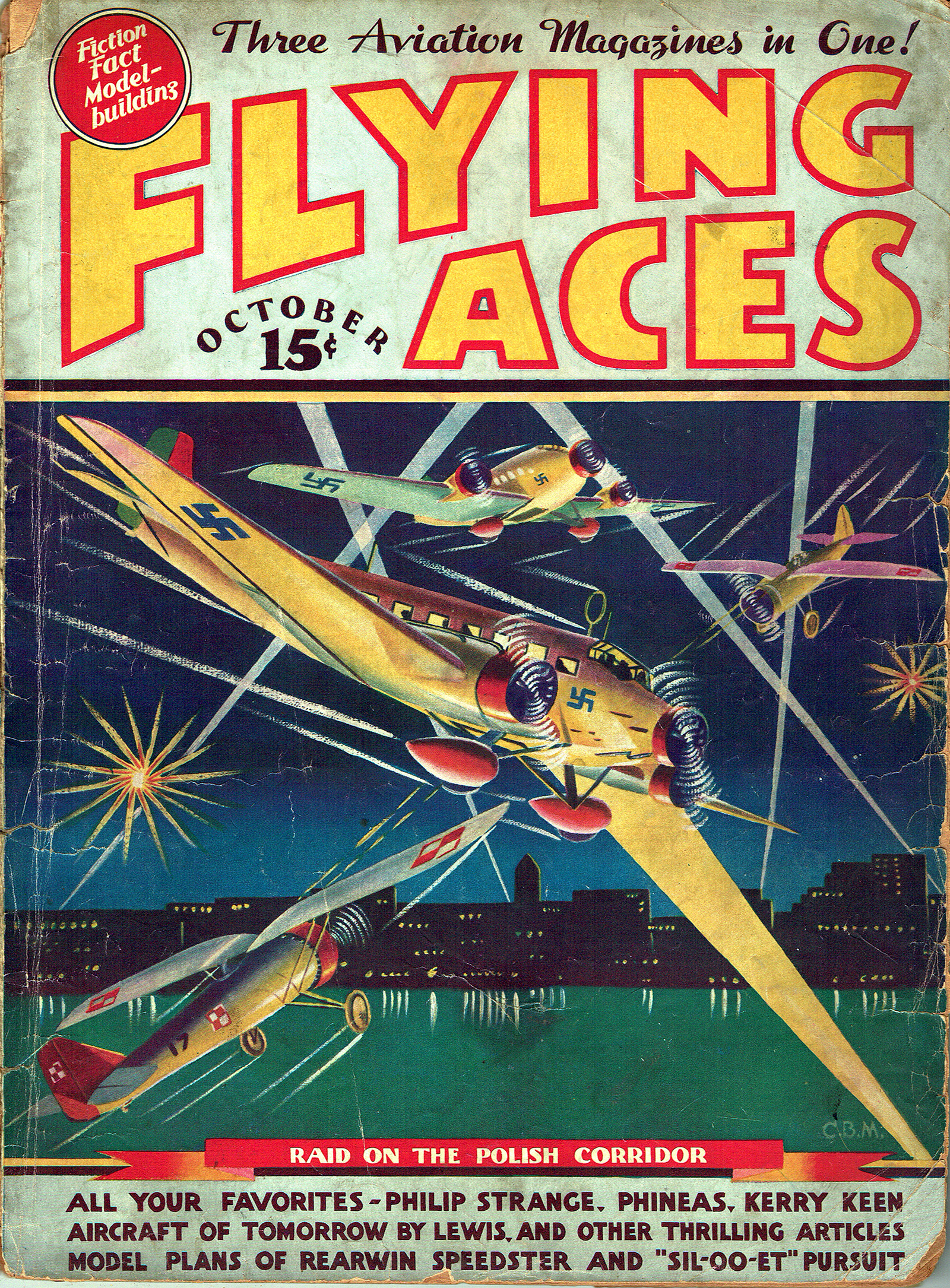

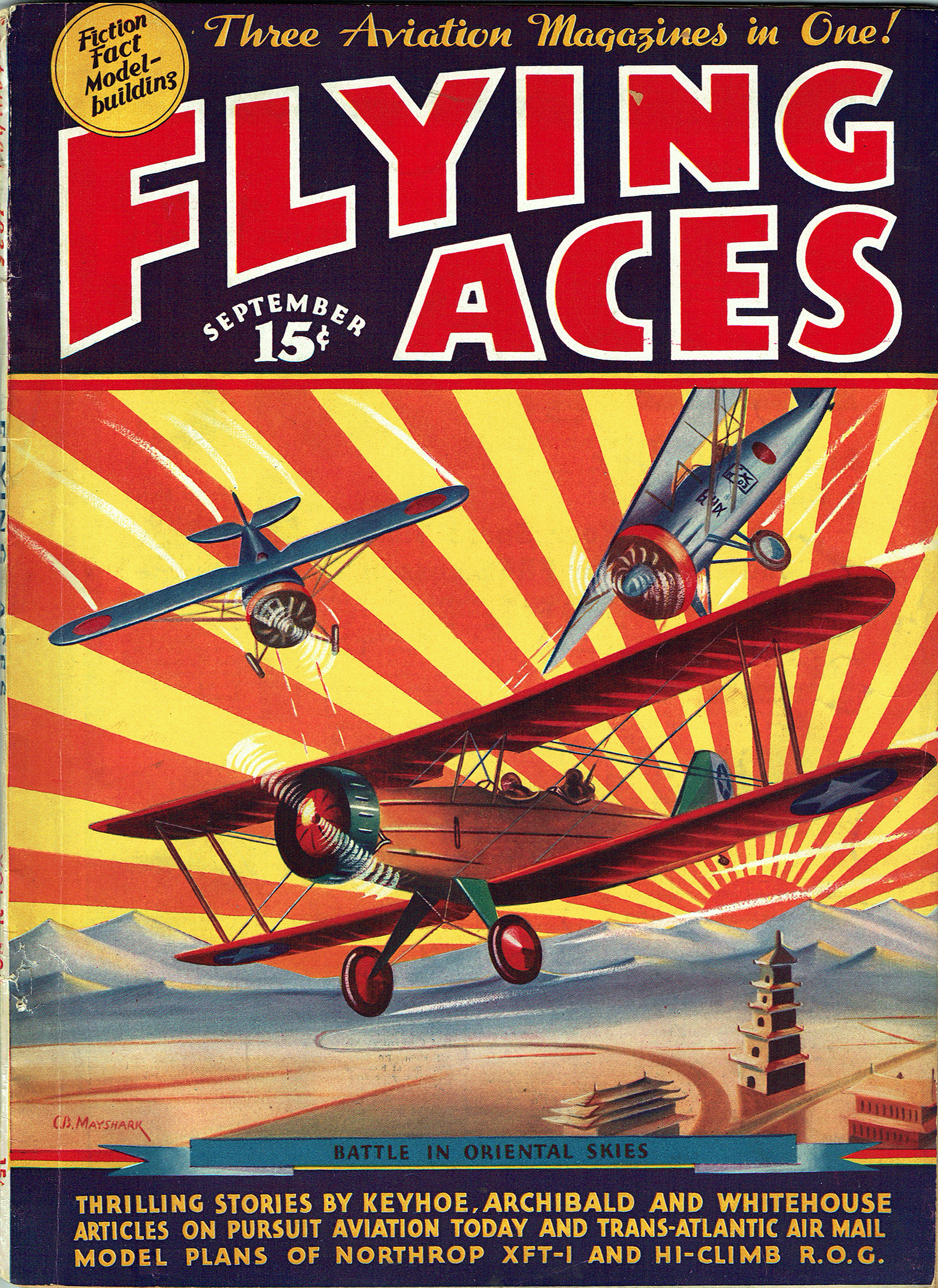

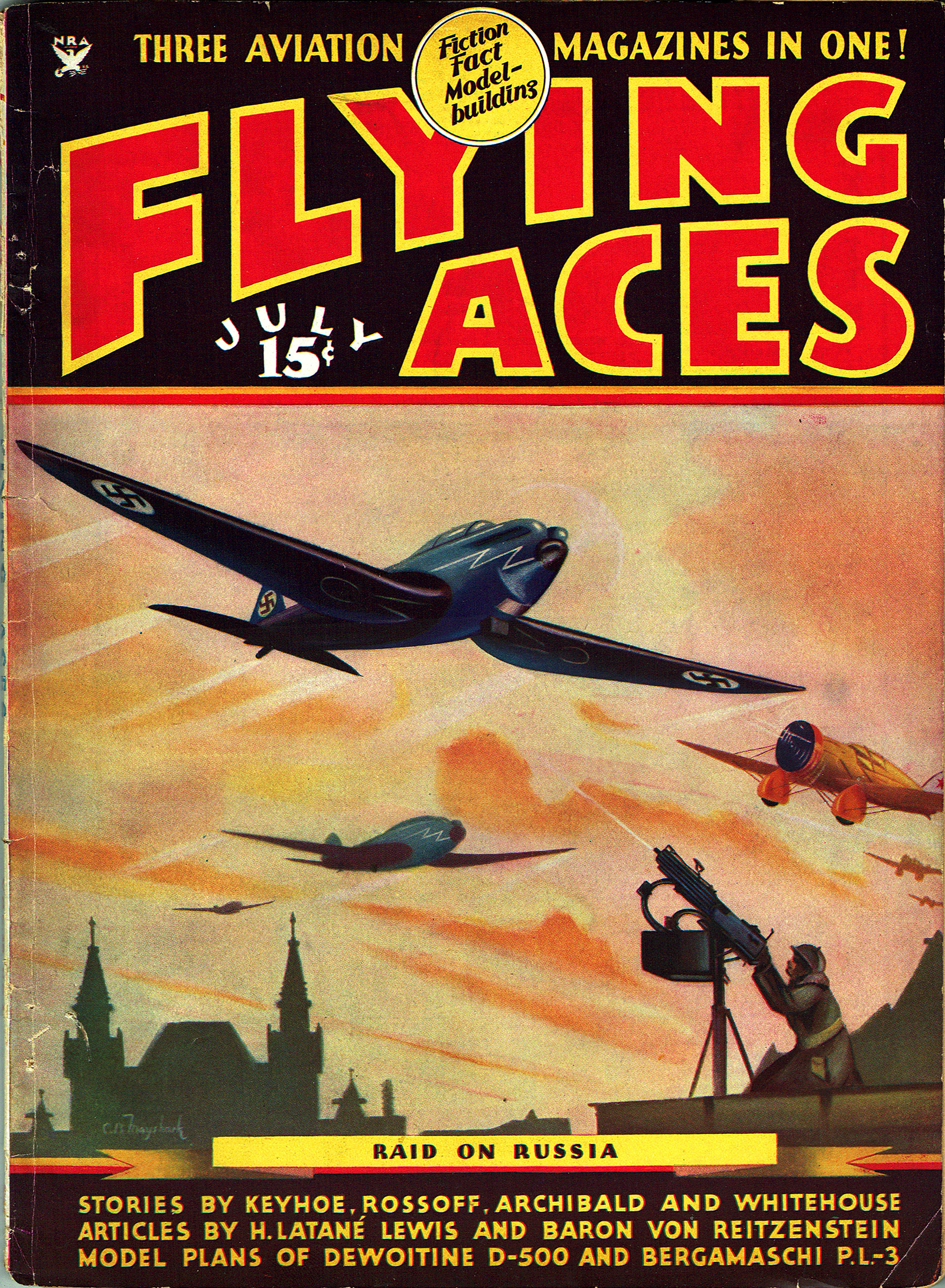

