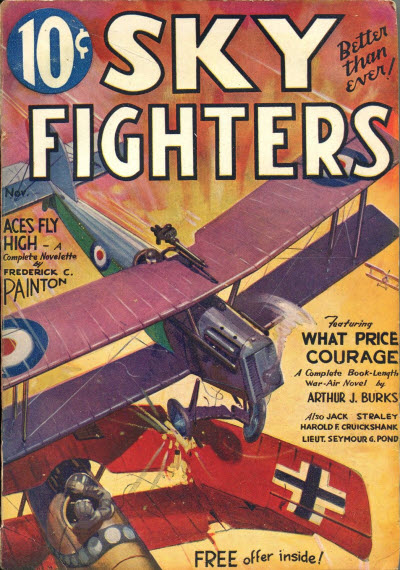

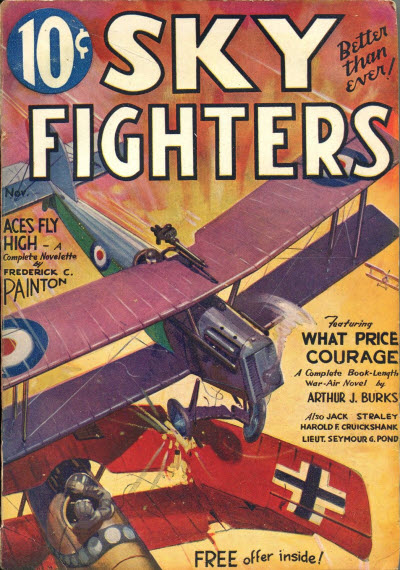

FROM the pages of the November 1933 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

Things to Inspect

by Robert Sidney Bowen (Sky Fighters, November 1933)

A WHILE back I told you buzzards a few things about knocking engines. In other words, some reasons why the engines of the old war crates used to pass out oil us now and then, and sort of leave us in the soup. Well, today I’m going to talk about things that could happen to the plane, and likewise put us in the soup.

I believe I’ve only mentioned this fact about seven million times, so I’ll just say it again—taking good care of your ship was about fifty percent of the war pilot’s job. Now, when I say, taking good care of your ship, I don’t mean being easy with it when you’re in a dog scrap. At a time like that it’s a case of your life or the other chaps, and naturally you have to take a lot of chances that you wouldn’t take if you were just buzzing around on a little joy hop. And when I speak of taking a lot of chances I mean forcing your ship to execute maneuvers that it may not be able to stand—and as a result, tear itself apart in mid-air.

Good Pilots Don’t Take Chances

But here’s the point—good pilots didn’t take chances with their ships! And why? Well, buzzards, for this reason. A good war pilot knew his ship from prop boss to tail skid. He knew from experience in the cockpil just what it would do, and just what it wouldn’t do. And how come he knew all that? For the simple reason that he cared for it as a mother would care for a new-born babe. And naturally enough! Gosh almighty, a war pilot’s ship was the difference between life and death for him.

But enough of that stuff. What we are chinning about right now, is what used to happen to war crates, and why it did happen.

Three Important Parts

GENERALLY speaking, there are three parts of an airplane that can fail and as a result cause a lot of trouble, to say nothing of causing the death of the pilot. And those three parts are, the wing fittings, the landing gear (undercarriage) and the controls. As I said in the beginning, we’ve already talked about the engine, so we’ll leave that very important part out of this meeting.

Okay, first the wing fittings.

In a biplane (and all pursuit ships at the end of the war were biplanes) there were at least four, and in many cases eight, wing fittings, or wing bolts as they were sometimes called. And if you want to count in the aileron bolts, that’s eight more.

Now just a minute, don’t get so doggone impatient. I know what you are going to ask. Just what is a wing fitting, eh? Well, a wing fitting, or wing bolt, or wing attachment bolt (all the same thing) is simply the bolt hinge by which a wing is fastened to something else.

Take the top span of a biplane, for example. It is made up of three parts. They are, the left top wing, the center section, and the right top wing. Now, the center section is solid.

BY THAT I mean it is attached to the fuselage by struts and cross bracing wires. But the left and right top wings are hinge bolted to it on their respective sides (Fig. 1). The inner end of the wing is a solid rib. (Not holed out for lightness like the rest of the ribs in the wing.) Into that solid rib is fitted the forward and rear spars of the wing. The same thing is true of the spars in the center section. So that makes re-enforced solid pieces coming together. In other words, something strong against which you can fasten the hinge fittings.

