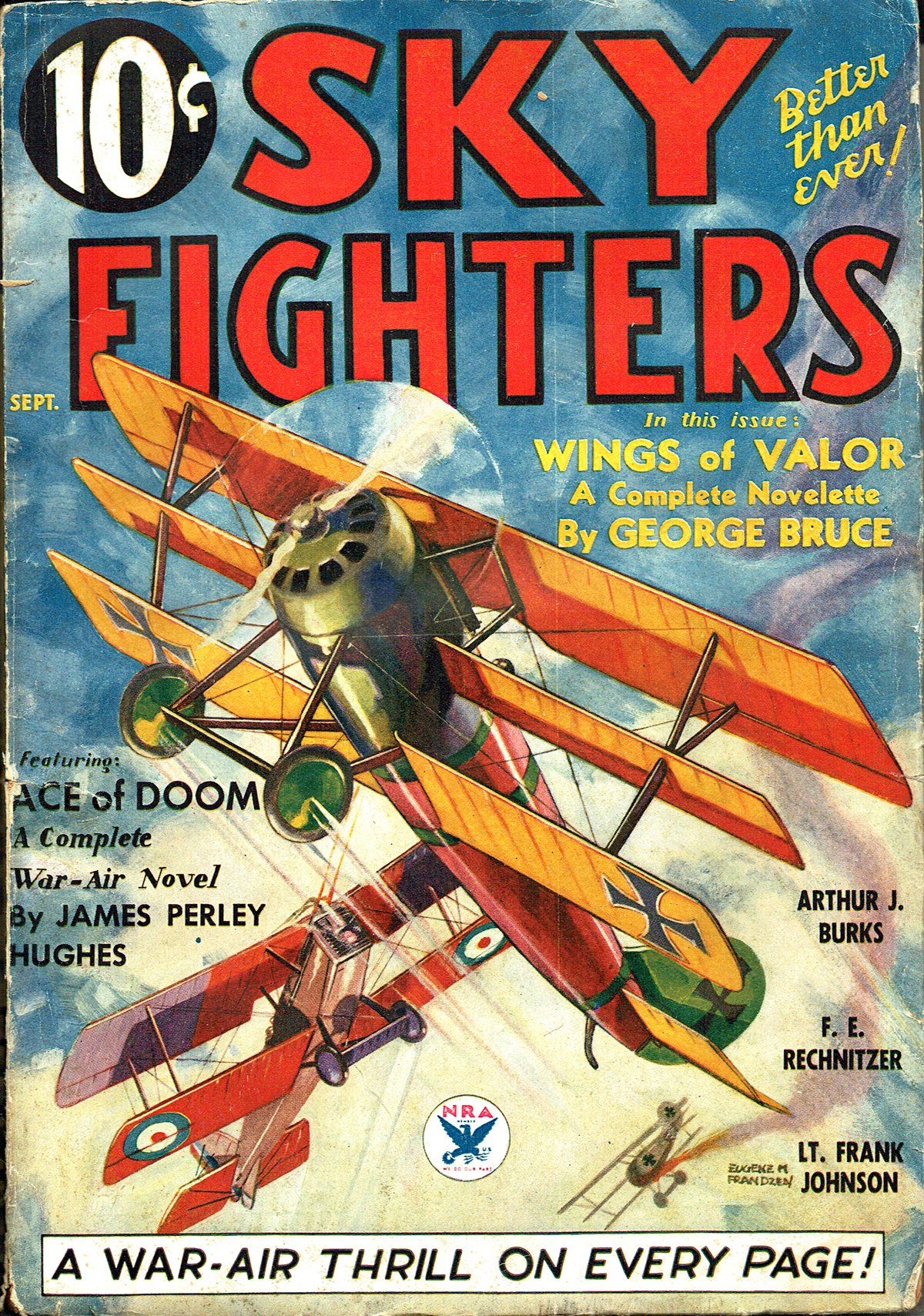

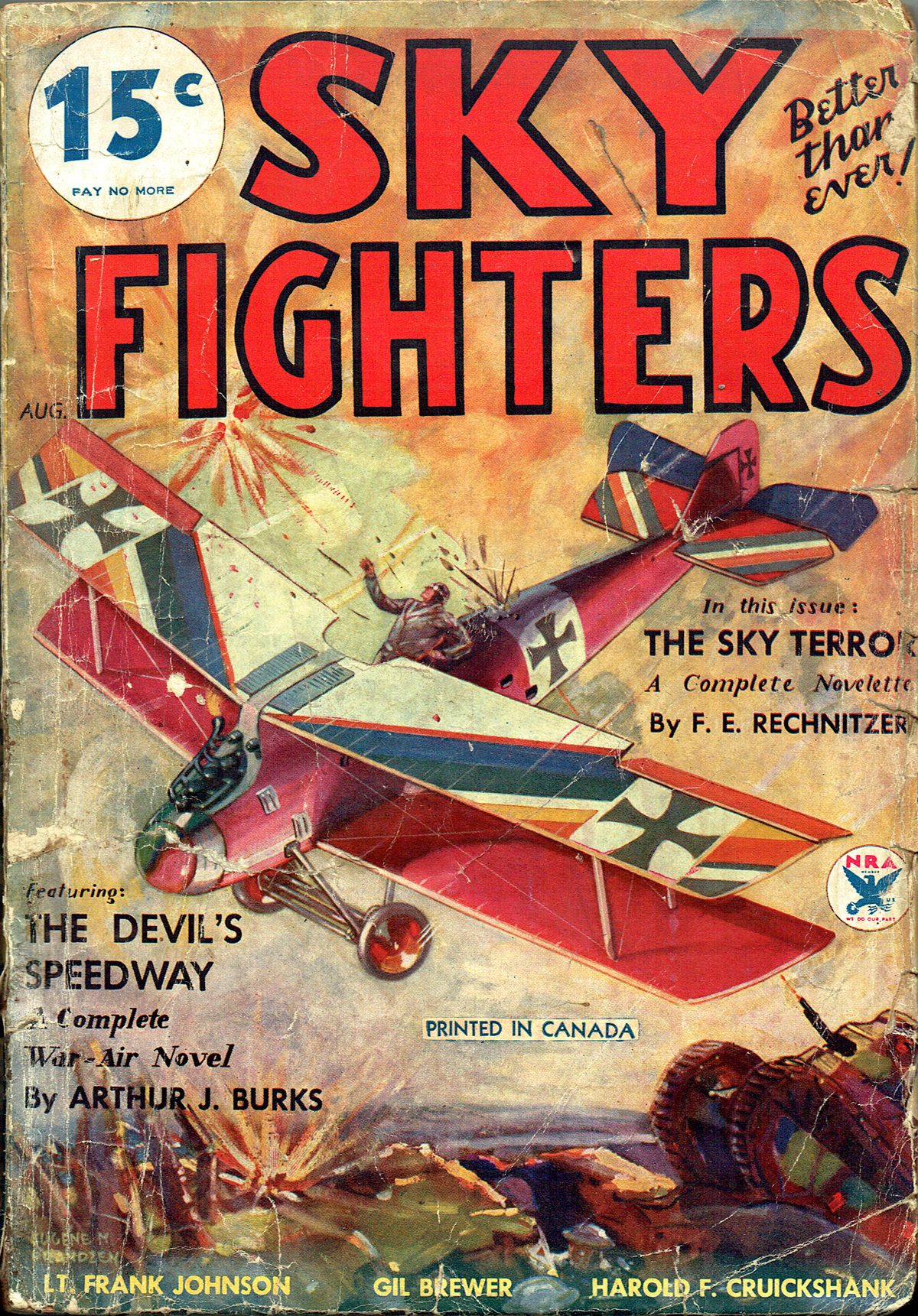

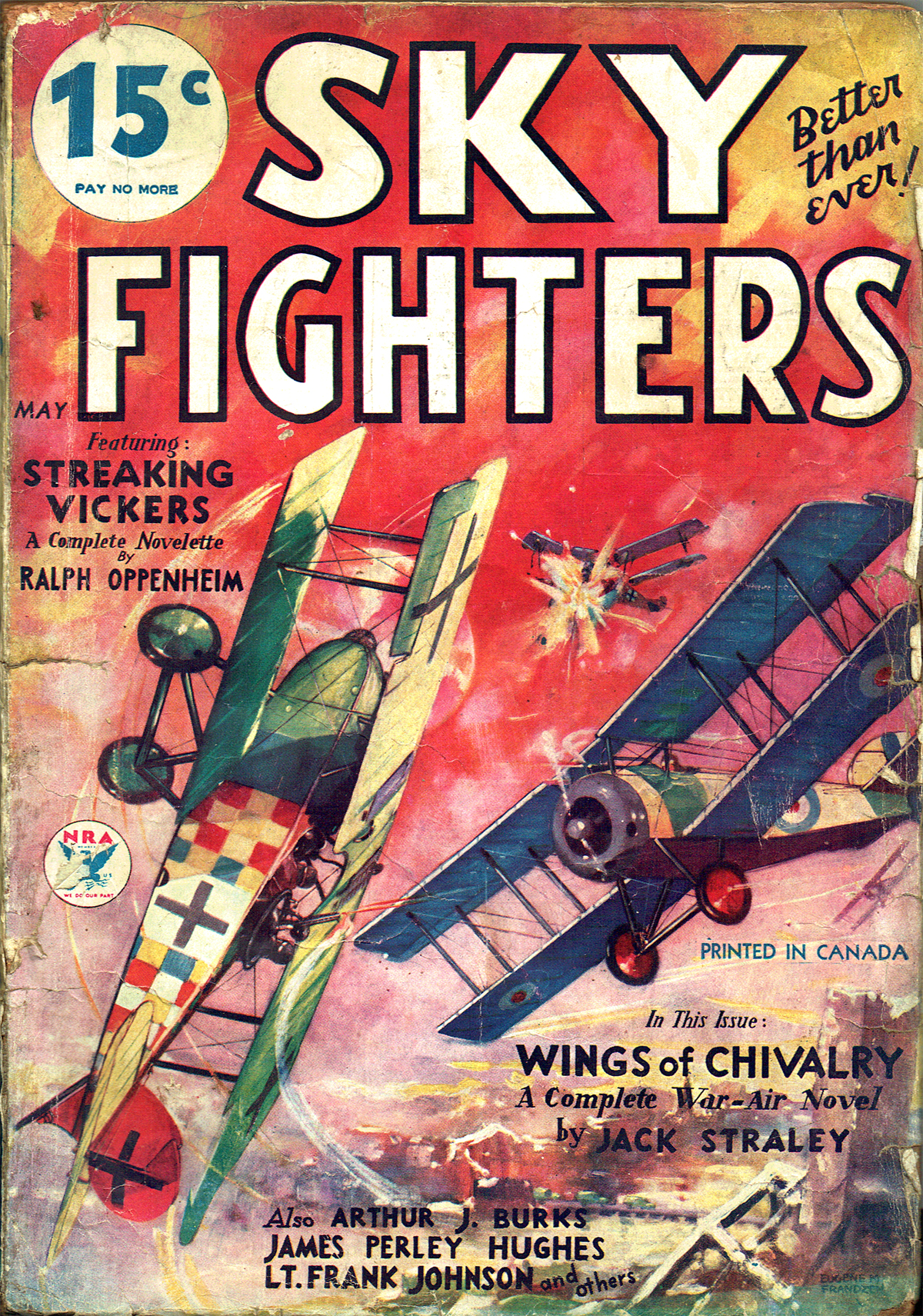

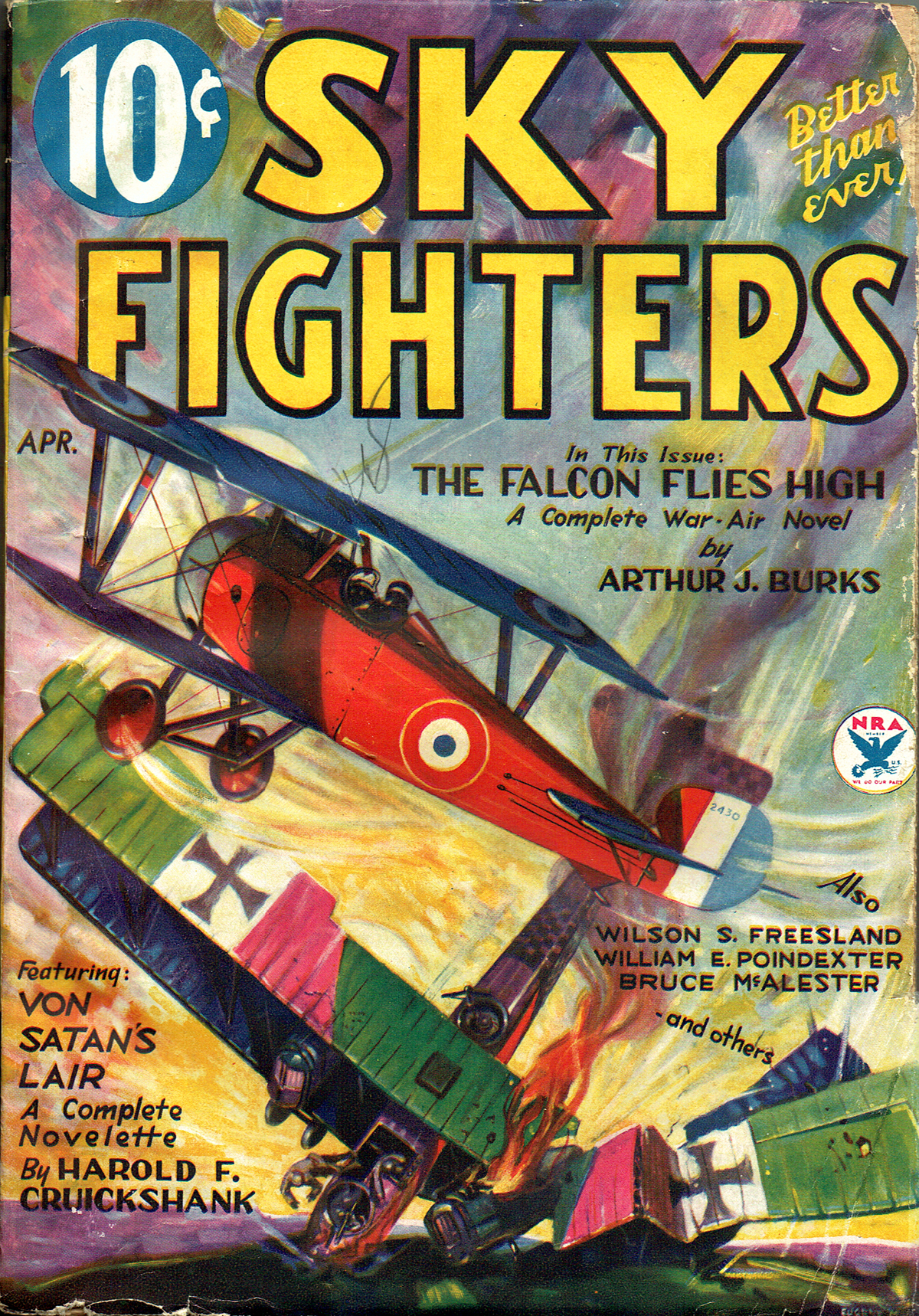

