TODAY we bring you an article about the Independent Air Force for a little background on the squadron The Coffin Crew were a part of!

SQUADRONS OF DEATH

The Epic Story of the Independent Air Force, the Most Amazing and Mysterious Organization of the World War in the Air

by A.H. Pritchard (Air Stories, December 1935)

A FEW months ago a story appeared in this magazine with the title of “Suicide Squadron.” Doubtless there were some readers who scoffed at this apparent exaggeration, refusing to believe that any form of aerial combat, even in time of war, could be so fraught with peril as to justify such a title. Yet truth is ever stranger than fiction, for here is the true story of the real “Suicide Squadrons” of the war. It is the story of a force that was composed entirely of such squadrons—the Independent Air Force.

Never before has the story of its epic deeds been presented in a magazine; its greatest deeds of heroism and daring are virtually unknown and, hitherto, unrecorded. Stories of the R.F.C., R.N.A.S., L’Aviation Militaire, and the Imperial German Air Force have appeared in their thousands, but seldom a line about the Independent Air Force. Nor do any of its pilots or observers appear on any list of British “aces,” yet dozens of German ’planes went down before the fury of their guns. Brief notices in the official despatches about a certain raid that “was successfully carried out” were all that the public ever learnt about the greatest fighting force in the Flanders skies.

Every man of them was a hero—they had to be, for a coward or a cautious man would not have lasted a day in their ranks. Their offensive policy always kept them flying over the enemy side of the lines. They fought their way to a target and then fought their way home, always against great odds. Many went down behind the German lines and spent the rest of the war in a prison camp, for a disabled ’plane meant certain capture. Yet, no matter how high the casualties, eager young men were always clamoring to join the Force. Men from every outpost of the Empire, from every walk of life, could be found in its roster, the most daring and reckless of their respective breeds.

The Birth of the I.A.F.

THE formation of the Independent Air Force was chiefly brought about by the intensive Gotha raids on England during the first six months of 1917. The public morale was slowly but surely being affected, and a demand went up for reprisals. “Give the Hun a taste of his own medicine,” was the cry. “Bomb his towns and his women and children!” So strong was this feeling that the War Office decided that something must be done, and they prepared to carry the war into Germany. However, all the squadrons at the front were far too busy to carry out the proposed raids, and it was decided to organise a separate force—a force that was to fight and raid under the direction of its own officers, not at the beck and call of the Army, as were the R.F.C. squadrons.

Accordingly, on October 11th, 1917, three squadrons were banded together as the Forty-First Wing, and were destined to form the nucleus of the Independent Air Force. These squadrons were No.55, No.100 and No.16 (Naval) Squadrons, and their ’drome was at Ochey. The total number of their machines was fifty-one. Beyond a few feeble raids, nothing much was heard of them until Major-General Sir Hugh Trenchard, Now Marshal of the Royal Air Force the Lord Trenchard Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, affectionately known to his men as “Boom,” arrived at Nancy on May 20th, 1918, to take command of what had then become officially known as the Independent Air Force. He found No.55 Squadron equipped with D.H.4 day-bombers (Rolls-Royce 375 h.p. “Eagle” VII’s) and No.100 with F.E.2b night-bombers (160 h.p. Beardmores), and he immediately applied for additions to his small force. He received No.33 Squadron, flying D.H.9’s (230 h.p. B.H.P’s) and No.216 Squadron, equipped with Handley-Page 0/400’s (two 250 h.p. Rolls-Royces), both stationed at Azelot.

Even then the Force did not really get into action, for delay was caused by the limited range of some of its machines. Only the Handley-Pages had a sufficient range to enable them to bomb the German frontier towns, and make the return journey. The normal duration of the F.E.’s and D.H.’s was only three and a half hours, so that extra petrol tanks had to be fitted to give them a duration of six hours, equivalent to a range of about 450 miles. Fuming at the delay in going into action, the men made the changes in record time, and in June, 1918, the I.A.F. set about its work of destruction, a work that was never to falter until Armistice was signed.

The Greatest Raid of the War

IN ITS first month of action the Independent Air Force carried out one of the greatest raids of the whole war. On the morning of June 28th a scout pilot spotted unusual enemy activity around Fere-en-Tardenois; dumps of ammunition were being made, and heavy transport lorries cluttered up the roads. Back he went to report the concentration, and the Independent Air Force was quickly informed. The ’dromes at Ochey and Azelot became seething ant-heaps of activity. All through the night great bombs were loaded into the gaping bellies of the Handley-Pages and the racks of the D.H.’s and F.E.’s were festooned with the steely beads of death. Working by the light of flares made from petrol-soaked cotton waste, the mechanics and armoury officers toiled on, whilst the pilots and observers tried to snatch a few hours’ sleep—for some the last that they were to take. Two hours before dawn machine-guns crackled harshly as they were tested at the butts.

Then, in the chilly air that comes in the pre-dawn, the four squadrons took-off, with a squadron of S.E.5’s following close behind, and with a roar rattled away towards their objective. The S.E.5’s had been lent by the R.F.C. to keep off enemy scouts until the bombers had laid their eggs.

Coming in over Fere-en-Tardenois at just under one thousand feet, they laid their bombs squarely on the first dump. A great sheet of flame leaped skywards, and debris rained around the bombers. Huge lorries hurtled up as the first great concussion set off the remaining dumps, and things that once had been men flew about the heads of the deafened Britishers. When the smoke had drifted away, all that remained of the woods that had concealed the dumps were a few fire-blasted stumps and smoking ruin.

The raiders, however, were not to escape unscathed. Fokkers, Pfalz, Albatri and “Tripes” gathered round them like flies round a jam-pot. Machine-guns rattled madly, tracer bullets weaved fantastic patterns across the sky, and an F.E.2b was the first to go. Caught in the converging fire of three Fokkers, its wings dropped off like pieces of paper, and the fuselage fell like a stone, burning fiercely. A second later two Pfalz collided and fell burning, leaving a trail of smoke and blazing fragments. Thirteen British bombers went down in the battle that followed, and five S.E.5’s, but the rest fought their way out, leaving behind them the shattered wrecks of twenty-six German machines.

Apart from the damage done, the raid had served another good purpose, for the War Office, at first inclined to be parsimonious, now gave Trenchard all the men and material he required. Workshops sprang up on the ’dromes of the I.A.F., and even their own intelligence service was formed. Spies would cross the lines into Germany and send back information as to new dumps, troop concentrations, schedules of munition trains and new factories, and the lads of the I.A.F. would go over and do the rest.

“Jock” Mackay Leads the Attack

ON the morning of July 31st, word came from one of their agents of the massing of supplies in the big station at Saarbrucken. Nine D.H.9’s of No.99 Squadron were quickly loaded with bombs and set off post-haste for Germany. Ten miles from their objective they were attacked by forty-six enemy scouts. Four D.H.’s went down, but the remaining five fought their way through and dropped their bombs dead on the station yards. A running fight all the way home awaited the survivors, and three more went down before they could reach the safety of No.55 Squadron’s field at Ochey. No sooner had the two battered machines landed than nine more D.H.4’s, this time of No.55 Squadron, took off for Saarbrucken. Under the leadership of Captain D.R. (“Jock”) Mackay, one of the best bomber pilots of the war, they found the stations and factories unprepared for this second raid, and exacted a terrible toll as revenge for the fourteen gallant men who had died in the first raid. After taking part in over a hundred raids, the gallant Mackay met his death through a direct hit from “Archie” on the day before the Armistice was signed.

The German towns that were coming in for the heaviest bombing raised a furious protest at the tactics of the I.A.F. pilots, and the Imperial High Command allotted twelve new squadrons to protect the towns along the Rhine. Thus did the I.A.F. make its might felt, after only one short month of action. The German bombers, too, tried to get even with them. The F.E.2b’s of No.100 Squadron had specialized in raiding Saarburg, Metz and Conflans, and had played havoc with the factories there. The first German raid on their field wounded a mechanic and wrecked an empty hangar. Five nights later they tried again, and had the satisfaction of seeing a number of fires light up, machines burst into flames, and a hangar collapse. Early the next morning two high-flying Rumplers came over and photographed the damage. The prints, which can still be seen at the German War Museum, showed burnt-out hangars and wrecked machines, whilst the sleeping quarters were a shambles.

And the men of No.100 Squadron laughed loud and long.

For the fires had been caused by petrol-soaked rags ignited by a timing device, the hangar was an old one, and the wrecked machines were old, crashed ’planes and tree trunks. After that first raid, Major Tempest, the C.O., had had the Squadron moved to the opposite side of Ochey Woods, and all hands turned out to sit in the trees and watch the display of fireworks provided nightly by the German Air Force. The Germans never could make out how it was that the Squadron continued to carry out its two raids a night.

Fighting Against Odds

MEANWHILE, the enemy air resistance was becoming stronger. Reinforced by the twelve new squadrons, they attacked every group of British machines that ventured near the Rhine towns. Undeterred, the bombers carried on, but their casualties became terribly heavy. Take the case of one raid by six D.H.4’s of No.55 Squadron.