Hinge Fittings Varied

Now the hinge fittings varied in different types of ships. But the one used quite a lot was like the one in Fig. 2. As you can see, the two parts of the hinge simply slide together and the bolt is slipped through the holes and held in place by a cotter pin at the rear end of the bolt.

With reference to the lower wings, the idea of attachment is exactly the same. Except, of course, you fasten the left and right lower wings to the left and right lower longerons of the fuselage. In some planes, though, the left and right lower wings were all one piece. That is, the spars extended right through the fuselage, and the whole thing could be fastened solidly to the fuselage.

If the wings are hinged, why don’t they fall down? Because of the wing struts and wing cross bracing wires.

No Danger of Sagging

AERODYNAMICALLY speaking, the top and lower wings of a biplane are a solid piece in themselves. When the struts are put in, and the wings are tightened up there is no sagging strain on the wing attachments. So although they may only be fastened to the body of the ship, and to the center section, by small bolts, there is no danger of them sagging in flight or on the ground and pulling the wing fastenings loose.

No, not if the pilot of that ship knows his onions and has a good rigger (name given to the mechanic that is responsible for the rigging of the ship). However, if the pilot is slipshod, and the rigger doesn’t give a darn, a lot of things can happen. To begin with, the wing fastening bolts should be put in from front to rear, and the cotterpin should be in place. If not, then engine vibration is apt to shake the bolt out, and if it does—wham, your wing tears itself off.

Another thing, the cross bracing wires between the wings should be neither too loose nor too tight. If they are too tight, extra strain cahsed by violent maneuvering in a dog scrap might make them part. And if enough of them do that, your wings will just naturally fold up on you, and you’ll get no more of mother’s cooking.

The Turnbuckle

AS YOU probably know, the cross bracing wires are adjusted by turnbuckles. And a turnbuckle is simply a rod, tapered at both ends, a hole through it in the middle (to enable twisting), and a threaded hole at each end.

For the idea look at Fig. 3. The turnbuckles are fastened by wire at one end to the strut stubbs and the other end is fastened to the wire that is to do the bracing. Naturally, excess strain, vibration, etc., can make turnbuckles untwist a bit. And the result is a slack bracing wire.

And so, with reference to the wings there are several things that the good pilot takes care of and inspects every time he lands after a scrap. And lots of other times, too. He makes sure the bolts are in right. He makes sure that the locking cotter pins are in the bolts. He makes sure that the turnbuckles have not untwisted. And last but not least he makes sure that all those parts have enough grease on them and have not become rusted (and thus weakened) by exposure.

If he doesn’t do those things, he will be flying a weakened ship, that looks strong enough on the surface, but which will fold up on him some day.

The second part of the ship that needs constant watching is the landing gear or undercarriage.

What “Split Axle’’ Means

THE ships of today have what are known as split axle landing gears, and most all of them are equipped with Aero shock absorbers. By split axle we mean just that—the axle is in two parts, hinged in the middle, with the middle part higher than the two ends, so that the axle can spread outward due to the weight of the ship above it.

But, the war crates had solid axles with a wheel at each end. The axle went through vertical slots in the landing gear struts, and was held in place at the lower end of the slot by rubber cords. Thus when a ship landed the axle would try to travel up the slot in the landing gear struts, but the rubber cord would tend to hold it back. And the result was that most of the shock in landing was absorbed by the wound rubber cording stretching. Perhaps you’ll get a better idea of what I’m talking about by glancing at Fig. 4.

Of course, the wheel was fastened to the axle by a nut with locking cotterpin. The axle was stationary and the wheel revolver about it.

Now, a bad landing could weaken the rubber cording. A bum pilot might leave the locking cotter pin out of the nut on the end of the axle. A bum pilot might forget to change the rubber cording when it got too old for good use. And a bum pilot might weaken his landing gear cross bracing wires and not trouble about it.

Here’s What Could Happen

AND if he did, here’s what could and probably would happen. He might lose a wheel when taking off from bumpy ground.

His whole undercarriage might fold up on him sometime when he made a bad landing. A wheel might buckle when making a cross-wind landing. And if the rubber on one side gave way, the ship would be flung over that way when he landed, even if it was a good landing. And the result of any one of those things happening would be a nasty ground loop, if not a direct crash.

