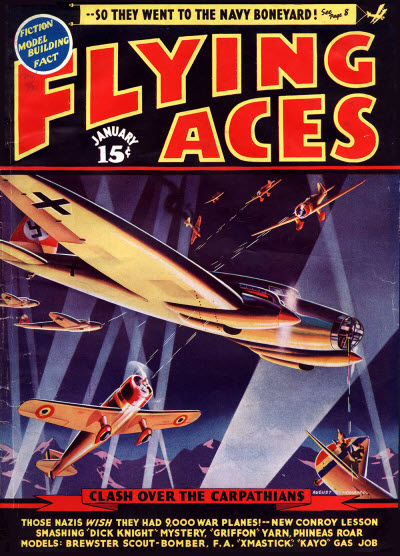

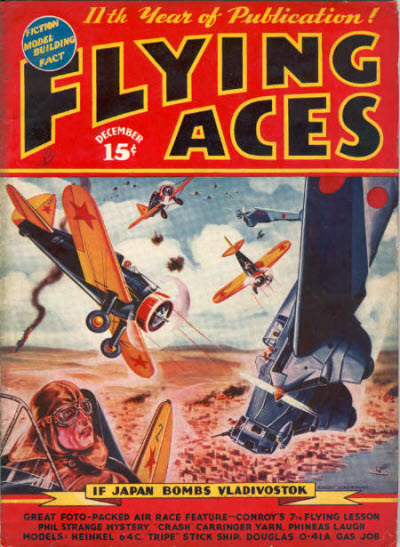

WITH the exception of that Bachelor of Artifice, Phineas Pinkham, Flying Aces stopped printing fiction with the September 1942 issue. Joe Archibald continued to chronicle the calamitous WWI exploit’s of Booneville’s favorite son for another year, when Flying Aces printed Pinkham’s last sojourn in the November 1943 issue. Joe Archibald had given Phineas Pinkham a good long run—surely the longest run of any of the WWI pulp pilots—running in the pages of Flying Aces from 1930 to 1943!

For a long time I thought that was it.

But then I started to see mentions here and there while reading articles about Joe Archibald of a post-war Pinkham. Now I didn’t know if there were actual stories or he just mentioned off hand what Phineas would be up to were he still going or even a flash forward in one of the later Flying Aces tales. That is, until I came upon the article below from the Port Chester, NY The Daily Item where it says categorically:

“. . . Joe recently resumed the character, only in the form of his son, “Elmer Pinkham, who is now ‘flying for wildcat airlines.’ ”

If this was true, where were these stories being printed? I checked all the sources at my disposal—the Robbins Pulp Magazine Index, the FictionMags Index website and any other reference book I could find, but none listed any further adventures past Flying Aces November 1943 tale “Sounds Vichy.” So the stories must have been published in a magazine not indexed by either of these two comprehensive sources.

Hmmm.

What if they were in Flying Aces, just later, after people had stopped indexing them. The article in The Daily Item was from May 1947, four years after Flying Aces stopped printing them. So I looked into tis and Flying Aces had a convoluted publishing history after Pinkham left their pages. Flying Aces was Flying Aces until April 1945. It changed it’s name to Flying Age (including Flying Aces) with the May 1945 issue. This change lasted less than two years! The December 1946 issue (v54n1) took on the title Flying Age Traveler! That lasted one issue. And it seemed it had possibly died with that concept change. . . .

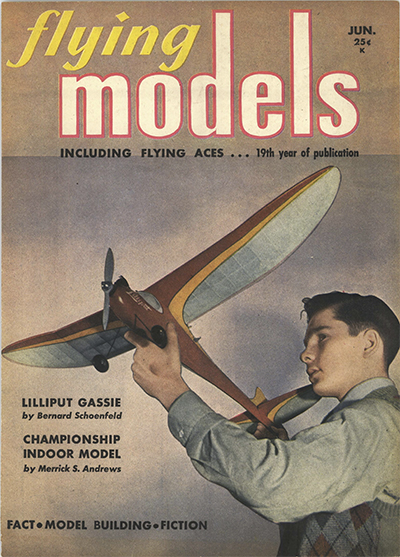

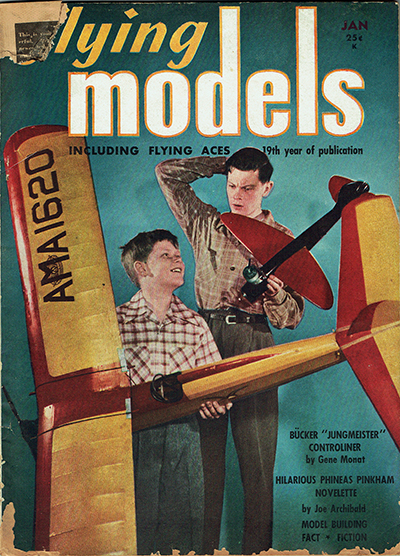

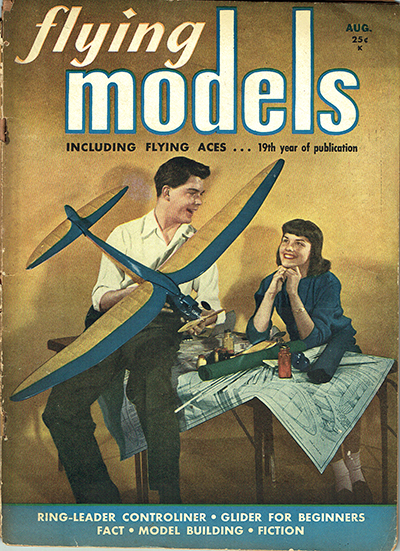

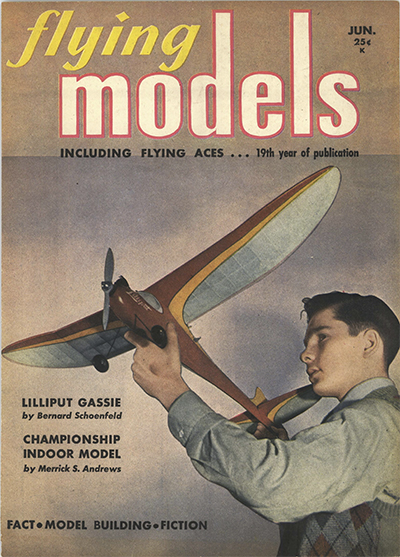

Six months later, in June 1947, the magazine was reborn as Flying Models with a number of the old staff on board. Some of the ideas they tried to bring back with the first issue was continuing the FAC (Flying Aces Club) and Phineas Pinkham!

Ah, there he was.

His red hair may have been greying at the temples and balding on top, and he may have added a spare tire to his physique, but it was still Pinkham. The new stories were set in the present day (post WWII) where Phineas, now married—not to Babbette, is now running a airline transport company called Flying Carpet Airlines—”We Fly Anything, Anybody, Anywhere! The Sky Is The Limit!”—with his son Elmer, a real chip off the old block (unfortunately), and with his old WWI mechanic, Terence Patrick Casey, keeping the repurposed DC3s in good shape. Phineas is also running a tricks and novelty company on the side making all the items he used to use to torment the Ninth Pursuits and many a German Von with during the Great War.

|

AN AGING PHINEAS PINKHAM gives his son a good what for.

|

History haunts the old man. There are mentions of his his wartime love Babbette, and his old C.O. at the Ninth Pursuits, Major Garrity—why his old hut mate Bump Gillis even puts in an appearance in one of the tales.

Sadly, it seems these new stories of Phineas Pinkham only ran in the first three issues of Flying Models. Brief as the run was, it was great to catch up with an old friend.