On the morning of August 27th, they set out to bomb the docks at Offenburg, and when over the town were attacked by a formation of eight Pfalz scouts. Such odds were familiar to them, and, unperturbed, they carried on with the raid and turned for home. Then came disaster. Another formation of thirty Pfalz, Albatri and Fokkers came down on them, and after a running fight lasting over an hour, only one D.H. managed to limp home. True, three German ‘planes had gone down in flames, but the score was on the wrong side of the ledger. Still, no squadron could fight against the odds they were meeting and get away scot-free every time.

On the 10th of the month the same squadron had been attacked by thirty enemy scouts whilst returning from a raid on Frankfort. Flying a tight formation, they held the attackers off, and even when the enemy was reinforced by another forty machines they never broke formation. Against seventy enemy scouts not a British machine went down, and only one observer was killed. Four German ’planes were sent flaming to earth.

Two days later twelve machines took-off for another raid on Frankfort, as usual, without any escort of single-seaters. They carried out the raid unhindered, but on the return journey the inevitable enemy scouts appeared. Thirty-five Huns opposed them, and after a running fight that lasted an hour and twenty minutes, ten German machines had been destroyed, while the twelve bombers escaped with nothing worse than bullet-riddled machines.

The Handley-Pages of No.216 Squadron had also been giving a good account of themselves. On August 21st, in a raid that lasted over six hours, two H.P.’s had dropped over a ton of bombs on Cologne station, and had destroyed three enemy ’planes on the way home.

Besides the enemy aircraft, the British fliers had another great enemy to face, and one that the German pilots were never troubled with. Every English ’plane that crossed the German lines had the wind to contend with on its return journey. Always blowing out of Germany, many pilots owed their forced landings and subsequent capture to them. Even the I.A.F. had losses due to this wind.

One case, in example, was the fate of seven Handley-Pages of No. 216 Squadron. On the night of September 16th they set off to raid Mannheim. They bombed the chemical works and aircraft factories, fought off a dozen enemy scouts, and then started for home. When still many miles from the British lines one of their number went down, due to a shortage of petrol, and one after another the rest of the raiders followed suit. An extra strong wind had upset all their calculations, and seven 0/400’s were presented to the enemy by a trick of the wind.

The objectives chosen by the I.A.F. bombers were in some cases over one hundred and seventy miles away, and some idea of what the men had to put up with can be obtained when one remembers that even if the outward journey was fairly safe, the raiders had still to run the gauntlet of every available enemy squadron over that one hundred and seventy miles of the journey back. In the wind and blinding rainstorms of September and October they carried on, and their proud boast was that no raid was ever cancelled on account of inclement weather.

The Coming of the Giants

BY NOW the Independent Air Force was no longer an experiment. It was a tried fighting force, and the War Office knew it. All the men and machines that Trenchard required were now given to him freely, and many American officers, who had been chafing at the inaction while waiting for their own country to obtain ’planes, were transferred to the I.A.F.

New machines were needed to carry the raids still further into Germany, and great pressure was brought to bear on the aircraft works at home. The De Havilland people were trying out a new type of ’plane with the factory number of D.H.17. The machine was totally enclosed, and well streamlined, but except for the first experimental model, it never went into production. The same firm also had the twin-engined D.H.10 and D.H.10a., but neither machine fully satisfied Trenchard. The Handley-Page and Vickers factories, however, were building real dreadnoughts of the sky. The Vickers machine was the famous Vickers Vimy, and was powered with two 350-h.p. Rolls-Royce engines, and had a wing span of sixty-eight feet. But it was the machine being made by the Handley-Page works that really appealed to Trenchard. This was the V/1500 and in general appearance it was similar to the O/400. It was powered, however, with four 360-h.p. Rolls-Royce “ Eagle ” engines that could send the monster along at 103 miles an hour, with its full bomb load of 2,700 pounds. It had a non-stop range of one thousand three hundred and fifty miles, and could soar up to ten thousand feet in twenty minutes. Small wonder that “Boom” expected great things from it.

Meanwhile, the men at the front were carrying on in air that bristled with enemy fighters, whose instructions were to stop them at all costs.

On September 25th, No.110 Squadron went out to bomb Frankfort. They had been with the I.A.F. only a short time, and it was to be their first long-distance raid. Over Frankfort they were met by a terrific “Archie” fire and shells by the dozen burst all round them. Luckily, none was hit, and after dropping a ton and a half of bombs on the railway and goods yard, they turned for home. Summoned by the black bursts of the anti-aircraft shells, the enemy scouts came down, thirsting for blood. Four bombers went down, two Observers were killed, two pilots and one observer wounded. Only two German machines had been observed to fall, one in flames and one “out of control.”

The German scout pilots were now fighting with redoubled fury. The I.A.F. bombers were doing great execution among the troops quartered at Metz and Luxembourg, and had effectively shattered their morale. Twice, towards the middle of October, the troops in these towns had threatened to mutiny. A whisper went round that an armistice was coming and that the enemy pilots had determined to give a good account of themselves before the end came.

Blind Bombing

Sometimes, though, the I.A.F. outguessed the Germans and eluded the enemy scouts.

On the night of October 21st-22nd, a great raid was planned on the barracks and railway yards at Kaiserslautern, and Nos.97 and 100 Squadrons were given the job. It was a night of wind, rain and fog, with visibility almost nil, but the squadrons refused to cancel the attack. Taking-off down a lane of flares, they climbed above the fog blanket and set a course for Kaiserslautern. The journey became a nightmare as the weather got steadily worse. Blinded by the rain, and unable to catch a glimpse of the ground below, the fliers fought against the elements until their instruments showed them to be in the vicinity of their objective. Going down through the fog they could just faintly discern the lights of the town. Down screamed the bombs, and several large fires were observed to spring up, but, due to the mist obscuring the target, no definite report of the damage could be made.

Groping their way homeward, nearly every machine made a forced landing. One machine cracked up against a tree when attempting to land in a “pocket handkerchief” field, but, apart from the observer breaking his little finger, both occupants escaped scot-free. This was the only casualty, for every machine got back safely. Not an enemy scout had been seen during the whole time that they had been out, for the enemy protection squadrons had not dared to take-off in the fog. Some idea of the accuracy of the navigation may be obtained from the German official report of this raid, which stated that two hits had been made on the barracks, and the railway track had been badly damaged by a direct hit from a 650-pound bomb.

Berlin to be Bombed

BACK in England the work of forming still more I.A.F. squadrons was going forward apace, and on November 2nd these squadrons embarked for France—complete with the new and deadly giant bombers. Then came the news that set every flying man agog with excitement, and caused the blood to course the quicker through their veins—Berlin was to be bombed on November 18th by three full squadrons of Handley-Page V/i500’s and the total force was to consist of nearly one hundred machines!

For a week skilled mechanics toiled with loving care over the engines of the giants, and by the 10th the great machines were ready to go. That night came the greatest blow the Independent Air Force had ever suffered; orders were given for all preparations to be cancelled. On November 11th the wings of the Black Eagle folded in the dust, and the long story of bloodshed was over. Who knows—but perhaps advance news of the proposed raid had done much to persuade the Germans to beg for an armistice. To a country already bled white by four years of bitter strife, a raid on its capital might well have been feared as a means of setting ablaze the smouldering fires of revolt.

The morning of the 11th was the first to which the Independent Air Force did not awaken to the thunder of guns. No more for them the rattle of machine-guns, the tight feeling inside as the enemy hove into view, the hoarse “woof-woof” of “Archie,” the banshee wail of falling bombs, or the shrill scream of wires. All that was over, the world was at peace, and who can blame them if they felt thwarted of their last, and, what would have been, their most glorious fight. The day of the Independent Air Force was over.

In the few months of its existence the force had carried out over seven hundred raids, had dropped 160 tons of bombs by day and 390 tons by night, and had done damage to the extent of millions of pounds. Two hundred of these raids had been on enemy aerodromes, and much of the Imperial Air Force’s effectiveness had been quenched. In their battles with the enemy scouts they had lost one hundred and eleven machines, but one hundred and fifty-seven German machines had been destroyed by their guns, and over two hundred driven down out of control. That alone put them on the right side of the final account. Their men had fought the best that the enemy could send against them and beaten them in fair fight over their own ground. Their continual raids on the great gas-plants at Mannheim had been instrumental in saving the lives of countless infantrymen, and their systematic bombing of the enemy supply areas, dumps, and munition works did much to bring about the final downfall of German arms.

Never more than eleven squadrons strong, they had done the job expected of them, and they leave behind a glorious tradition. Born in the War, and fated to die in the War, we should salute—and remember—them.

