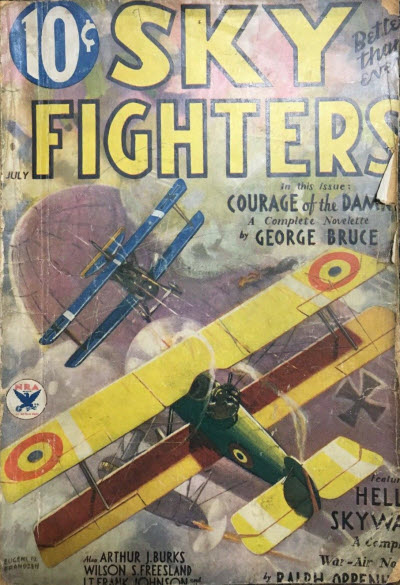

FROM the pages of the July 1934 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

Personal Gear

by Lt. Edward McCrae (Sky Fighters, July 1934)

DO YOUSE boys and youse goils remember the little ditty which goes:

The time has come, the Walrus said, to talk of many things,

Of shoes and ships and sealing wax, of cabbages and kings.

Anyway, I was sitting back in my study and looking at all the souvenirs hanging around on the walls and my mind got to wandering back to the days when we collected those scalps. Did you ever sit and let your mind wander and see just how it jumps from one unrelated subject to another? That’s the way I was doing.

More Than Cold Facts

I took a notion to jot down the things as they came to me, and when I got through I looked at what I had written and it just occurred to me that though they were interesting, most of them were in themselves of such little importance that people hadn’t written about them, but that on the other hand they were bits that go to fill in the chinks of war-air history. A kind of seasoning that makes the whole stew more intimate.

They make you feel like you have a more personal knowledge of flying than just the cold facts of airplanes.

Differences in Headgear

They’re the little personal touches. Like this:

Look at those helmets hanging on the tips of that propeller. Who has ever thought to mention little differences in headgear? Look at Fig. 1. First, there’s an old crash helmet. That is a German one. It looks like a mixing bowl. It is padded inside and has a padded rim around it. The leather is heavy—sole leather. You got plenty of crashes in those days and that old inverted bowl probably saved its wearer getting many a bump. It may have saved his life a few times.

And look at that “Gosport,” the one with the rubber tubing which runs from one helmet to the other. That was invented by an instructor who took the tubing from his air speed indicator and rigged up the helmet so he could give orders to his pupil. They’ve been standard training equipment ever since.

And look at that funny looking little gadget. Know what that is? It’s the upper end of a silk stocking belonging to the flyer’s best girl. It’s made into a skull cap to wear under the helmet at the right. It keeps your hair from getting soaked with motor oil and keeps your hair from whipping into tangled knots, keeps your head warm and brings you luck—if your girl’s true to you. If she’s not—better get another one from some other gal.

And the rag that’s tied to the top of the helmet in the left and stands out backward like a knight’s plume serves the purpose of wiping the grease off your goggles when they get blurred. Oil pipes are always cracking from vibration or being shot in two, and it’s handy to wipe hot oil off so you can see where you’re going.

Some Uniforms!

And that reminds me of the time when Ross came back to the field spattered with oil after a dog-fight and landed just in time to stand inspection by a visiting brass hat. Although we were attached to the British we had to wear the American type uniform at that time.

You had to wear a starched collar and the tunic had a stand-up collar. They jumped on Ross for having his collar unbuttoned. And Ross was plenty hot under the collar, anyway. So he risked a court-martial, and did he tell off that big bug about making men fly while being choked to death by a uniform.

It may be a coincidence, but Ross didn’t get into trouble for sassing a big shot, and it wasn’t long before we wore soft shirts, and still later the whole uniform was changed. A man can wear one now and not have his jugular vein sawed in two. See the difference in Fig. 2.

Ross just blew up and got off his chest a lot of things we were all griping about. We were Americans and proud of it, but we took an awful licking from the Brass Hats. The British were teaching us to fly and treated us like gentlemen. But our own big bosses figured we rated lower than dishwashers, apparently.

Them Was the Days—Nix!

