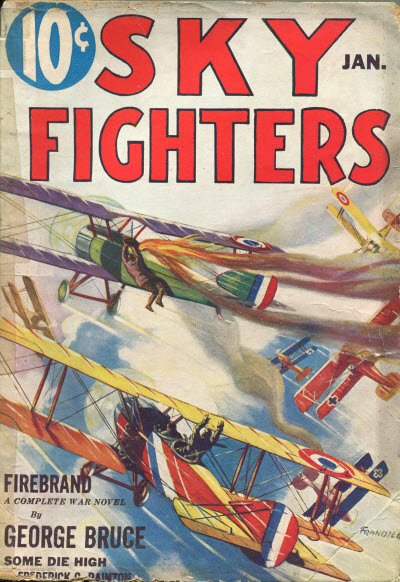

FROM the pages of the January 1933 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

Top Man Wins… Maybe!

by Robert Sidney Bowen (Sky Fighters, January 1933)

WELL, I’ve had you upstarts under my wing for so long now that I guess I can’t call you fledglings any longer. Of course there are some of you who are worse than fledglings. But still some others of you have been paying attention, and have actually learned a thing or two about this business of war flying, and what have you. So from now on I’ll consider you all as promoted to the next grade, and call you buzzards. But, mind you, any cracks out of turn, or any funny business, and back you all go to the rank of fledgling. And take it from Uncle Wash-Out, there ain’t nothing lower in a pilot’s estimation than a fledgling. Okay, buzzard—here we go!

A few chinfests back (the C.O. of this mag will give you the exact date) I told you the hows and whys of Getting Your Hun. The main point I leaned on was the great amount of preparation before you even took your crate into the air. Well, this time I’m going to deal with technical points after you get upstairs and spot your man.

Now, read this over.

“Spandaus guns yammered savagely and twin streams of fire reached out for the Yank ship. But the pilot in that Yank plane was not to be caught napping. Slamming into a half roll, he immediately came out of it and zoomed up to cartwheel over and go plunging straight down on the German ship, his Vickers singing their song of death. It was all over then, for the Yank was top man, and top man always wins!â€

Does that sound familiar? Sure it does! You’ve read something more or less like that in fifty different stories. But here is where I step into the picture and maybe make myself the nasty antipathy of a whole lot of your favorite authors. And maybe before I get through, the C.O. of this mag will toss me into the klink and get a greaseball to double for me. But, come what may, I’ve got to be honest with you buzzards. In these chinfests I’ve got to stick to the technical truth. In others words, I’ve got to be on the up-and-up. Now, don’t get the idea that I’m only trying to pick your stories apart. That’s not the idea. I’m just going to elaborate on points that your authors didn’t have time to enlarge upon. Their stuff is fiction—action—boom-boom stuff—and all the rest of it. But my stuff is straight stuff. Oh, maybe dry in spots, but the true dope.

Okay, lean on this. Top man in a scrap does not always win!

The method of getting an enemy ship depends upon a lot of things. The most important thing is what kind of a ship it is. In other words, you don’t go after two-seaters the the way you go after a pursuit ship. And you don’t go after a pursuit ship the way you go after a bomber. And you don’t go after any of them the way you go after a balloon.

Of course, there is one item that applies to them all. That is, getting the old machine-gun bullets in where they will do the most damage. But thinking about it and accomplishing it are two different things.

Now, for example, let’s take the case of two pursuit ships scrapping it out. Let us say that the Hun comes in from the east, and you come in from the west. You are both at the same altitude and you spot each other at the same time.

WELL, naturally, both of you will start to climb. The more altitude you have the more advantage you have. (Don’t forget, now, I’m talking about pursuit ships.) Why is altitude an advantage? Well, buzzards, as I’ve told you many times before, a pursuit ship pilot can only shoot his guns in one direction—forward. Therefore, he has no protection at the rear. It stands to reason, then, that the ship with the most altitude has the better chance of maneuvering down on the other’s tail, or as it is often called, his blind spot.

But in this case we’re talking about, we’ll say that neither you nor your enemy get greater altitude. You draw close together at the same level. Well, you both probably take nose to nose shots at each other. Scoring any damage that way is not common occurrence for the simple reason that you are both protected by a wall of metal. And that wall of metal is your engine. Also, a plane coming dead on to you presents a mighty small target. If you don’t think so, well, the next time you go up fly nose to nose with some other ship and take a good look for yourself. Fig. 1.