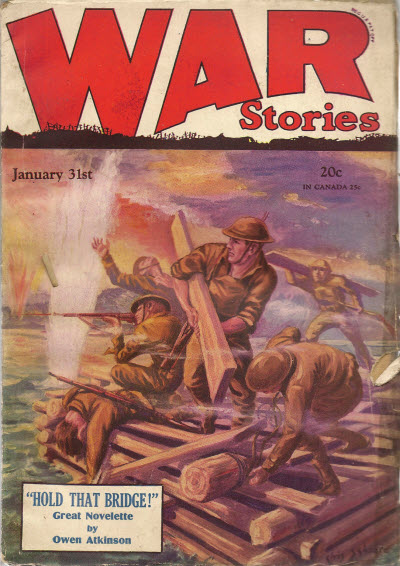

by the prolific O.B. Myer’s! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Following up his first story last week, we have his second published story. “Pip” Preston brings down the great von Stangel. But von Stangel turns out to be an undercover agent…. From the pages of the January 31st, 1929 issue of War Stories it’s O.B. Myer’s “The Buzzard’s Guest!”

by the prolific O.B. Myer’s! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Following up his first story last week, we have his second published story. “Pip” Preston brings down the great von Stangel. But von Stangel turns out to be an undercover agent…. From the pages of the January 31st, 1929 issue of War Stories it’s O.B. Myer’s “The Buzzard’s Guest!” Well, I’ve got a bit of real news that may be of interest. Your boy is “flying very high these days’’ I bumped into another old Mount Vernonite, old Oscar Myers, who is first lieutenant in the aviation. We sat around and talked for awhile and he said if the weather was fine the following day he would give me the flight or fright of my life. You can bet I was Johnny Thomson on hand—and up we went. Holy smoke! I thought for sure I was straight on my way to meet St. Peter. The earth soon faded beneath us and I found myself passing as Myers called it, through cloud banks. Gee! but it sure was a funny feeling. We dropped down a few hundred feet, about 600 or 700 and gradually mother earth hove into view. Then he thought he would pull a few stunts as he called it, and so he looped the loop, glided, banked and a few others which I forgot in the excitement and then we made a beautiful volplane to the sod. Well, I Just can’t begin to explain or express the feeling one has while in the air, or while doing some of those things, but one thing I can say is this. Before going up we were strapped into the seats with a big strap across our chest and when doing the loop, the machine is turned completely upside down and there we were out of our seats and lying flat on this belt face to earth. Boy, oh boy! that’s the only time I said good-bye to friends so dear, to home and mother in fact everything, but it was only for a moment for he again righted her and it was over. I’ve given you but a vague description, Mother and Dad, but I guess you can get some idea as to what we did. Just as soon as I have a chance again and it’s a fine day, I’m going to bring Mac over and the three of us are going up.

by the prolific O.B. Myer’s! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the

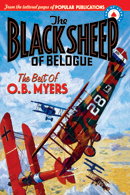

by the prolific O.B. Myer’s! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the  O.B. Myer’s didn’t really have any series characters. The few recurring characters he did have in the pages of Dare-Devil Aces, we’ve collected into a book we like to call “The Black Sheep of Belogue: The Best of O.B. Myers” which collects the two Dynamite Pike and his band of outlaw Aces stories and the handful of Clipper Stark vs the Mongol Ace tales. If you enjoyed this story, you’ll love these stories!

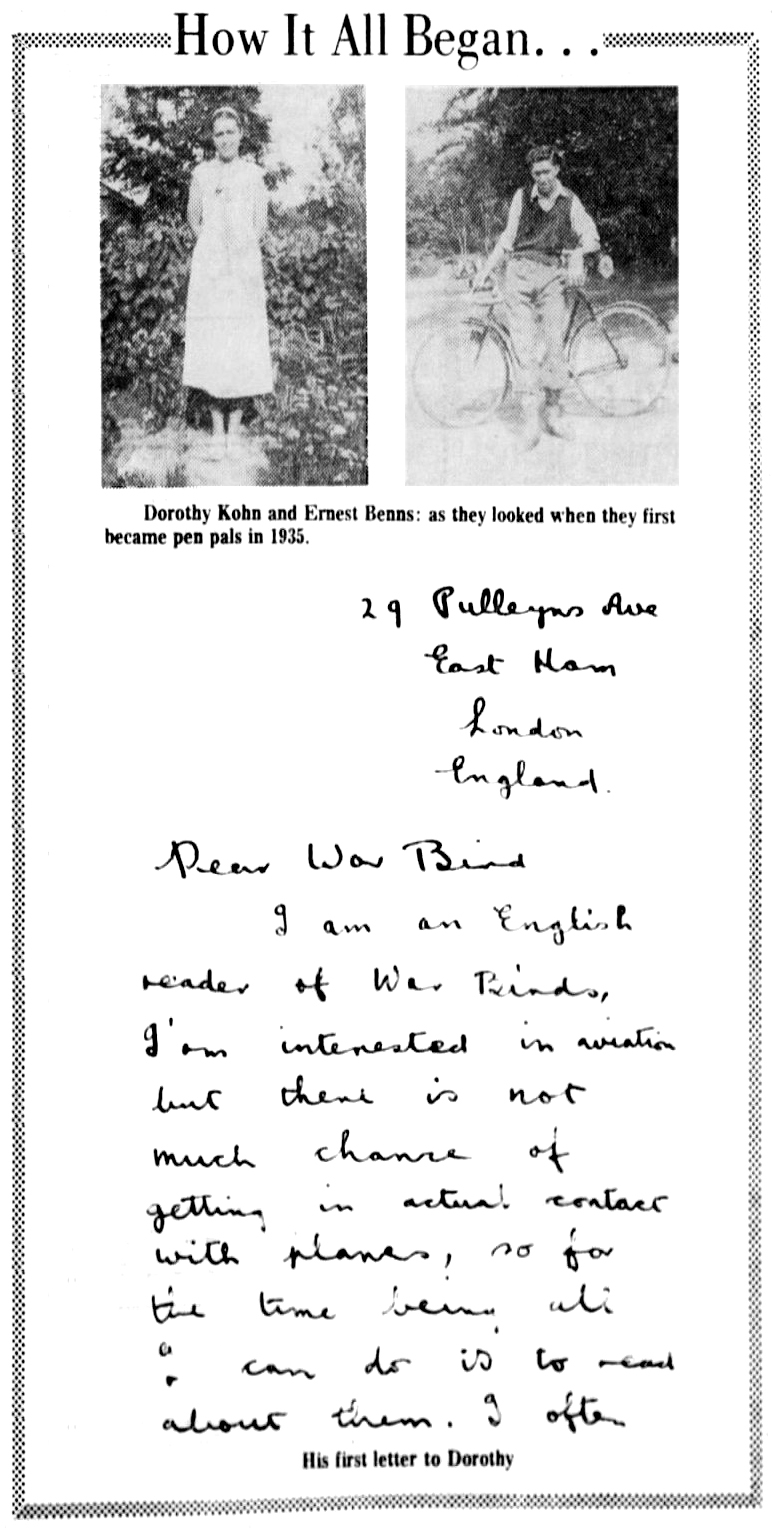

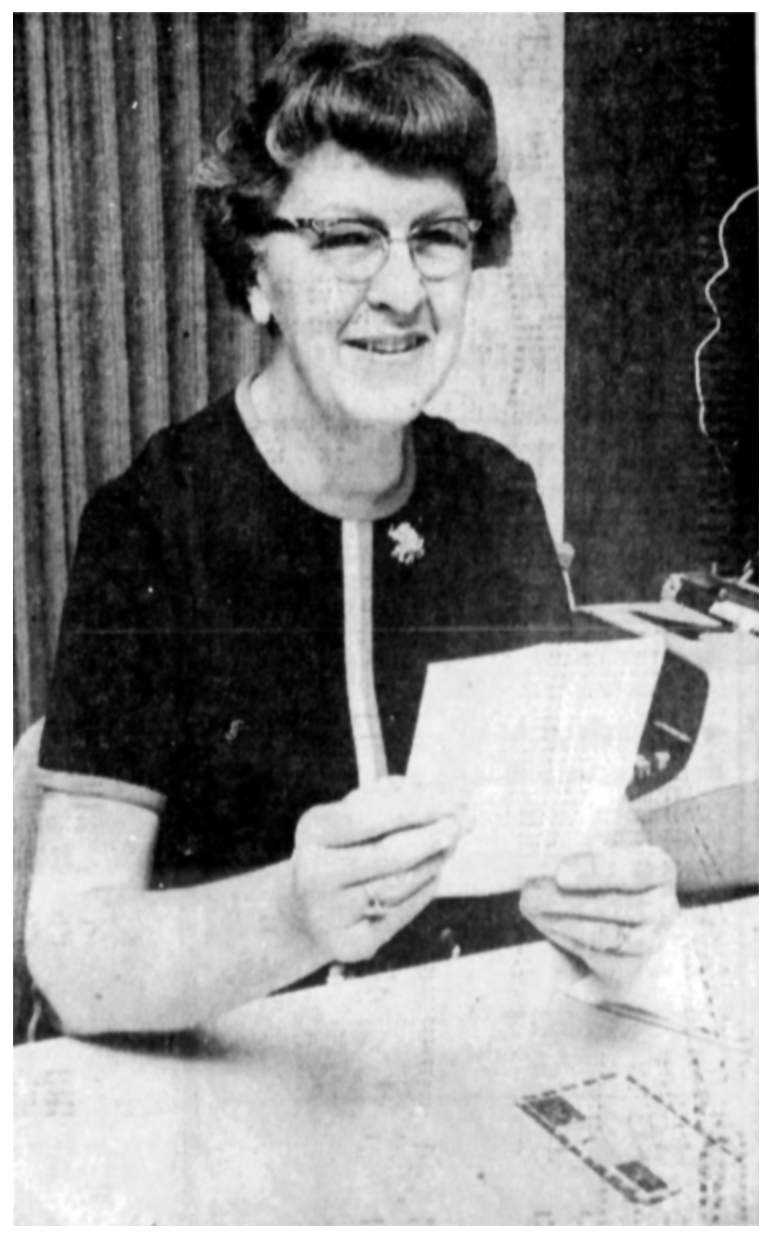

O.B. Myer’s didn’t really have any series characters. The few recurring characters he did have in the pages of Dare-Devil Aces, we’ve collected into a book we like to call “The Black Sheep of Belogue: The Best of O.B. Myers” which collects the two Dynamite Pike and his band of outlaw Aces stories and the handful of Clipper Stark vs the Mongol Ace tales. If you enjoyed this story, you’ll love these stories! Dorothy would go on to be quite active in the club pages. In December 34 she was awarded both a citation for her letter in perfect military form containing six suggestions and a proposed new membership card; and a promotion to 1st Lieutenant (effective October 1st 1934). She garnered additional citation the following year. In January for a very interesting report on the first Mississippi commercial seaplane; February for submitting suggestions and reports in military fashion and, particularly, for an excellent report on her local airport; and in the final month, June, for exceptional service. Dorothy was listed as being a member of Iowa’s 39 Squadron in all her citations rather than the Lady Bird’s 80 Squadron.

