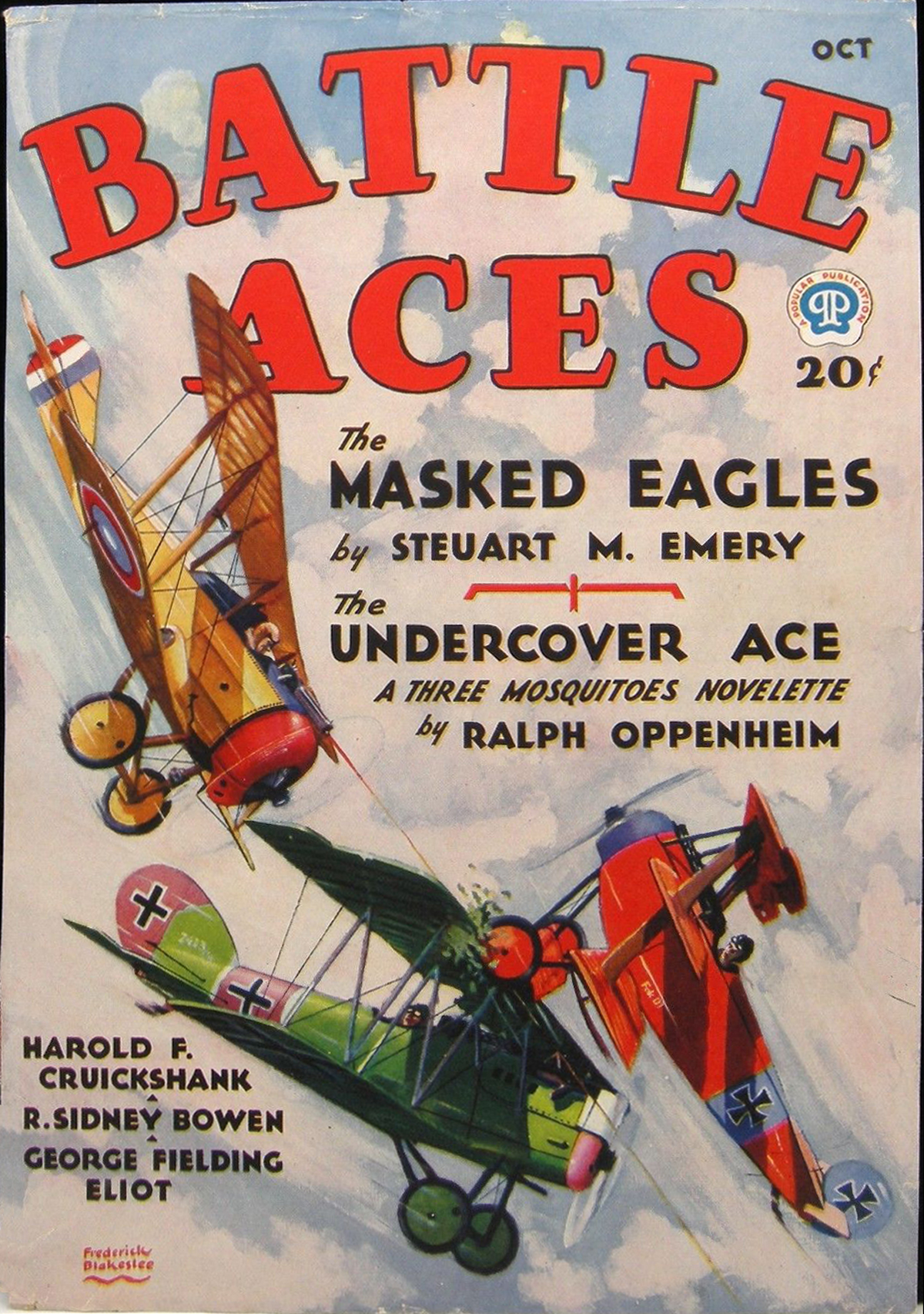

“Lt. Carr and the De H-5″ by Frederick Blakeslee

Editor’s Note: This month’s cover is the eleventh of the actual war-combat pictures which Mr. Blakeslee, well-known artist and authority on aircraft, is painting exclusively for BATTLE ACES. The scries was started to give our readers authentic pictures of war planes in color. It also enables you to follow famous airmen on many of their amazing adventures and feel the same thrills of battle they felt.

