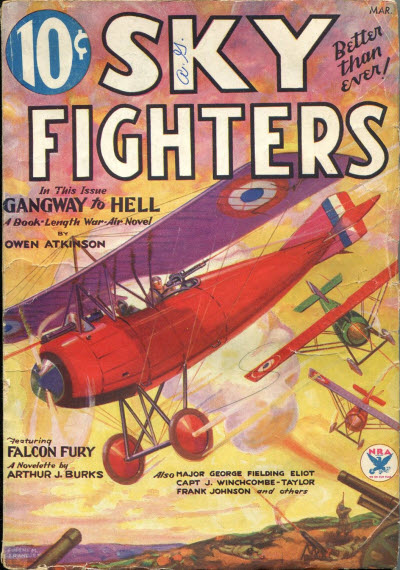

FROM the pages of the February 1934 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

Guns and Howitzers

by Robert Sidney Bowen (Sky Fighters, February 1934)

BY THIS time, you yeggs—excuse me, my error. I’ll start all over again. By this time, you buzzards must be convinced that we war pilots were very wonderful fellows.

Of course, being a modest old sparrow I can do nothing else but agree with you. However, to be serious for a few moments, the object of this little get-together is to point out that the pilot who was sent to the Front during the last war had to know quite a bit about war activities other than just the flying end.

When you enlisted there was really no way of determining whether you would be okay on pursuit ships, observation ships, or bombers. That being the case, the training you received was more general than specialized.

By that I mean, you were taught at ground school the various duties of all three types of pilots. And upon your flying depended what kind of a squadron you’d be sent to—if any!

For instance, it might so happen that once you had been sent solo you proved yourself to be a knockout on artillery co-operation work. In that case you’d be shipped to an observation squadron. And then again, perhaps, you might be a dead shot. In that case, out you’d go to a pursuit unit.

Get the Idea?

Why waste a swell shot by sticking him at the controls of a bomber? Get the idea?

Naturally, war being just as mixed up as anything else, the right men were not sent to the right squadrons all the time. There were plenty of misfits floating around—birds pushing bombers around when they should be at the controls of a pursuit or an observation ship, and vice versa. However, that sort of stuff was not the fault of the pilot in question.

Just One of Those Things

It was just one of the many, many things that can happen in war. In other words, you were sent where the big shots sent you, and that was that. You couldn’t do anything about it, except weep in your own soup.

I remember a case in particular. There were two friends of mine, one a big bruiser and the other a little half pint portion of man—but plenty scrappy, nevertheless. Well, we all trained together, and when it came time for us to be assigned to squadrons, the big fellow was sent out to a Camel squadron and the little fellow was shipped out to fly Handley-Page bombers.

The funny part of it was that I met them both about six months later, and the big fellow had to have his Camel cockpit made bigger so he could get into it, and the little fellow had to pile leather cushions in his Handley-Page cockpit in order to see over the top of the cowling.

They both came through the war with flying colors, so maybe the big shots guessed right after all.

However, whether they did or not, isn’t any skin off our noses today. What I’m trying to get over to you chipmunks is, that while you were training for the Front you were learning lots of things about war besides flying. In other words, you had to be able to fill any gap at a moment’s notice.

And so, I’m going to yell about one of the extra items we had to get through our heads before they let us go. And that item is ordnance.

Or—what? You heard me, ordnance! And being as how you don’t know what that means, I suppose I’ll have to tell you. The correct definition of ordnance is, the general name for all kinds of weapons and their appliances used in war; especially, artillery.

What’s a Gun—Huh?

That last is what I’m going to talk about—artillery.

There were, generally speaking, three types of artillery used. The first was guns, the second was howitzers, and the third was mortars.

Now wait a minute, keep your shirt on and stop asking questions so soon. I know what’s on your mind. What do I mean by guns? Well, just listen.