Dorothy would go on to be quite active in the club pages. In December 34 she was awarded both a citation for her letter in perfect military form containing six suggestions and a proposed new membership card; and a promotion to 1st Lieutenant (effective October 1st 1934). She garnered additional citation the following year. In January for a very interesting report on the first Mississippi commercial seaplane; February for submitting suggestions and reports in military fashion and, particularly, for an excellent report on her local airport; and in the final month, June, for exceptional service. Dorothy was listed as being a member of Iowa’s 39 Squadron in all her citations rather than the Lady Bird’s 80 Squadron.

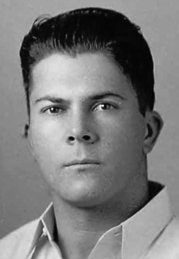

ROBERT LEO MEADE, Jr. (Jul 20, 1913 – Aug 6, 2000) Flight Commander and driving force behind the club, he had been a Junior Assistant Scout Master back in his Boy Scout Days and was the oldest member of the Lucky Seven at 20 when they formed. Born in Galveston, he served in the Navy aboard the USS PLUNKET during World War II and worked for the Civil Air Patrol afterwards being described as a Second Lieutenant in 1953. He married in 1954. At some point he moved to Robertsdale, Alabama near Mobile. He passed away there on August 6th, 2000.

ROBERT LEO MEADE, Jr. (Jul 20, 1913 – Aug 6, 2000) Flight Commander and driving force behind the club, he had been a Junior Assistant Scout Master back in his Boy Scout Days and was the oldest member of the Lucky Seven at 20 when they formed. Born in Galveston, he served in the Navy aboard the USS PLUNKET during World War II and worked for the Civil Air Patrol afterwards being described as a Second Lieutenant in 1953. He married in 1954. At some point he moved to Robertsdale, Alabama near Mobile. He passed away there on August 6th, 2000. (Sep 25, 1918 – Jul 25, 1963) William Ague was born in Sewickley, Pa, just outside Pittsburgh in on September 25, 1918, moving to Galveston in 1920. He was employed by the City of Galveston Water Department as a pipe fitter until the time of his illness. He was a veteran WWII where he was a Private First Class with the 385th Bombardment Squadron Army Air Forces. He is survived by his mother and younger sister. (

(Sep 25, 1918 – Jul 25, 1963) William Ague was born in Sewickley, Pa, just outside Pittsburgh in on September 25, 1918, moving to Galveston in 1920. He was employed by the City of Galveston Water Department as a pipe fitter until the time of his illness. He was a veteran WWII where he was a Private First Class with the 385th Bombardment Squadron Army Air Forces. He is survived by his mother and younger sister. ( WILLIAM ASHTON MEADE (Feb 2, 1917 – Jun 21, 1990) From his

WILLIAM ASHTON MEADE (Feb 2, 1917 – Jun 21, 1990) From his  (May 1, 1919 – Sep 7, 1996) From his

(May 1, 1919 – Sep 7, 1996) From his  (Aug 2, 1914 – Nov 10, 1994) From his

(Aug 2, 1914 – Nov 10, 1994) From his  (Nov 2, 1913 – Jul 21, 1954) Francis Barnett Dwyer was born November 2, 1913, in Galveston and lived there in his boyhood. He had moved to Houston with his step-father and mother in 1937, finding work with general contractor as a carpenter’s helper. He married his first wife just after Christmas in 1942, with a bouncing bay girl girl June born the following year. He served with the U.S. Armed forces in Italy in 1944 . Upon his return, his family grew with the birth of two more sons, Thomas and Joseph. And Francis found work as a pipe fitter for the Houston National Gas Company. He was still employed with them when he passed away from testicular cancer at 40 in 1954 leaving behind a second wife, daughter and two sons. (

(Nov 2, 1913 – Jul 21, 1954) Francis Barnett Dwyer was born November 2, 1913, in Galveston and lived there in his boyhood. He had moved to Houston with his step-father and mother in 1937, finding work with general contractor as a carpenter’s helper. He married his first wife just after Christmas in 1942, with a bouncing bay girl girl June born the following year. He served with the U.S. Armed forces in Italy in 1944 . Upon his return, his family grew with the birth of two more sons, Thomas and Joseph. And Francis found work as a pipe fitter for the Houston National Gas Company. He was still employed with them when he passed away from testicular cancer at 40 in 1954 leaving behind a second wife, daughter and two sons. ( JULES JOSEPH LAUVE, Jr. (Dec 6, 1916 – Feb 7, 1998) From his

JULES JOSEPH LAUVE, Jr. (Dec 6, 1916 – Feb 7, 1998) From his  (Dec 5, 1918 – Dec 18, 1993) Cornelius Lauve was born Dec. 5, 1918, in Galveston. Before he enlisted Lauve was employed as teller at the W.M. Moody bank in Galveston. He served in the 15th U.S. Army Air Force, 449th Bomb Group in the European Theater operation in Italy and Africa for nine months during World War II. When he returned stateside, he was stationed at Harlingen Army Air Field, as an instructor at the gunnery school. He was the shop foreman at his bother’s outdoor advertising sing shop from 1946 to 1983 when he retired. He was a Master Electrician, member of the St. Patrick’s Men’s Club, member of Msgr. Kirwin Council #787 and Duck’s Unlimited. He was married and had two children. (

(Dec 5, 1918 – Dec 18, 1993) Cornelius Lauve was born Dec. 5, 1918, in Galveston. Before he enlisted Lauve was employed as teller at the W.M. Moody bank in Galveston. He served in the 15th U.S. Army Air Force, 449th Bomb Group in the European Theater operation in Italy and Africa for nine months during World War II. When he returned stateside, he was stationed at Harlingen Army Air Field, as an instructor at the gunnery school. He was the shop foreman at his bother’s outdoor advertising sing shop from 1946 to 1983 when he retired. He was a Master Electrician, member of the St. Patrick’s Men’s Club, member of Msgr. Kirwin Council #787 and Duck’s Unlimited. He was married and had two children. ( JOHN RUSSEL MULLINS (Apr 26, 1916 – Dec 26, 1994) From his

JOHN RUSSEL MULLINS (Apr 26, 1916 – Dec 26, 1994) From his

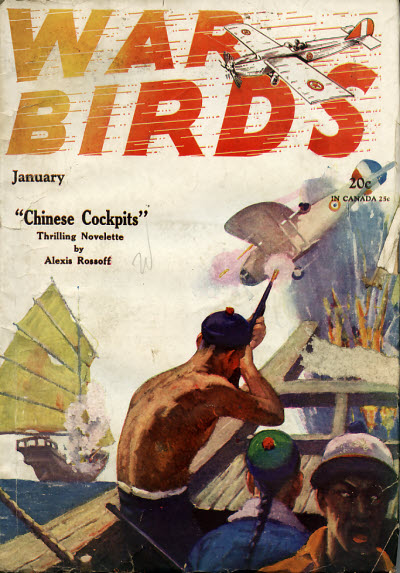

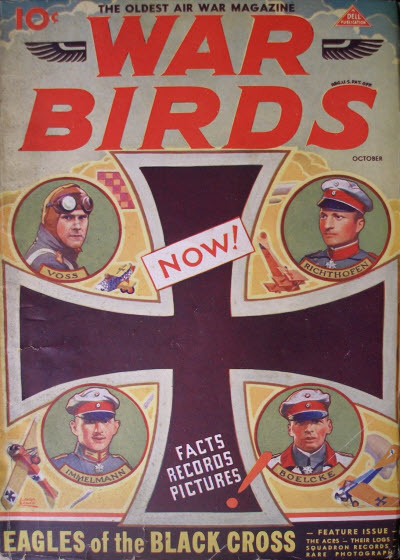

WAR BIRDS hit the stands with Belarski’s Eagles of the Black Cross cover and a wealth of stories within lead off by William E. Barrett’s factual article that goes with the cover. There were also stories by

WAR BIRDS hit the stands with Belarski’s Eagles of the Black Cross cover and a wealth of stories within lead off by William E. Barrett’s factual article that goes with the cover. There were also stories by