They were against giving us commissions, and even took our flight pay away from us. That’s the way the army feels about flying. They object to there being a separate Flying Corps like the other major countries have. They want to run the flying show, but they want to handle it like they do the ground forces. That’s like trying to make a man a good swordsman by making him take pistol practice. You can’t make a good flyer by teaching him to march and stand at attention in a choker collar while the big shots strut in front of him.

But we made out in spite of our handicaps. We had to figure out a lot of tricks and do things the books don’t teach. Like the time Sprague had the magneto shot to pieces in his Camel.

We were in a bad way; couldn’t get replacements. And we didn’t have an extra magneto on the field. Sprague knew that a mag on a certain type German ship would do the work, so he went out and found a German and crashed him inside our lines and got himself a German and a magneto.

The Wonder Boy

Which reminds me of Sprague, the wonder boy. He was very young, but he’d been everywhere in the world and he made a specialty of being able to look out for himself. Earlier in the war he’d been shot down by a famous German ace, but that German, popularly credited with being a great sportsman, followed him down and kept pouring lead into him. The result was that he lost a leg just below the knee.

You’d think that would stop a man—but not Sprague. He pulled the wires some way and was back flying a ship with only one good leg. He had a gear rigged up on the rudder pedal so he could control it with one foot. Then while he was at it he went one better. He fixed up a little harness that attached to the stump of his leg and from that to the stick, and that boy could steer a ship with both hands free! He always carried a few hand grenades with him when he went out to fight.

Mystery Leg

But that wooden leg was the thing that had the whole western front puzzled. I knew him and got to find out about the mystery. It was just the length of his service boot which he had had built around it. When he got into his ship he would unstrap it and rig his leg to the steering apparatus. He ran up a lot of notches on his joystick in about this way. Germans, like the Allies, would try to get between the enemy and the sun, and then dive down on you while you couldn’t sec them for the glare.

However, you can hold your thumb up between your eye and the sun, so the sun is hidden by your thumbnail and you can see anything in the sky except it is directly in that small blind spot in front of the sun. But you can’t fly all day with your fist up in the air and staring at the sun.

What a Trick!

So Sprague painted a tiny black spot on one eye of his goggles, a spot just big enough to hide the sun itself, and with it he could keep a close lookout in the direction of the sun. Then he’d fly along in dangerous territory, but keep a sharp watch into the sun. A Heinie would dart down, figuring that Sprague would be unable to see him, and Sprague would fly along as though he didn’t know the German was coming—until the very last minute.

The German would be so confident of his kill that he wouldn’t be quite as alert as he should be. Poor Germans. More than twenty made that mistake before one of them downed Sprague, and made him a prisoner.

He Thought of Everything

And now back to the prison camp where they marched Sprague. And next morning Sprague was back with us! That boy thought of everything in advance. He couldn’t see any use in wasting all that space in that wooden leg of his.

The result was that it was a regular kit bag, fitted out for all purposes. When he showed me how he had hollowed it out and packed it, I saw, among other things, a small pair of wire clippers; a map of the sector we were flying in; some Swiss money in bills (Swiss because of their neutrality, and useful in case he had to escape from the interior of Germany and work his way back to French soil); a bottle of malted milk tablets; a flint and steel to light a fire; a tiny bottle of poison tablets; a package of Bull Durham smoking tobacco and papers, and a hand grenade!

That might sound to you youngsters—wipe your nose, Charlie—like a silly collection of things. But, as I said, Sprague was captured by a German—and was back home before morning.

Take a look at the list. See Fig. 3. He didn’t have to use everything in it, but you can see where he might have needed them. As it was, they threw him into a barbed wire enclosure with other prisoners to await transportation back into the main prison concentration camps. He cut his way out with the wire clippers under cover of darkness.

Swiss Money Useful

The map would have come in handy if they had carried him farther back of the lines. If they had carried him all the way to Germany and he had been able to escape, he would have tried to make his way to neutral Switzerland. He could have kept concealed, have built a fire with his flint and steel, to keep from freezing, he had emergency rations and even the makings of cigarettes. Having Swiss money, he could have bought things in places where they weren’t neutral because they all recognized Swiss neutrality.

And the bottle of poison? You never can tell in a war when perhaps death would be better than some of the things you have to go through—particularly if the enemy is trying to get information out of you that would spell disaster to your friends and your country.