OVER the next few weeks,  we’ll be posting the three post war Pinkham stories from Flying Models Magazine. In this first story, Flying Carpet Airlines is engaged to transport a pair of corpses to Cleveland. Phineas hopes to get double duty out of the flight and hop a ride to Cleveland where he’s been invited by his old hutmate Bump Gillis to entertain at his Rotarian meeting, but runs into a little trouble with some spies on the way! From the June 1947 premiere issue of Flying Models, “Phineas Pinkham Flies Again!”

we’ll be posting the three post war Pinkham stories from Flying Models Magazine. In this first story, Flying Carpet Airlines is engaged to transport a pair of corpses to Cleveland. Phineas hopes to get double duty out of the flight and hop a ride to Cleveland where he’s been invited by his old hutmate Bump Gillis to entertain at his Rotarian meeting, but runs into a little trouble with some spies on the way! From the June 1947 premiere issue of Flying Models, “Phineas Pinkham Flies Again!”

Yielding to the demand of many thousands of flying model builders, Joe Archibald, personal historian of the famous Phineas Pinkham who singlehandedly almost lost the first World War for Uncle Sam, brings back Phineas in a new and hilarious series of adventures. Hail Phineas, Demon of the Blazing Skies, now chief of the Flying Carpet Airline, Inc., the biggest little trouble monopoly on wings in the USA!

As a bonus, here’s the article on author/artist Joe Archibald from the May 27th 1947 edition of Port Chester, NY’s The Daily Item that inspired the search for the post-war Pinkham stories:

6,000,000 Words Written And Sold By Joe Archibald, Town Resident

Leader In Civic Affairs Gives Facts About Varied And Interesting Career

by Alfred Feuer • The Daily Item, Port Chester, NY • 27 May 1947

|

AUTHOR-CARTOONIST-WHIRLWIND—Versatile Joseph S. Archibald of 48 Windsor Road, Town of Rye, takes time out from his literary pursuits to sketch himself at his labors. A plodding writer and one of the leading authors in the pulp market, Joe already has turned out in 18 years 6,000,000 words for magazines . . . and is still going strong. His sideline is cartooning, which he formerly did as a profession. Locally, Joe is renowned as an amusing master of ceremonies.

|

“Jake Carson, lolling in a luxurious parlor chair on the Southern Limited gazed abstractedly out of the window at the scenery rushing by.“

That line is the first fictional sentence in the writing career of Joseph S. Archibald of 48 Windsor Road, Town of Rye, who now has 6,000,000 words behind him, almost all printed in pulp publications. That opener comes from Mr. Archibald’s “The Black Tornado†and appeared in Complete Stories on Dec. 15, 1928.

Today, “Joe” Archibald, a man of featherweight physical proportions, stands among the foremost writers in the pulp class. (Typical pulp magazines are Argosy, Dime Westerns and Popular Detective).

This ranking reputation, which extends beyond American boundaries, pays off in substantial cash dividends. Mr. Archibald’s name is like a “blanche carte” in the writer’s world. The pulp editors snap up everything churned out in his typewriters. In fact, his supply is always insufficient. The editors are constantly pressing him for more and more stories.

Unlike many of his yarns, success stories in which the heroes struggle to triumph, Joe struck it rich in pretty quick time when he decided in 1929 to try his luck in the pulp market. He clicked easily. He was a natural tale-teller. Besides having the writer’s gift, Joe showed imagination. The fertility of his mind to conceive endless pieces for pulp readers’ consumption will probably never grow barren. He writes fluidly and productively.

Because he earns his livelihood by writing for pulps does not mean that Joe has molded his own character after any plotted by him on paper. As quickly as he pounds out his fables he tosses those characters completely from his thoughts.

Joe Archibald is his own rugged, vigorous self. He thinks and acts independently. He has already left an indelible mark on local history. There is no doubt that many people consider him a “character.” True, indeed, but he’s a character with good sides: he’s serious; he’s funny; he’s honest and he believes deeply in the practices of democracy. Those traits are seldom associated with guys know as “hacks†among writers.

His Ideals

His personal philosophy is gradually beginning to overrun on the pulp soil he has successfully nurtured during the past 18 years. He thinks books will relieve the flow. They will afford him a solid opportunity to break away from pat, dreamy formulas. In a book he can develop his own stored-up fundamental ideals.

Joe is already a book author. He completed his second (the first was a western tale) hard cover volume several months ago and expects to have it published in the Fall by the Westminister Press in Philadelphia. A story about football, he aimed it at youths from 12 to 20 years. Although it bears a prosaic title, “The Rebel Half Back,†its theme has enough meat and substance to push strongly its sales.

Mr. Archibald wrote the story after a study of boys’ books. He concluded that “boys’ books are not up to par and need a higher fictional standard.†He has been in touch with new writers also lapping these literary resources and learned that they are “starting a writing revolution of young people’s books.†These writers, Mr. Archibald revealed, are showing the proper respect for youngsters.

“Children today are getting more credit for their intelligence,†he asserted. “I feel that the field for writers who understand youth of today is wide open and untapped. There’s a ready market for those authors who understand and recognize the problems of youngsters.â€

To Joe the problems are basic post-war ideals. He has, he said, expressed those views in “The Rebel Half Back.†He used the gridiron as a backdrop—a smart notion because football is loved by all boys—to talk about equality and liberty for all. In his opinion the boys are currently more thoughtful about relationships between all peoples. I’ve lashed out at intolerance and discrimination,†he said strongly. “Everyone should have a fair chance on every plane. There is absolutely no room in our country tor bigots and bigotry.â€

“Our biggest fight today is against the evils that precipitated the last two wars. The symptoms are still here—two years after World War II—right in our very midst. I believe in judging a man by what he is, not who he is.â€

These feelings guide Joe’s choice of friends. He enjoys companionship for their friendship value; quality of character is his measuring rod. He mingles with all sorts of men who meet his standards and finds that they make life thoroughly appetizing.

Not surprisingly, Joe’s fame rests on his talent of amusing people. In the pulp world he is reputedly rated as the standout humorist. He revels in writing stories with comical twists. He said he has composed “more popular humor for pulp than any other writer.â€

Served Red Cross

His most famous character ever created was “a pre-war chap who turned out to be all funny-bone.” Joe tagged him “Phineas Pinkham.†The fictionalized comedian made such a hit among Joe’s thousands of young fans that Phineas grew into a national figure. Clubs were named for him, and radio stories were built around him. While Joe was in the European Theater in 1945 serving with the American Red Cross he was often questioned about Phineas Pinkham by many American Army officers. They told Joe that they could never forget Phineas who, as a World War I Army flier in the Archibald vein, was “an absolute scream.†Through these reminiscences of war-experienced veterans, Joe recently resumed the character, only in the form of his son, “Elmer Pinkham, who is now “flying for wildcat airlines.â€

Joe’s in heavy demand as an entertainer in these parts. He has built up a following among local clubs anxious for diverting evenings. His fresh and funny patter please his audiences immensely. (For years in New York City he was a leading master of ceremonies at writers’ gatherings. He tired of the pace and routine of such functions).

Besides being able to make people laugh at his gags he also amuses them by his ability as a cartoonist. This versatile stroke is no new tack in his bag of tricks.

Joe’s first vocational love was cartooning. He worked in 1925 for the now-defunct Wheeler-Nicholson Syndicate in New York, drawing features that were circulated among 150 newspapers, then the firm was absorbed by the McClure Syndicate. For McClure Joe (whose early strips cover the walls in his second-floor corner-room work den) turned out sports and science panels; the latter strip he called “Outline of Science.”

In 1927 he quit the syndicate concern to join the ill-fated New York Evening Graphic. (He worked with Port Chester’s Ed Sullivan on the Bernarr MacFadden tabloid; also with Walter Winchell). He sketched the first gangster strip in America, “Story of Steve West.” His faith in cartooning disappeared when the Graphic collapsed and he turned permanently to pulp writing to earn his board and keep. Despite this switch he has not forgotten how to splash deft strokes on his easel board. Cartooning gives him an outlet to relaxation. Joe said he abandoned cartooning because few cartoonists attain independence. Pulp writing has given him that privilege and luxury.

Joe says he can’t find any hereditary link of his career. He is the only one in his family with a literary or drawing streak. He was born on his father’s dairy farm in Portsmouth, N.H., on Sept. 2, 1898. (His parents are still on the farm; his father has retired in favor of a brother of Joe).

