BACK in 2015 we posted a bunch of  correspondence between Henry Steeger, Robert J. Hogan, and Bob Swift that Pulp Historian Don Hutchison handed us at PulpFest. The letters with Bob Swift concerned a feature article he was writing for the Miami Herald Sunday Magazine. Although Don had given us the letters, the package did not include the Miami Herald Sunday Magazine feature story. But thanks to Newspapers.com, we have finally got a copy of it to share with our readers.

correspondence between Henry Steeger, Robert J. Hogan, and Bob Swift that Pulp Historian Don Hutchison handed us at PulpFest. The letters with Bob Swift concerned a feature article he was writing for the Miami Herald Sunday Magazine. Although Don had given us the letters, the package did not include the Miami Herald Sunday Magazine feature story. But thanks to Newspapers.com, we have finally got a copy of it to share with our readers.

Without further ado, here is Bob Swift’s feature:

G-8: Spy King of the Pulps

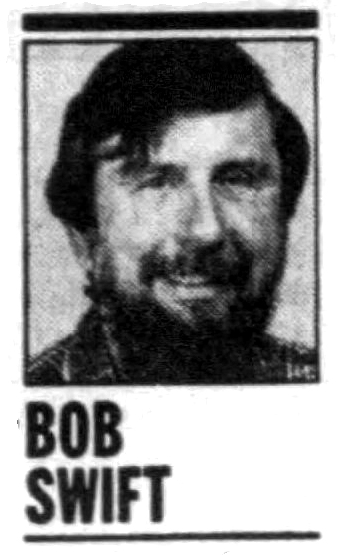

by BOB SWIFT | The Miami Herald, Miami, Florida • 8 July 1962

Remember before TV, when the lurid pulp magazine was the boy’s best friend? Remember Bob Hogan’s fabulous heroes, G-8 and His Battle Aces?

|

Debonair G-8, as drawn by John Fleming Gould, for the pulp magazine series that bugged the eyes of young readers for 11 years. G-8, created by Robert J. Hogan, was a master spy, makeup artist, ace pilot, a hero in the tradition of the dime novels.

|

ENTER the Depression era small town boy, bicycle-borne, legs pumping, frayed and faded school books bouncing in the bike basket, dime burning the clenched fist like a nugget of lye.

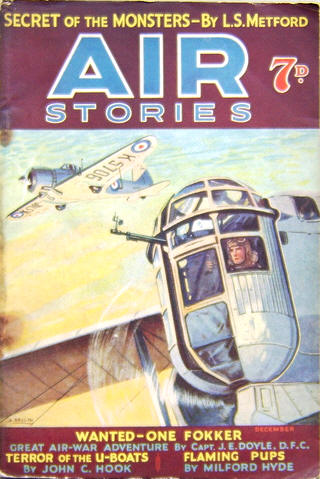

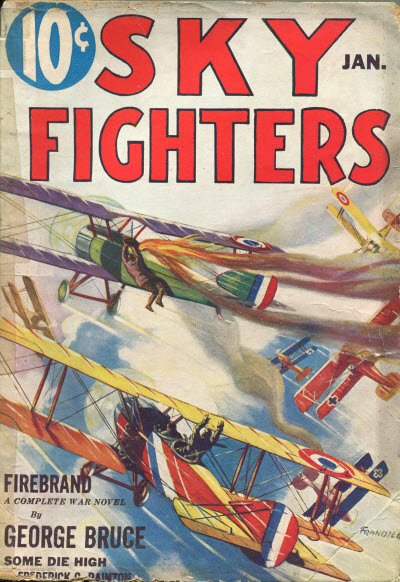

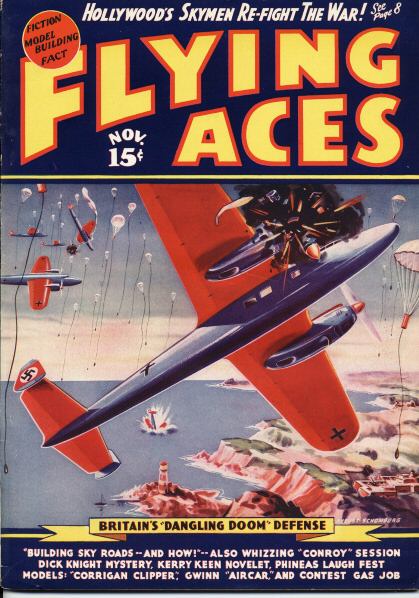

Past the candy store with its dubble-bubble. Past the movie with Hoot Gibson. Past the drug store and the root beer float. Here. The news stand. Padded clatter of Keds on the wooden floor. There. Row upon lurid row, garish and glorious, the pulp magazines of the 1930’s.