Not Junk At All

And the hand grenade! You could blast your way out of a prison with one of those pineapples, or you could stop half a dozen men pursuing you. Sprague was partial to those little handfuls of explosive, and he managed to get them someway wherever he was, even though they weren’t issued to flyers. One time he did a loop over a man in a dog-fight and dropped one of the nuggets into the German’s cockpit. It rained tiny bits of Albatross and Hun for several minutes after that.

So, you see, you knot heads, that leg didn’t contain a junk shop after all. Most of us carried as much of that kind of gear as we thought we could hide—but we didn’t all have wooden legs. And so, sometimes, we were caught without some of these handy, all but essential, objects.

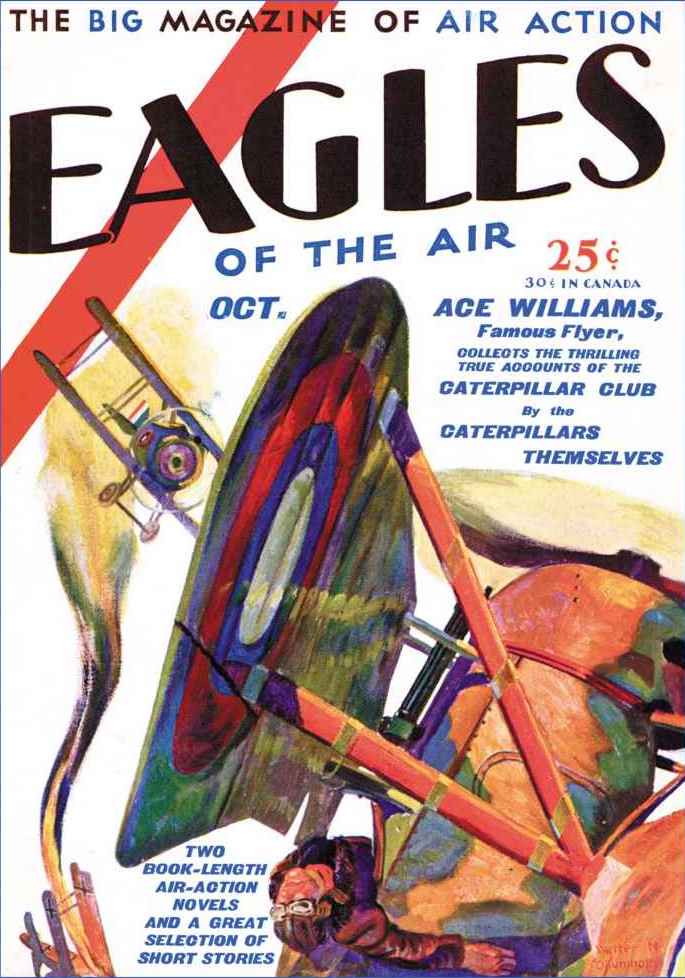

of three stories featuring D. Campbell’s The Three Wasps—stories plagiarized right from The Three Mosquitoes! So instead of the young impetuous leader Kirby of the Mosquitoes, we have the young and impetuous Gary heading up the Wasps. Similarly, Campbell changed “Shorty” Carn to “Shorty” Keen complete with briar pipe and eldest and wisest Travis to Cooper. This time we have their first of five appearances in Harold Hersey’s Eagles of the Air, a short lived pulp that didn’t even run a year. From October 1929 to August 1930, Eagles of the Air had nine issues; The Wasps ran in five of them.

of three stories featuring D. Campbell’s The Three Wasps—stories plagiarized right from The Three Mosquitoes! So instead of the young impetuous leader Kirby of the Mosquitoes, we have the young and impetuous Gary heading up the Wasps. Similarly, Campbell changed “Shorty” Carn to “Shorty” Keen complete with briar pipe and eldest and wisest Travis to Cooper. This time we have their first of five appearances in Harold Hersey’s Eagles of the Air, a short lived pulp that didn’t even run a year. From October 1929 to August 1930, Eagles of the Air had nine issues; The Wasps ran in five of them.

to the squadron and he can’t stand pilots who “grand-stand” which is the Mosquitoes stock-in-trade and boy do they catch hell when they get on the C.O.’s wrong side—that is until the C.O. gets in a jam and it’s trick flying that’ll save him when the Boche attack!

