“The Youngest V.C. Flyer” by Paul Bissell

THIS week we present another of Paul Bissell’s covers for Flying Aces! Bissell is mainly known for doing the covers of Flying Aces from 1931 through 1934 when C.B. Mayshark took over duties. For the August 1933 cover Bissell put us right in the action with…

The Youngest V.C. Flyer

SOME wise man has said that to every man, once in life, comes his big moment. Then he must make a quick decision or choice and, whether he be king or peasant, the real man is judged by how he meets this test.

SOME wise man has said that to every man, once in life, comes his big moment. Then he must make a quick decision or choice and, whether he be king or peasant, the real man is judged by how he meets this test.

Such a moment came to Alan McLeod, the young Canadian flyer. Always he was in the thick of it, eagerly taking chances, thumbing his nose at death until that day in March, 1918, when he came face to face with his big moment, made his choice and, himself wounded, gambled his life a thousand times over to save a comrade already wounded almost past saving—gambled and won, and took his place among the “Incredibles†of the World War.

McLeod was just fifteen years old when the war began. Twice rejected because of his youth, he enlisted on his eighteenth birthday, in April, 1917. By July he had qualified as a pilot, and by September he was in England. When his squadron, the 82nd, was ordered to the Front, his Commanding Officer refused to take him along—again on account of his youth.

However, on Home Defense in England with the 51st, during a bitter duel with a Gotha over London, he displayed such heroism, although shot down, that Headquarters posted him to France with the 2nd Squadron, in November, 1917. This squadron boasted no fast pursuit ships, but was engaged principally in observation, bombing, and artillery spotting, and flew the Armstrong-Whitworth, a good ship for these purposes, but slow.

It was with this ship that McLeod went “a-hunting†beyond and outside of his daily routine, strafing the trenches, attacking troops in movement, machine-gun emplacements and batteries. No one had ever thought to attack a sausage in one of the old crates. Nevertheless McLeod coolly destroyed a German balloon and then, when attacked by a flight of Albatross pursuit planes, shot one of them down and held the others off, returning safely to his airdrome. Soon none but the most daring observers would fly with him, but there were always enough of these so that he did not lack for companions. Besides, he always brought them back—and how!

The morning of March 22, 1918, seemed to McLeod much like any other day. With Lieutenant A.W. Hammond in the observer’s cockpit, he had started out on a patrol to Bray sur Somme. He got lost in the heavy, low clouds but, at last finding a hole, he had dropped down to let his bombs go when a Fokker tripe rode his tail down from the same clouds. A half-roll saved him from the Fokker’s burst, and a zoom put Hammond in position to prevent that particular German from ever firing another burst.

But seven other tripes had come down after their leader and were now bent on revenge. Like red hawks they darted around the two Canadians, raking them with machine-gun fire from every direction until one, more daring than the others, dived in from the front.

McLeod beat him to the shot and Fokker No. 2 joined his leader far below. At that instant, however, McLeod felt his first bullet. One of the tripes, attacking from below, had put a full burst into the British machine. Hammond was hit twice, and the entire bottom of his cockpit collapsed. Then the gas tank burst into flames. The Armstrong-Whitworth plunged down, out of control, with McLeod dazed in the front seat, and Hammond clinging desperately to the rim of what had been his cockpit.

THE flames licked up, burning McLeod back to consciousness. To stay in the front seat was no longer possible. McLeod stepped out on the wing, reaching back into the burning cockpit for the controls and sideslipping the plane so that the flames were blown away from Hammond. Although two more bullets had found him by now, he succeeded in keeping the ship in fair control and getting rid of his bombs. The Germans were following the helpless Canadians down, pouring burst after burst into them.