A gun was a piece of ordnance, cannon or pieces of artillery that was used foe, long-range fire, or in other words, line fire. A howitzer was a piece of ordnance, cannon or pieces of artillery used for short range destructive fire. And a mortar was a piece of ordnance, cannon or artillery that was used for short range, very high angle of fire bombardment work.

The Long and the Short of It

Now, let’s go into detail one at a time. First, the gun.

Of course, there were various sizes of guns. The smallest being the eighteen-pounder and the largest being the twelve-inch gun. And even bigger than that if you want to count the navel guns they sometimes mounted on mobile platforms. However, regardless of the size of the gun, the bores were all rifled to give the desired twist to the shell as it left the muzzle, so that it would travel through the air the right way.

Naturally, the driving band that circled the shell made it possible for the rifling of the bore of the gun to give a twist to the shell.

As I said, guns were used for long range work or line fire. By line fire I mean just that—the shells exploding in a line area that extended from a point on the near side of the target to a point on the far side of the target. In other words, an oblong target area. To get an exact idea of what I mean, take a squint at Fig. 1.

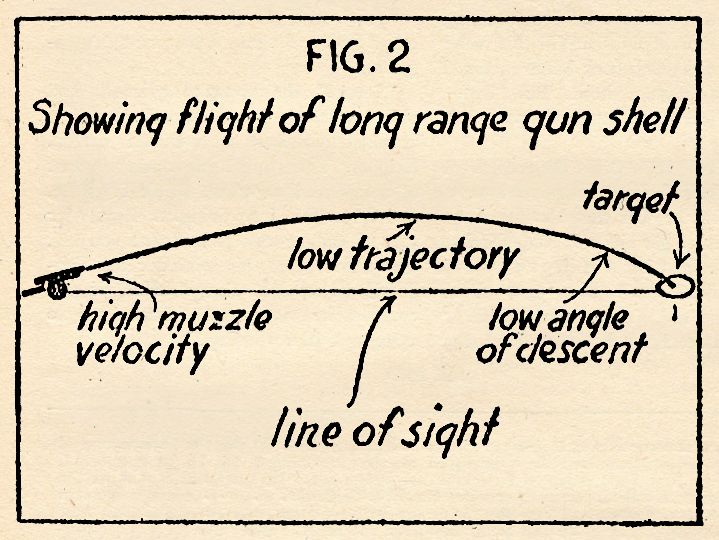

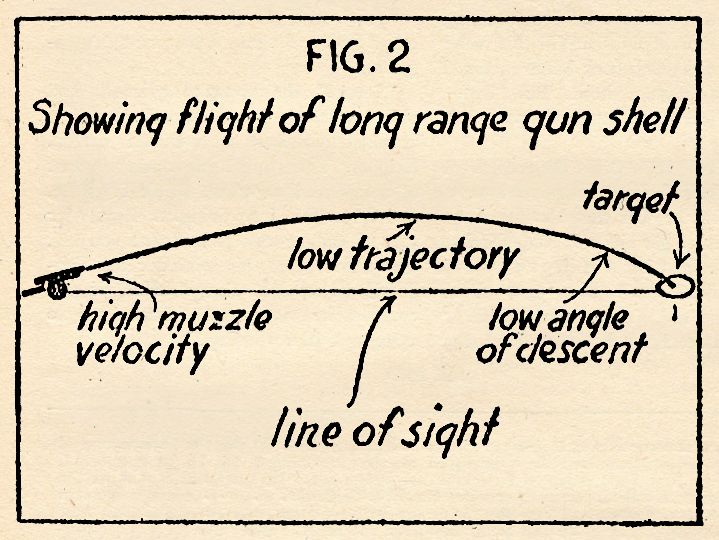

As the shell of a gun has to travel a long way, it follows that the muzzle velocity (speed of shell as it leaves muzzle of gun) is very high. However, on the other hand, the trajectory and angle of descent are very low. To explain them there big words: trajectory means angle of flight. And angle of descent, of course, means the angle in relation to the ground at which the shell descends.