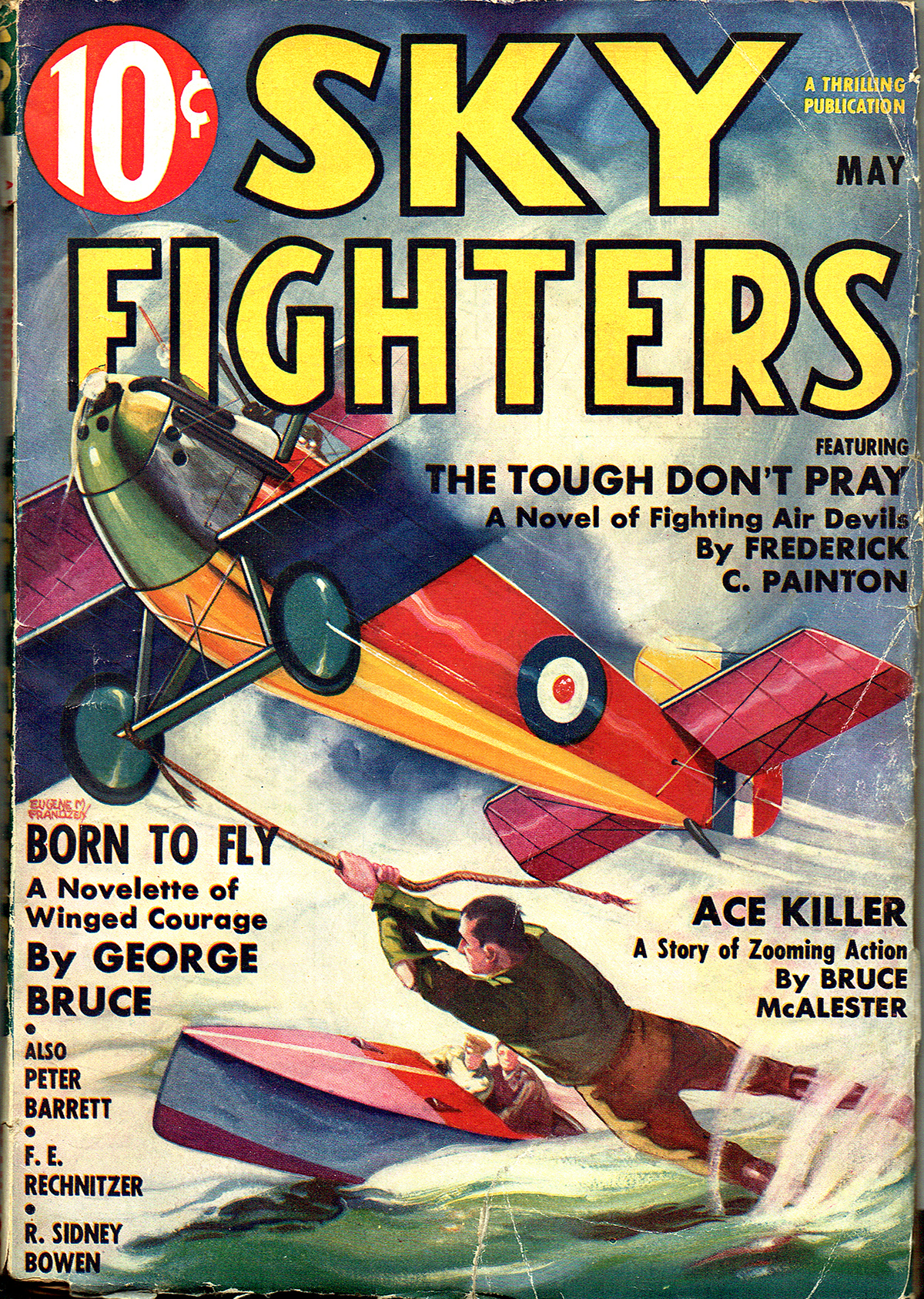

“Sky Fighters, November 1937″ by Eugene M. Frandzen

Eugene M. Frandzen painted the covers of Sky Fighters from its first issue in 1932 until he moved on from the pulps in 1939. At this point in the run, the covers were about the planes featured on the cover more than the story depicted. On the November 1937 cover, It’s the deadly Gotha!

