rico to work on the Porto Rico Progress published in San Juan. When sinks returned to the US, he was a staff writer for Popular Science and The Reader’s Digest building a reputation for writing well-researched, fact-based articles for those publications as well as others and newspapers. In a brief biographical paragraph from an article in 1963, Alfred Halle Sinks was said to be living in Philadelphia and responsible for the public information program that launched Bucks County’s open space conservation program. By that time he had been editor of the Bucks County Traveler, as well as a staff writer for Popular Science and Reader’s Digest, and had contributed articles to the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Ladies Home Journal, and other leading national magazines.

In a brief biographical paragraph from an article in 1963, Alfred Halle Sinks was said to be living in Philadelphia and responsible for the public information program that launched Bucks County’s open space conservation program. By that time he had been editor of the Bucks County Traveler, as well as a staff writer for Popular Science and Reader’s Digest, and had contributed articles to the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Ladies Home Journal, and other leading national magazines.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.