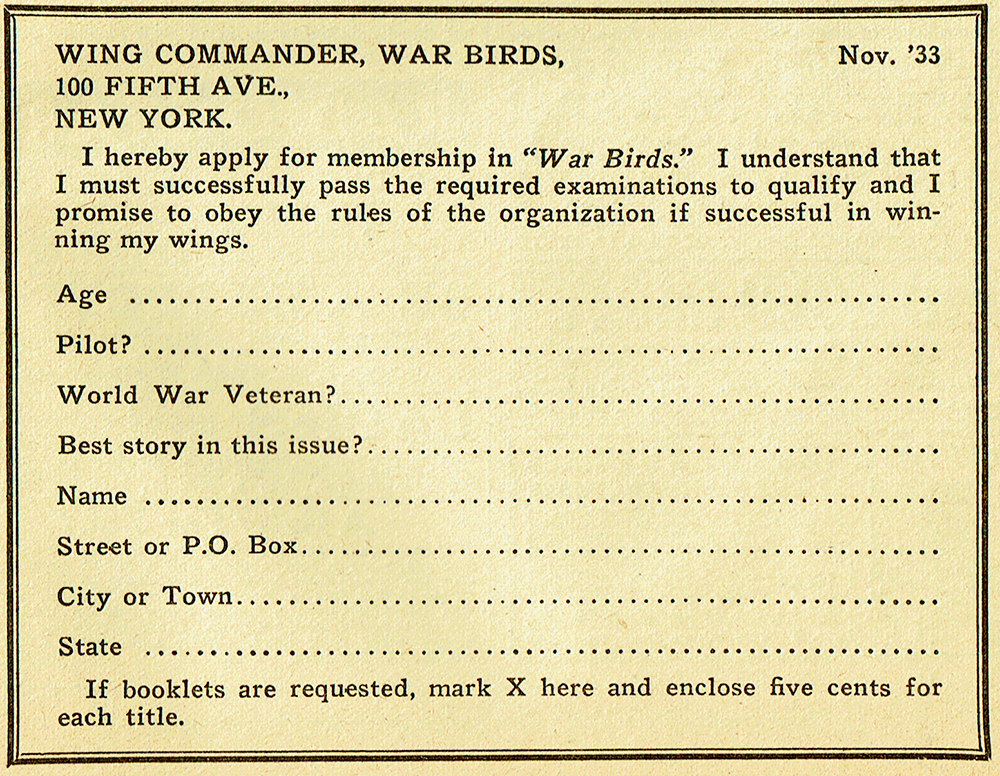

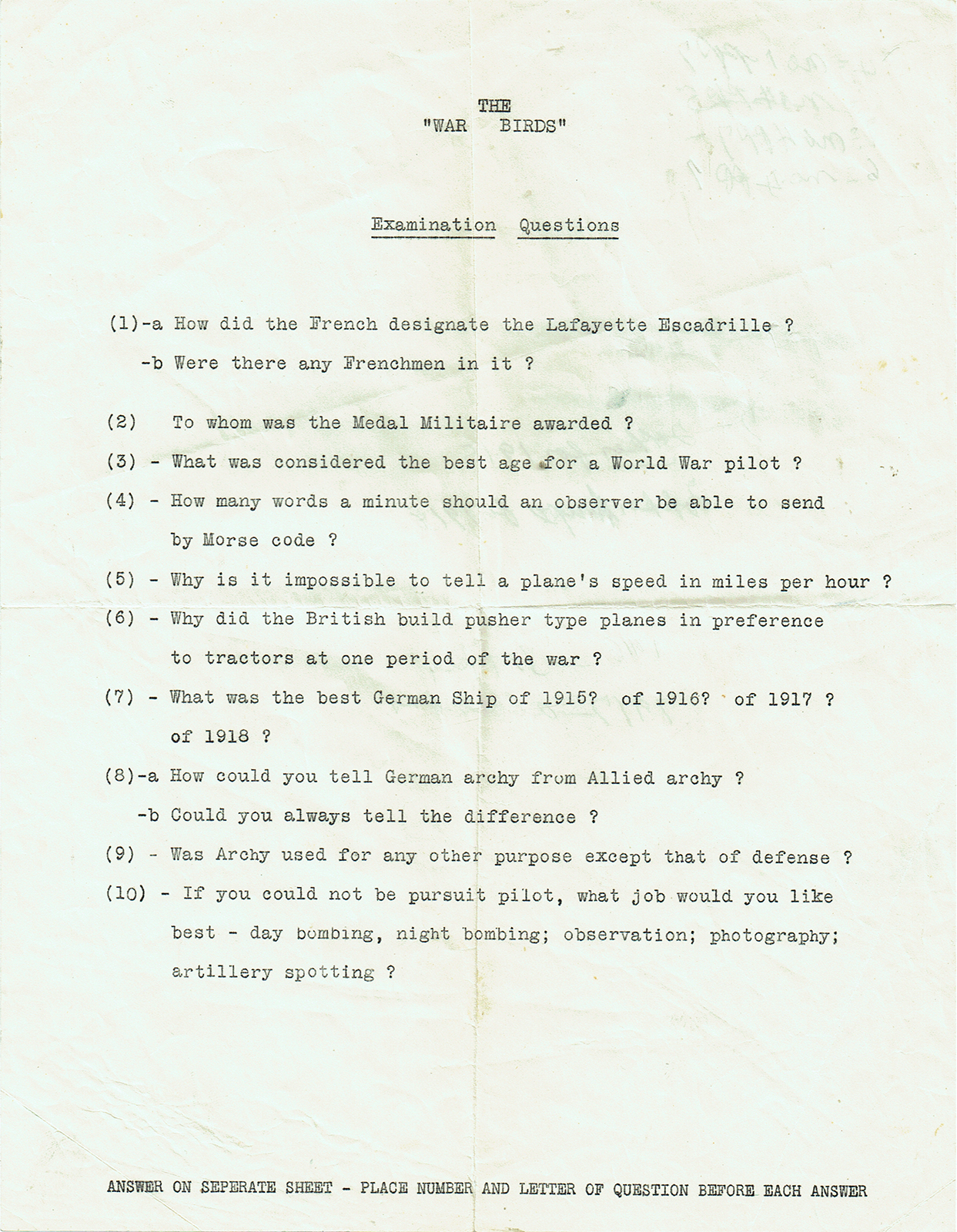

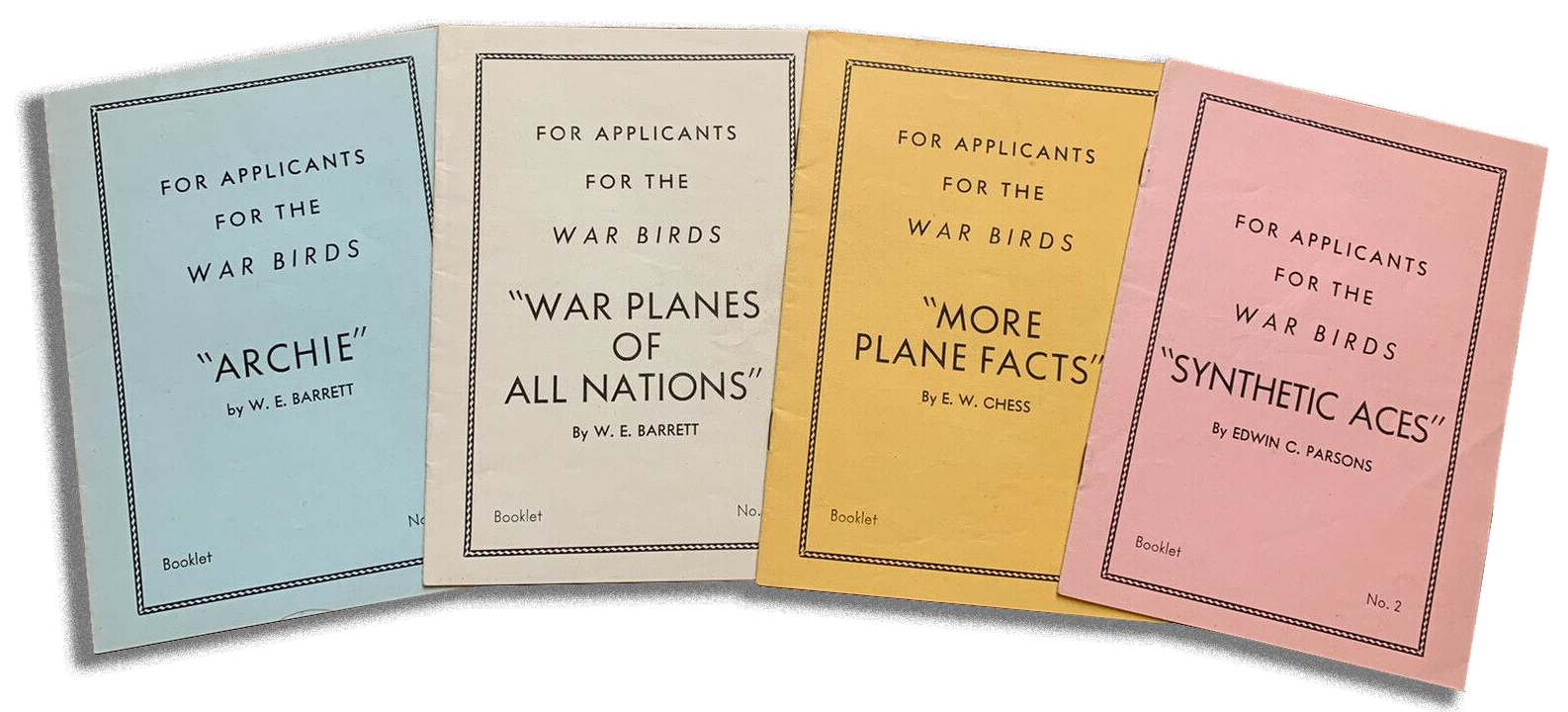

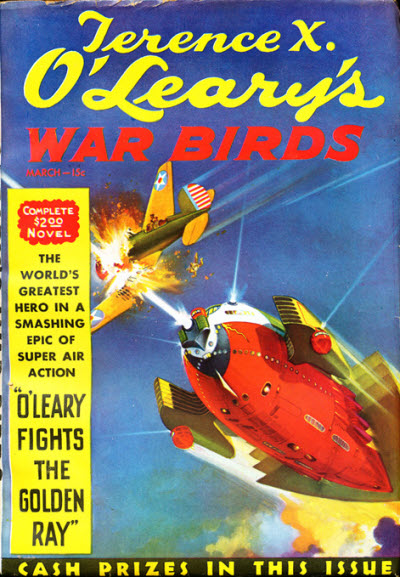

WITH the March Issue, WAR BIRDS changes it’s name to TERENCE X. O’LEARY’S WAR BIRDS and it’s focus. The lead story will now feature the exploits of Arthur Guy Empey’s Terence X. O’Leary, but the stories are more science-fictiony that O’Leary’s previous exploits in the magazine which were set in WWI. THE COCKPIT column continues with all it’s previous sections. And the coupon to join is still included. The Booklets can still be obtained for 5¢ and the wings are a bargain at 15¢.