The Ships on the Cover

GOTHA! An ominous word during the World War days. Gothas over London raining steel-cased loads of high explosive, inflammable liquid, shrapnel. Gothas over Paris dropping bombs and hundreds of pounds of propaganda leaflets proclaiming: “We are at your gates. Surrender!†No wonder that millions of civilians far behind the actual fighting lines shuddered in terror as warning sirens blared their screeching blasts across the roof tops.

GOTHA! An ominous word during the World War days. Gothas over London raining steel-cased loads of high explosive, inflammable liquid, shrapnel. Gothas over Paris dropping bombs and hundreds of pounds of propaganda leaflets proclaiming: “We are at your gates. Surrender!†No wonder that millions of civilians far behind the actual fighting lines shuddered in terror as warning sirens blared their screeching blasts across the roof tops.

Defending planes seemed helpless against huge raiders whose pilots were so bold that they flew over England in daylight.

Shattering Morale

The Germans knew that more actual harm could be done to the Allied cause by shattering the nerves and morale of the great masses of humanity in the crowded cities than battering holes in the Allies’ front lines. It brought the war right into the living room. Even if casualties were comparatively small, the damage done to buildings and streets vividly kept before a jittery populace’s eyes the devastating results of war, kept their sleep broken, kept them forever wondering where the next bomb would strike, if they would be torn, bleeding things smashed and broken in an avalanche of falling masonry and flying hunks of smoking steel fragments.

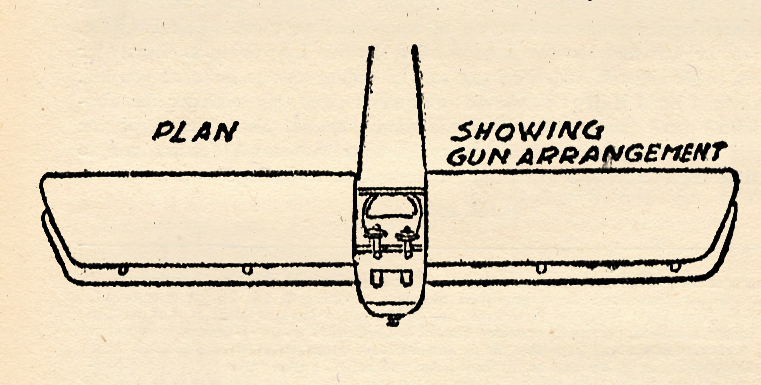

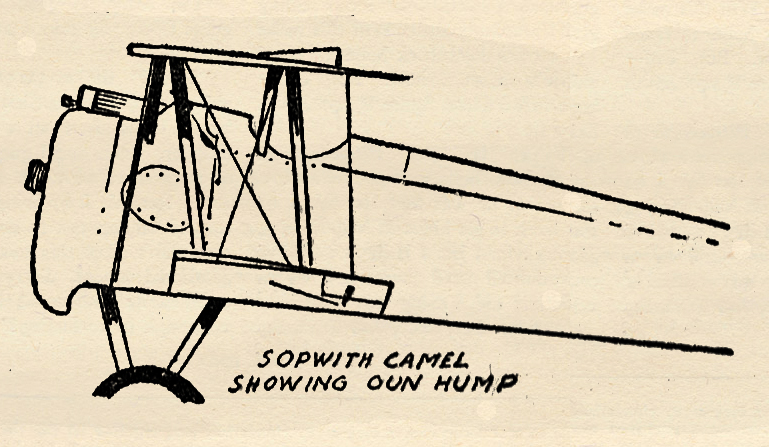

The name Gotha came from the first word of the manufacturing company’s name, Gothaer Waggonfabrik A. G. Aircraft Department. Their most famous job was the twin-engined pusher carrying a pilot, a front gunner and a rear gunner. This ship is pictured on the cover.