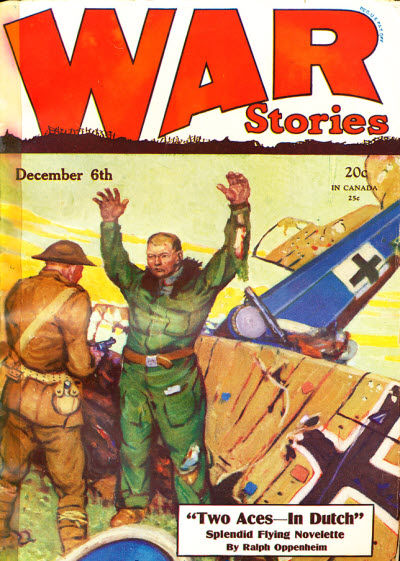

to the squadron and he can’t stand pilots who “grand-stand” which is the Mosquitoes stock-in-trade and boy do they catch hell when they get on the C.O.’s wrong side—that is until the C.O. gets in a jam and it’s trick flying that’ll save him when the Boche attack!  the third and final of three Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes stories we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! And this one’s a doozy! In a dogfight to the death, Kirby and the German Ace known as “The Killer” both end up going down—unfortunately, their fight had taken them off course and they have cashed in neutral Holland where both are taken into custody and are sentenced to remain in the country until the war’s end. The two bitter enemies in the air, build a fast friendship on the ground and must rely on one another if they are to escape and get back to their own squadrons! Read this incredible story in Ralph Oppenheim’s “Two Aces—in Dutch” from the December 6th, 1928 issue of War Stories!

the third and final of three Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes stories we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! And this one’s a doozy! In a dogfight to the death, Kirby and the German Ace known as “The Killer” both end up going down—unfortunately, their fight had taken them off course and they have cashed in neutral Holland where both are taken into custody and are sentenced to remain in the country until the war’s end. The two bitter enemies in the air, build a fast friendship on the ground and must rely on one another if they are to escape and get back to their own squadrons! Read this incredible story in Ralph Oppenheim’s “Two Aces—in Dutch” from the December 6th, 1928 issue of War Stories! the second of three tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, our intrepid trio hunt for the Invisible Ace!

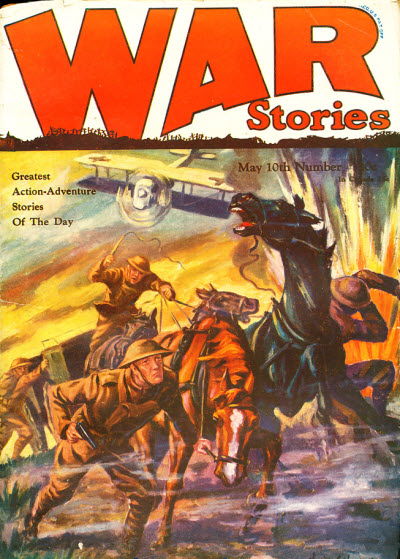

the second of three tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, our intrepid trio hunt for the Invisible Ace! off the ground with an early Mosquitoes tale from the pages of War Stories from January 1928! The enterprise was extremely dangerous, though simple. The Three Mosquitoes had been assigned to escort a flight of bombers that were to go across the lines to Staffletz, where, besides an important railroad junction, there were some Zeppelin sheds. The railway was to be damaged as much as possible, and then the machines were to ‘‘lay their eggs” on the Zeppelin sheds. Complicating matters—Kirby was flying in an unfamiliar, old Sopwith rather than his usual Spad!

off the ground with an early Mosquitoes tale from the pages of War Stories from January 1928! The enterprise was extremely dangerous, though simple. The Three Mosquitoes had been assigned to escort a flight of bombers that were to go across the lines to Staffletz, where, besides an important railroad junction, there were some Zeppelin sheds. The railway was to be damaged as much as possible, and then the machines were to ‘‘lay their eggs” on the Zeppelin sheds. Complicating matters—Kirby was flying in an unfamiliar, old Sopwith rather than his usual Spad!