And just to show how dumb even yours truly can be, I’ll admit that once I lost a wheel while taking a Spad off. What happened? Well, a Spad always lands like two tons of brick, even with two wheels on—and with one gone, well, I plowed up enough of that drome to plant a year’s supply of potatoes, and it was a couple of weeks before all the skin grew back on my face.

And now for the third, and yes, the most important part to keep your eye on. Naturally, I mean the controls.

You can have a bum engine, you can have a badly rigged ship, and you can have a weakened undercarriage, yet somehow you can manage to get down, and probably walk away from the wreck. But—and that’s a big but—if your controls go cockeyed, you might just as well buy yourself a oneway ticket to the Pearly Gates. Or at least become resigned to a long stay in a little white cot in some hospital.

As I told you sometime ago, the controls of an airplane consist of the rudder bar and the joystick. The rudder bar works the rudder, and the joystick works the elevators and the ailerons. Naturally, they work them by the means of wires. To the right side of the rudder is a wire that leads back to the horn on the right side of the rudder. The same thing on the left side. Now, from the joystick four wires lead back to the elevators. Two for the top and bottom of the right elevator, and two for the top and bottom of the left elevator. Also from the joystick, wires lead out to the ailerons.

Now, just how many control wires were used, and how they were lead out to the various control surfaces, depended upon the type of machine. But, on any type of ship, turnbuckles were used for tightening or slackening, pulleys were used where the wire had to go around a bend, and leather guides were used wherever the wire unavoidably rubbed against something.

Wires Constantly Moved

Naturally it follows that the wires were constantly being moved while in flight. That means that some of them were constantly sliding around on pulleys, and others were constantly rubbing against leather guides.

Contact means friction, and friction means wear. Added to that was the strain of violent maneuvering, the full force of which was instantly transmitted to the turnbuckles and the wire eyes. (See Fig. 3.)

Now if the pilot did not take constant care of his controls he was simply flirting with his life. For example, take the pulleys. (Fig. 5.) Dirt, grease and other things such as dope flakes, could very easily jam them so that they would not turn. As a result the wire would slide around it, instead of the pulley revolving with the wire. Naturally the wire couldn’t stand that very long—and suddenly it would give way, and the pilot would be helpless to use his ailerons.

In other words, lateral stability would be all lost. In most planes the pulleys were inside the wing, and you got at them by unlacing a bit of the fabric. Doing that little thing was tiresome, but lordy how important!

The leather guides wore out very quickly and if they were not replaced with new guides you might find that your control wire was rubbing against a fuselage cross-bracing wire. And you can figure out for yourself what happens when steel cable rubs against steel cable. An example of where and how leather guides were used will be noted in Fig. 6.

And as for the turnbuckles and wire eyes. Well, the same points hold true for them as for cross-bracing wire turnbuckles. Get the wires too tight and a savage loop might part them. Let them get rusty and the eyes might pull out of the turnbuckles, or the turnbuckle itself give way. And so you make sure that there is plenty of grease on them to insure no rust.

AND that, incidentally, goes for the control wires themselves. They should always have a light coating of grease to prevent rust. And for a thorough inspection, the good pilot always runs his fingers along the wires, to see if they have become weakened by a strand or two parting. And when your finger suddenly gets a pin prick, stop, look and be a bright boy. Take out the whole wire and replace it with a new one. One strand breaking does not mean death is coming to you. It simply means that the wire has been weakened just that much—and maybe the other strands will let go when you’re ten thousand feet up.

Pay Attention, Buzzards!

Well, you’re all asleep now, so I guess I’ll go home. But remember this (if it’s possible) your engine is important, but so is the ship itself. It may seem like a waste of time to crawl all over it with an eagle eye each time before you go up. But listen to me, buzzards, I’ve seen plenty who figured it a waste of time, and took a chance. Well, they lost. I’m a scare-cat—I hate to take chances—maybe that’s why I’m still able to admire the trees and the flowers and other things in life on this man’s planet!

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author James Perley Hughes! Hughes was managing editor of the San Francisco Chronicle before turning his hand towards fiction and becoming a frequent contributor to various adventure pulps—but he seemed to gravitate toward the air-war spy type stories.

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author James Perley Hughes! Hughes was managing editor of the San Francisco Chronicle before turning his hand towards fiction and becoming a frequent contributor to various adventure pulps—but he seemed to gravitate toward the air-war spy type stories.