Served In Navy

He attended for one year the University of New Hampshire (known then as New Hampshire State College). He left the school in 1917. He had begun to display skill with pen, brush and palette. He registered at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts to study art techniques and cartooning. Meanwhile, the first World War was rumbling in America. He dashed from the academy to Kelly Field, Texas, to try to become an air cartographer. But his parents, who objected to his military ambitions, scotched that plan. His mother and father ordered him home.

He didn’t stay long on the farm. Patriotism gnawed inside him and he enlisted in the Navy in August, 1918. Two years later he was discharged as a Chief Petty Officer. While in the Navy he had his first opportunity to try cartooning; he was on the staff of a Navy publication, “The Newport Recruit.” That experience sharpened his yearning for further training at the Chicago Academy in which he re-enrolled in 1921.

He stayed there long enough to get his art degree. But he didn’t get a chance to utilize his Fine Arts study in his first job. He was hired as a police reporter by the Boston Evening Telegram. Joe must have kept the editor in good spirits because he was allowed to conduct a humorous column, “Blaze Trails.†Twenty months later the Telegram folded. The Boston Post picked him up as a police reporter. He tired of this assignment after six months and repaired in 1924 to New York City where he tied in with the Wheeler-Nicholson outfit.

He hopped into fiction late in 1928 when he discovered that he could concoct and sell stories. He collected $200 for his initial product. a fight yarn. Since then he has knocked out 6.000.000 words. To get a comparative idea of that tremendous wordage output “Gone With The Wind.†regarded as one of the longest novels of all-time totals a skimpy 150,000 words.

At present he supplies stories to several monthly magazines, including American Eagle, Popular Detective and Western Trails.

Salaries for good “name†pulpers range from $7,000 to $20,000 a year. In this game, where magazine owners pay off by the word, volume and production count most, he said. However, from year to year an annual stipend is not guaranteed, of course. He had his best year in 1931. Occasionally he has illustrated some of his own yarns, but he does not care for this combination. He never reads his published stories; he says he hasn’t got the patience for this indulgence. Mr. Archibald has had several stories printed in Collier’s magazine, but has not yet passed the acceptance line of the Saturday Evening Post.

Has Many Avocations

He reports that during his span he has written for at least 300 publications, all fictional. His byline has always been “Joe Archibald.†He stopped saving his voluminous published products years ago, otherwise he “would have been forced to move out of the house.”

He does most of his writing in daylight hours, from 9 A.M. to 4 P.M. He holds pretty fast to this schedule. All writers must have a time system to enable them to develop the daily writing habit. A hobby, he advises novices should also be part of the daily diet. His avocations are painting, gardening, entertaining and civic affairs.

Tries Politics

He took a shot on May 6 at a semi-political office—trustee of the town’s Board of Education—and was licked. He has vowed never to attempt it again. Right now he is indirectly involved in national politics. He drew up the brochure for the Young Republican National Federation to be held in Milwaukee on June 6, 7 and 8. (Ralph Becker of Port Chester is chairman of the national group).

In 1928, Mr. Archibald and Miss Dorothy Fenton of Port Chester were married. He lived in the Village for years until he erected his own dwelling on Windsor Road, ten years ago. Although he resides in the Town of Rye, he still prefers Port Chester. “The advantages are there,” he said. “We use all the Village’s facilities.”

He dabbled as a radio writer but abandoned the networks because of the comparatively low remuneration and the disagreeable working conditions. “Radio writing will drive the average man out of his mind if he stays at it too long,†he believes.

One of the main fortes of a writer, he contends, is to be a good judge of character and to be able to study and diagnose people. Joe Archibald likened the writer to a newsman, in the sense that their respective minds are always absorbed in stories.

He urged men and women who are anxious to hit the pulp market but can’t produce 3,000 words of finished copy daily to find another groove. “You can’t make a living at it otherwise, he counseled.

He made an interesting contrast between writers for pulp magazines and for “slick” publications (examples are Colliers and the Post). Pulpers concentrate on plot and action, and slick writers rely on characters and mood, he says.

When reading fiction he tends to stories loaded with color and action; when he selects non-fiction he chooses philosophy and psychology. He detests crime tales. “I can’t read who-done-its. They’re all alike, and so farfetched. All of the who-done-its today are long-winded and contain junky dialogue; far too superfluous.â€

His writing commitments prevent him from taking vacations of any length. “I have too many deadlines to meet and I have to keep close to the market,” he commented. “And don’t forget that ideas don’t often come in a hurry.”

Banging out 6,000,000 words has taken its toll of his typewriters. Mr. Archibald has already had to replace four machines. He always keeps two typewriters in his home. Another standby in his den is an easel on which he does his sketching and painting. He goes in for still life in water colors. He has had his canvasses on display at an exhibition conducted by the Port Chester Fine Arts Society. Many of them are mounted and adorn the walls in the Archibald residence.

In the town and the Village his friends consider him an inveterate cigar smoker. Cigar-smoking has not contributed to his writing technique, and he would not recommend cigars “to authors or anyone else.”

Be sure to come back next Friday for another Post War Pinkham story!