Effective Range Fire

Guns were more effective on infantry movements. By that I mean, infantry columns moving along roads, field batteries moving into position, trains, railroad stations, ammo dumps, etc. In other words, targets that were either moving or stationary, but were quite a ways behind the enemy lines. See Fig. 2.

Now, I’ll get on with howitzers and you’ll be able to see just what I mean about the effective range fire of guns.

Howitzers ranged in size from four and a half inches to around sixteen inches.

Howitzers Were Accurate!

And, by the way, when I speak of size I mean the diameter of the bore of the gun or howitzer, such as the case may be.

Okay, let’s go! Howitzers were used for short-range destructive work. By that I mean, they were supposed to wipe the target right off the old map. Their range being shorter, they were far more accurate than guns. The main reason being that their area of fire was more square in shape than the area of gun-fire.

To get the point, rest your lamps on Fig. 3.

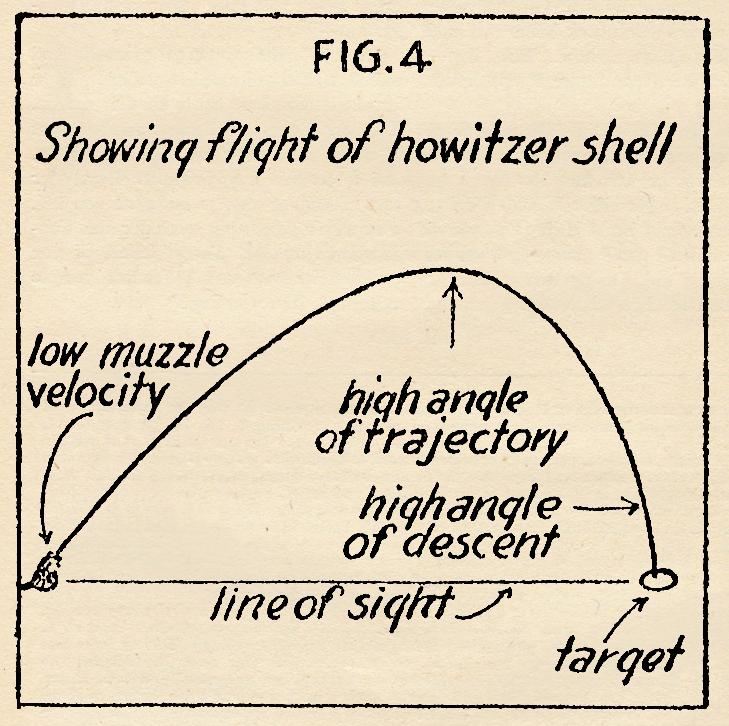

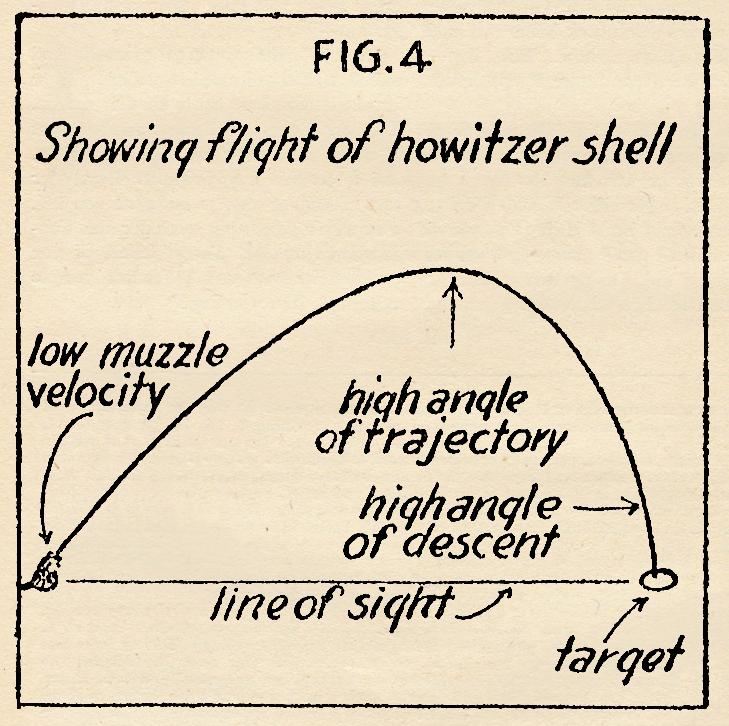

The range of howitzers being shorter the idea was to drop a shell down on it as perpendicular as possible. To do this, required low muzzle velocity, high trajectory and high angle of descent. The advantage of howitzers was that hills didn’t bother them. Their shells went up high and came down at a steep angle. So if your target was behind a hill range, you didn’t have to worry.

A gun shell that would clear the top of the hill would, of course, go beyond the target. But a howitzer shell would sneak right up over the hill and plop straight down, on the target. Take a peep at Fig. 4 and you get an idea how a howitzer shell went through the air.

Now, when I say that howitzers were for destructive work, don’t get the idea that guns didn’t destroy things. They sure did, and don’t let your cousin Alice tell you otherwise. However, perhaps you noted that howitzers pushed out bigger shells than guns, and that those shells came down straighter on the target.

Well, there you are—howitzer fire was more evenly concentrated than gun-fire, it covered a more even area about the target, and it could nail a target (within its range) regardless of ground formations. Because of its high trajectory and short range it was the bunk for moving targets.

But take an established enemy target, a field battery in position, for instance, or a troop concentration depot, and the old howitzer would give you the best results every time.

The Howitzer’s Kid Brother