Were you a fan, back In those beautiful days when the pulp was king? It was before TV (what you did, you listened to I Love a Mystery, the Green Hornet and Jack Armstrong on the radios). And what you did, you read the pulps.

There was Doc Savage, the man of bronze; the Shadow, whose flaming automatics piled crooks like cordwood; Nick Carter, the master detective; the Spider, soaring on a silken web; Wild West Weekly and Western Story Magazine.

But what really made that school literature book a volume of tepid pap was a brassy book called G-8 and His Battle Aces, a seven by 10 inch pulp magazine whose contents palsied the hand, dried the mouth, popped the young eyeball and packed a bigger kick than a surreptitious Domino cigaret.

America’s Master Spy. who could pilot a Spad pursuit plane in circles around any World War I ace. Master of makeup, crack shot, superb physical specimen, noble and true, ruthless to the enemy. That was G-8 as created by Robert J. Hogan, one of the most prolific pulp writers of his day.

Robert J Hogan wasn’t just the communal pen name for some stable of writers who took turns writing some of the pulps of that era.

Hogan was—and is—Hogan. Today. Bob Hogan lives in Coral Gables, 829 Granada Grove Ct.

He fondly remembers his pulp hero.

“I love G-8.” says Hogan, a spare, balding man of 64. “G-8 was good to me, supported me for 11 years, built our summer home in New Jersey.”

Bob, a preacher’s son from Buskirk, NY, learned to fly in World War I, demonstrated private planes after that, found himself almost penniless when his company closed in the Depression’s early day. He happened to buy a pulp aviation magazine, snorted, “Hell. I can write better than that.” and did so. He sold his first story to Wings Magazine for $65, was off on a writing career.