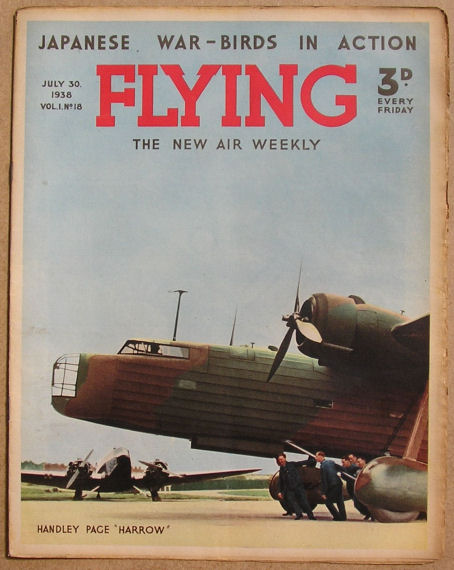

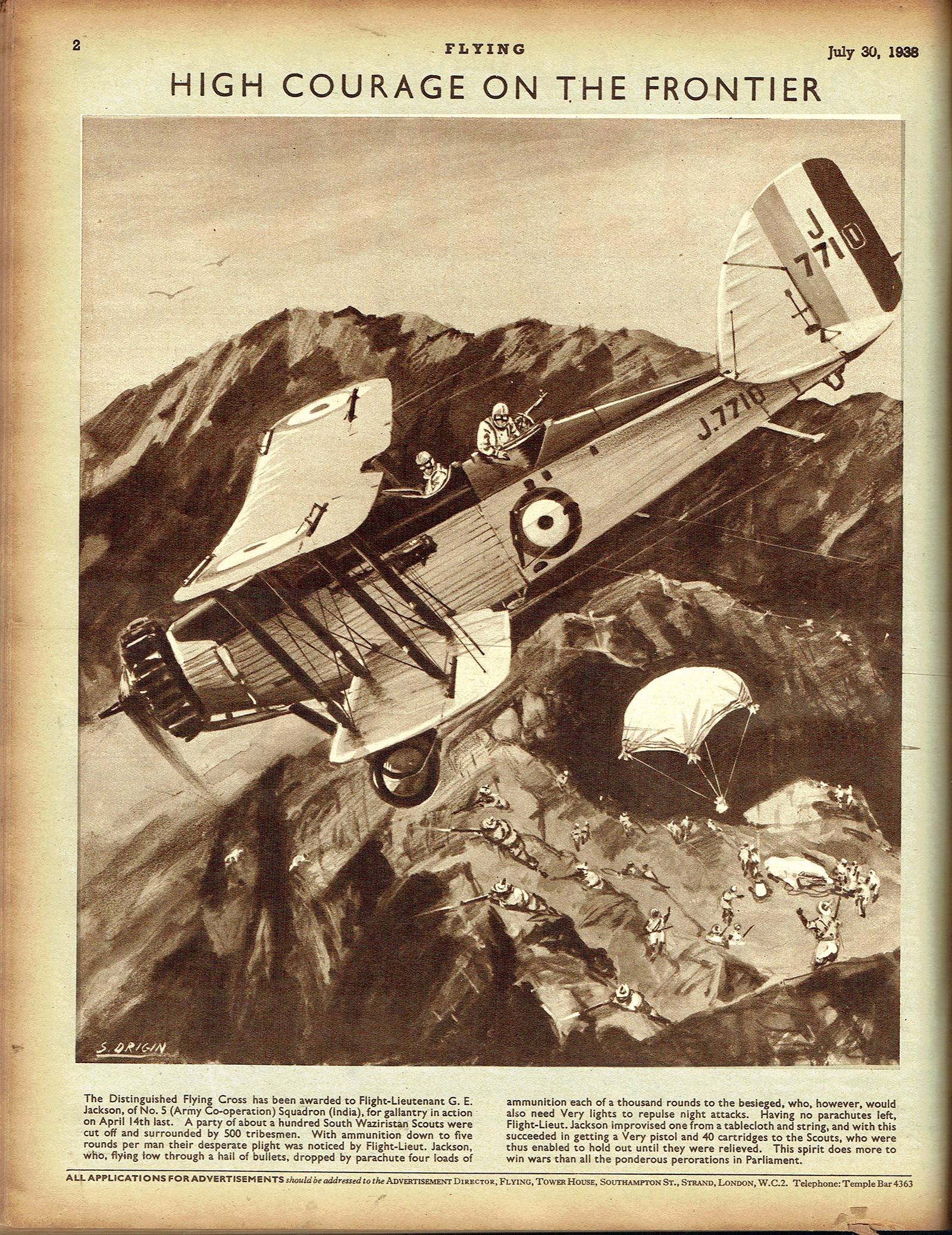

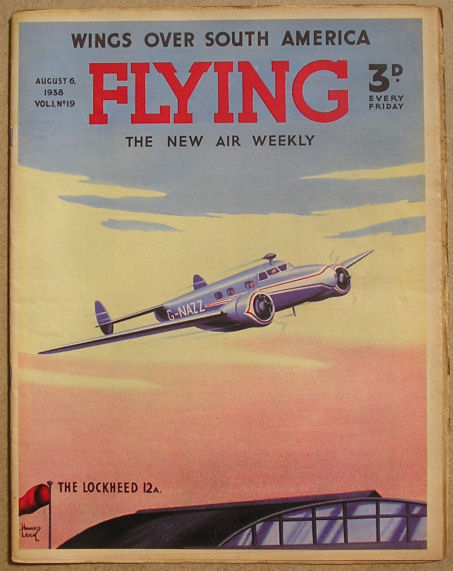

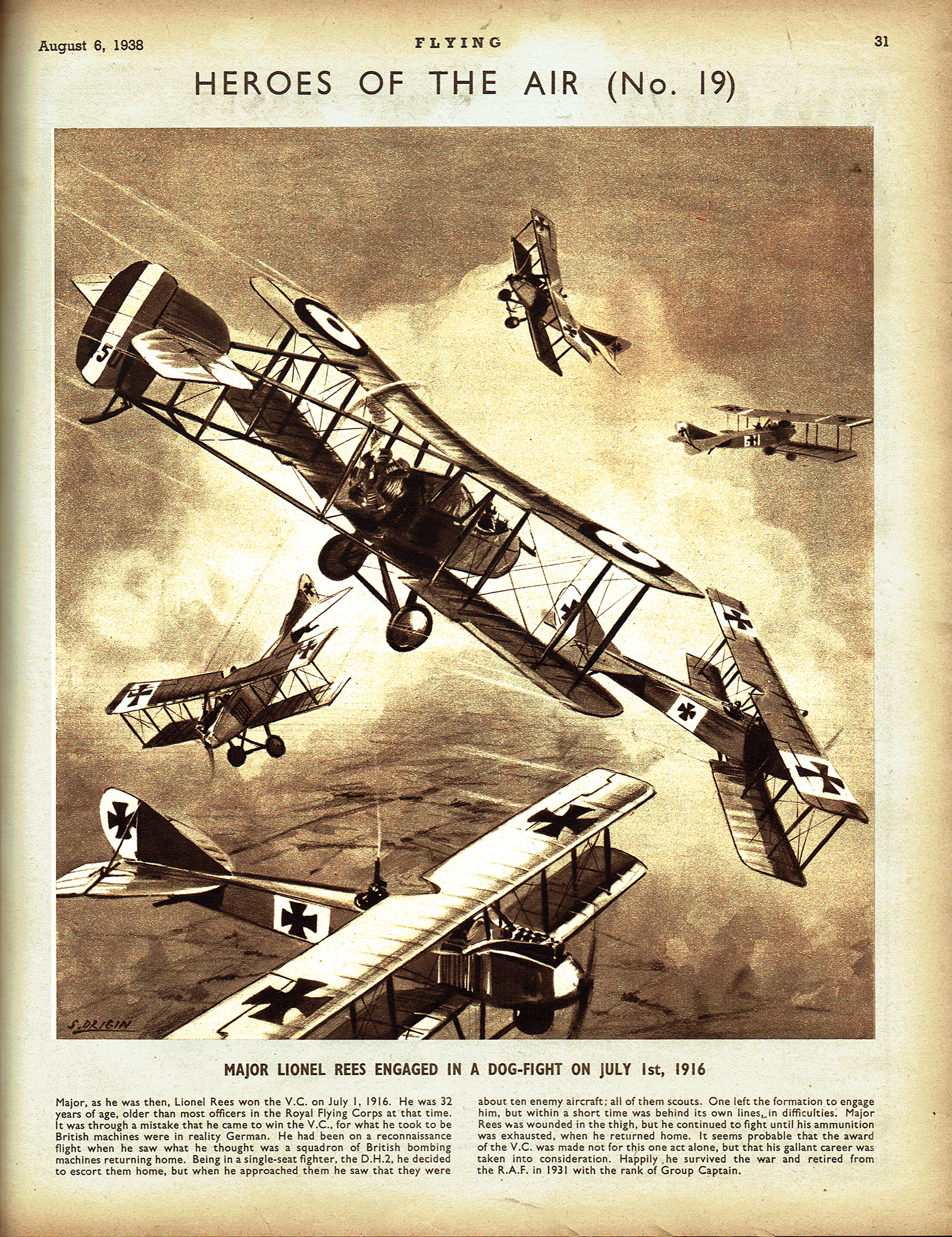

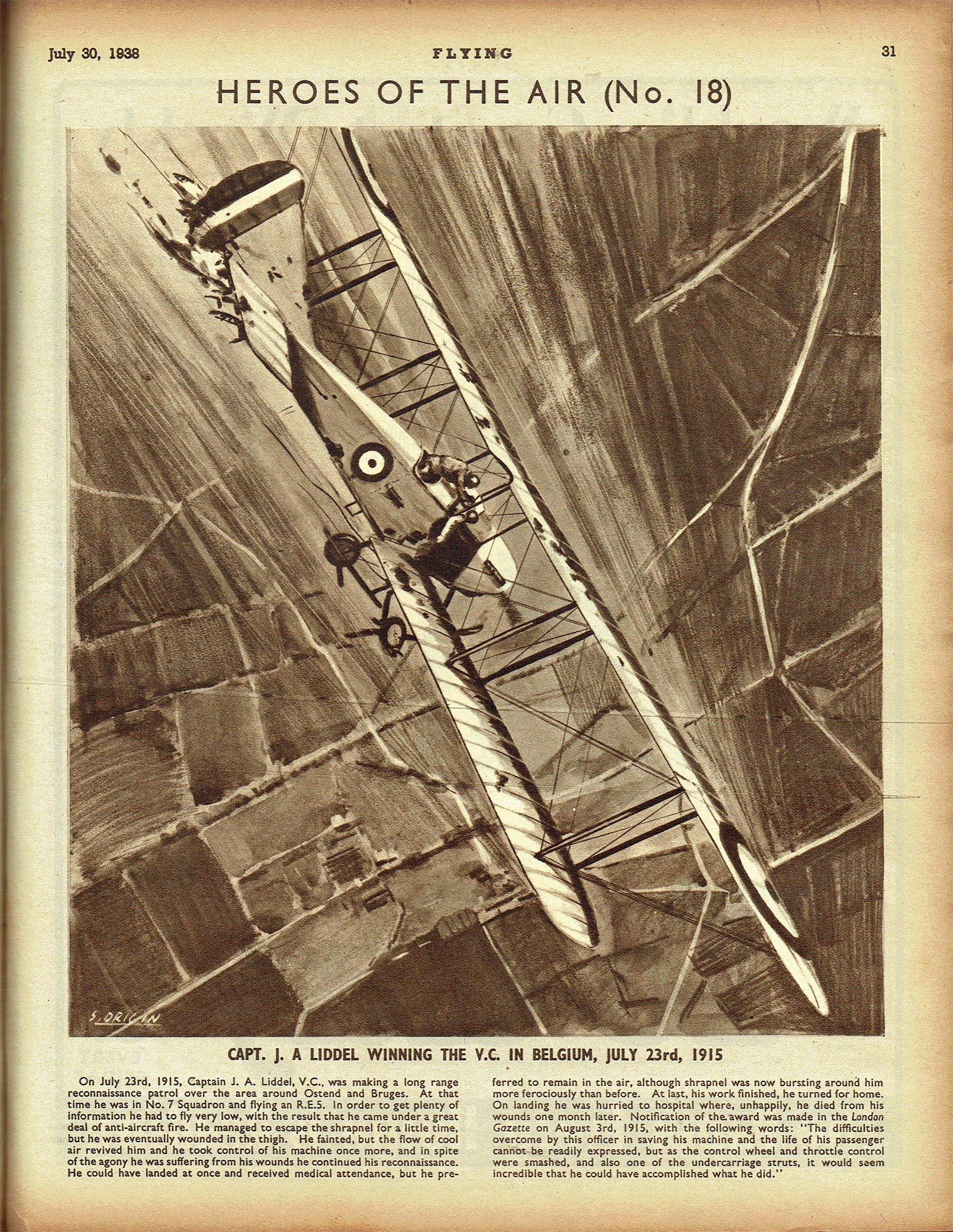

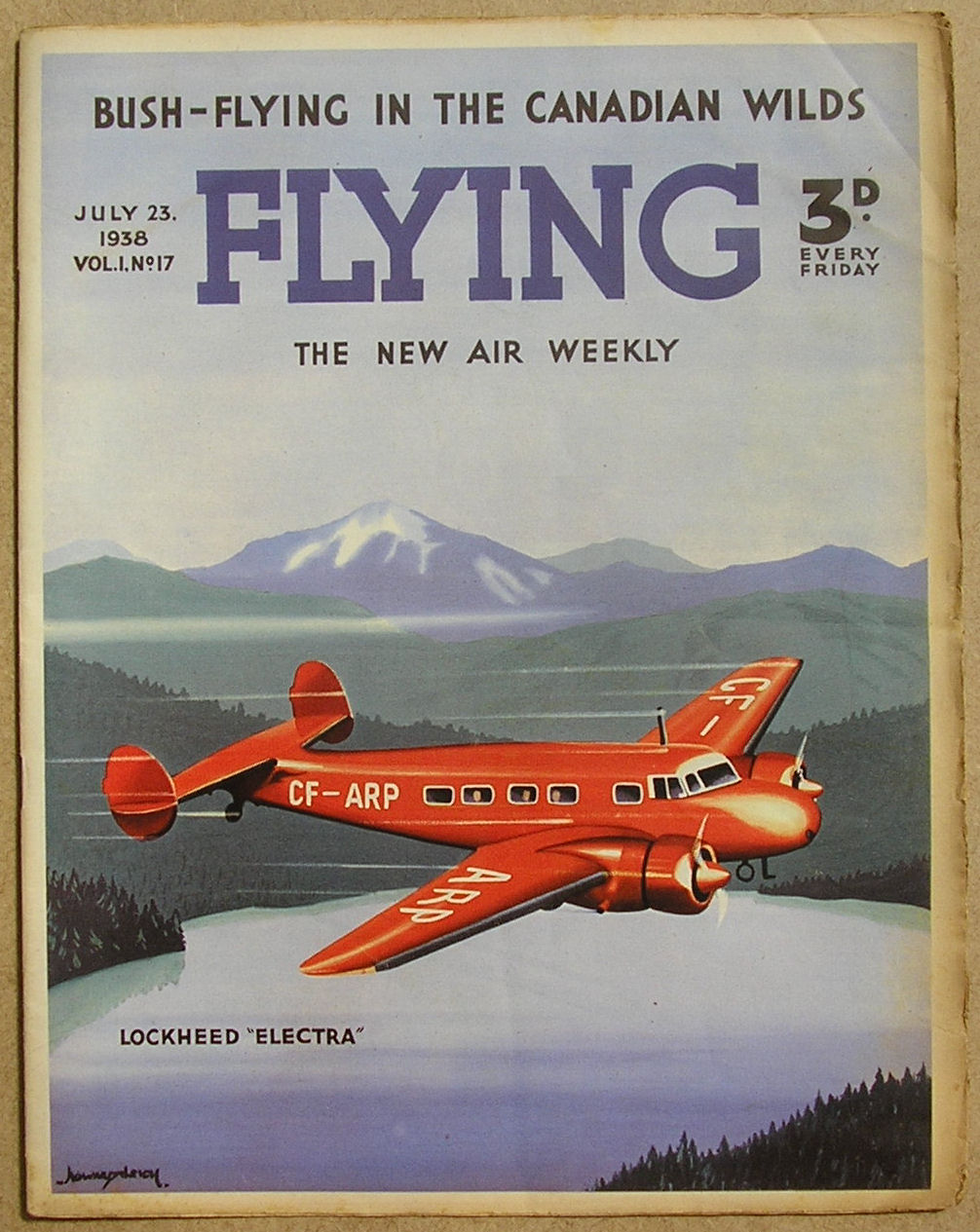

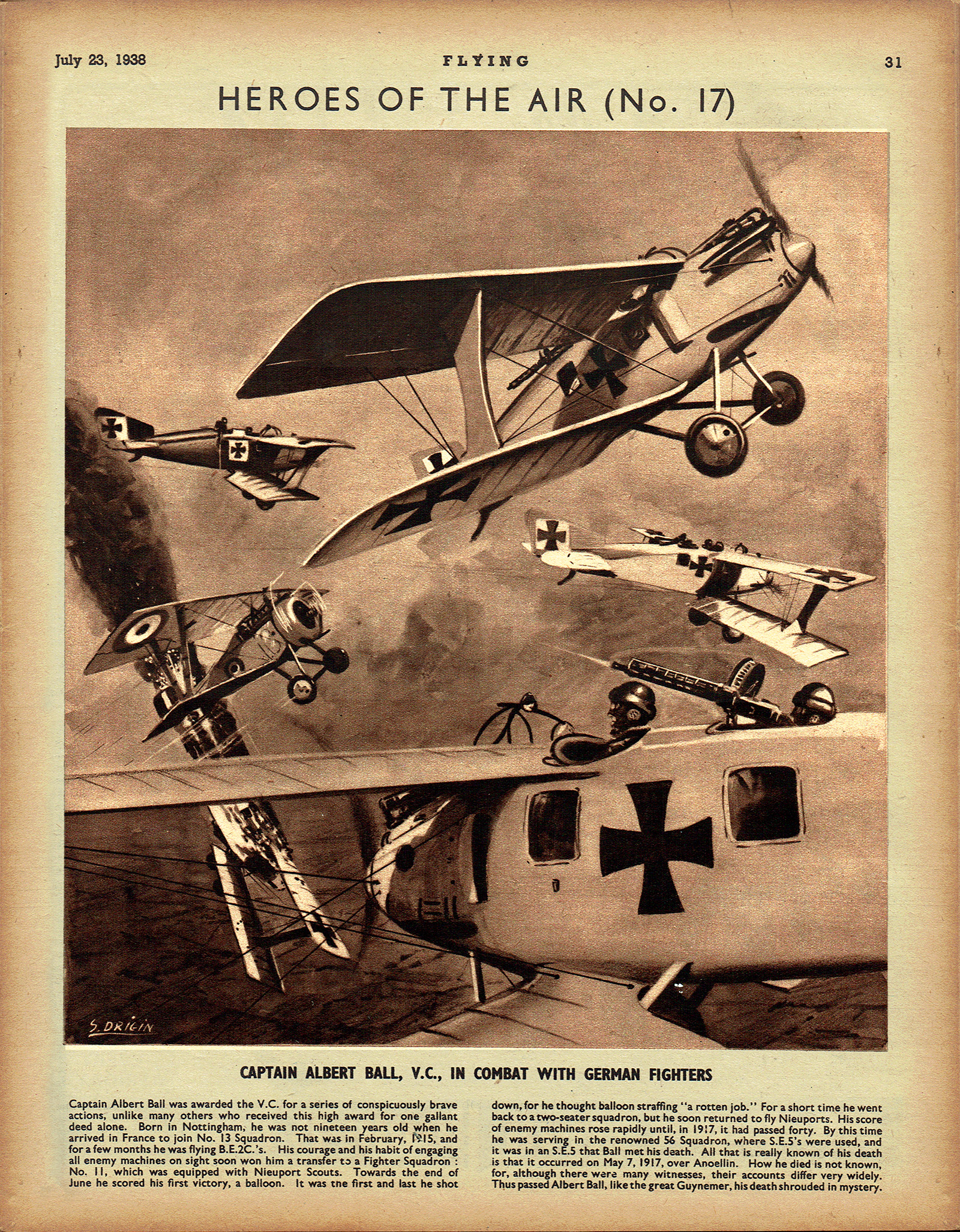

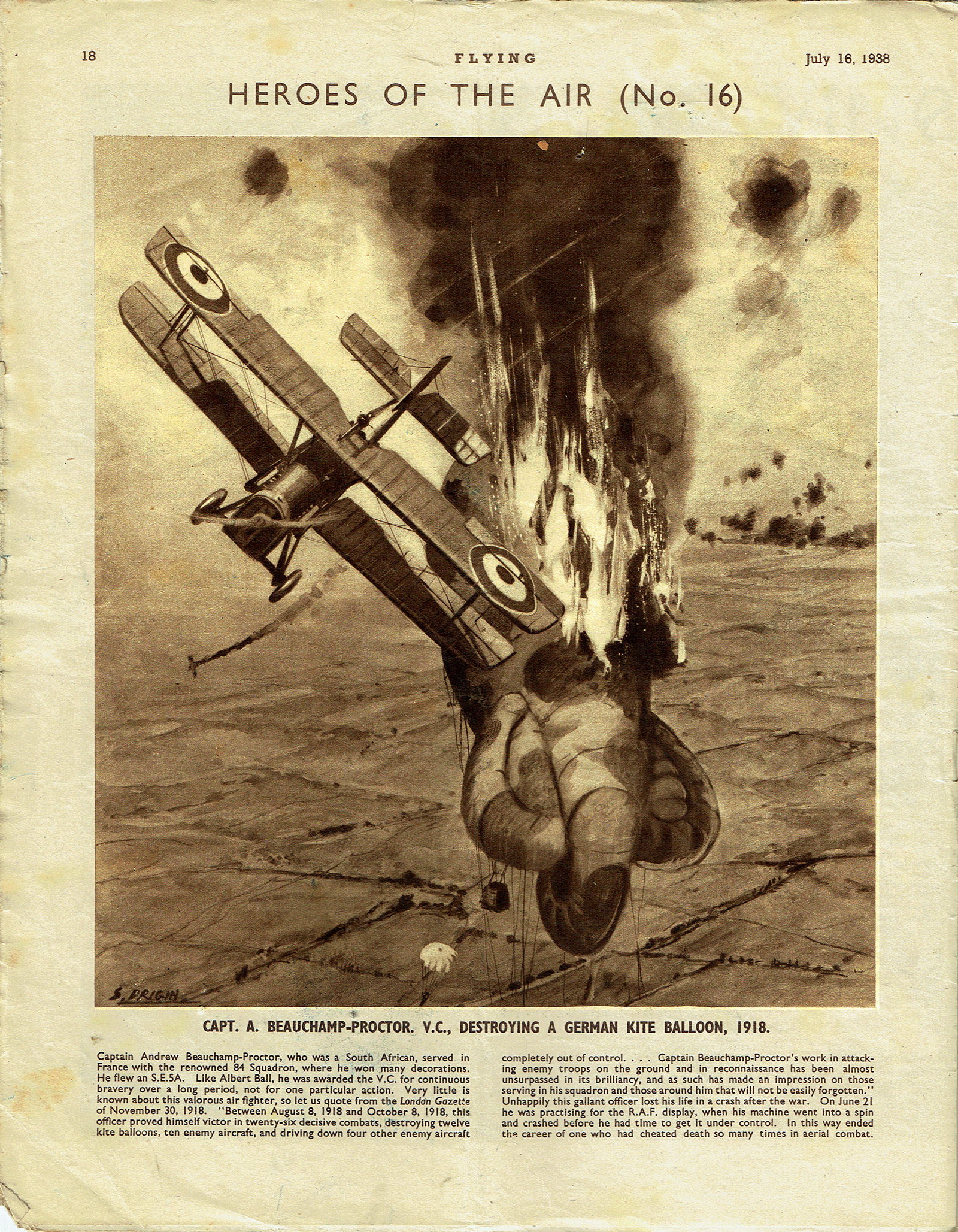

WITH the March Issue, WAR BIRDS changes it’s name to TERENCE X. O’LEARY’S WAR BIRDS and it’s focus. The lead story will now feature the exploits of Arthur Guy Empey’s Terence X. O’Leary, but the stories are more science-fictiony that O’Leary’s previous exploits in the magazine which were set in WWI. THE COCKPIT column continues with all it’s previous sections. And the coupon to join is still included. The Booklets can still be obtained for 5¢ and the wings are a bargain at 15¢. weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note. Today’s full page illustration is not an installment in that series, but rather tells the story of how Flight-Lieutenant G.E. Jackson won the Distinguished Flying Cross.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note. Today’s full page illustration is not an installment in that series, but rather tells the story of how Flight-Lieutenant G.E. Jackson won the Distinguished Flying Cross.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

to the squadron and he can’t stand pilots who “grand-stand” which is the Mosquitoes stock-in-trade and boy do they catch hell when they get on the C.O.’s wrong side—that is until the C.O. gets in a jam and it’s trick flying that’ll save him when the Boche attack!

to the squadron and he can’t stand pilots who “grand-stand” which is the Mosquitoes stock-in-trade and boy do they catch hell when they get on the C.O.’s wrong side—that is until the C.O. gets in a jam and it’s trick flying that’ll save him when the Boche attack!  weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

familiar to you, there may be a reason for that. The entire story was plagiarized from another. In this case it was Ben Conlon’s “

familiar to you, there may be a reason for that. The entire story was plagiarized from another. In this case it was Ben Conlon’s “

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.