WELL, you can bring your enemy down by flying right into him. But that would mean curtains for you, too. And, besides, ten times out of ten, your enemy doesn’t want to cash in that way. So he pulls out of the way at the last minute. Usually he zooms up in a climbing turn, hoping to drop down on your tail. Well, you beat him to it and do the same thing yourself. And what’s the result? You have both gained altitude, and you have dropped into what the boys used to call the ring-around-rosey, or the tail chase tail formation.

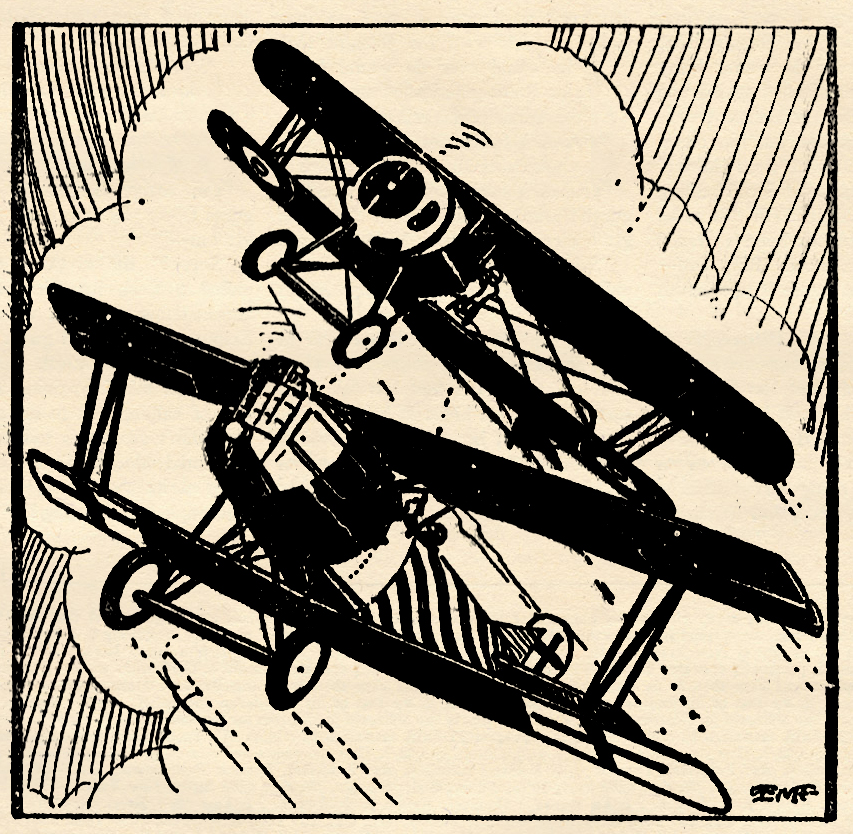

Take a look at Fig. 2, and you’ll see what I mean. You both are on the outside of circle, headed in opposite directions, and chasing each other’s tail around in the air. Naturally, you both are trying to get around faster than the other so that you can plant a nice little telling burst in the other’s tail. But you find out that the other ship has just as much speed as you have, and the result is that you both stay on opposite sides of a big invisible circle.

All right, buzzards, I know what you’re going to ask. So sit down, and I’ll tell you. Why not shorten the diameter of your circle? In other words, why not bank more sharply? Well, it’s a swell idea if you can do it. And if you can, why of course you have a beautiful broadside shot at your enemy. But just remember that your enemy isn’t flying around and reading a copy of SKY FIGHTERS. Not by a long shot. If he’s a good pilot he’s trying to pull the same stunt on you!

WELL, of course you can’t keep on going around in a circle all the time. If you keep it up long enough you’ll both starve to death. So someone has to break the circle—bust up the ring-around-rosey idea. But whoever breaks it has got to be quick and careful. Once you pull out of it your opponent has a couple of precious seconds in which he can whip around and let you have it.

One of the best ways to do that (as proven in the late Big Fuss) was to pull up and over toward the inside of the ring. In other words, you try to climb up and come down on top of your man. His defense against that is to do the same thing himself (and bring both of you right back where you were) or else to whip over and down and then up. The idea being to get you from underneath before you can bring your guns down to train on him.

RIGHT there is a good example of what I said at the beginning. If your enemy should be successful in whipping down and up before you whipped up and down, why it would be a case of top man getting it in the neck.

In view of the fact that I’ve illustrated my top man idea I’ll end this scrap by saying that you catch him napping and shoot his pants off, and his life along with them. That, of course, is the final thing in every scrap—I mean, that one or the other pulls a surprise maneuver that catches the other napping and allows the chance for the killing burst.