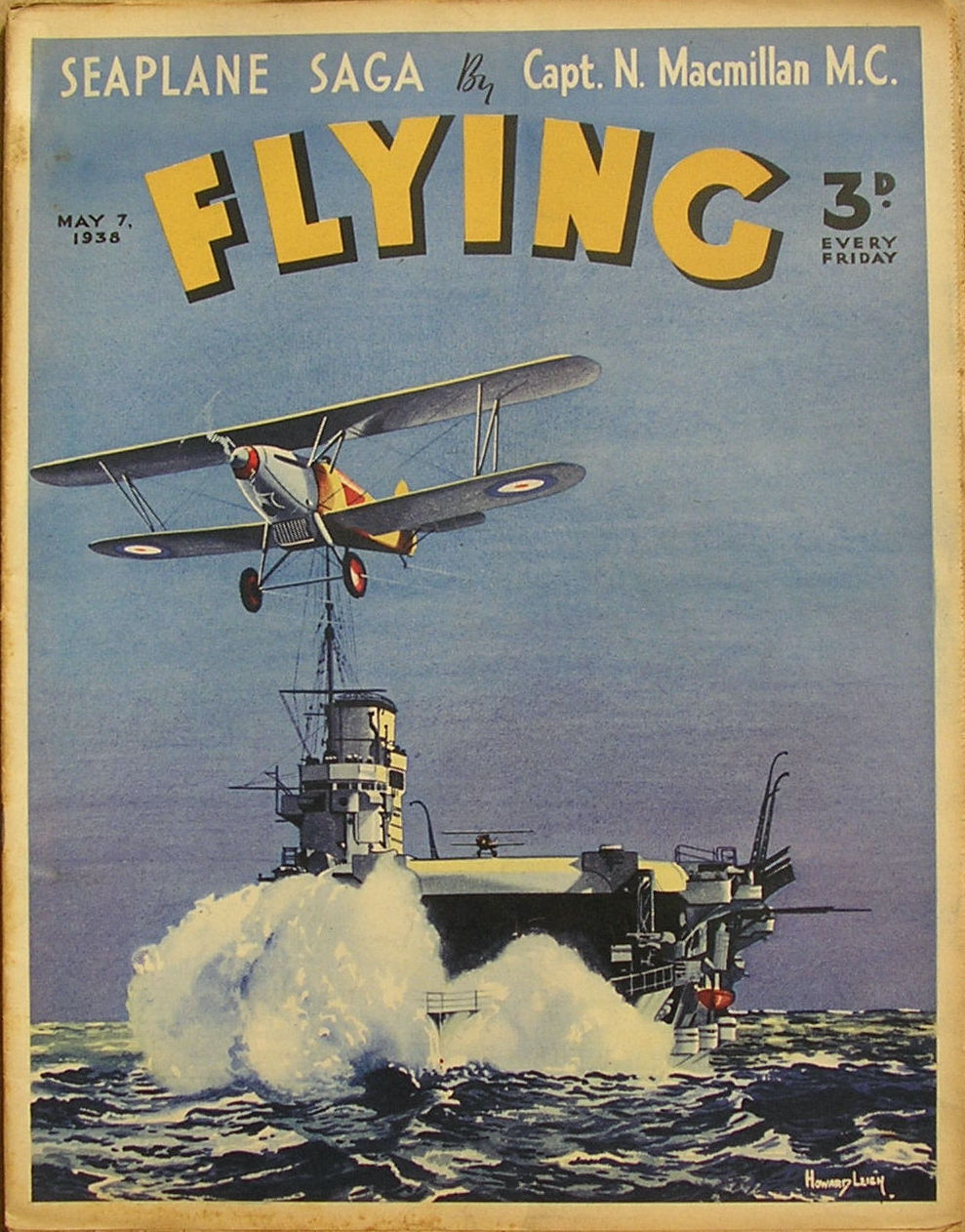

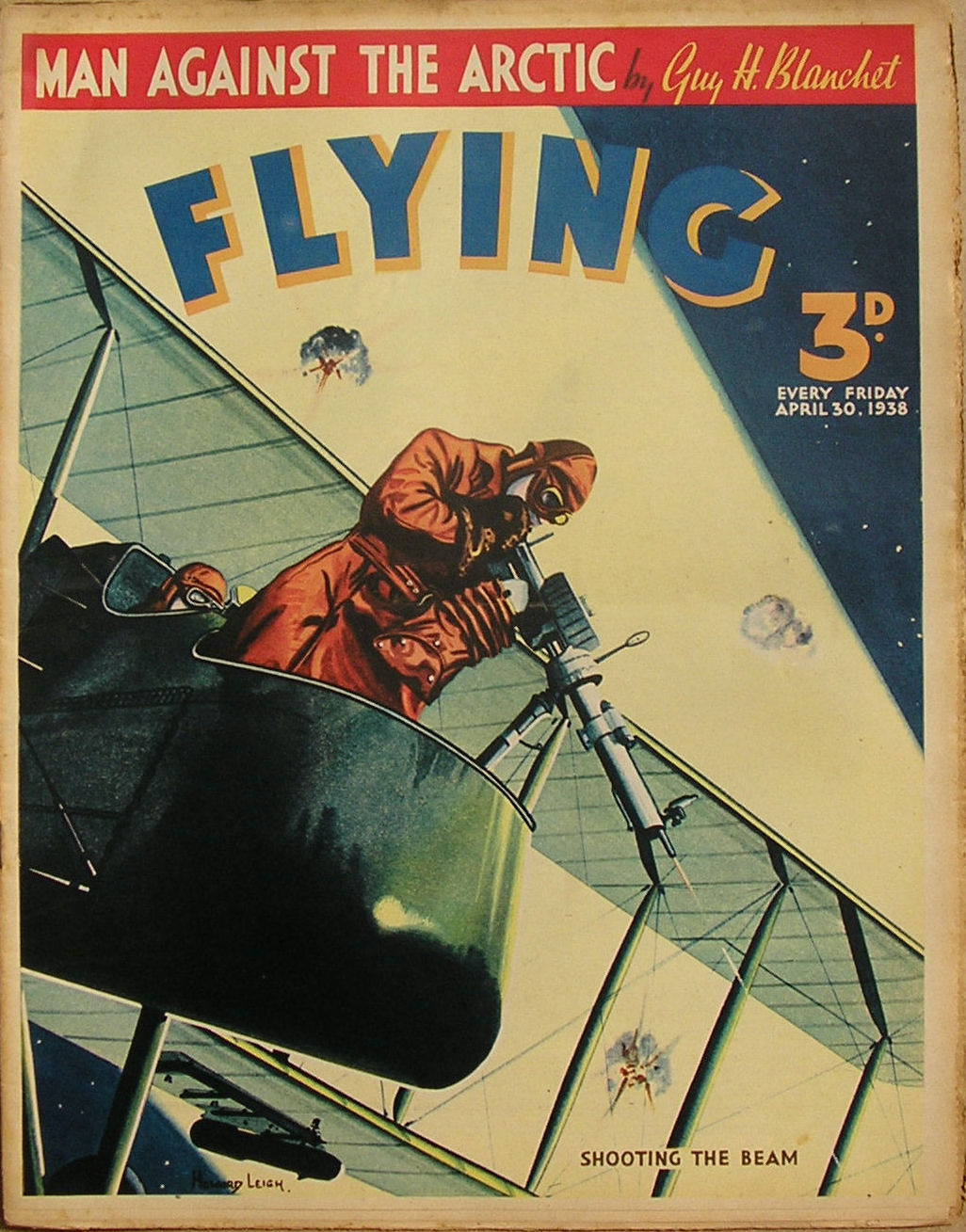

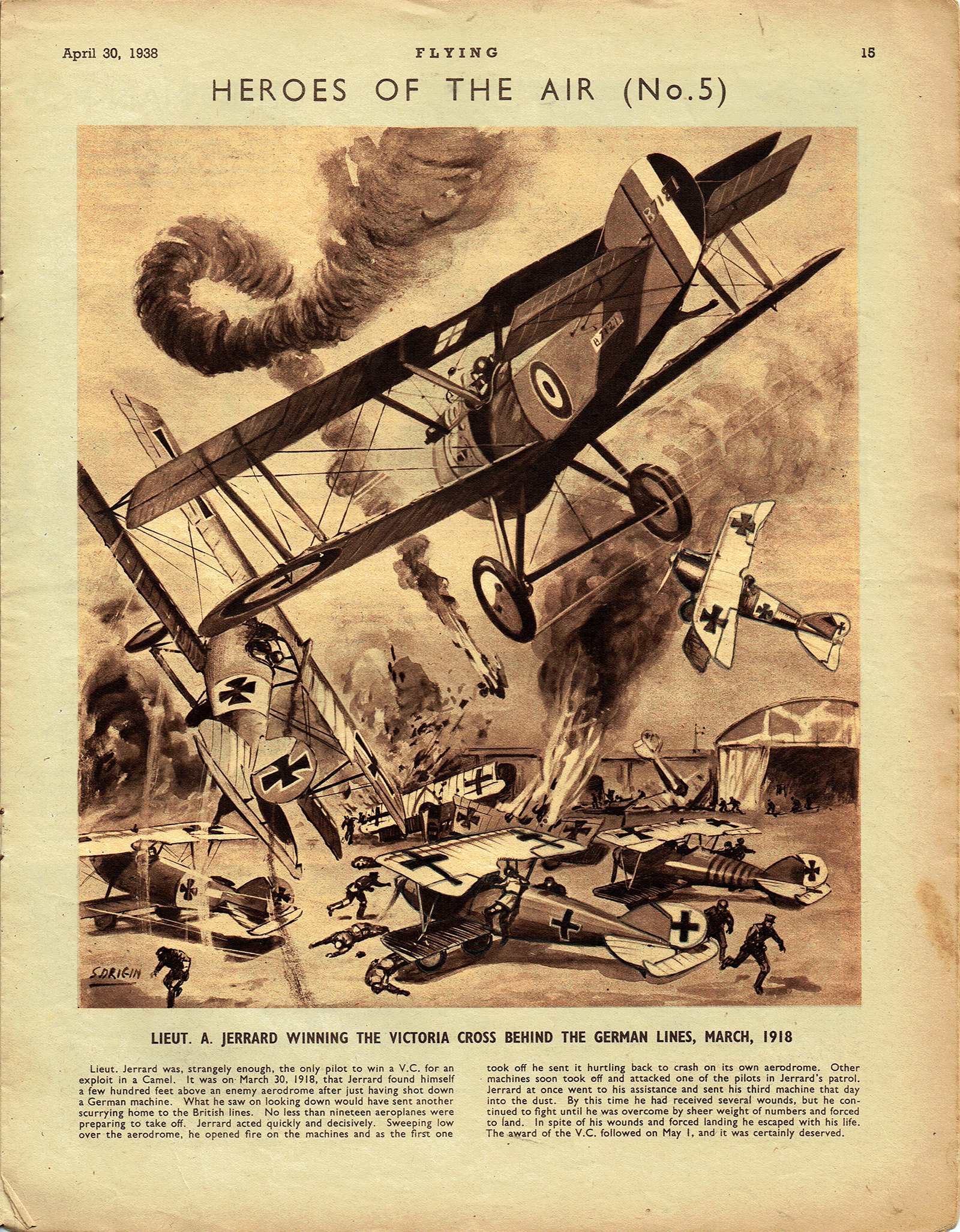

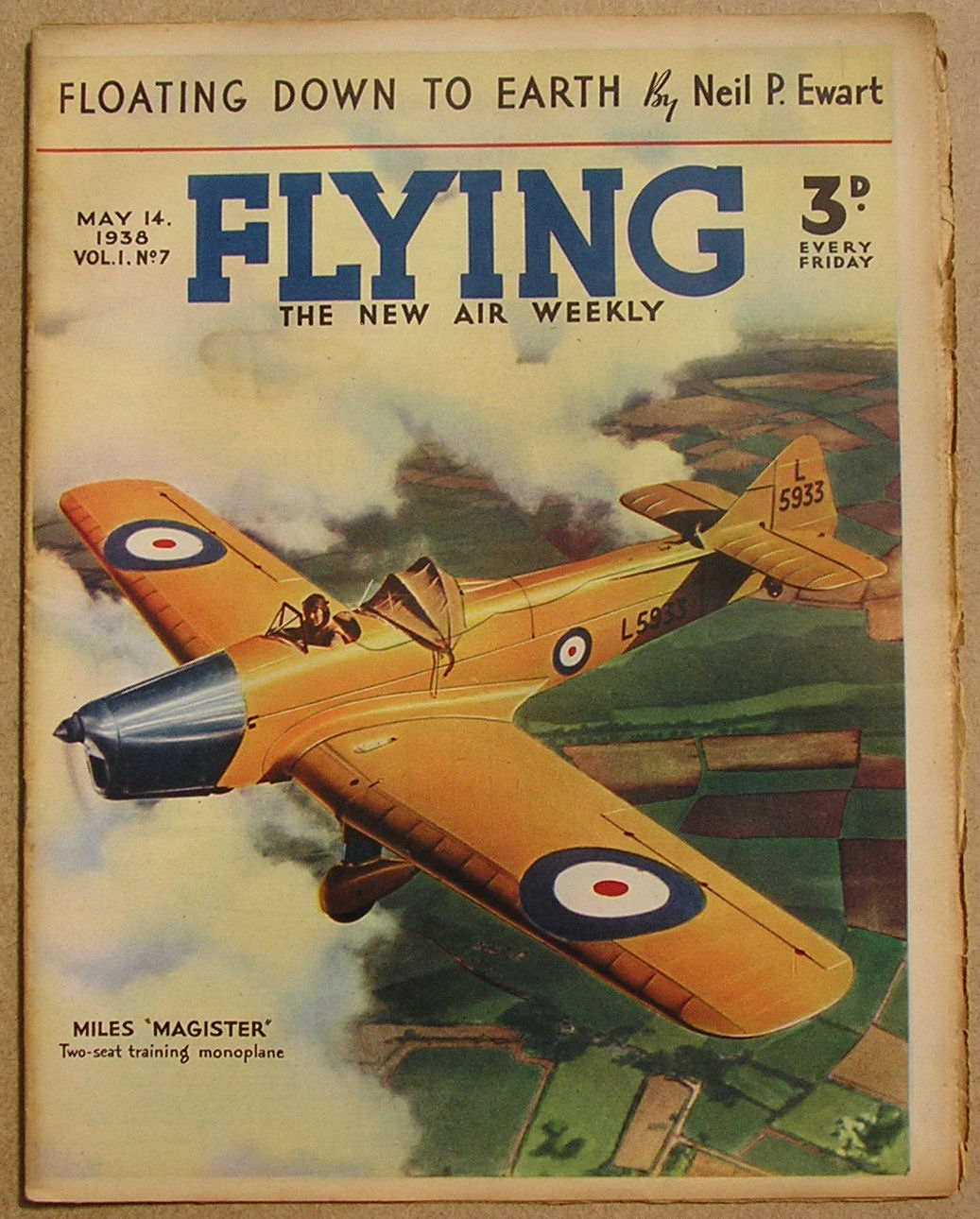

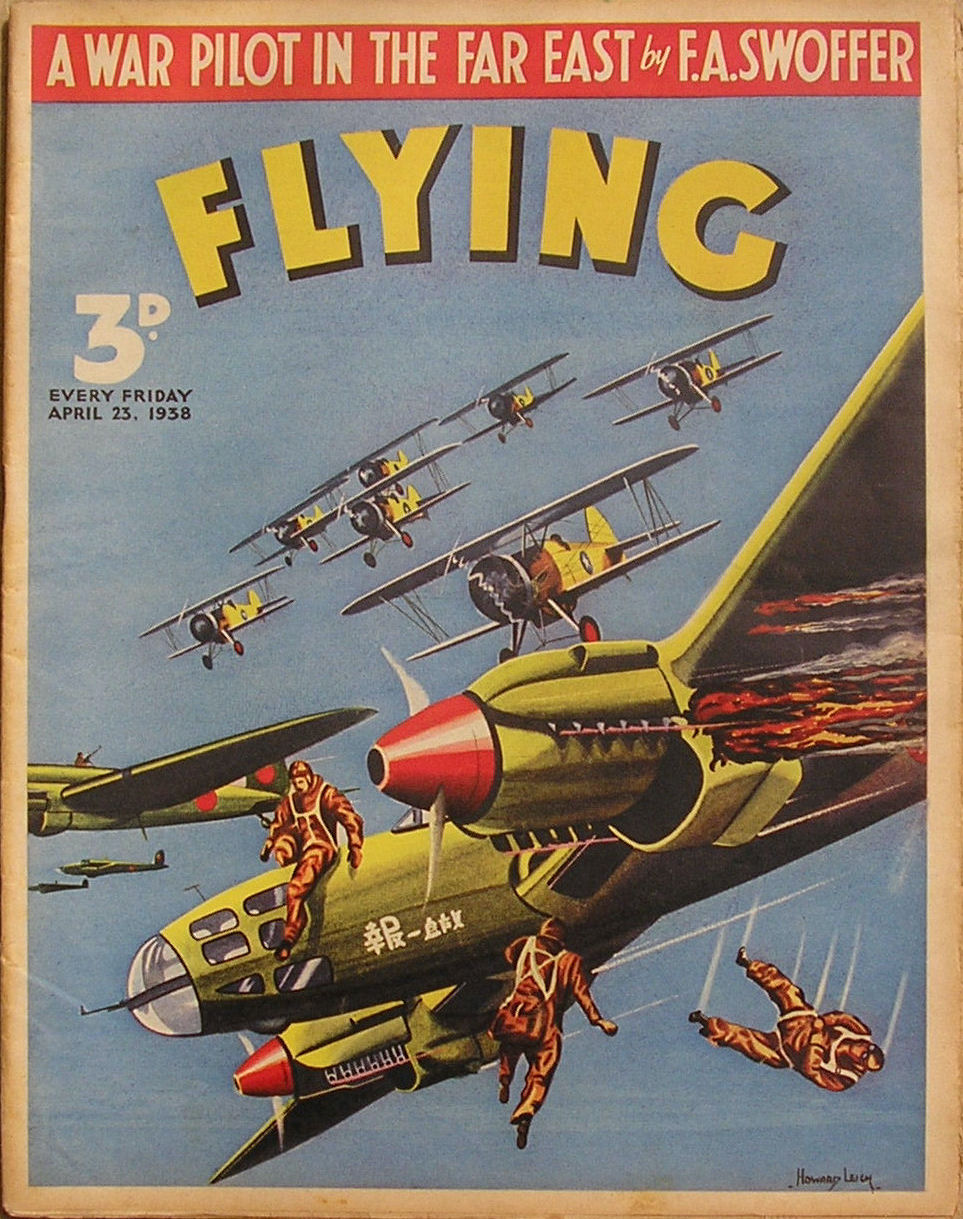

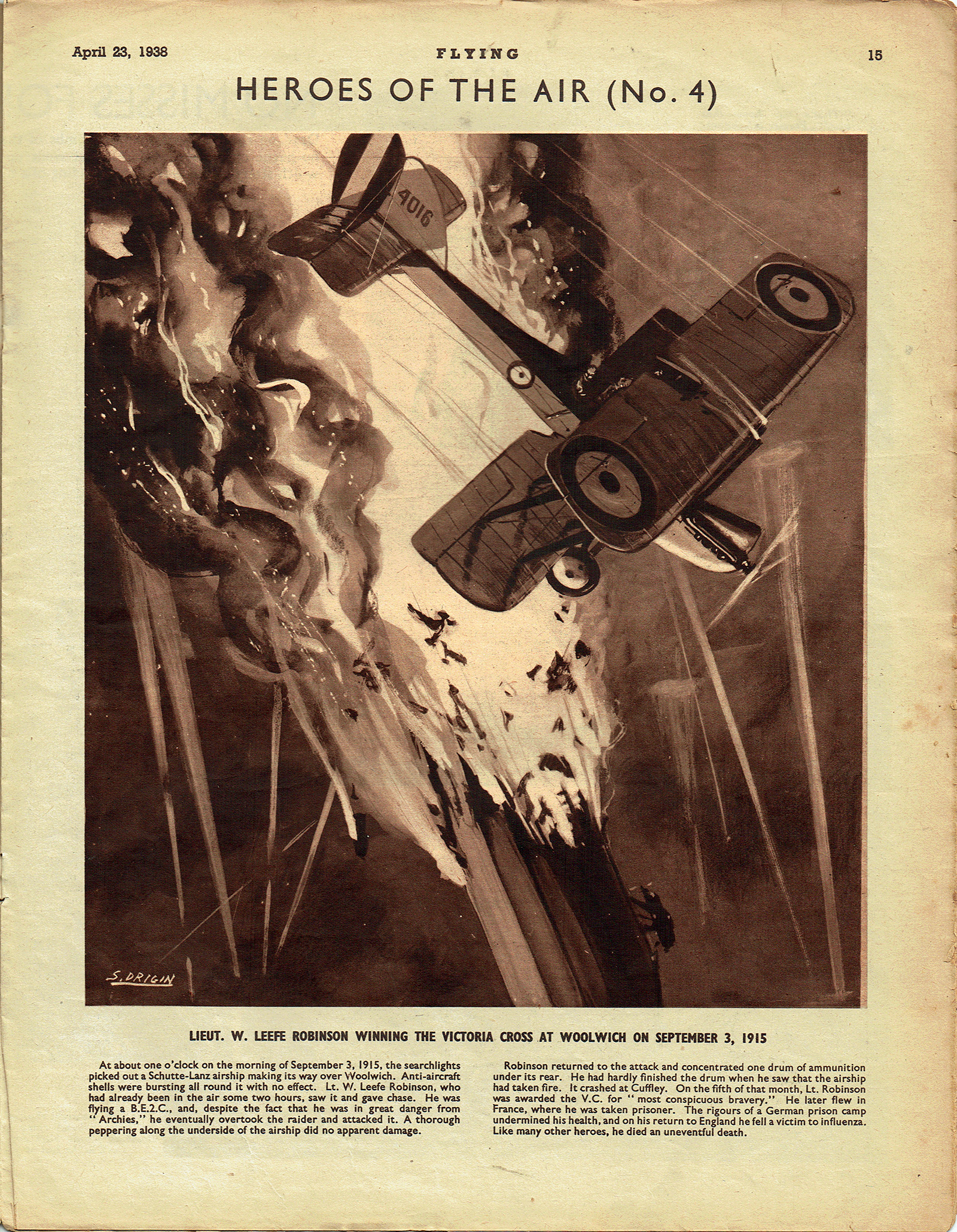