A mortar was for trench to trench work. The most famous of all mortars was the Stokes trench mortar. It popped one- or two-pound shells out of your trench and down into the enemy trench. As its range of fire was nothing to write home about, a couple of hundred yards or so, the bore was not rifled, nor was there any driving band on the shell. I suppose that you could really call a trench mortar, a small edition of a howitzer without bore rifling.

Believe it or not, they were fired by dropping the shell into the muzzle. It simply slid down, detonated and came popping out again and on its way over to the enemy trench. Yes, Clarence, you had to get your hand out of the way fast. That is, of course, if you didn’t want to present the enemy with a perfectly good hand. Personally, I never met a soldier yet who didn’t want to hang onto his hands.

And there you have a general idea of artillery used in the last mix-up. Don’t forget there were all kinds of guns and all kinds of howitzers and each kind had a special use in defensive or offensive work.

However, a gun was just as different from a howitzer as a revolver is from a rifle. But both were hot stuff for their own particular type of work.

And now, just a couple of words about artillery work in general and its relation to aircraft. The work can be tabulated as follows—registration on the target for future bombardment, the bombardment itself, wire cutting and trench destruction before an infantry attack, barrage fire during an attack and emergency target work. Registration on a target (range finding) and bombardment of target work were carried out in co-operation with aircraft.

The other classes of work were carried out in co-operation with ground observation or on the initiative of the officer commanding the battery. But no matter what type of work it was, the thing that counted with G.H.Q. was results. And, now that I think of it, the only thing that ever counted with G.H.Q. was results. Nix on explanations—you had to give those big pumpkins results if you wanted to stay out of hot water.

And so there you have one non-flying item that we pilots had to learn by heart. Maybe, if you are all good little children, I’ll tell you about something else that we had to absorb before they let us become Fokker fodder. Goombye!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

a story from the prolific pen of Eustace L. Adams. Born in 1891, Adams was an editor and author who served in the American Ambulance Service and the US Naval Service during The Great War. His aviation themed stories started appearing in 1928 in the various war and aviation pulps—Air Trails, Flying Aces, War Stories, Wings, War Birds, Sky Birds, Under Fire, Air Stories and Argosy. He is probably best remembered for the dozen or so airplane boys adventure books he wrote for the Andy Lane series.