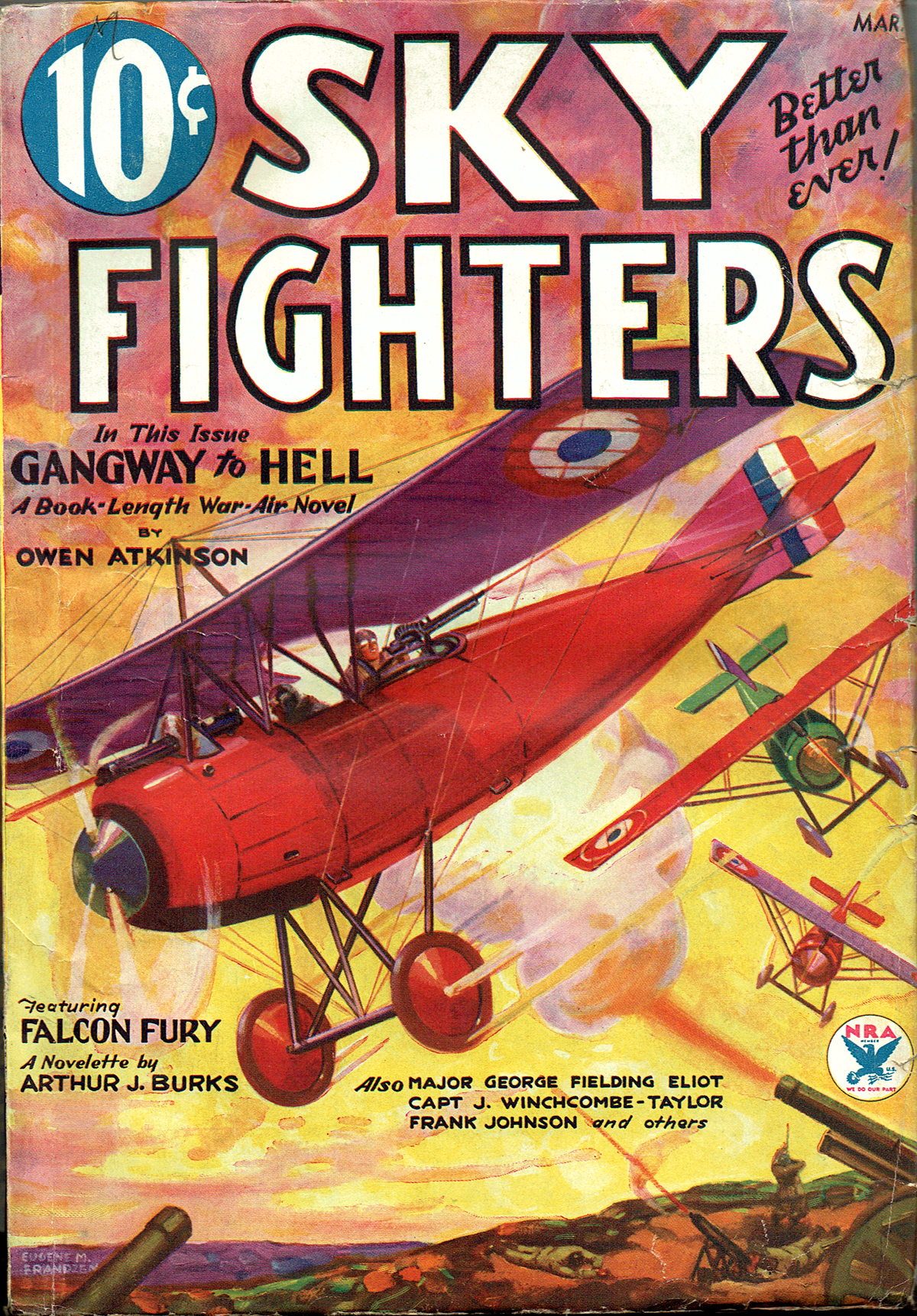

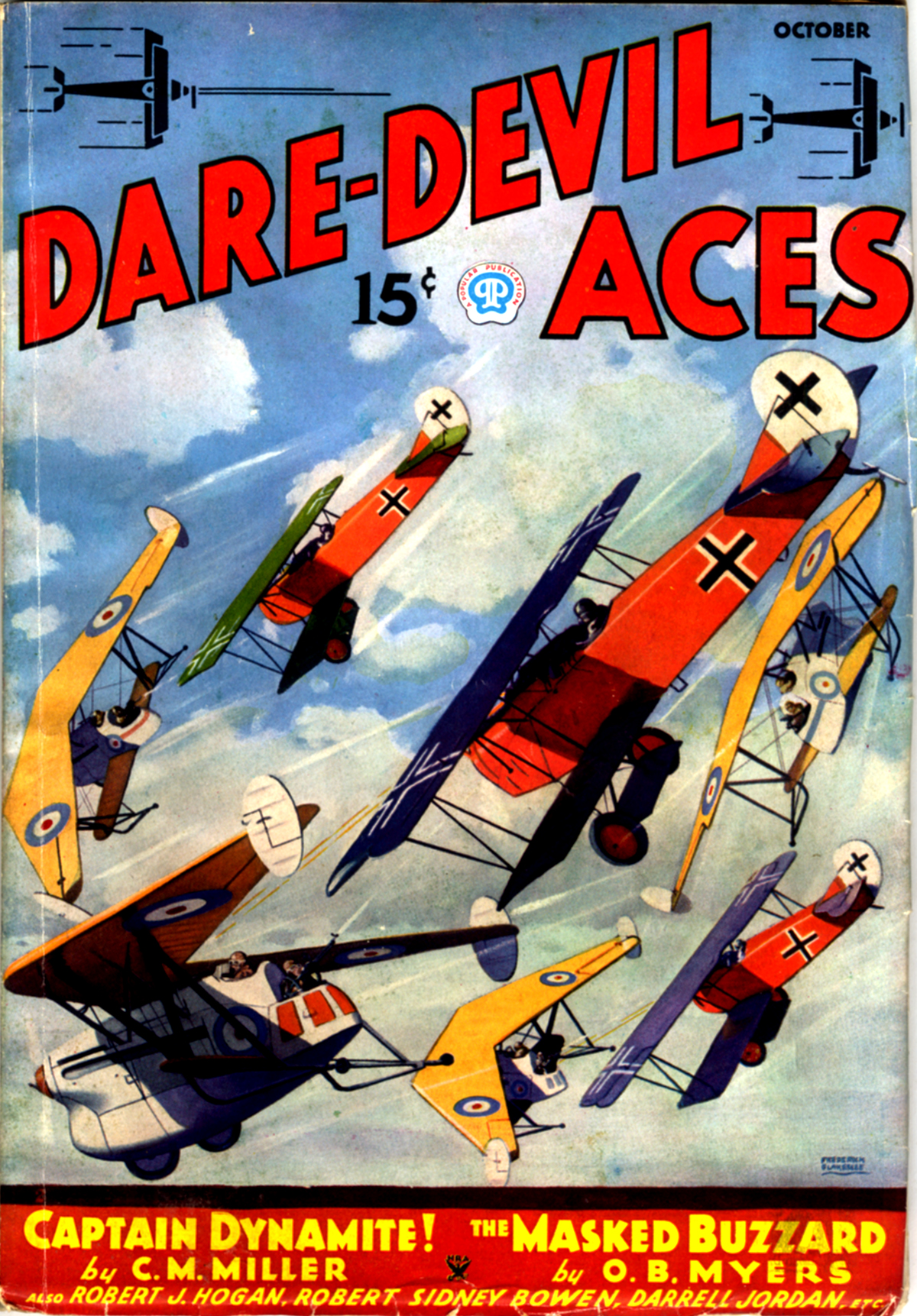

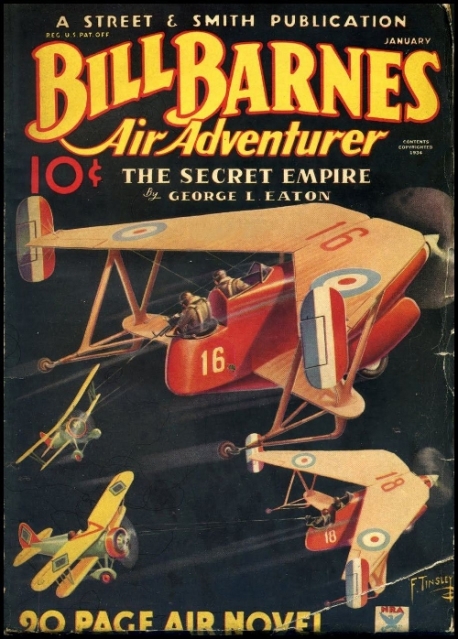

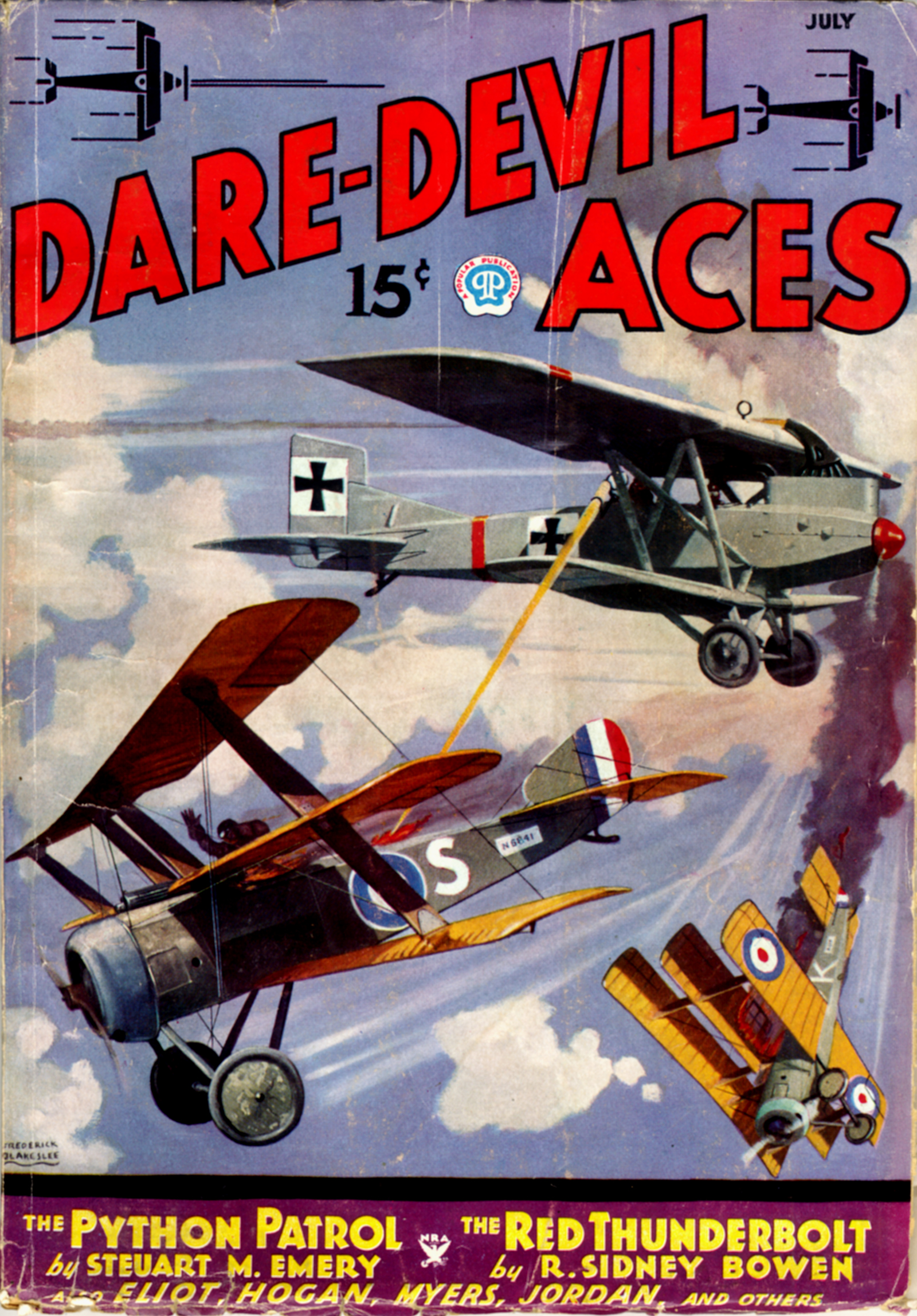

“Sky Fighters, October 1934″ by Eugene M. Frandzen

Eugene M. Frandzen painted the covers of Sky Fighters from its first issue in 1932 until he moved on from the pulps in 1939. At this point in the run, the covers were about the planes featured on the cover more than the story depicted. On the October 1934 cover, It’s the Halberstadt C.L.2 vs the Avro “Spider”!