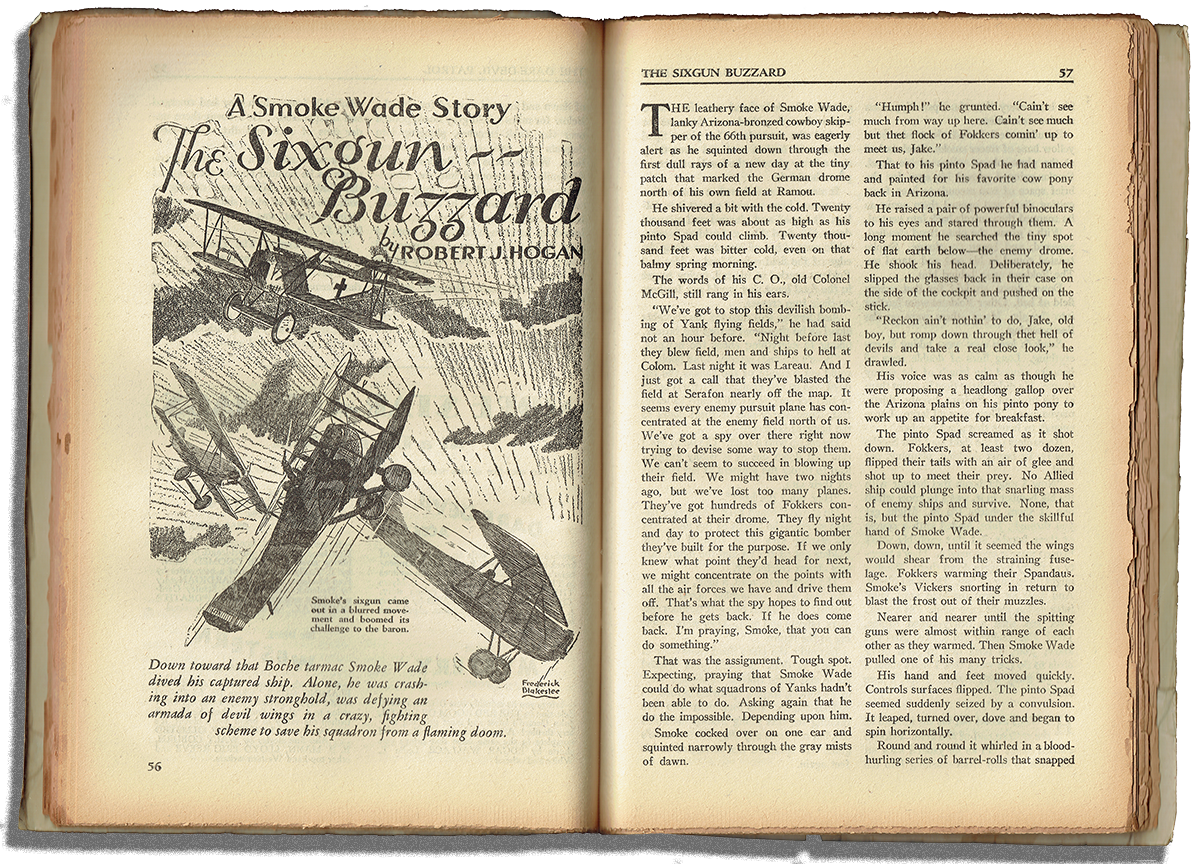

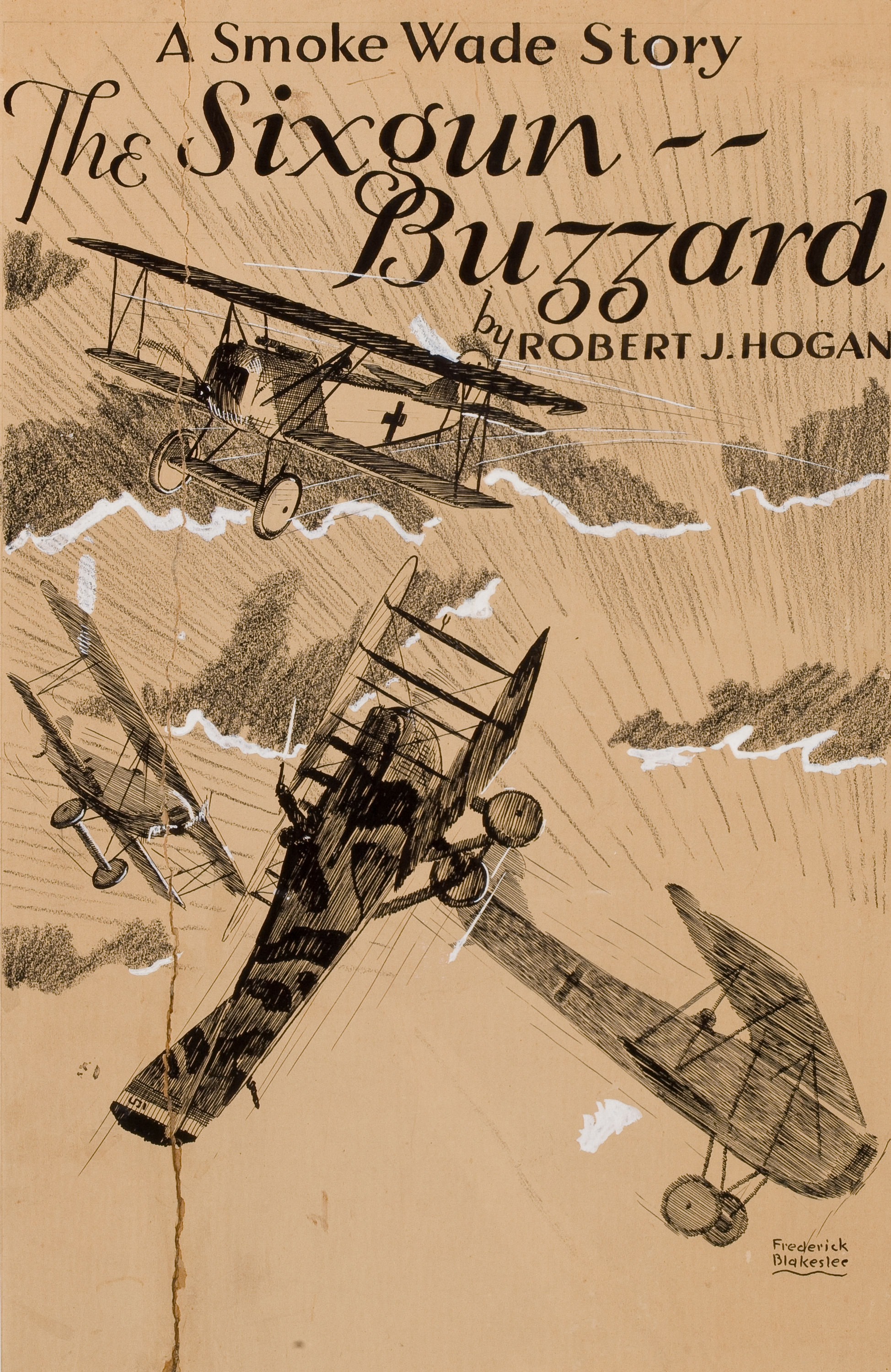

“Does anyone remember a series called The Red Falcon?†wonders Hogan. “Or the Smoke Wade stories in Dare-Devil Aces magazine?”

But other pulp fiction publishers began turning to novel length stories featuring the same character each month . . . the Shadow, Doc Savage. Hogan’s chore: Dream up an air hero. Driving home from his publisher’s office one day in 1933. Hogan’s racing brain came up with G-8 and His Battle Aces.

There was G-8 himself, the Master Spy. There were his sidekicks, little Nippy Weston (”Hey, you dumb ox!”) and burly Bull Martin (”Holy herring!â€) and Battle, their English butler.

That first novel was called The Bat Staffel, the latter being a German word meaning squadron. Then came the whole great series that ran from 1933 to 1944, a series of novels whose titles had a certain zing, such as: “Death Rides the Ceiling,†“Skies of Yellow Death,” “Patrol of the Mad,†“Scourge of the Steel Mask,†“Wings of the Juggernaut,†“Vultures Of the Purple Death,†“The Death Monsters,†“Wings of Invisible Doom,†or “The Staffel of Beasts.”

Imagination unlimited was the rule of the pulp magazines and G-8 fought monsters with tentacles, men with beast brains, flying zombies, marching skeletons, mad scientists, mysterious gas, flying bombs, monster tanks with spiked treads and flame throwers, armored dirigibles, magnetic rays.