Hammond now had three bullets in his body, while one arm hung limp. Almost unconscious, with his feet braced against the sides of the fuselage to keep from falling through the bottomless cockpit, he still had strength enough for one last burst at the Boche. Almost point-blank he emptied his drum into the nearest tripe. A burst of smoke and screaming wires told that Fokker No. 3 had joined the other two victims, crashing below almost at the same instant that McLeod, leveling off his blazing ship as best he could, piled up in No-Man’s-Land.

The crash threw them both clear of the wreckage, about ten yards apart in the middle of No-Man’s-Land, three hundred yards from the British trenches. For an instant they lay there, unconscious, but the Germans were already sniping at them and McLeod, who lay in a more exposed position, was roused to consciousness by a bullet nipping his leg. Rolling into a shallow hole, his senses returned, and with them came his “big moment.â€

To stay where he was was impossible. The whole area was too much exposed. He must make the trenches. But outside lay Hammond, wounded, perhaps dead. Should he leave him and try for the trenches alone? In another instant he was out of the hole and at Hammond’s side. The poor observer was alive but completely unconscious, with six wounds.

How McLeod dragged and carried Hammond those three hundred yards he himself never knew. But the Tommies in the trenches saw him coming. They watched him as, inch by inch, he dragged himself and his observer across the torn earth, with the enemy raking him with bullets. They watched and helped all they could by laying down a deadly fire on the German trenches.

With just six yards to go, another bullet got McLeod, and the Tommies went over the top and dragged the two unconscious flyers in, still breathing—but not much more. All day they lay in those exposed trenches without medical aid. But the gods must have smiled, for they both got well eventually—Hammond to get a D.S.O., and McLeod the V.C.

“The Youngest V.C. Flyerâ€

Flying Aces, August 1933 by Paul J. Bissell

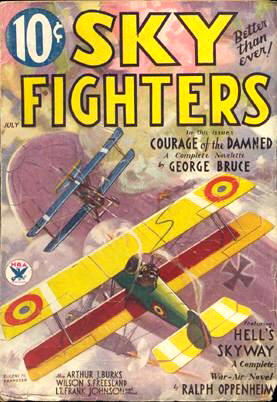

Mosquito Month we have a non-Mosquitoes story from the pen of Ralph Oppenheim. In the mid thirties, Oppenheim wrote a half dozen stories for Sky Fighters featuring Lt. “Streak” Davis. Davis was a fighter, and the speed with which he hurled his plane to the attack, straight and true as an arrow, had won him his soubriquet. And time is of the essence when Streak is sent on a bombing mission. He must destroy the Krupp Machine works at Luennes before they unleash German’s newest secret weapon at noon! From the July 1934 issue of Sky Fighters it’s “Hell’s Skyway!”

Mosquito Month we have a non-Mosquitoes story from the pen of Ralph Oppenheim. In the mid thirties, Oppenheim wrote a half dozen stories for Sky Fighters featuring Lt. “Streak” Davis. Davis was a fighter, and the speed with which he hurled his plane to the attack, straight and true as an arrow, had won him his soubriquet. And time is of the essence when Streak is sent on a bombing mission. He must destroy the Krupp Machine works at Luennes before they unleash German’s newest secret weapon at noon! From the July 1934 issue of Sky Fighters it’s “Hell’s Skyway!”