IN JUNE, 1918, there arrived at a certain American airdrome in France a group of replacements who had been trained in England. Among them was a lad by the name of Carr. To use a remark of one of his instructors, he was “the world’s worst pilot but a damn fine lad.” He had wrecked more ships than any man in camp. Why he was not thrown out of aviation, or at best sent to an observation group, he did not know. The fact remains that in the final test he passed, and was sent with five others to a fighting squadron. This squadron was proud of its toughness and its record for victories. The squadron leader looked the replacements over critically and approved, for they were just the type he wanted.

IN JUNE, 1918, there arrived at a certain American airdrome in France a group of replacements who had been trained in England. Among them was a lad by the name of Carr. To use a remark of one of his instructors, he was “the world’s worst pilot but a damn fine lad.” He had wrecked more ships than any man in camp. Why he was not thrown out of aviation, or at best sent to an observation group, he did not know. The fact remains that in the final test he passed, and was sent with five others to a fighting squadron. This squadron was proud of its toughness and its record for victories. The squadron leader looked the replacements over critically and approved, for they were just the type he wanted.

Carr was tall, with broad shoulders and an infectious smile—the sort of fellow one likes instantly. He was selected to be the first to go over the lines. Accordingly, next morning he was one of five to line up and take off. However, only four actually did take off. Carr’s ship went wobbling across the field and came up standing in a hedge. The mechanics looked it over for defects and, fortunately for Carr, found one that might have caused the crack-up. Carr, much surprised, thanked his lucky stars for that. Naturally he did not mention that the accident was due to his own stupidity. He was congratulated on his escape and wished better luck.

His next chance arrived and this time he managed to get into the air. His orders were strict; should a fight occur or if he were to loose the others, he was to return immediately. He was back in ten minutes—the time it took him to get lost and return to the airdrome. It did not help his reputation when he crashed in landing.

There followed a painful series of mishaps by which he became known as the “lovable ole dub.” It took them less than a week to discover that Carr would make a far better cab driver than a pilot. On the other hand he was the leader of all their binges. His smile carried him through all his troubles and with the willing help of the rest of the squadron his mistakes were smoothed over. However he was a great responsibility to flight leaders, who dreaded to have him in their patrol. At last, after a bit of particularly stupid flying, the C. O. decided that he would have to return to England. Carr was broken-hearted; he would rather die than be sent back. Rage against his own inability to fly determined him to try one last flight on which he would cither kill or be killed.

Early on the day he was to leave he took out his ship, gave it the gun and swept into the air. Although he did not realize it at the time, he was flying as he should have flown long ago. For the first time, instead of putting his ship into the air by sheer nervous will power, he forgot flying and thought only of fighting.

He had not gone far when he saw a patrol of Jerries beneath him. Without an instant’s hesitation he dove with such fury that he scattered the German ships right and left. Before they had become organized, he had shot down two of them. He dove head-on at another, intending to crash and end his life; but the panic-stricken Boche pulled up and fled with the others who had had enough of this mad American. Carr turned his De H-5 about just in time to see a green Pfalz diving at him. He plunged at him head-on, ripping out a savage burst. The Jerry, badly hit, looped but Carr looped after him.

Just at this point a Fokker Tripe joined the fight. Both planes came out of the loop with Carr on the German’s tail and his tracers crashing into the ship ahead. The Fokker zoomed and his wheel smashed through the left wing of the Pfalz, which went down out of control and crashed behind our lines. In a moment the pilot of the Fokker discovered that he had made a mistake in thinking that he or anyone could withstand such reckless and savage fury. He gave up in panic, raised his hands in token of surrender and followed Carr meekly back.