Particular villains plagued G-8 for years. One was the horrifying Steel Mask. Another was the yellow peril, Dr. Chu Lung. But the adversary who gave G-8 the creeps the longest was the wretched evil genius, Herr Doktor Krueger:

“Emaciated beyond description . . . shrunken, half-paralyzed body . . . head huge at the top . . . ‘Ha, ha.’ cackled the little fiend doctor . . . a cackling, high-pitched laugh left the ugly mouth of Herr Doktor Krueger …”

And talk about television blood and mayhem! G-8 beat today’s fare by a gory mile. The Master Spy never got through an issue without shooting, stabbing or otherwise disposing of a dozen or so enemy pilots, soldiers, guards, spies, madmen or monsters.

How about this scene from “The Sword Staffel” of June, 1935:

“There was a sword covered with blood. It measured at least six feet in length . . . the handle was large and gripping it tightly was a ponderous, human arm. The flesh was seared like a half-broiled steak . . . it was severed at the shoulder as though it had been torn off.”

Whew! Heady stuff. And we loved it.

In one novel the mad scientists boiled bodies in cauldrons, sent zombie-like skeletons marching against the Allies.

“My editor became nauseated.” says Bob Hogan with some relish. “Had to leave his desk.”

There was “Wings of the Glacier Men,” wherein the Germans found a whole army of Vikings frozen in a glacier, brought them to life, used them as hideous soldiers.