But before I speak about observation ships, I want to point out another example of top man not winning. Suppose when you break the circle by zooming up and over and your enemy slams into a quick half-roll and dives away. Well, of course, he takes a chance that you may be able to slide around and get him. But he has a few precious seconds in which to get up a lot of diving speed, before you are in a position to dive after him. The result, of course, is that you are top man, but your enemy is diving away from you, putting air space between you and him, which means a longer range shot for you. And not only that—he presents a rotten target. He is edge on to the ground, and you’d be surprised how a ship diving away from you seems to melt in with things below on the ground. The ground is dark and the outline of parts of the ship presented to you are also dark. In other words, the ship forms no silhouette, like it would if there was a background of sky or clouds. To get the idea, look at Fig. 3.

And now for the two-seater ships.

YOU are patroling around and suddenly you see an enemy two-seater taking pictures behind the lines. Naughty! naughty! That pair of young men must be taught a very lasting lesson right pronto! So you go down after them. But do you drop down on their tail?

Well, if you do and they see you coming, you won’t need to worry any more about how you’re going to pay your losses in that poker game in the mess last night. And why? Well, buzzards, there is an observer in that two-seater, parked in the rear cockpit. And when he left his home drome he took along at least one, and probably two, guns mounted on a swivel mounting that enables him to shoot in any direction except forward and down. And you can bet your sweet life that he still has them with him. So, if you come piling down from the rear and he sees you, well, you’re just going to get a whole mouthful of bullets that won’t taste good.

OF COURSE, there is an exception to everything, and it is possible to pile down on an enemy two-seater from the rear, and pop it right out of the sky. But such a case is only when the occupants of that two-seater are napping, or are too busy doing something else, and therefore fail to see you before your bullets are slapping into them. Such an occurrence could happen, if you got the sun at your back. In that case its brilliance would blot you out of their sight.

But enough of what you shouldn’t do. Let’s get on with what you should do.

In this case we’ll say that it is not a surprise attack. The enemy sees you coming. Well, no matter what angle you come down from, you will be in their range of fire. And naturally you cannot come down to their level though out of range, and then bore in from the side, for the simple reason that a two-seater doesn’t have to go into any ring-around-rosey maneuver. It doesn’t, because the observer can train his guns on you while the pilot flies the ship dead ahead.

All right, buzzards, all right! I’m getting to it, so keep quiet.

The thing to do is to attack the two-seater in its blind spot. And the blind spot of a two-seater is the area underneath the ship, extending from the prop to the tail skid. Neither pilot nor observer can bring their guns to train on any part of that area. And so the idea is to dive down under the two-seater and come up at it from underneath. In other words, hang on your prop and plant your burst right smack through the floorboards of that two-seater. And no matter which way, he goes, you just try and keep in that blind spot. Fig. 4.

And so I murmur again—what do you mean, top man always wins?

Now for bombers. And are those babies tough! Present-day bombers, as you buzzards probably know, have about as many blind spots as a goldfish bowl. And the old wartime bombers didn’t have so many themselves. About the only blind area they presented to attacking planes was directly under the forward parts of the ship, and close up under the wings.

And so you won’t be misled, let me tell you that the best way to get one of those big babies was to take along a couple of your squadron pals with you. The idea being that while a couple of you worried the occupants of the bomber the rest would pile in from the side they weren’t looking at, and get in your shots. But should you be alone, the best way was to take your pot shots from underneath. Top man wins, eh? Oh, yeah?

NOW, before I rush myself away from you, I’ll just mention a word or two about top man and balloons. Getting a balloon is a job that really is ninety-nine and nine-tenths surprise. You have several factors against you. First, the men in the balloon are keeping a sharp eye out for you. Second, the ground defense of that bag is also keeping a sharp watch for you. Third, it is possible for the bag to be hauled down before you can close in on it. Fourth, you can be exposed to terrific fire from the ground. Therefore, the bigger the surprise, the better chance you have of getting the bag.

LET’S say you pile down on it, and miss. Meantime you are diving through lead hell—that lead hell doesn’t miss. Well, you may be top man, but it’s curtains, unless luck is with you and you can fly clear before you’re struck in a fatal spot.

Well, let’s attack another way. Fly close to the ground (making it hard for the men in the bag to spot you against the ground, and completely hidden from the bag’s ground forces), then at the last moment zoom up at it and let drive. Your shots go home and the bag goes blooey. It was top man, wasn’t it? And in the meantime you are top man to the ground forces, and they may nail you before you can zoom out of range. Fig. 5.