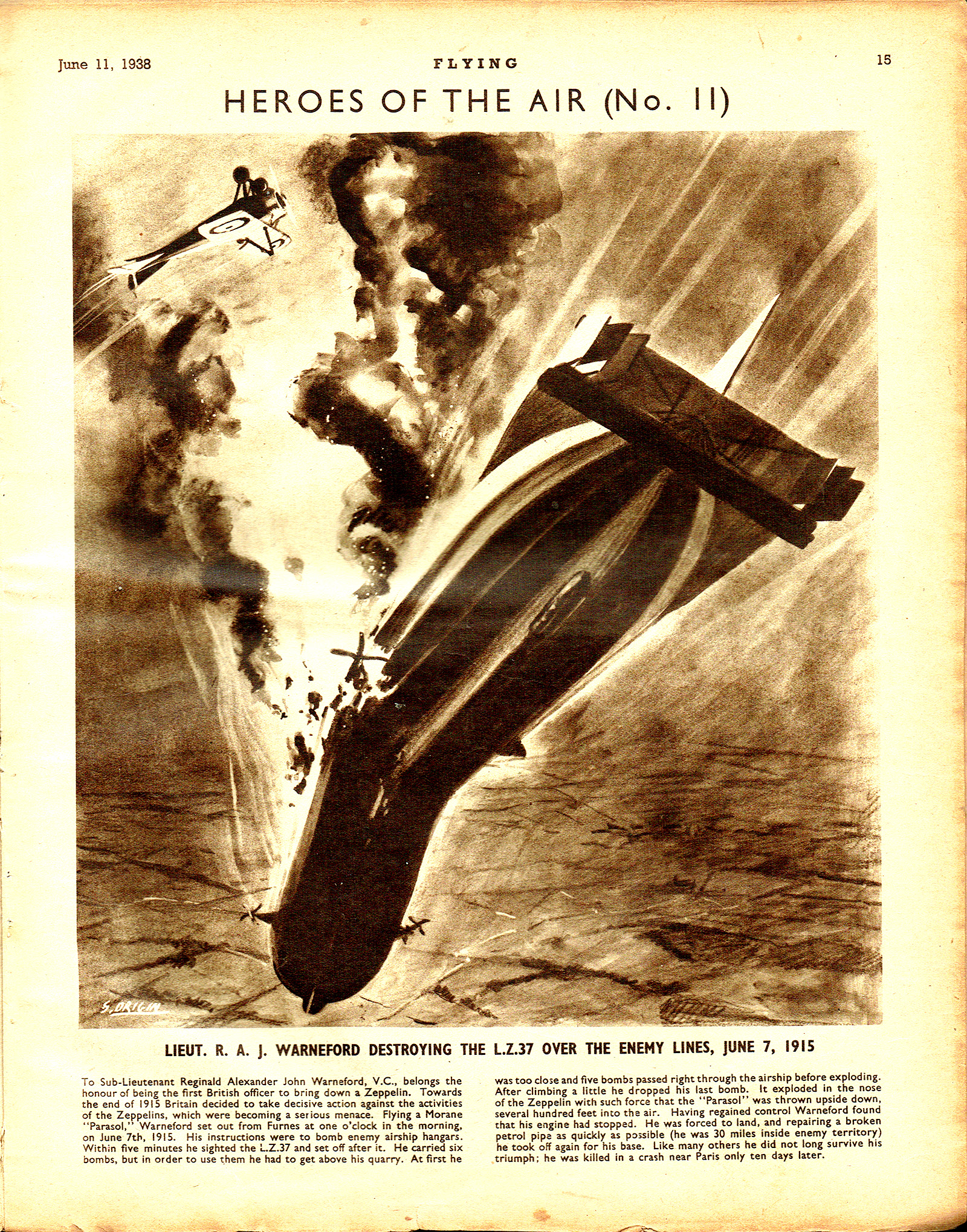

a story from the prolific pen of Eustace L. Adams. Born in 1891, Adams was an editor and author who served in the American Ambulance Service and the US Naval Service during The Great War. His aviation themed stories started appearing in 1928 in the various war and aviation pulps—Air Trails, Flying Aces, War Stories, Wings, War Birds, Sky Birds, Under Fire, Air Stories and Argosy. He is probably best remembered for the dozen or so airplane boys adventure books he wrote for the Andy Lane series. weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

a story from

a story from  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

from the prolific pen of Robert Sidney Bowen. Bowen was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, as well as the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation in addition to penning hundreds of action-packed stories for the pulps.