Aerial combat played a big part in G-8’s adventures, too:

“G-8 was sure his bullets had spattered into the lead pilot’s body, but he was still flying. Instantly, G-8’s brain flashed to the time when Germany had sent over the gorilla men who could not be killed. Were these men wearing bullet proof armor, too? Tac-tac-tac! Spandeau bullets snapped past his head . . .â€

|

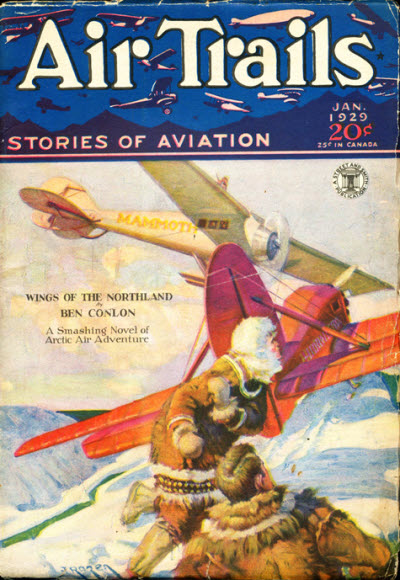

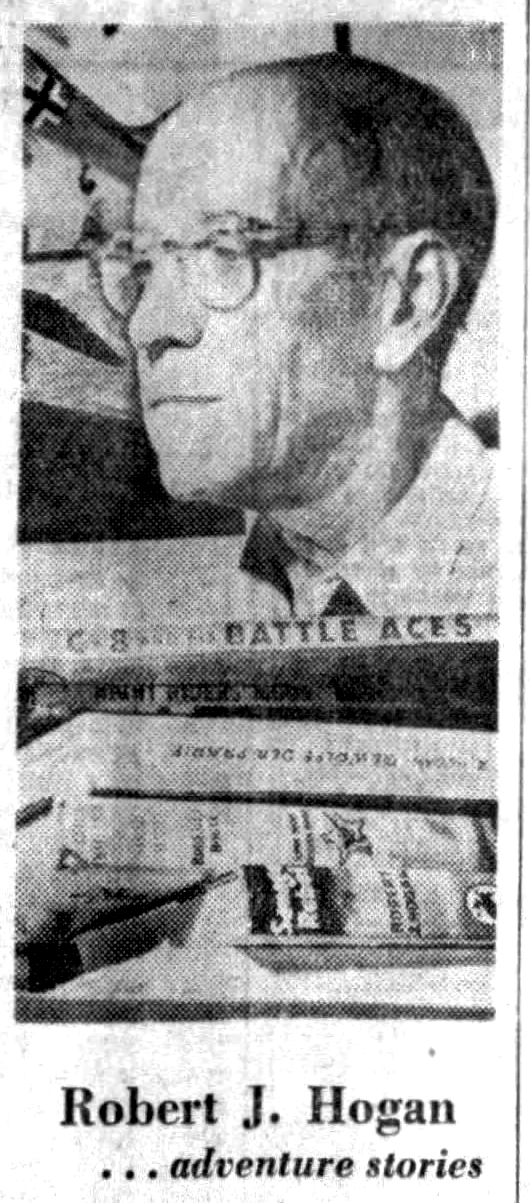

Author Bob Hogan, who turned out 200,000 pulp fiction words a month in the late 1930’s, is still writing on the typewriter that pounded out the first G-8 story. Hogan and his wife live in Coral Gables in the winter. New Jersey in the summer. The books are all by Hogan, some in German translations. Painting is an illustration for one of his Worid War II flying stories.

|

Hogan wasted no time inventing complicated names for his foreign characters. He glibly tossed off handles like Monsieur Chapeau, Herr Schmaltz and Herr Butscher, injected a few ach du liebers and violas and went merrily on with the plot.

There was even a female spy with the lovely name of R-1. She was what you might call the love interest if you stretched a point, although romance in a G-8 novel was tailored to the tastes of the 14-year-old, with the result that any cuddling between G-8 and R-1 was roughly akin to that between Roy Rogers and Trigger.

No matter. When that G-8 novel was finished, the short stories digested and the G-8 Club news read (sometimes all this occurred by flashlight under the covers), it was time to begin the impatient waiting until next month’s issue.

Even the ads were wonderful. Johnson Smith & Co. offered courses in Ju Jitsu, Whoopee Cushions for a quarter. French Photo Rings and Boys. Boys, Learn to Throw Your Voice. Charles Atlas stared from the page and sneered. “You can have a body like mine.” You were entreated to buy yeast for those pesky pimples. And for the more mature reader, it is hoped, there was the ad for Crab Orchard Whisky, guaranteed a mellow 18 months old.

When G-8 was in his prime. Bob Hogan turned out 200,000 words a month, pacing his Sparta, N.J. home with the radio full blast, bouncing a rubber ball on the floor, dictating to two secretaries at once.