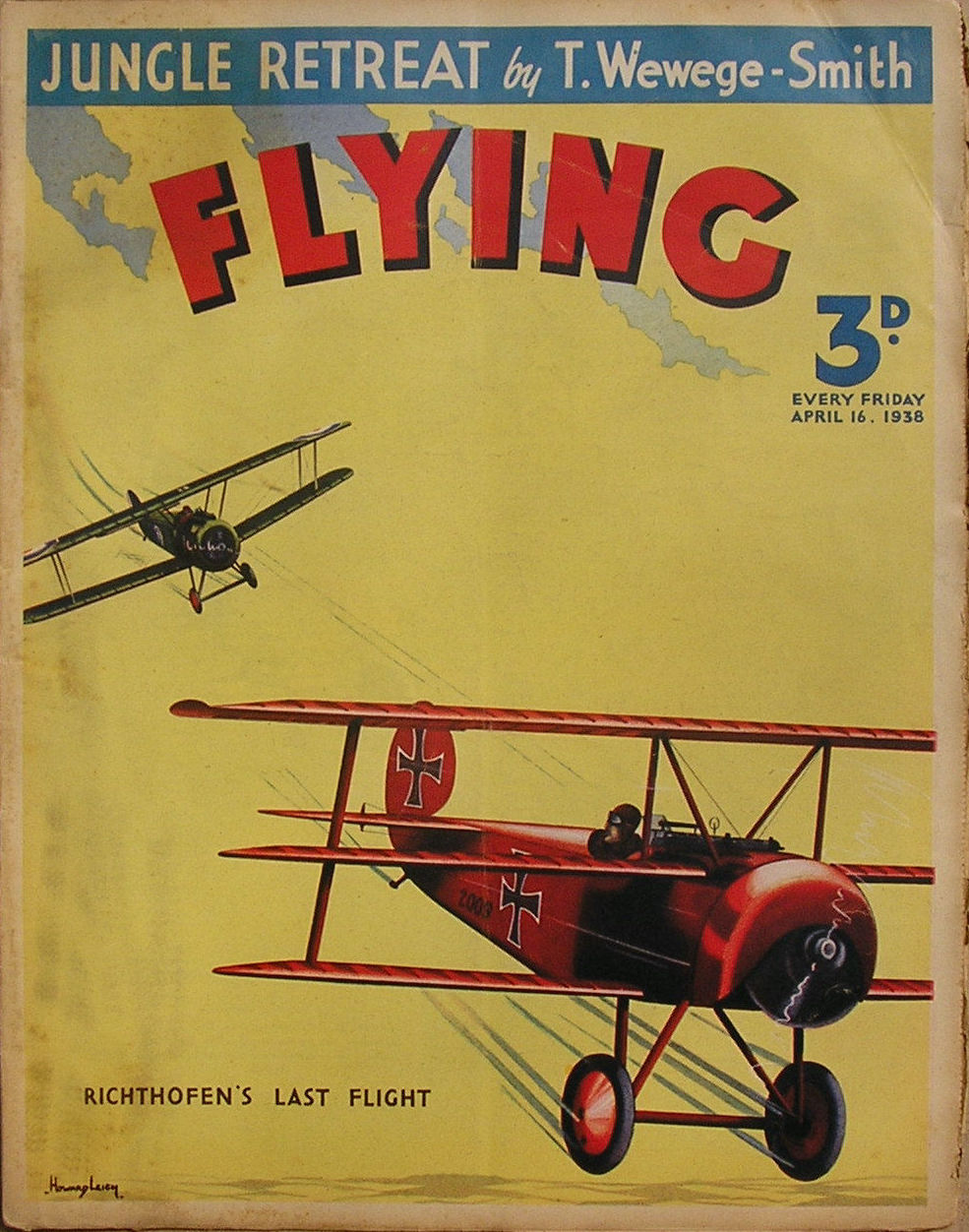

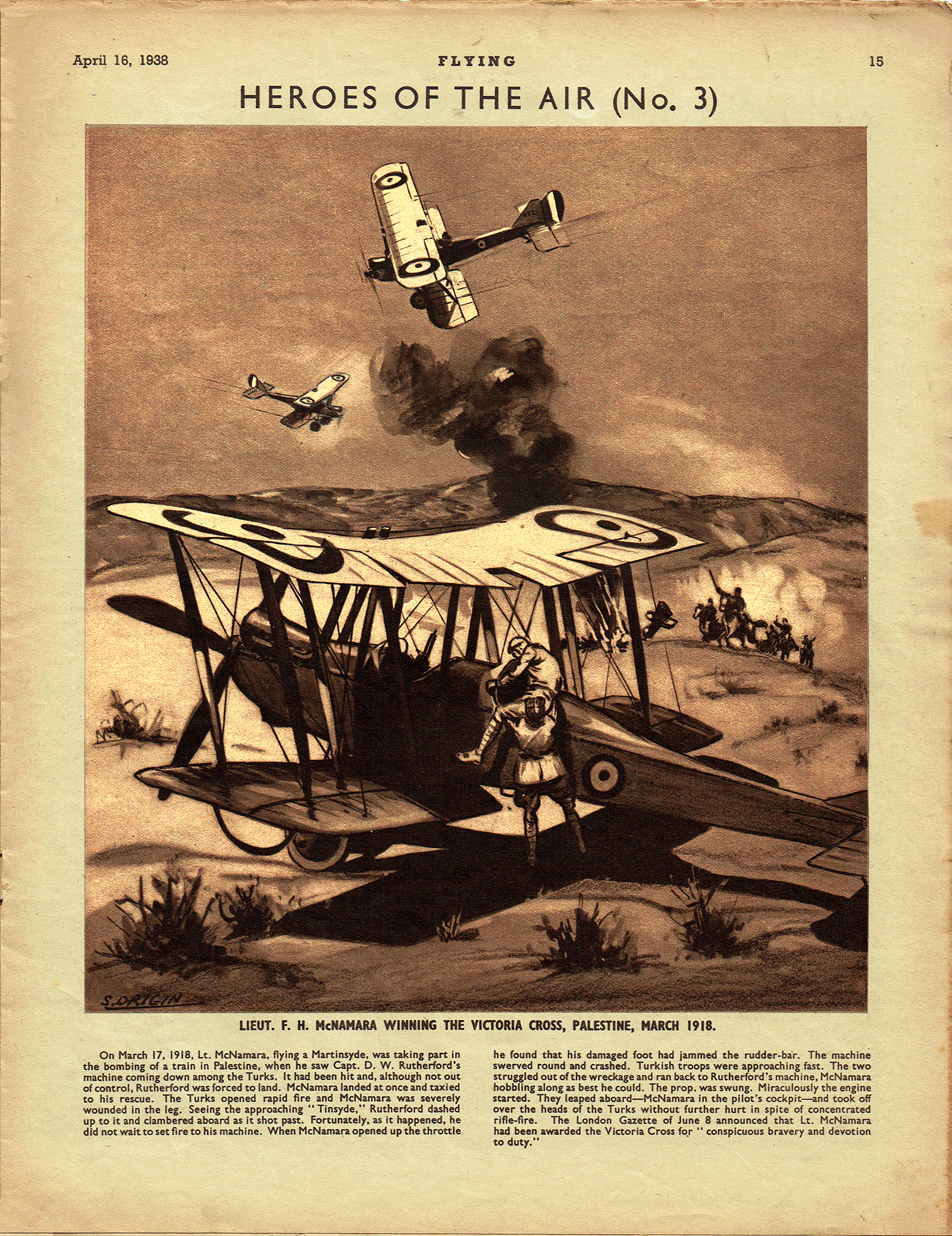

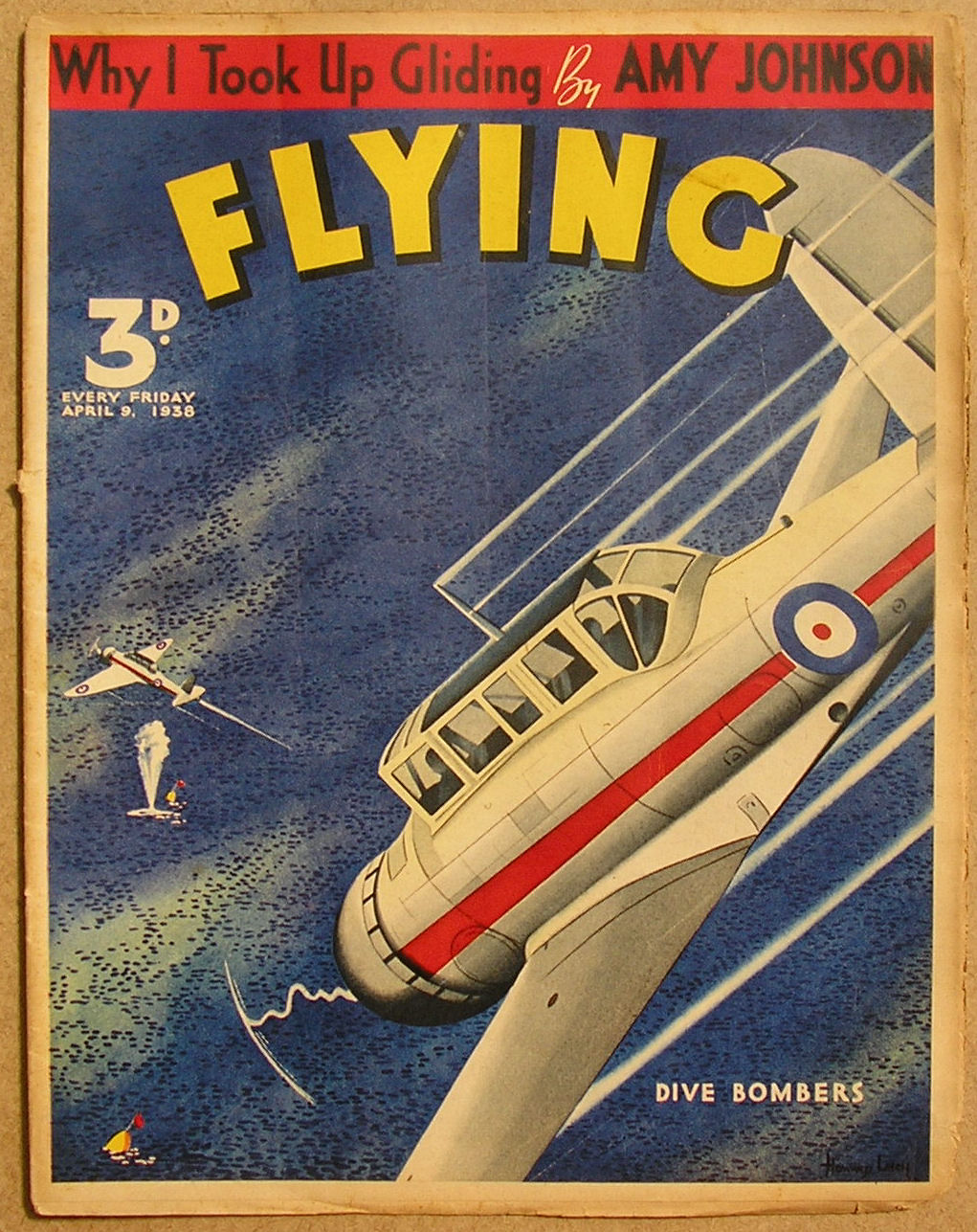

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

we have a special holiday themed tale of

we have a special holiday themed tale of  of the recently found Post War Pinkham stories that ran in the first few issues of Flying Models Magazine. It’s 2o years since the great guerre and Phineas is now running his own “Flying Carpet Airlines” whose motto is: “We Fly Anything, Anybody, Anywhere! The Sky Is The Limit!” He’s settled down in his old Boonetown, Iowa (not with Babbette) and has a son Elmer who is chief pilot at his airlines. His mechanic from the Ninth Pursuits, Casey, is chief grease monkey of the outfit.