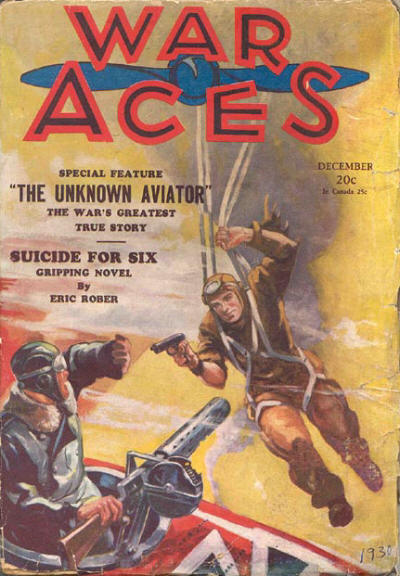

from the prolific pen of Robert Sidney Bowen. Bowen was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, as well as the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation in addition to penning hundreds of action-packed stories for the pulps. pen of the Navy’s own Allan R. Bosworth. Bosworth wrote a couple dozen stories with Humpy & Tex over the course of ten years from 1930 through 1939, mostly in the pages of War Aces and War Birds. The stories are centered around the naval air base at Ile Tudy, France. “Humpy” Campbell, a short thickset boatswain’s mate, first class who was prone to be spitting great sopping globs of tabacco juice, was a veteran seaplane pilot who would soon rate two hashmarks—his observer, Tex Malone, boatswain’s mate, second class, was a D.O.W. man fresh from the Texas Panhandle. Everybody marveled at the fact that the latter had made one of the navy’s most difficult ratings almost overnight—but the answer lay in his ability with the omnipresent rope he constantly carried.

pen of the Navy’s own Allan R. Bosworth. Bosworth wrote a couple dozen stories with Humpy & Tex over the course of ten years from 1930 through 1939, mostly in the pages of War Aces and War Birds. The stories are centered around the naval air base at Ile Tudy, France. “Humpy” Campbell, a short thickset boatswain’s mate, first class who was prone to be spitting great sopping globs of tabacco juice, was a veteran seaplane pilot who would soon rate two hashmarks—his observer, Tex Malone, boatswain’s mate, second class, was a D.O.W. man fresh from the Texas Panhandle. Everybody marveled at the fact that the latter had made one of the navy’s most difficult ratings almost overnight—but the answer lay in his ability with the omnipresent rope he constantly carried. another story from one of the new flight of authors on the site this year—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War and worked for the air mail service upon his return, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the 1920’s through 1950. For the second issue of Sky Birds, Caffrey tells the story of Lieutenant Mike Harris—a.k.a. “Coupe Mike” due to his proclivity to overuse the coupe button during his training—fresh up from Issoudon after extensive training.

another story from one of the new flight of authors on the site this year—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War and worked for the air mail service upon his return, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the 1920’s through 1950. For the second issue of Sky Birds, Caffrey tells the story of Lieutenant Mike Harris—a.k.a. “Coupe Mike” due to his proclivity to overuse the coupe button during his training—fresh up from Issoudon after extensive training.

MY LONG-LOAFING experience was started back in Lawrence, Massachusetts, on the coldest March the eleventh that 1891 knew. That makes me twenty-one by actual count.

MY LONG-LOAFING experience was started back in Lawrence, Massachusetts, on the coldest March the eleventh that 1891 knew. That makes me twenty-one by actual count.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!