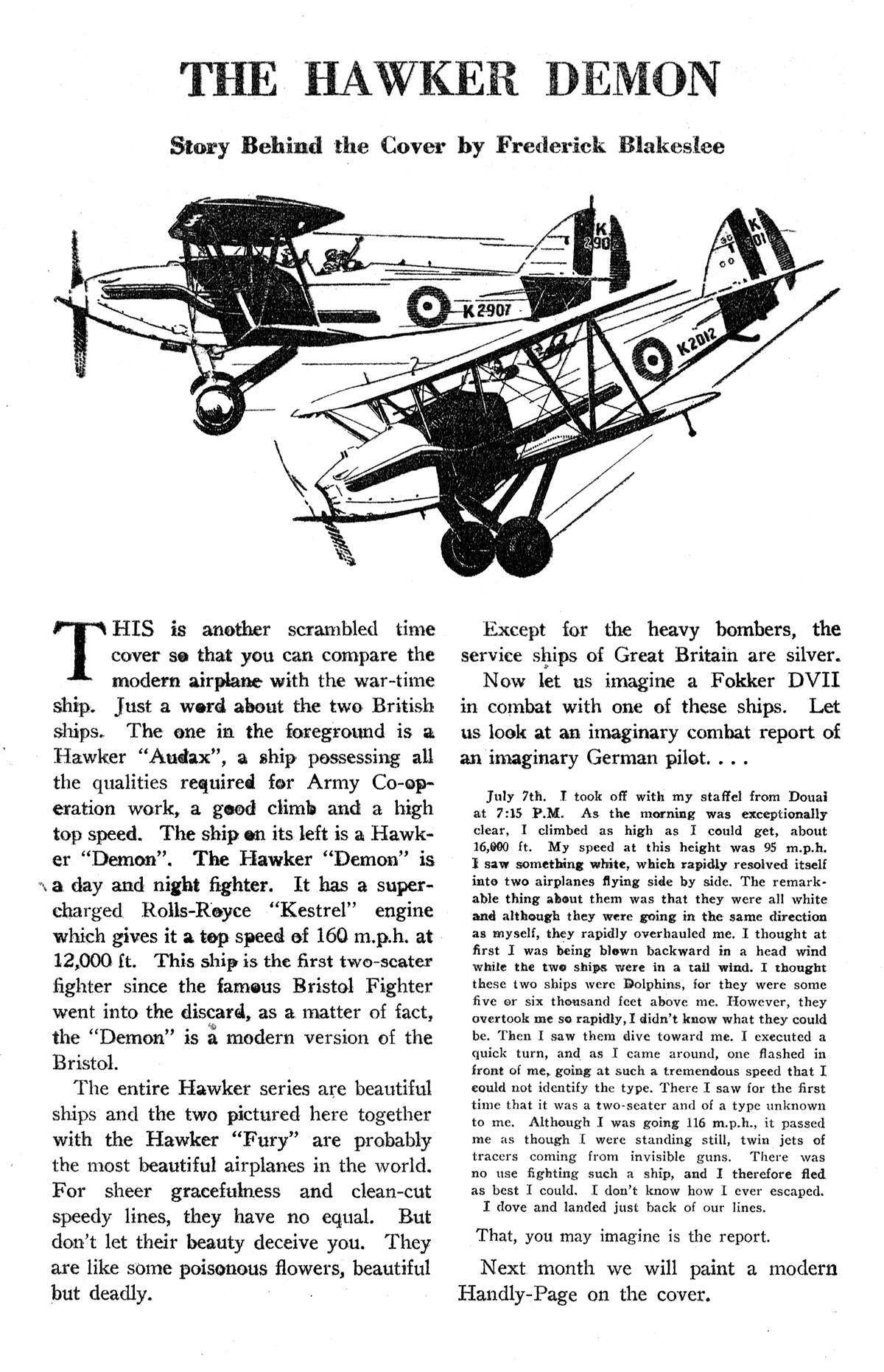

The Ships on the Cover

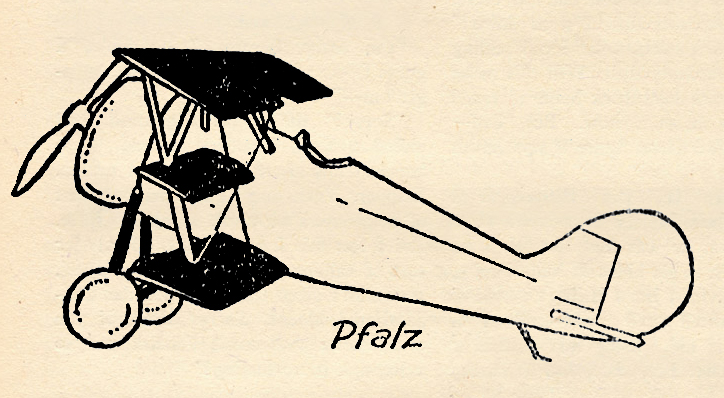

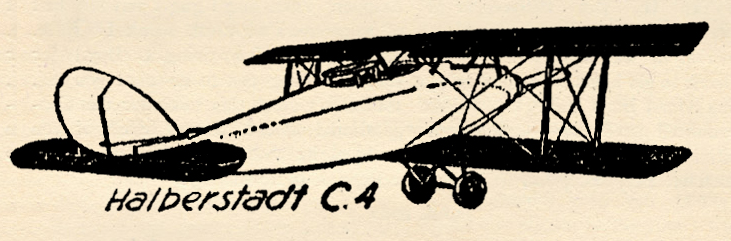

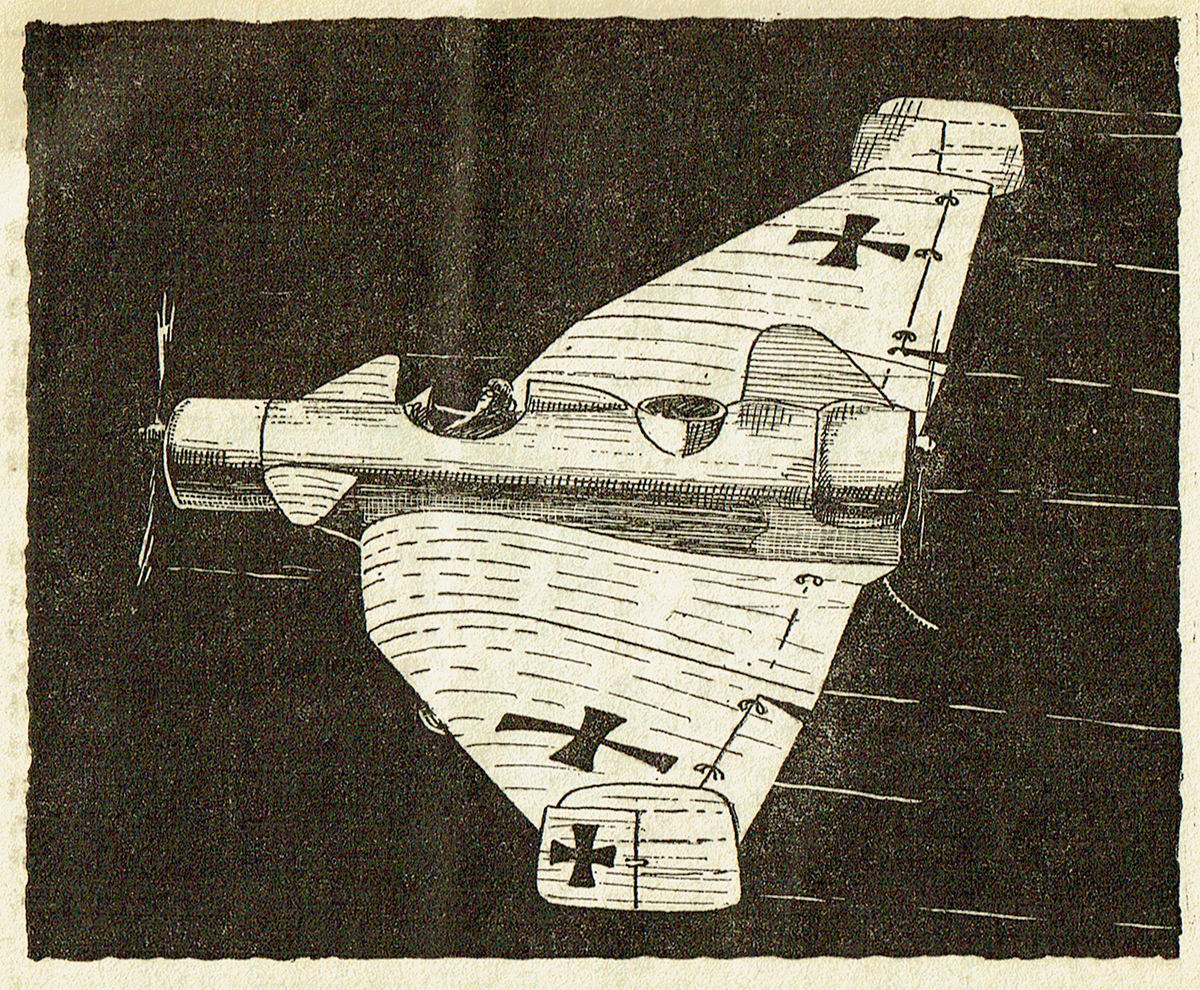

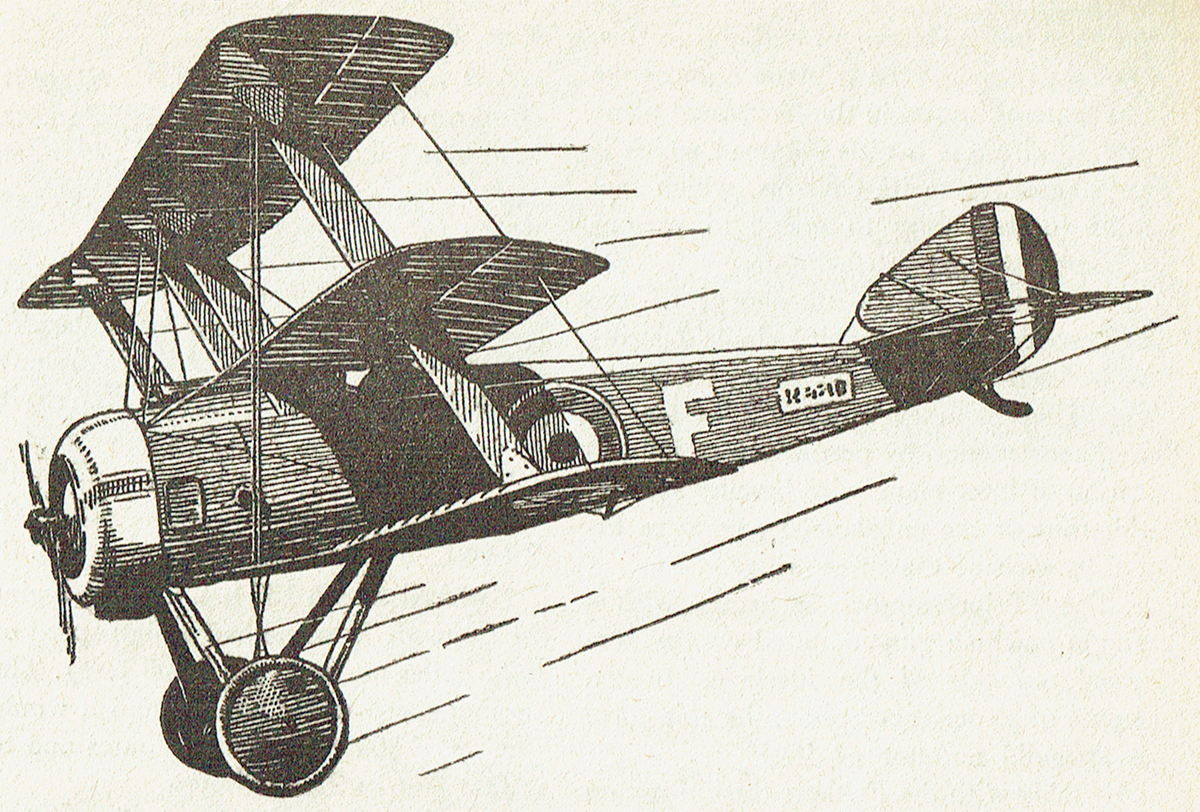

THE Halberstadt C.L.2 was,  with its sister ship the C.L.4, a bright spot in Germany’s output of two-seater fighters. It was simpler in design than most of the German ships of this type; probably thereby lays the reason for its very good performance. Kicking over 1,385 r.p.m.’s at 10,000 feet, it could travel