Carr returned to an overjoyed squadron, as confirmation of his victories had traveled ahead. He did not return to England. Instead he rose to be flight leader, then C.O., and finally became one of America’s aces.

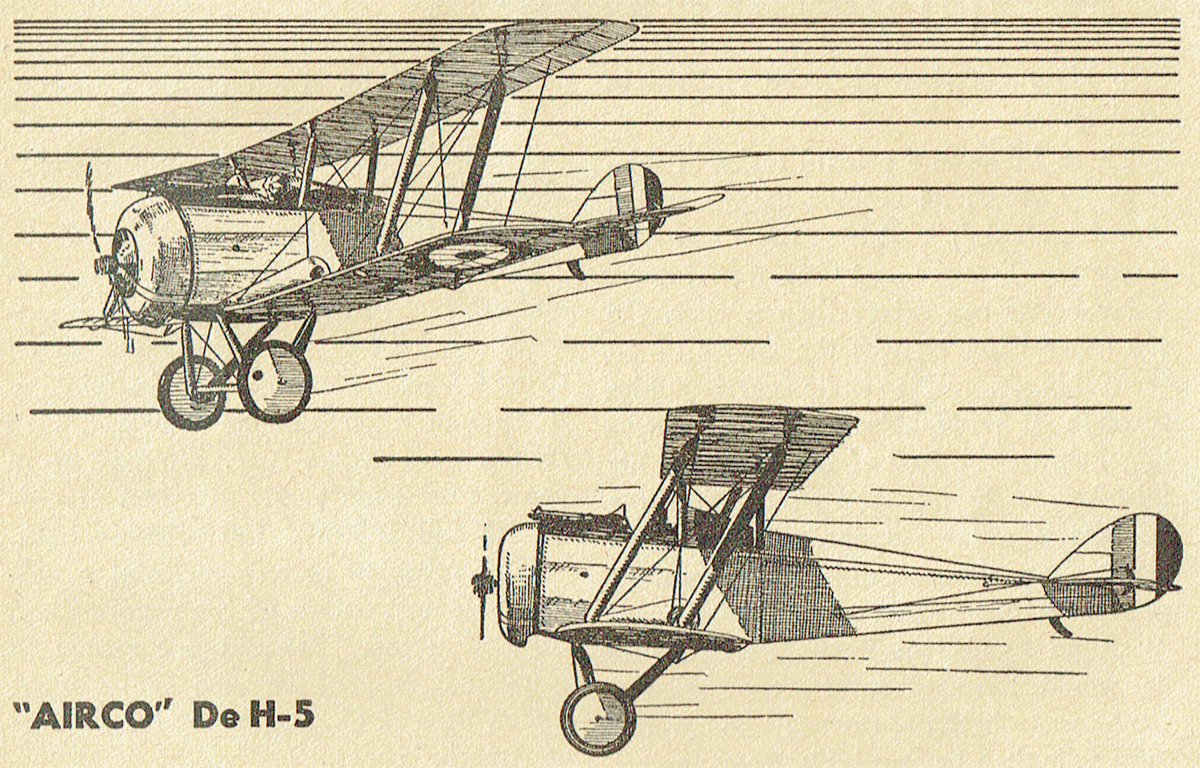

The De H-5 was produced late in 1916 and was extensively used at the front. It was so constructed that the pilot’s view upward and foreward was not entirely blanketed by the top wing. For this reason the top wing was staggered backward and the pilot’s cockpit put beneath the leading edge of that wing. Despite loss of efficiency which resulted from this backward stagger, by careful attention to the reduction of head resistance, a ship was produced with very good all-round performance. Its span was 25′-8″; length 22′; engine 110 h.p., Le Rhone; speed at 10,000 ft. 102 m.p.h.; landing speed 50 m.p.h.; approximate ceiling 15,000 ft.

“Lt. Carr and the De H-5″ by Frederick M. Blakeslee (October 1932)