another story from one of the new flight of authors on the site this year—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War and worked for the air mail service upon his return, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the 1920’s through 1950. Here Caffrey tells the tale of Lieutenant Paul Storm.

another story from one of the new flight of authors on the site this year—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War and worked for the air mail service upon his return, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the 1920’s through 1950. Here Caffrey tells the tale of Lieutenant Paul Storm. magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the

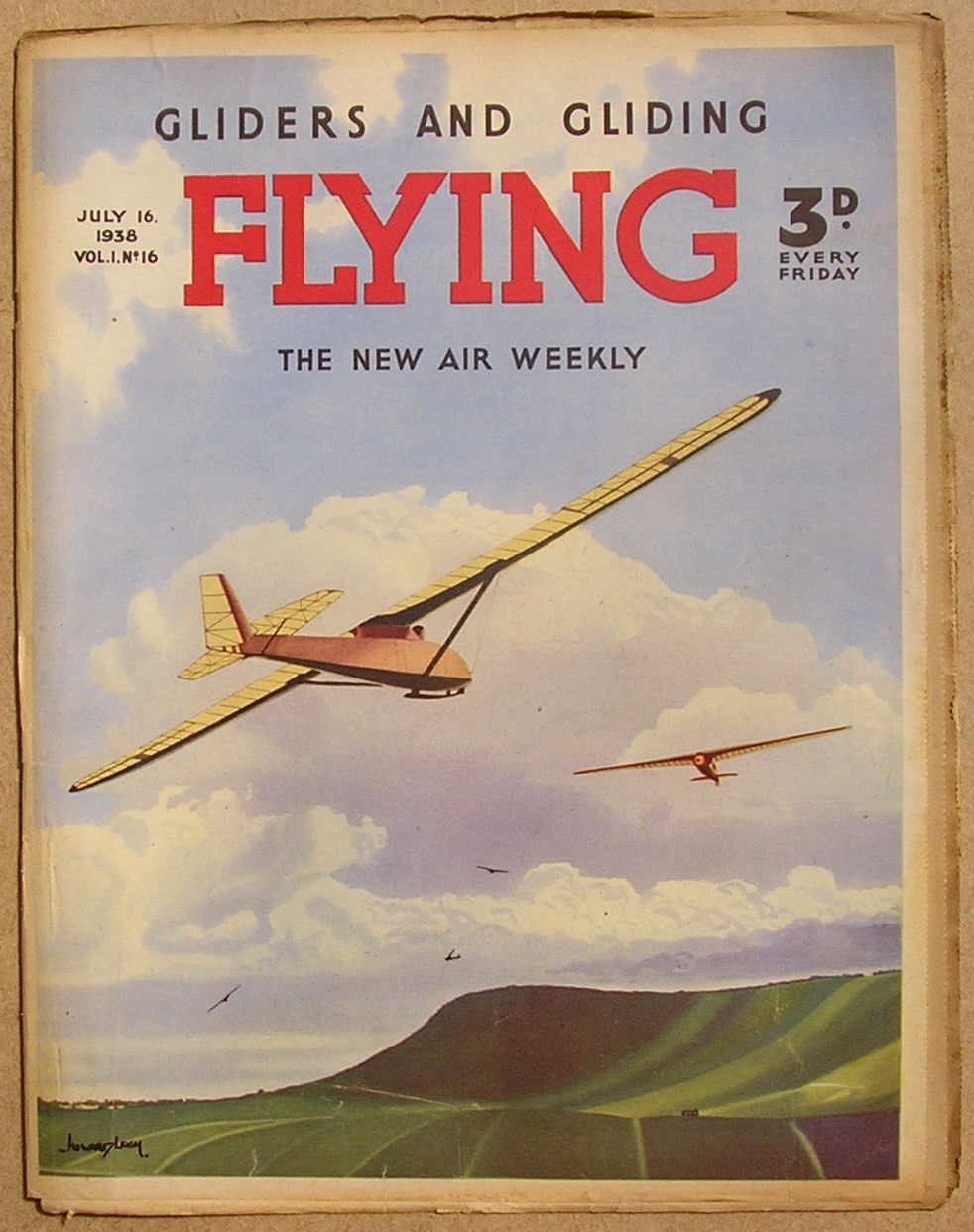

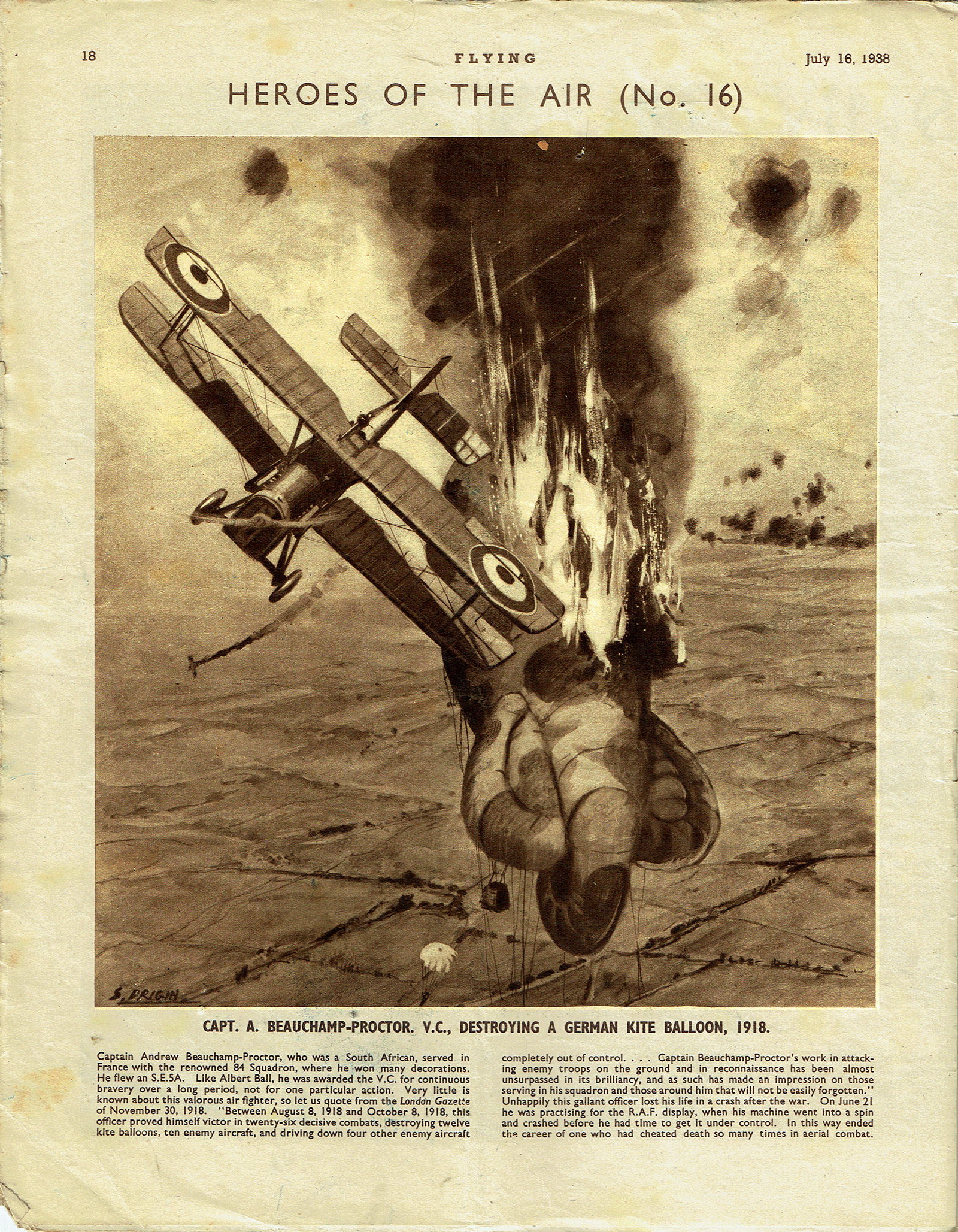

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the  weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

familiar to you, there may be a reason for that. The entire story was plagiarized from another. In this case it was Ben Conlon’s “

familiar to you, there may be a reason for that. The entire story was plagiarized from another. In this case it was Ben Conlon’s “

THIS month we’ve dragged another one of Air Trails’ pilot-writers out of his cockpit so that you folks can take a look at him. It’s hard to get these flying fellows to pose for their pictures. Most of them are so darned camera shy that you have to chase them all over the sky and shoot their props off before they’ll come down and act sensible. But sometimes you can catch them off guard.