So, as I said at the beginning—it depends upon a lot of conditions and cirmustances whether the top man wins or loses. In most scraps it is favorable to be top man—but that rule does not hold good all of the time—and don’t let Santa Claus tell you that it does!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

a story from the prolific T.W. Ford. Ford wrote hundreds of stories for the pages of the pulps—westerns, detective, sports and aviation—but best known for his westerns featuring the Silver Kid.

a story from the prolific T.W. Ford. Ford wrote hundreds of stories for the pages of the pulps—westerns, detective, sports and aviation—but best known for his westerns featuring the Silver Kid.

another of

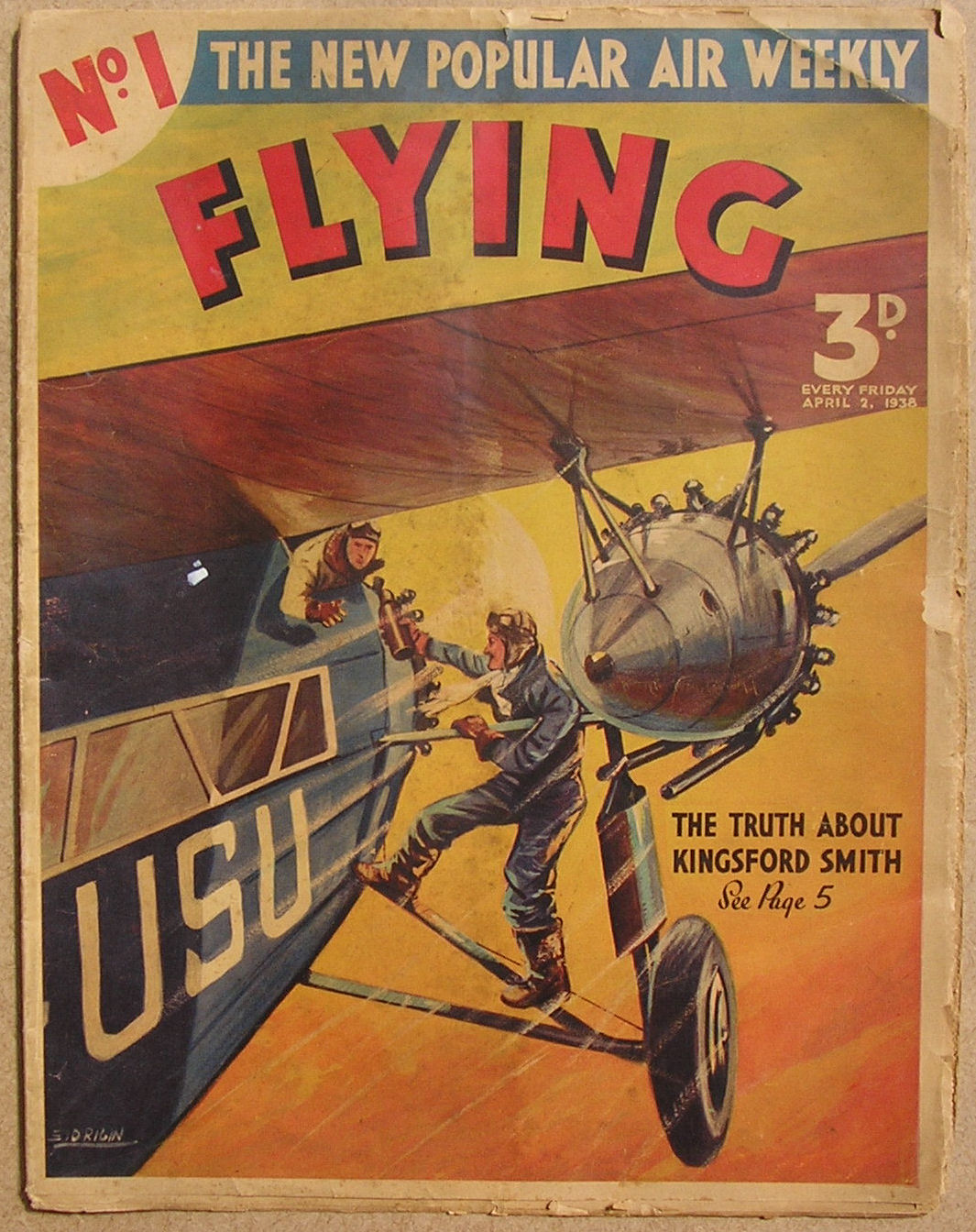

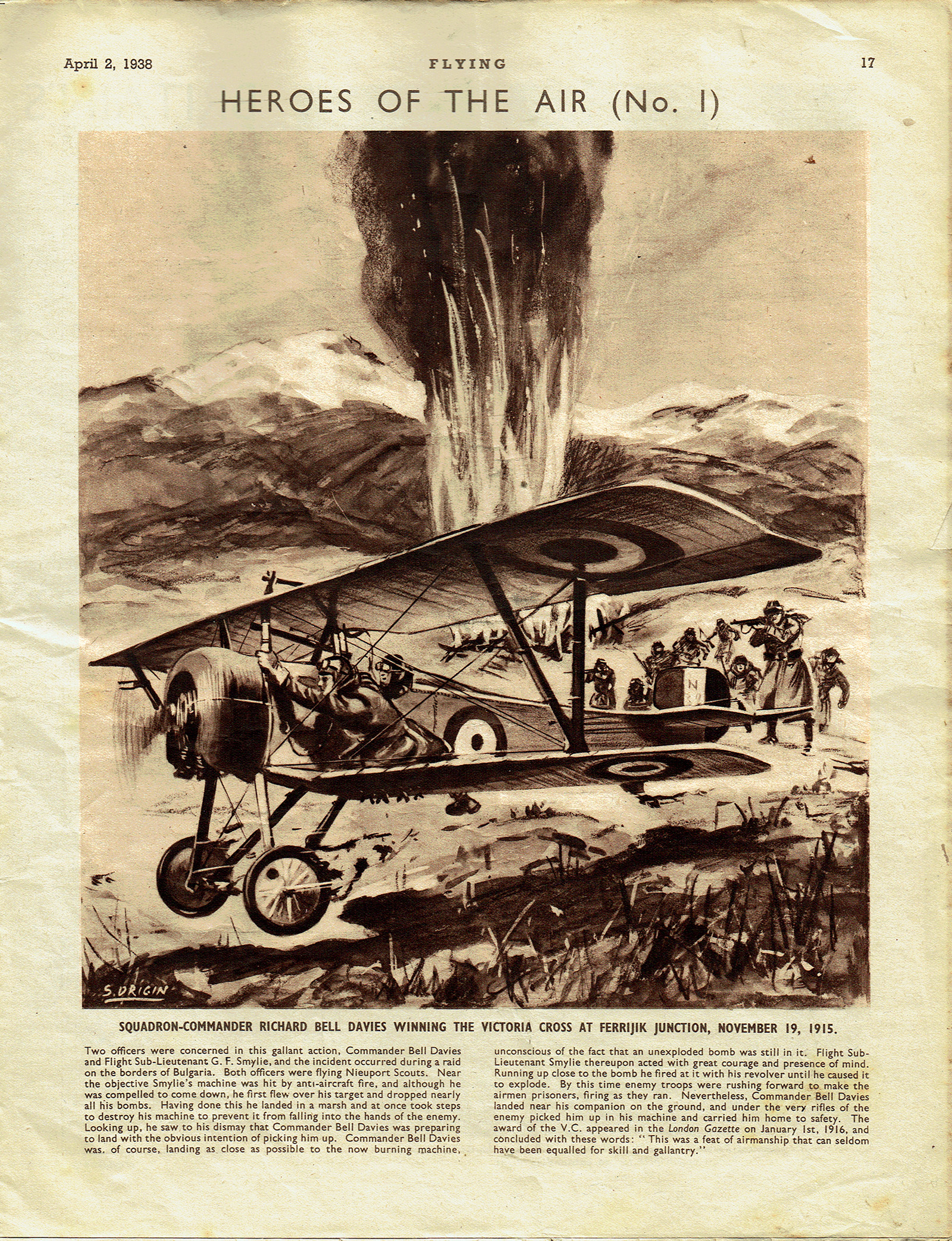

another of  weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

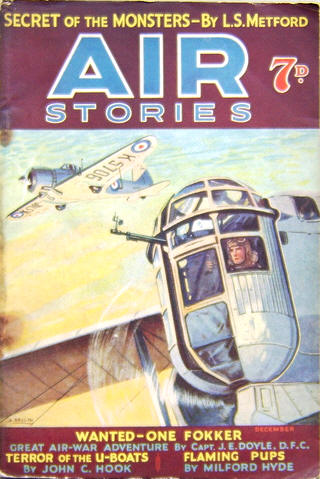

a story from the pen of British Ace,

a story from the pen of British Ace,  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

another gripping tale from the prolific pen of

another gripping tale from the prolific pen of