at around 100 m.p.h. It was not so hot on climbing, but was light on its controls and could be maneuvered with ease.

with its sister ship the C.L.4, a bright spot in Germany’s output of two-seater fighters. It was simpler in design than most of the German ships of this type; probably thereby lays the reason for its very good performance. Kicking over 1,385 r.p.m.’s at 10,000 feet, it could travel at around 100 m.p.h. It was not so hot on climbing, but was light on its controls and could be maneuvered with ease.

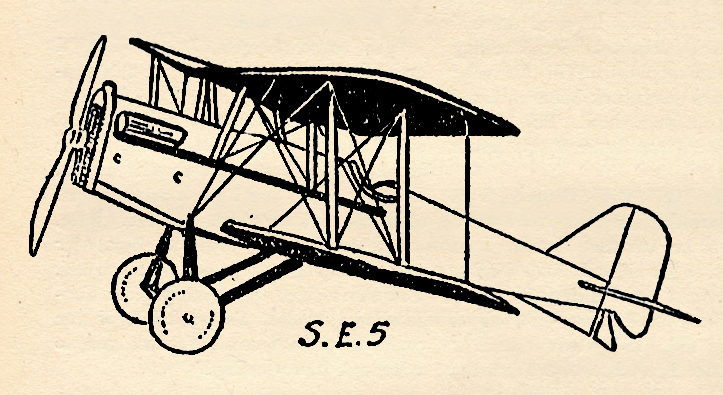