of the recently found Post War Pinkham stories that ran in the first few issues of Flying Models Magazine. It’s 2o years since the great guerre and Phineas is now running his own “Flying Carpet Airlines” whose motto is: “We Fly Anything, Anybody, Anywhere! The Sky Is The Limit!” He’s settled down in his old Boonetown, Iowa (not with Babbette) and has a son Elmer who is chief pilot at his airlines. His mechanic from the Ninth Pursuits, Casey, is chief grease monkey of the outfit. weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

of the recently found Post War Pinkham stories that ran in the first few issues of Flying Models Magazine. It’s 2o years since the great guerre and Phineas is now running his own “Flying Carpet Airlines” whose motto is: “We Fly Anything, Anybody, Anywhere! The Sky Is The Limit!” He’s settled down in his old Boonetown, Iowa (not with Babbette) and has a son Elmer who is chief pilot at his airlines. His mechanic from the Ninth Pursuits, Casey, is chief grease monkey of the outfit.

of the recently found Post War Pinkham stories that ran in the first few issues of Flying Models Magazine. It’s 2o years since the great guerre and Phineas is now running his own “Flying Carpet Airlines” whose motto is: “We Fly Anything, Anybody, Anywhere! The Sky Is The Limit!” He’s settled down in his old Boonetown, Iowa (not with Babbette) and has a son Elmer who is chief pilot at his airlines. His mechanic from the Ninth Pursuits, Casey, is chief grease monkey of the outfit. magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

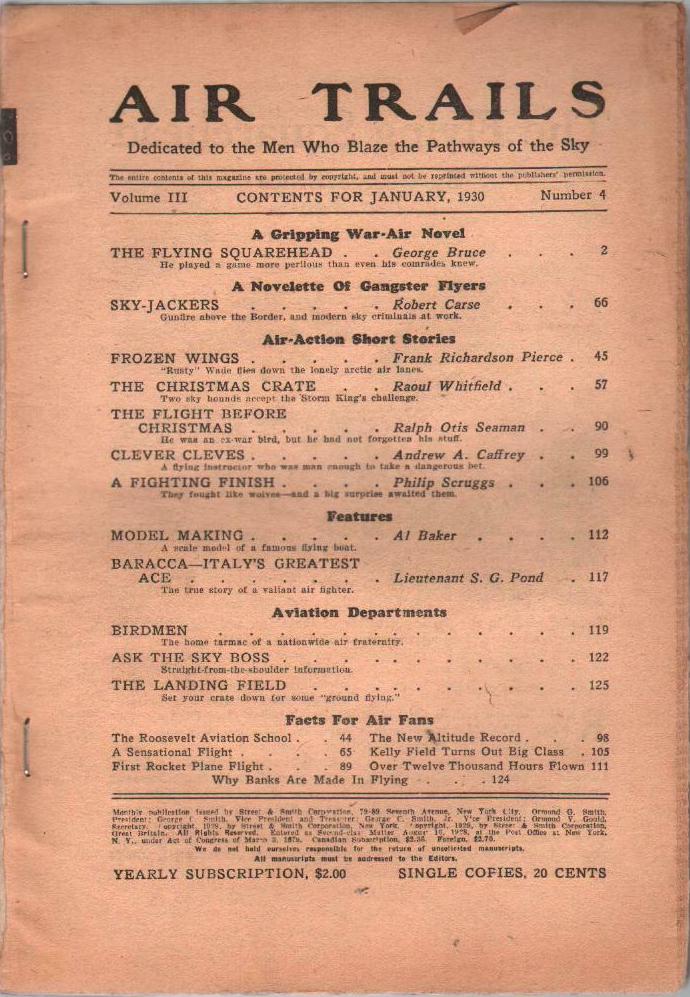

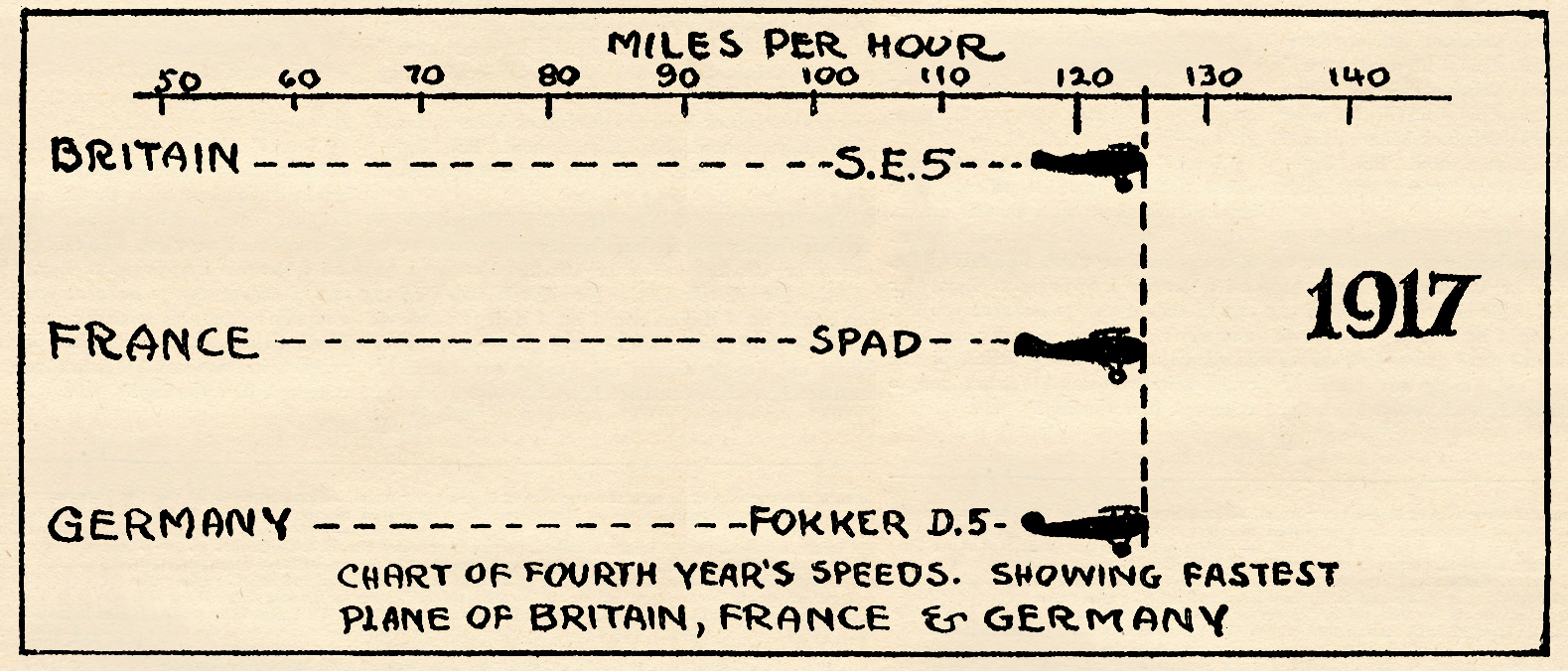

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

we’ll be posting the three post war Pinkham stories from Flying Models Magazine. In this first story, Flying Carpet Airlines is engaged to transport a pair of corpses to Cleveland. Phineas hopes to get double duty out of the flight and hop a ride to Cleveland where he’s been invited by his old hutmate Bump Gillis to entertain at his Rotarian meeting, but runs into a little trouble with some spies on the way! From the June 1947 premiere issue of Flying Models, “Phineas Pinkham Flies Again!”

we’ll be posting the three post war Pinkham stories from Flying Models Magazine. In this first story, Flying Carpet Airlines is engaged to transport a pair of corpses to Cleveland. Phineas hopes to get double duty out of the flight and hop a ride to Cleveland where he’s been invited by his old hutmate Bump Gillis to entertain at his Rotarian meeting, but runs into a little trouble with some spies on the way! From the June 1947 premiere issue of Flying Models, “Phineas Pinkham Flies Again!”

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!  a story by another of our favorite authors—

a story by another of our favorite authors— magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!