THIS month we’ve dragged another one of Air Trails’ pilot-writers out of his cockpit so that you folks can take a look at him. It’s hard to get these flying fellows to pose for their pictures. Most of them are so darned camera shy that you have to chase them all over the sky and shoot their props off before they’ll come down and act sensible. But sometimes you can catch them off guard. That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

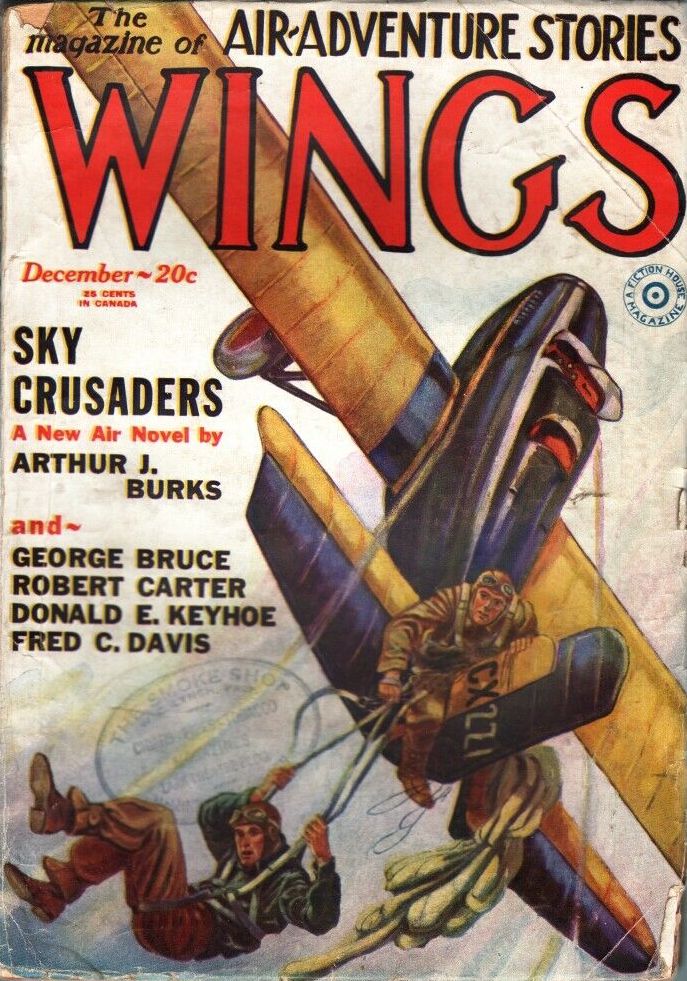

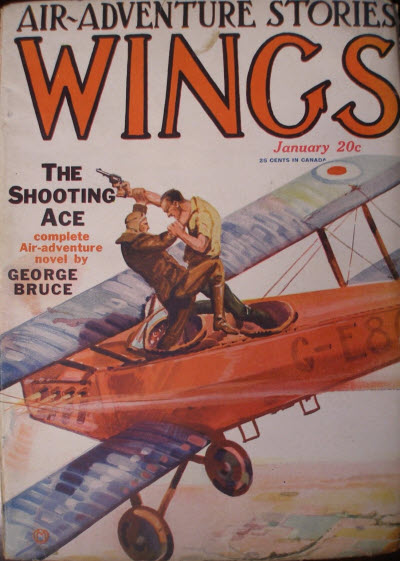

a short story by renowned pulp author Frederick C. Davis. Davis is probably best remembered for his work on Operator 5 where he penned the first 20 stories, as well as the Moon Man series for Ten Detective Aces and several other continuing series for various Popular Publications. He also wrote a number of aviation stories that appeared in Aces, Wings and Air Stories.

a short story by renowned pulp author Frederick C. Davis. Davis is probably best remembered for his work on Operator 5 where he penned the first 20 stories, as well as the Moon Man series for Ten Detective Aces and several other continuing series for various Popular Publications. He also wrote a number of aviation stories that appeared in Aces, Wings and Air Stories.