At one incredible time, Hogan was writing the G-8 series, a cops and robbers series called The Secret Six and a Chinese menace series called Wu Fang, each calling for a 60,000 word novel a month plus enough short stories to fill the back of each magazine. In addition, he ran the fan club (”Hello, gang, this is G-8 speaking.”).

A Readers Digest article called him one of the world’s most prolific writers.

Hogan’s orders were to turn out the copy. Don’t edit it, said his publisher, don’t rewrite it, don’t even read it. Just turn it out and mail it. And that’s just what Hogan did.

“I have yet to read a G-8 story,” he says with wry curiosity. “Wonder if they were any good?”

“G-8 was aimed at boys about 14 years old, but I had fans ail ages and all over the world. One was president of a street car company in Scotland. Another was a Bengal Lancer in India.’

Hogan still gets letters from old fans who wish their own kids could read G-8. But alas, that’s almost impossible. A mint copy which once sold for 10 cents might bring $50 today, if you could find one.

Hogan himself has a complete set of G-8 at his lodge in New Jersey, “The House That G-8 Built.” There, too, are Hogan’s mementos: airplane struts serving as curtain rods, engine parts for andirons, bomb casings for lamps.

G-8 appeared in about 1OO novels, finally died in World War II.

“Production costs killed the pulps.” sighs Hogan. “And, of course, in the day of the B-29 and radar, the demand for stories about Spads and the Kaiser sort of wore itself out.”

G-8 buried and mourned, Hogan turned to slick magazines, westerns, juveniles, TV. One of westerns became a movie, The Stand at Apache River. A juvenile novel, Howl at the Moon was considered a classic boy-dog story. Many of his books have been translated into foreign languages.

Hogan has slowed a bit lately. He and his wife Betty, winter in Coral Gables, summer in New Jersey. But the typewriter still clatters though the pace has relaxed. What Hogan would like to do now is re-issue G-8 in some form or other, for nostalgia fans maybe make G-8 a TV show.

We can hope so. In the meantime, go back in spirit to the hot summer day, the ceiling fan turning in the news stand, the rows of lurid covers, the swap of hand-heated coin for shiny book, the long walk home with open magazine, palpitating heart and great risk to life and limb.

Turn the pages slowly. Savor the deathless prose:

‘ . . . he knew a fiend had turned his pals into a Squadron of Living Death. He knew that the remedy lay in a will to fight and fight and fight . . . a low, vibrant chuckle left the lips of G-8 . . . the Master Spy shot his fist up in a signal to the Battle Aces . . . the Spad howled up in a steep climb . . . Fokkers thundered from the sky . . . tac-tac-tac! the machine guns clattered a hymn of hate . . . tac-tac-tac! tac-tac-tac!

ancestors whose reputations had to be upheld. The Nieuport line was of the French aristocracy of war planes. The early Nieuport scouts were named “avions de chasse.†They were to the world war what the cavaliers clad in shining armour riding prancing Arabian horses were to the Middle Ages. The end of the war saw the Nieuport 28C1, a single-seater fighter, which made those American pilots speak of this plane with affection almost twenty years after the war.

ancestors whose reputations had to be upheld. The Nieuport line was of the French aristocracy of war planes. The early Nieuport scouts were named “avions de chasse.†They were to the world war what the cavaliers clad in shining armour riding prancing Arabian horses were to the Middle Ages. The end of the war saw the Nieuport 28C1, a single-seater fighter, which made those American pilots speak of this plane with affection almost twenty years after the war.

a story from the prolific T.W. Ford. Ford wrote hundreds of stories for the pages of the pulps—westerns, detective, sports and aviation—but best known for his westerns featuring the Silver Kid.

a story from the prolific T.W. Ford. Ford wrote hundreds of stories for the pages of the pulps—westerns, detective, sports and aviation—but best known for his westerns featuring the Silver Kid.

