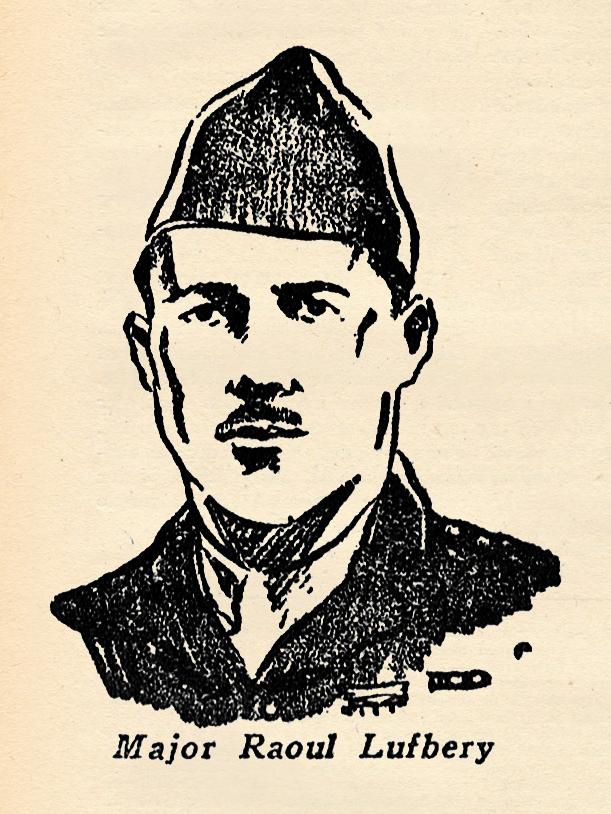

My Most Thrilling Sky Fight: Major Raoul Lufbery

Amidst all the great pulp thrills and features in Sky Fighters, they ran a true story feature collected by Ace Williams wherein famous War Aces would tell actual true accounts of thrilling moments in their fighting lives! This time it’s the inimitable Major Raoul Lufbery’s Most Thrilling Sky Fight!

Raoul Lufbery was  already famous when America entered the War. For some time he was the mechanic of Marc Pourpe, famous French flyer. Pourpe was killed in aerial combat. Lufbery who was with the Foreign Legion, asked to take his place in order to avenge his death. The French army, defying usual procedure sent him to join Escadrille de Bombardmente V. 102, where he made a distinguished record.

already famous when America entered the War. For some time he was the mechanic of Marc Pourpe, famous French flyer. Pourpe was killed in aerial combat. Lufbery who was with the Foreign Legion, asked to take his place in order to avenge his death. The French army, defying usual procedure sent him to join Escadrille de Bombardmente V. 102, where he made a distinguished record.

When the La Fayette Escadrille was formed, he became one of the seven original members of that famous air squadron—and, as it proved ultimately, became the most distinguished, winning his commission as a sous-lieutenant.

When America entered the War he was transferred to the American Air Service and made a major, refusing, however, to take command of a squadron. When he was killed at Toul. Lufbery was officially credited with 17 victories. The story below was told to a Chicago newspaper correspondent a few days before his death at Toul airdrome

THREE AVIATIKS (?) WITH ONE SHOT

by Major Raoul Lufbery • Sky Fighters, December 1933

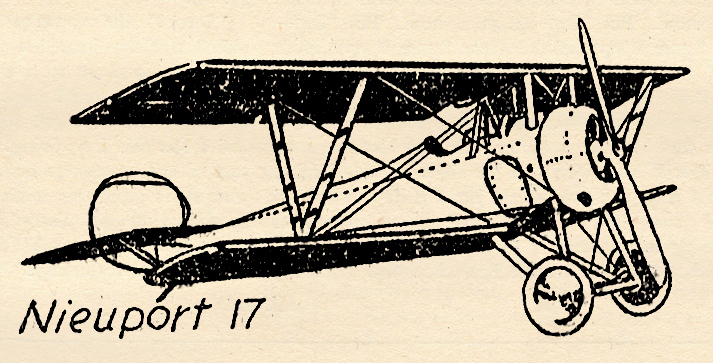

YOU ASK me my most memorable flight? Let me think a minute. Ah, I have it! It was the day at Luxeuil soon after we got our new Nieuports, the day the great air armada bombed Karlsruhe on the Rhine.

With Prince, De Laage, Masson, I took off from the drome at Luxeuil. We climbed all the time. Below us was the formation of French and British bombers we were to escort. Above were great masses of clouds. We went up through them, looking for Boche on top. But, there were none. That is, I saw none, but I felt that I was being watched.