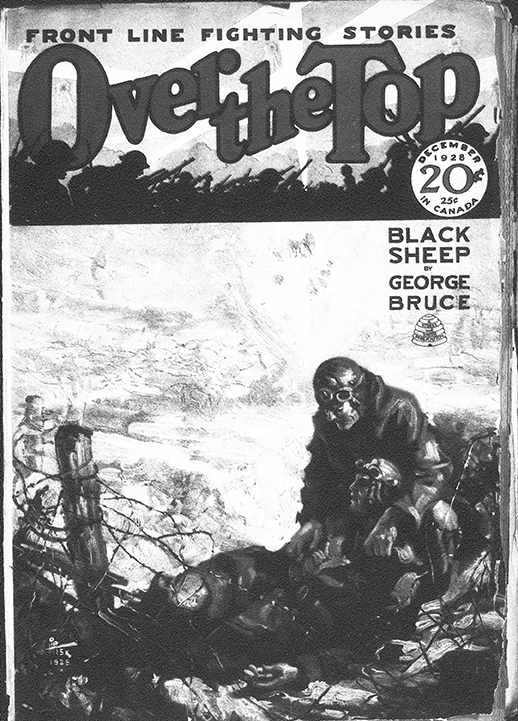

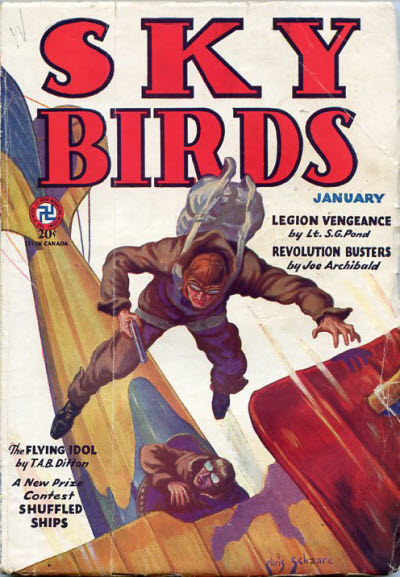

another Buck Manley story by Lloyd Leonard Howard from the pages of Street & Smith’s short lived Over The Top magazine. Over The Top was a magazine featuring war stories by the likes of Arthur Guy Empey, George Bruce, Raoul Whitfield among others. One of those others being Lloyd Leonard Howard who had stories in about a dozen of the 21 issues. Several of them featured a pilot by the name of Lieutenant Buck Manley and his pal Lieutenant “Stubby†Davis. For some reason or other, enemy craft were scarce since the St. Mihiel drive and although Boche crates were few and far between there were still Boche observation Balloons to down! From the December 1928 issue of Over The Top, it’s Lloyd Leonard Howard’s “Buck Manley, Balloon Buster!”

another Buck Manley story by Lloyd Leonard Howard from the pages of Street & Smith’s short lived Over The Top magazine. Over The Top was a magazine featuring war stories by the likes of Arthur Guy Empey, George Bruce, Raoul Whitfield among others. One of those others being Lloyd Leonard Howard who had stories in about a dozen of the 21 issues. Several of them featured a pilot by the name of Lieutenant Buck Manley and his pal Lieutenant “Stubby†Davis. For some reason or other, enemy craft were scarce since the St. Mihiel drive and although Boche crates were few and far between there were still Boche observation Balloons to down! From the December 1928 issue of Over The Top, it’s Lloyd Leonard Howard’s “Buck Manley, Balloon Buster!”

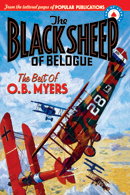

the prolific O.B. Myer’s! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the

the prolific O.B. Myer’s! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the  O.B. Myer’s didn’t really have any series characters. The few recurring characters he did have in the pages of Dare-Devil Aces, we’ve collected into a book we like to call “The Black Sheep of Belogue: The Best of O.B. Myers” which collects the two Dynamite Pike and his band of outlaw Aces stories and the handful of Clipper Stark vs the Mongol Ace tales. If you enjoyed this story, you’ll love these stories!