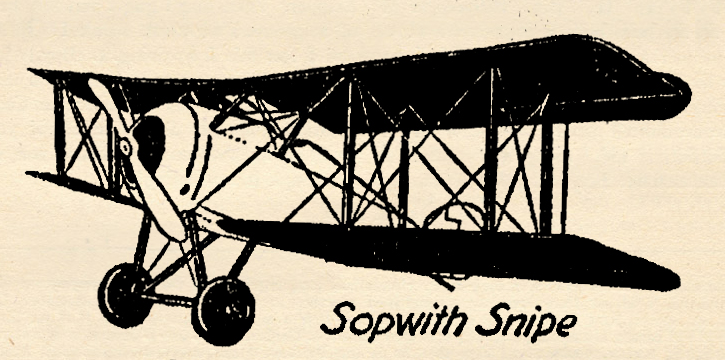

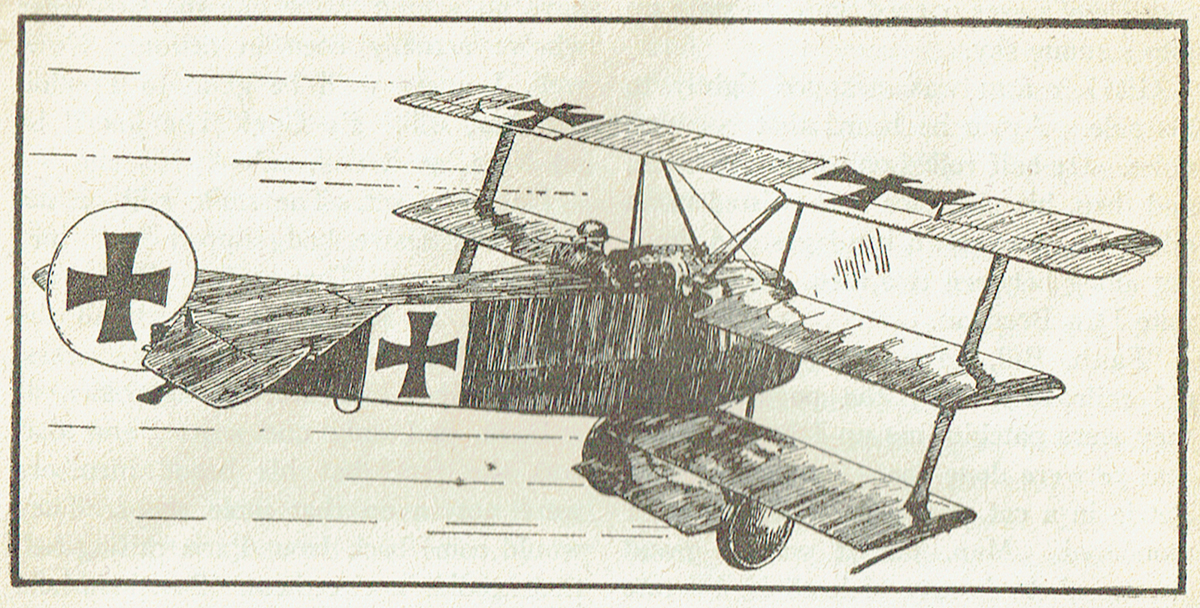

The other ship on the cover is the Avro “Spider,” a job turned out by the famous A.V. Roe & Co., Ltd. It had “It” when it came to speed, maneuverability, and climb. Its trick triangular system of inter-plane bracing obviated the use of flying or landing wires. And when it came to visibility that “one holer” in the top wing gave the pilot a look-see up and ahead. Even downward vision was good as the chord of the lower wing was very narrow.