another of

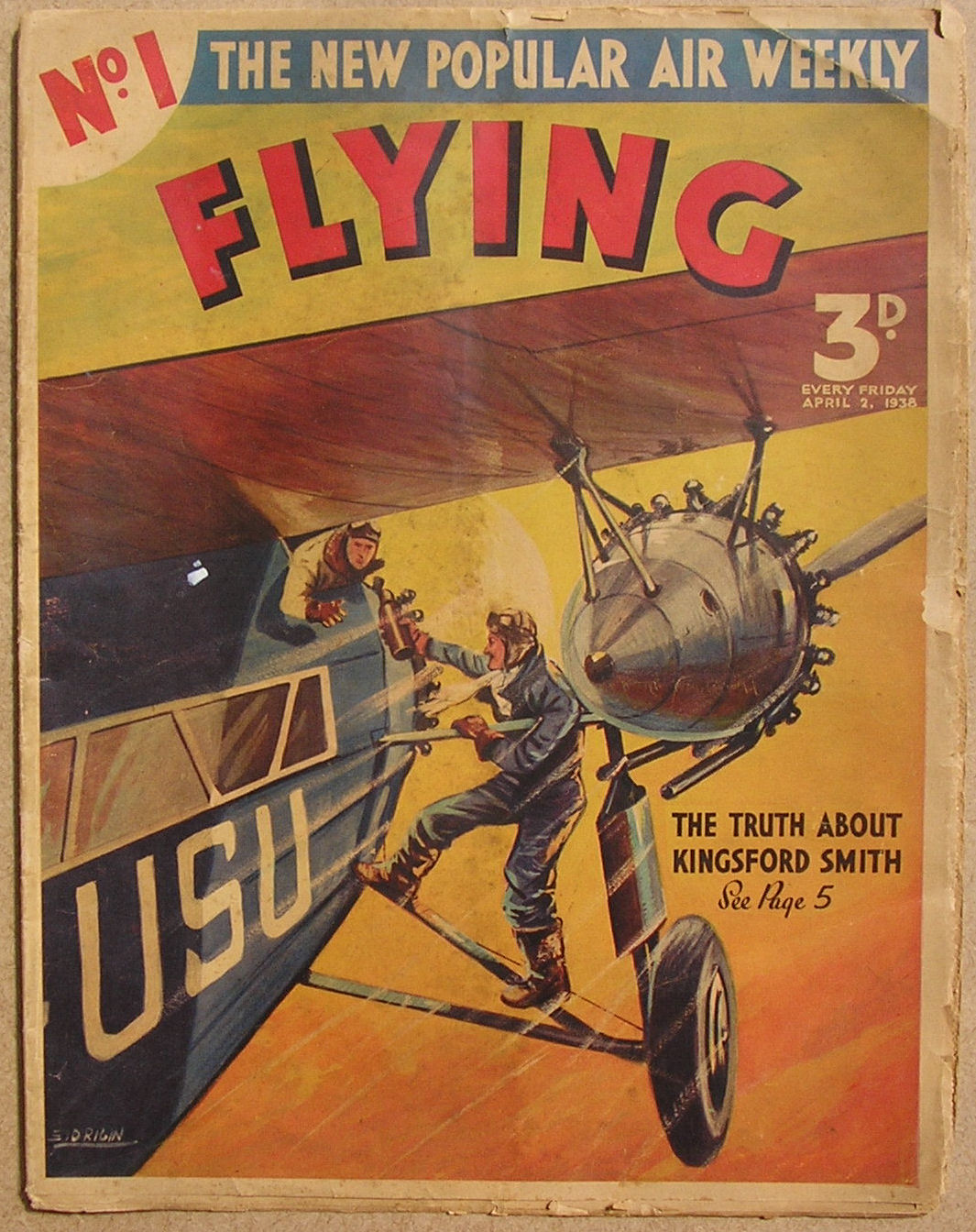

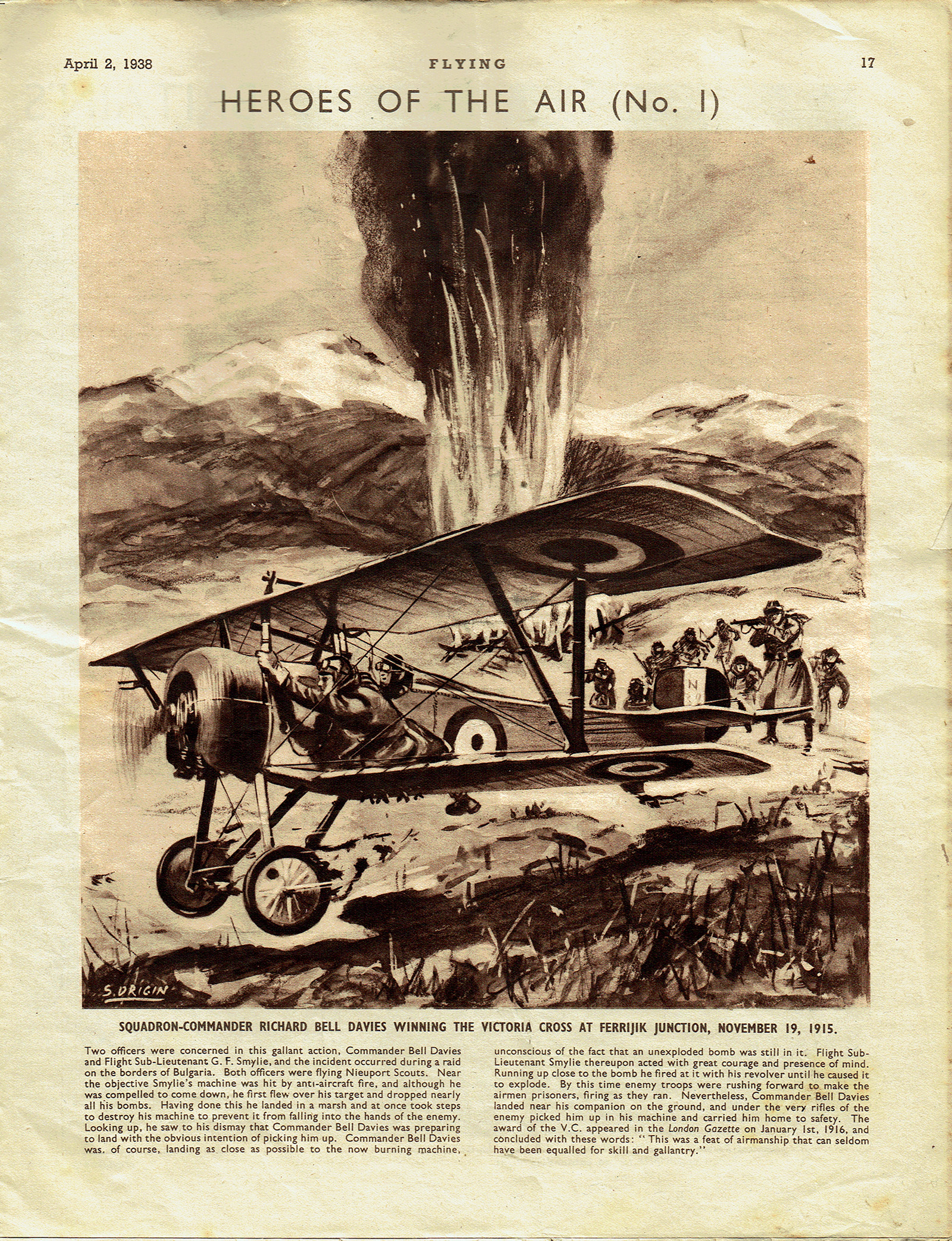

another of  weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

a story from the pen of British Ace,

a story from the pen of British Ace,  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

another gripping tale from the prolific pen of

another gripping tale from the prolific pen of  That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

an early story from the prolific pen of Mr. Robert J. Hogan—the author of

an early story from the prolific pen of Mr. Robert J. Hogan—the author of  but they just weren’t on a literary level with the pulps, which came in all types: detective, science-fiction, westerns, etc. One of the most popular types was the air-adventure, of which there were scores. Of those, the one that really made a kid’s eyeballs pop was G-8 and His Battle Aces, which packed a bigger kick than a surreptitious puff on a Domino cigarette.

but they just weren’t on a literary level with the pulps, which came in all types: detective, science-fiction, westerns, etc. One of the most popular types was the air-adventure, of which there were scores. Of those, the one that really made a kid’s eyeballs pop was G-8 and His Battle Aces, which packed a bigger kick than a surreptitious puff on a Domino cigarette. 829 Granada Grove Ct., Coral Gables, one of the most prolific pulp writers of his day, died Tuesday at the age of 66.

829 Granada Grove Ct., Coral Gables, one of the most prolific pulp writers of his day, died Tuesday at the age of 66.