O.B. Myer’s didn’t really have any series characters. The few recurring characters he did have in the pages of Dare-Devil Aces, we’ve collected into a book we like to call “The Black Sheep of Belogue: The Best of O.B. Myers” which collects the two Dynamite Pike and his band of outlaw Aces stories and the handful of Clipper Stark vs the Mongol Ace tales. If you enjoyed this story, you’ll love these stories!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

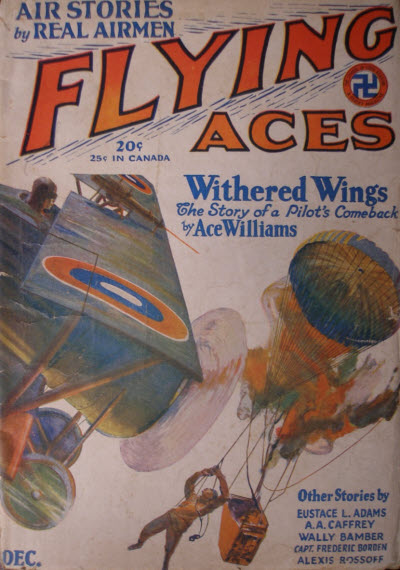

a story from a author new to Age of Aces—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the late 1920’s through 1950. In “Flying Odds,” Caffrey gives us a taut tale of Lieutenant Wood trying to get as far back to allied territory as possible when the engine of his Spad conks out.

a story from a author new to Age of Aces—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the late 1920’s through 1950. In “Flying Odds,” Caffrey gives us a taut tale of Lieutenant Wood trying to get as far back to allied territory as possible when the engine of his Spad conks out. magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

a story from the pen of British Ace,

a story from the pen of British Ace,  weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