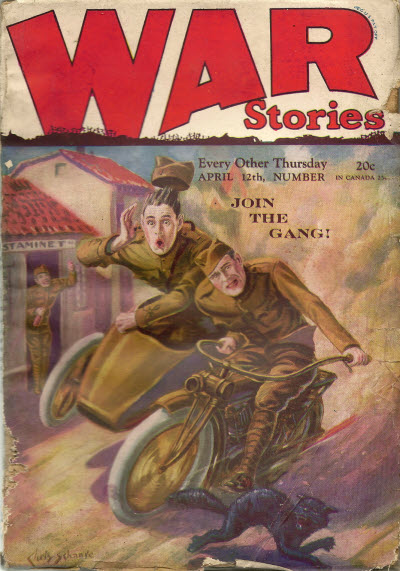

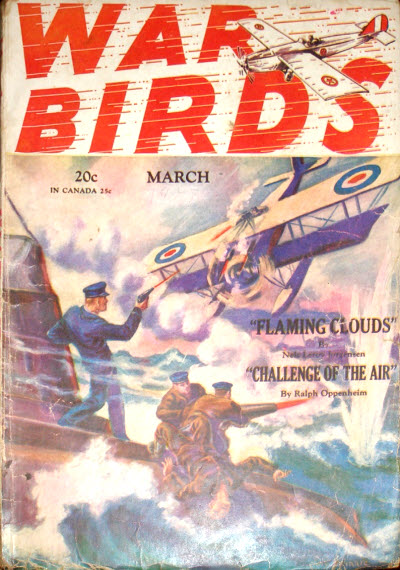

the third and final of three Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes stories we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! And this one’s a doozy! Kirby gets the unenviable job of test flying the new type Spad and putting it through its paces—including trying it in combat and shooting down a plane. But, under no circumstances should he take the new plane over the lines! Unfortunately that’s just what Kirby did! Read all about it in Ralph Oppenheim’s “An Ace of Spads” from the April 12th, 1928 issue of War Stories!

the third and final of three Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes stories we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! And this one’s a doozy! Kirby gets the unenviable job of test flying the new type Spad and putting it through its paces—including trying it in combat and shooting down a plane. But, under no circumstances should he take the new plane over the lines! Unfortunately that’s just what Kirby did! Read all about it in Ralph Oppenheim’s “An Ace of Spads” from the April 12th, 1928 issue of War Stories!

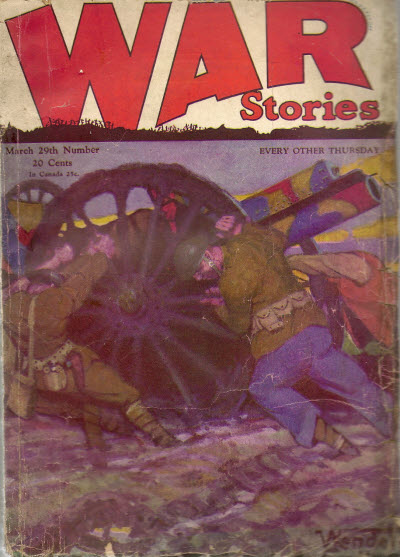

the second of three tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, the intrepid trio is tasked with getting valuable information from behind German lines—but it’s a job for only one man which unfortunately turns into one man at time as each of the Mosquitoes is sent off to garner the information when the previous one fails to return. From the March 29th, 1928 issue of War Stories, it’s The Three Mosquitoes in “An Ace in the Hole!”

the second of three tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, the intrepid trio is tasked with getting valuable information from behind German lines—but it’s a job for only one man which unfortunately turns into one man at time as each of the Mosquitoes is sent off to garner the information when the previous one fails to return. From the March 29th, 1928 issue of War Stories, it’s The Three Mosquitoes in “An Ace in the Hole!” hit the stands in February 1928, it not only contained an exciting tale of Ralph Oppenheim’s inseparable trio The Three Mosquitoes, but it also had a rare factual piece by Mr. Oppenheim. Ralph and his younger brother Garrett had taken a trip to Europe the previous year and just happened to be there at the right time to be able to get to Paris and be there at Le Bourget Field on the 21st of May when Charles Lindbergh successfully ended his trans-Atlantic flight!

hit the stands in February 1928, it not only contained an exciting tale of Ralph Oppenheim’s inseparable trio The Three Mosquitoes, but it also had a rare factual piece by Mr. Oppenheim. Ralph and his younger brother Garrett had taken a trip to Europe the previous year and just happened to be there at the right time to be able to get to Paris and be there at Le Bourget Field on the 21st of May when Charles Lindbergh successfully ended his trans-Atlantic flight!