Let’s slip back about half an hour before this crackup that’s pictured on the cover.

A Trophy of War

Consider yourself planked on an Allied tarmac. Out in front of number one hangar is a captured German ship; a Halberstadt. A group of British aviators are standing around admiring their trophy. Greaseballs have tuned her up, she is idling beautifully. One of them with three pots of colors is ready to paint the British cocardes on this German ship. There is darn good reason for this art work on captured machines. It’s to save the Allied test pilots who take up the captured ship back of the lines from getting popped down by some other Allied aviator who might think a German was at the stick.

Standing among the British aviators is a young man with a very dejected expression on his square face. His goggles are shoved back. His collar ornaments are German. To the Allied aviators, whose captive he is, he is just a flyer who happened to work for the wrong side. Much wine and spirits have trickled down all throats since the capture of the German. All hands are buddies, friends; in fact old pals. What if Fritz did pop at them from his Halberstadt? It was all in the game.

Just a Joy-Ride

“Let’s have a little ride in your old war chariot, Fritz,” suggested Lieutenant Mills, who had forced the German down.

So Fritz climbed in at the controls after it was certain his front and rear guns were harmless. Lt. Mills tucked a pistol into his pocket and heaved himself up on the side.

Smack!

Fritz fist clipped the Britisher on the button. The Mercedes roared. Dirt blasted into the other’s eyes on the ground.

An Avro roared throatily in the next hangar. Lt. Mills was in it in a jiffy, gunned the Bentley and blasted down the drag and up into the air. It took him twenty minutes to catch Fritz. Then came ten minutes of systematic sniping at engine and wings. Finally the Halberstadt’s engine sputtered, died. Down she came, flopping and shuddering. As her undercarriage hit the ground her wings folded and called it a day. Lt. Mills landed close by, rubbed his aching jaw and walked over to the wreck. Fritz crawled out, felt himself all over and indicated that he was not injured. He then shoved out his jaw and Lt. Mills carefully planked a beautiful right uppercut home. Fritz took it standing up and grinned.

Mills produced a flask—”Cheerio,” he grinned.

“Prosit,” replied Fritz.

Sky Fighters, October 1934 by Eugene M. Frandzen

(The Ships on The Cover Page)

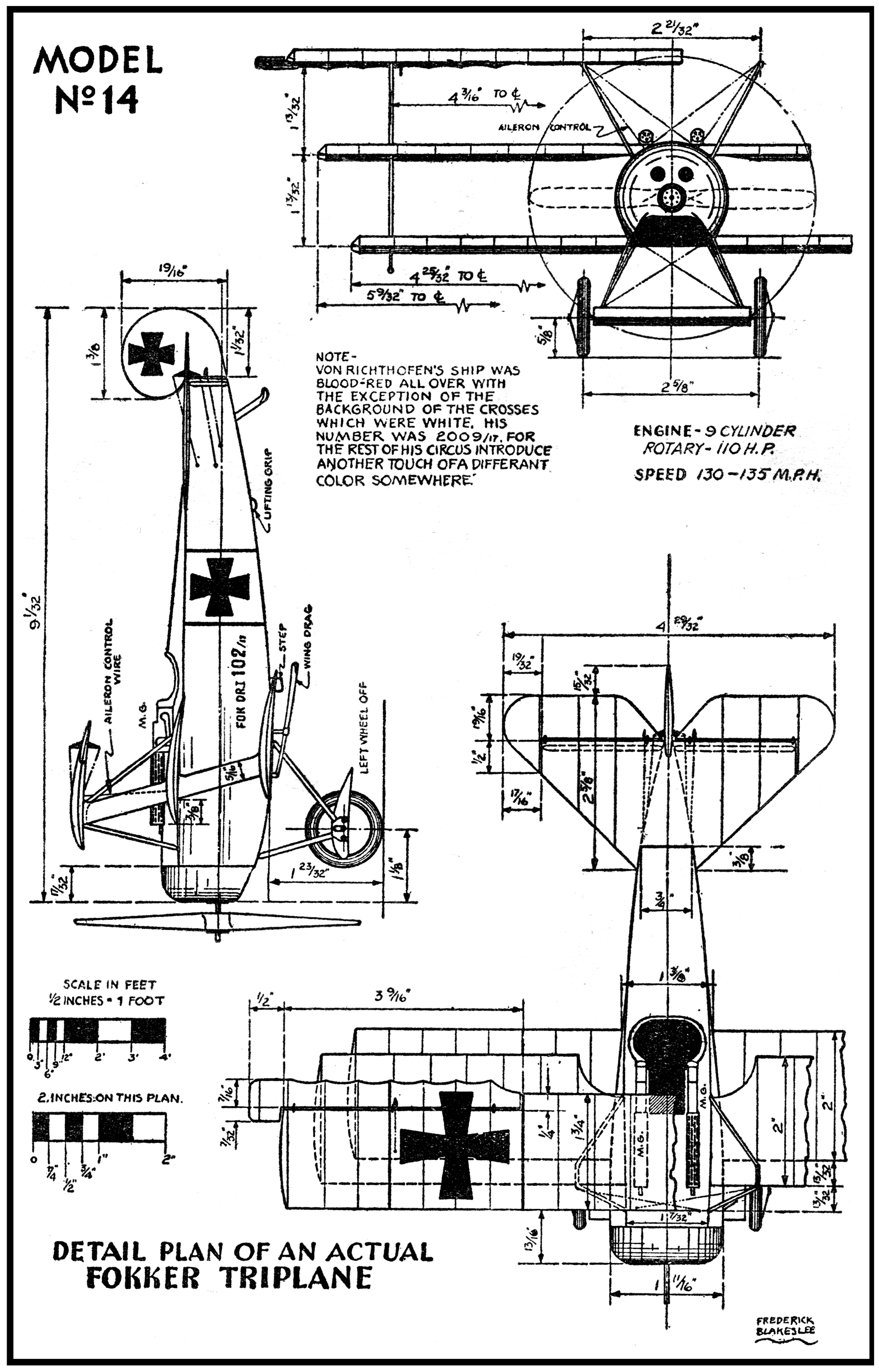

Next time, Mr. Frandzen features the Fokker E.1 and the F.E.2!