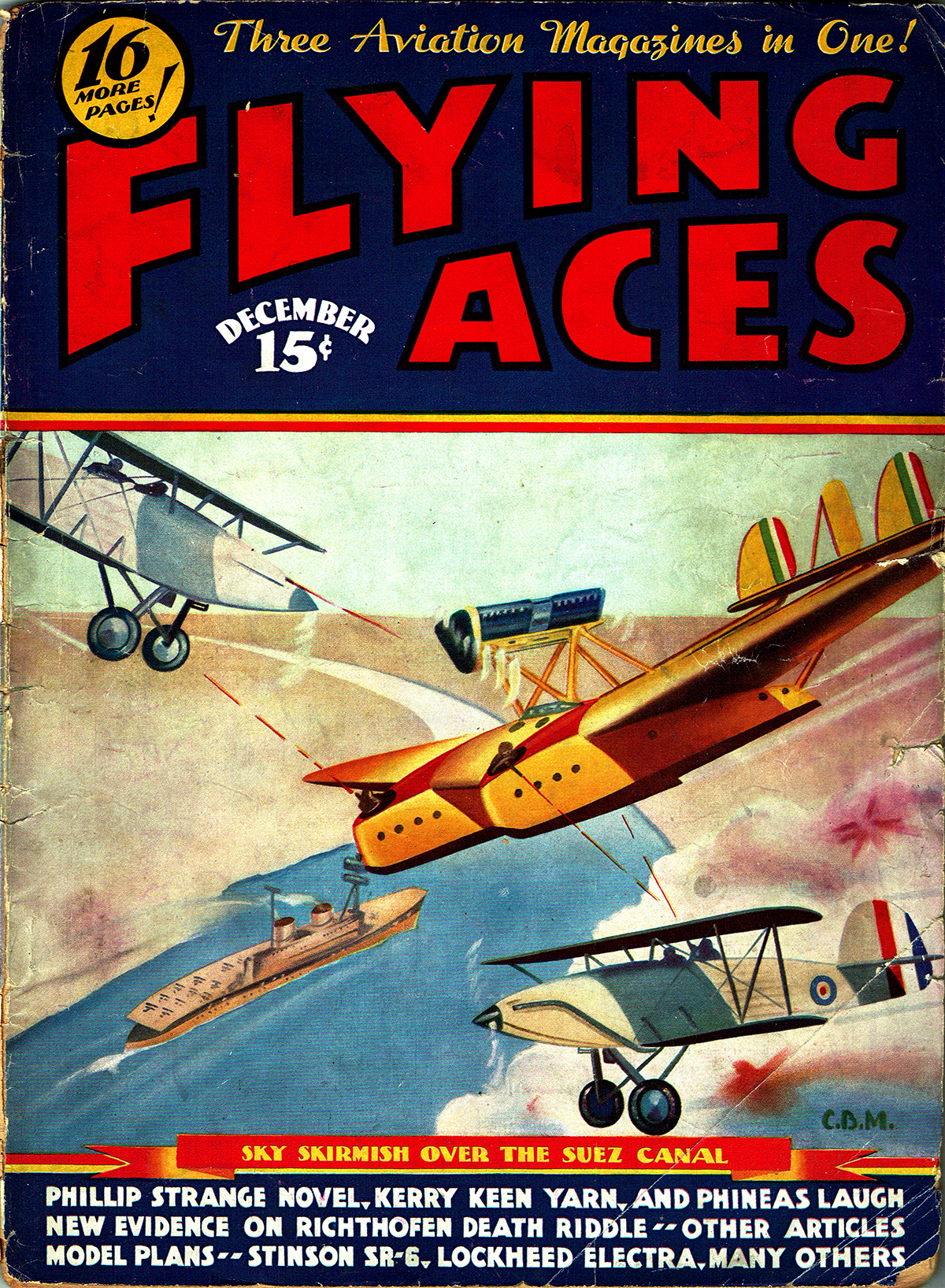

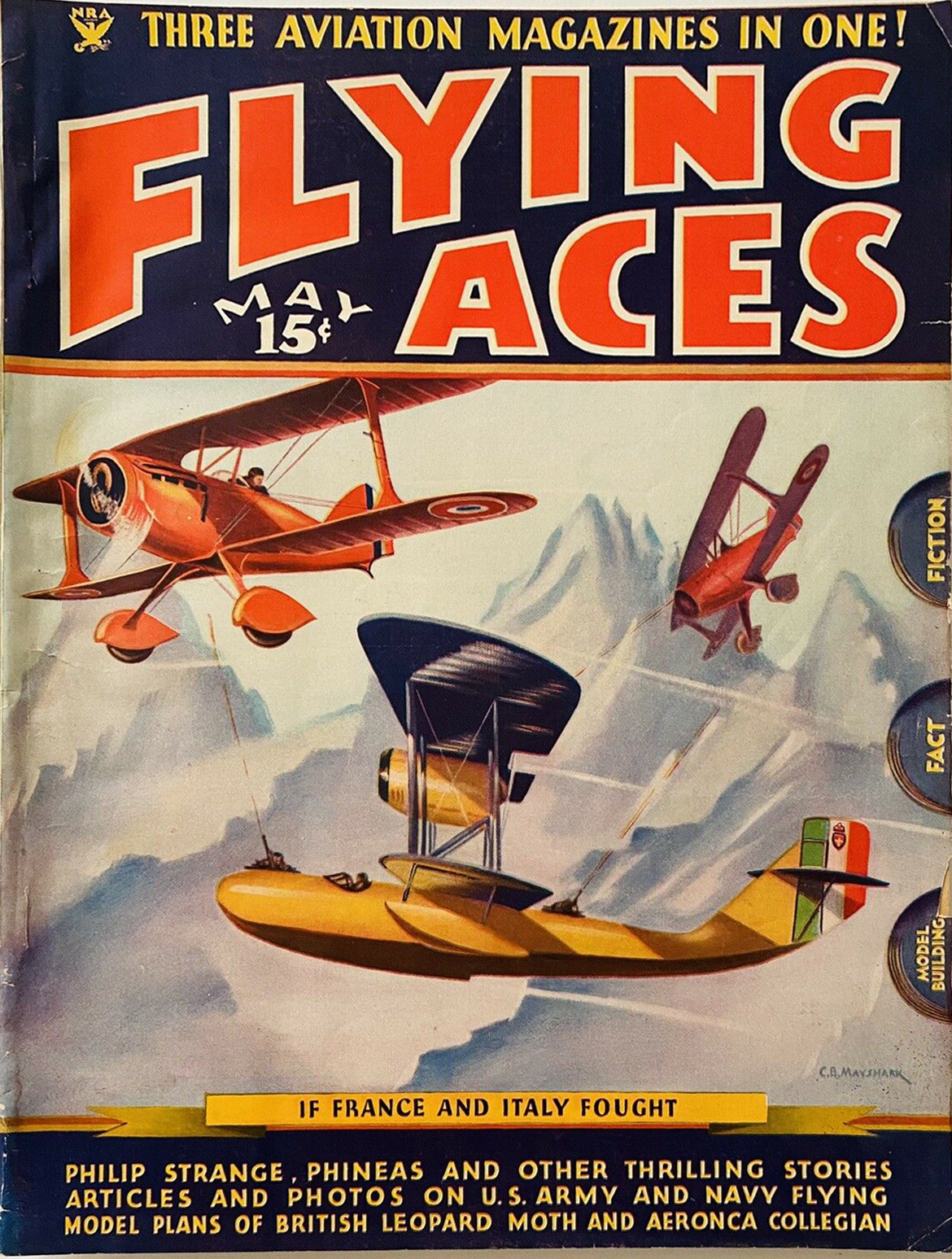

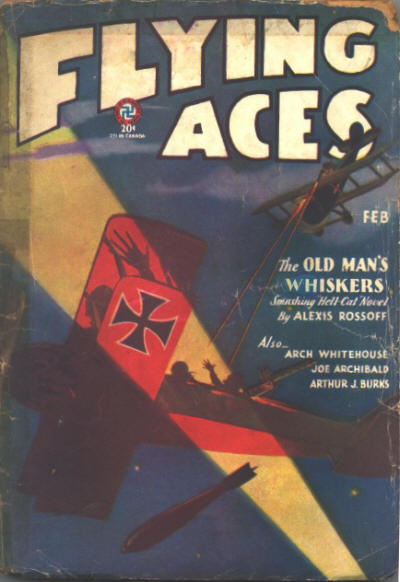

tale of the Hell-Cat Squadron from the prolific pen of Alexis Rossoff. The adventures of the Hell-Cat Brood ran in War Birds, War Stories and Flying Aces. The Seventy-Seventh Squadron had a reputation of being short on technique and long on defying every regulation in the book. The squadron was the cause of many gray hairs on the pates of the star-spangled ones back in G.H.Q. They flew their merry way like nobody’s business, and played hell with any Jerry who tried to dispute their intention of going places. This bunch of cloud-hopping war birds were known from one end of the Western front to the other as the “Hell-cats”—and sometimes the “Unholy Dozen!”

tale of the Hell-Cat Squadron from the prolific pen of Alexis Rossoff. The adventures of the Hell-Cat Brood ran in War Birds, War Stories and Flying Aces. The Seventy-Seventh Squadron had a reputation of being short on technique and long on defying every regulation in the book. The squadron was the cause of many gray hairs on the pates of the star-spangled ones back in G.H.Q. They flew their merry way like nobody’s business, and played hell with any Jerry who tried to dispute their intention of going places. This bunch of cloud-hopping war birds were known from one end of the Western front to the other as the “Hell-cats”—and sometimes the “Unholy Dozen!” Mosquito Month we have a non-Mosquitoes story from the pen of Ralph Oppenheim. In the mid thirties, Oppenheim wrote a half dozen stories for Sky Fighters featuring Lt. “Streak” Davis. Davis—ace and hellion of the 25th United States Pursuit Squadron—was a fighter, and the speed with which he hurled his plane to the attack, straight and true as an arrow, had won him his soubriquet. Once more it’s a battle against time as Streak must retrieve vital information about Pershing’s big push against Hindenburg that had been left behind in a locked safe when the Boche over ran the villa that had been an Allied held town. From the April 1935 issue of Sky Fighters it’s “Death Takes Off!”

Mosquito Month we have a non-Mosquitoes story from the pen of Ralph Oppenheim. In the mid thirties, Oppenheim wrote a half dozen stories for Sky Fighters featuring Lt. “Streak” Davis. Davis—ace and hellion of the 25th United States Pursuit Squadron—was a fighter, and the speed with which he hurled his plane to the attack, straight and true as an arrow, had won him his soubriquet. Once more it’s a battle against time as Streak must retrieve vital information about Pershing’s big push against Hindenburg that had been left behind in a locked safe when the Boche over ran the villa that had been an Allied held town. From the April 1935 issue of Sky Fighters it’s “Death Takes Off!”