Successful Fighting Ships

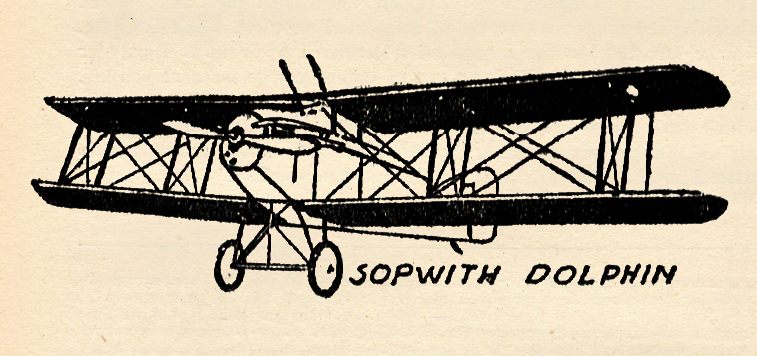

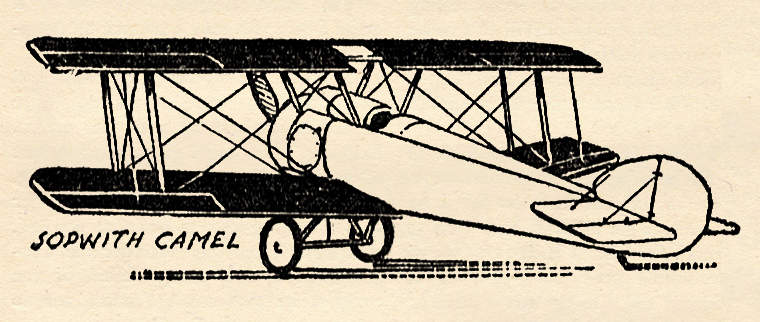

The Morane-Saulnier Company rendered great service to the Allies by producing a series of highly successful fighting ships. The Parasol or high wing monoplanes were their specialty, but they made biplanes and early in the fracas put out different types of wire-braced low-winged jobs which although fragile things were speedy and dependable except in a hard dive.

Roland Garros, the famous French airman, used one of these ships in his experiments with the front gun firing through the propeller arc. This was not a synchronized firing gun, that is, the gun was not mechanically timed to fire so it missed the propeller blade. Any machine-gun could be used and was fired by hand. The slugs bashed against the whirling prop nearly as often as they slipped through but no appreciable harm was done as a pair of steel deflecting flanges were bolted around the propeller blades just outside of the hub. When the bullets hit the gentle angle of the flanges they were deflected harmlessly into space. But those bullets which got through were just as deadly and accurate as bullets from later synchronized guns.

The Gotha crew felt absolutely safe from this wasplike single seater as it rushed up at them. They feared it just as much as a great Dane would a yipping poodle. And just because of their lack of respect they were caught flat-footed. It was unheard of that a tractor plane could shoot forward. The front gunner of the Gotha nonchalantly started to swing his gun forward toward the tiny plane.

Death Dive

He never knew what hit him. He swayed, lost his balance and fell over the side. The pilot became panic stricken, started to release his bombs to gain altitude and possibly crash a missile through the spindly wings of the French plane. The back gunner forgot himself and fired through his left hand propeller in hopes of hitting the foe. But that propeller had no deflecting flanges. A slug tore into the laminated, whirling blade. It splintered into bits.

The Gotha shuddered, gently listed and then lurched into its death dive. Germany’s threat collapsed. Millions of people behind the lines threw back their shoulders and went confidently again at that very important job of winning the war.

Sky Fighters, November 1937 by Eugene M. Frandzen

(The Ships on The Cover Page)