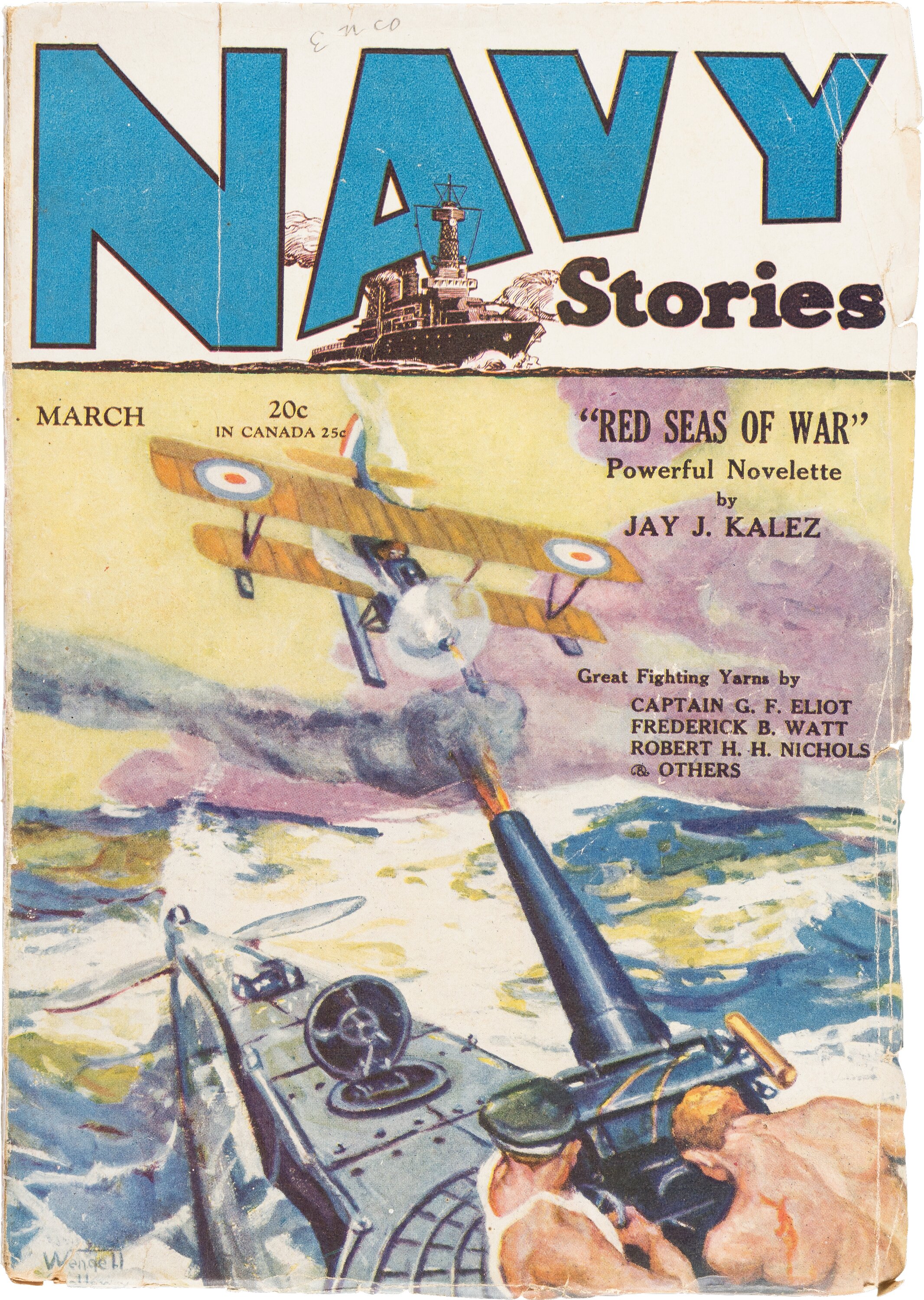

the third of three Three Mosquitoes stories we’re presenting this month. This week it’s a bit of a departure for the inseparable trio when they are loaned out to the Navy. Somehow, under our very noses in the heavily mined and patrolled waters of the English Channel, six ships have disappeared without a trace and no survivors. The Navy has designed a trap that they hope will catch or reveal what has happened to their missing ships and The Three Mosquitoes are to fly over the area to observe whatever happens. And that’s just the tip of this iceberg—events lead Kirby to be an unwilling passenger/prisoner aboard a U-boat bent on a hellish suicide mission to destroy Englands new super dreadnaught about to set sail! From the March 1929 issue of Navy Stories, it’s “Aces of the Sea!”

the third of three Three Mosquitoes stories we’re presenting this month. This week it’s a bit of a departure for the inseparable trio when they are loaned out to the Navy. Somehow, under our very noses in the heavily mined and patrolled waters of the English Channel, six ships have disappeared without a trace and no survivors. The Navy has designed a trap that they hope will catch or reveal what has happened to their missing ships and The Three Mosquitoes are to fly over the area to observe whatever happens. And that’s just the tip of this iceberg—events lead Kirby to be an unwilling passenger/prisoner aboard a U-boat bent on a hellish suicide mission to destroy Englands new super dreadnaught about to set sail! From the March 1929 issue of Navy Stories, it’s “Aces of the Sea!”