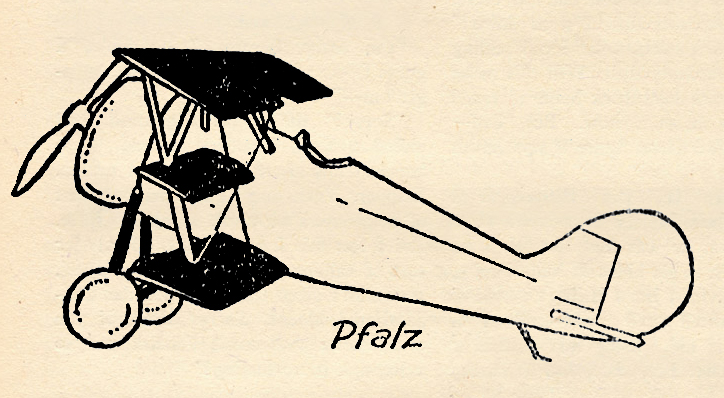

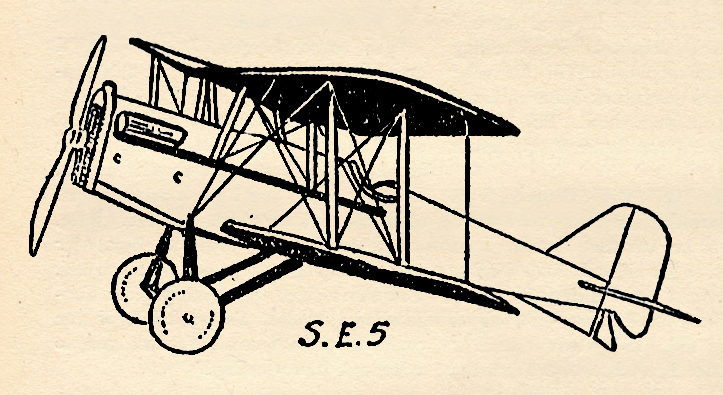

I glanced up suddenly. Just in time! A three-seater Aviatik was diving on me. My companions had gone ahead. I turned back quickly, making believe I had not seen the Aviatik. I wanted the pilot to come closer before I started shooting.

The Boche tracer screamed over my head. I moved the stick, sent my Nieuport into a screeching chandelle. The black Aviatik whirled past me, tracer streams spouting like fountains. I straightened out, my fingers going tight on the gun trips. I dived, got the Aviatik in range, let go with a long burst while I feathered the controls, making my tracer stream weave. But the Boche pilot was no amateur. He slipped away.

His bullets shattered my compass. The alcohol in the bowl spurted, clouding my goggle glasses. I shoved them up on my forehead. The alcohol sprayed in my eyes, burned. I blinked. All I could see was red. I was blind! But I heard the Boche tracer ripping through my wings. I dived, then maneuvered crazily. I shook my head, threw off one mitten, wiped my eyes with the back of my hand. All the time I was weaving my stick, diving and zooming alternately, to give an erratic target. My eyes began to clear and I looked out overside.

I saw three Aviatiks then. All black, all shooting at me. I maneuvered some more, managed to get my guns lined on one of them. I pressed the gun trips quickly. My tracer streamed out in a blue haze. All three Aviatiks tumbled over in the sky and fell down at once. I banked, went circling after them to see that they crashed. It was only when I was almost to the ground, that I saw it was only one Aviatik that had crashed.

My eyes, blurred by compass alcohol, had tricked me. There was only one Aviatik where I had seen three. I got only one when I thought I had three. But I was happy enough,

anyway.

That one Aviatik might have got me if—I had not been so lucky.

Donald McLaren was born in Ottawa, Canada, in 1893, but at an early age his parents moved to the Canadian Northwest, where he grew up with a gun in his hands. He got his first rifle at the age of six, and was an expert marksman by the time he was twelve. When the war broke out he was engaged in the fur business with his father, far up in the Peace River country. He came down from the north in the early spring of 1917 and enlisted in the Canadian army, in the aviation section. He went into training at Camp Borden, won his wings easily and quickly, and was immediately sent overseas. In February, 1918, he downed his first enemy aircraft. In the next 9 months he shot down 48 enemy planes and 6 balloons, ranking fourth among the Canadian Aces and sixth among the British. No ranking ace in any army shot down as many enemy aircraft as he did in the same length of time. For his feats he was decorated with the D.S.O., M.C., D.F.C. medals of the British forces, and the French conferred upon him both the Legion d’Honneur and Croix de Guerre. Oddly, just before the war ended, he was injured in a wrestling match with one of his comrades and spent armistice day in a hospital nursing a broken leg. He had gone through over a hundred air engagements without receiving a scratch. The air battle he describes below is unusual because almost 100 planes took part in it.

Donald McLaren was born in Ottawa, Canada, in 1893, but at an early age his parents moved to the Canadian Northwest, where he grew up with a gun in his hands. He got his first rifle at the age of six, and was an expert marksman by the time he was twelve. When the war broke out he was engaged in the fur business with his father, far up in the Peace River country. He came down from the north in the early spring of 1917 and enlisted in the Canadian army, in the aviation section. He went into training at Camp Borden, won his wings easily and quickly, and was immediately sent overseas. In February, 1918, he downed his first enemy aircraft. In the next 9 months he shot down 48 enemy planes and 6 balloons, ranking fourth among the Canadian Aces and sixth among the British. No ranking ace in any army shot down as many enemy aircraft as he did in the same length of time. For his feats he was decorated with the D.S.O., M.C., D.F.C. medals of the British forces, and the French conferred upon him both the Legion d’Honneur and Croix de Guerre. Oddly, just before the war ended, he was injured in a wrestling match with one of his comrades and spent armistice day in a hospital nursing a broken leg. He had gone through over a hundred air engagements without receiving a scratch. The air battle he describes below is unusual because almost 100 planes took part in it.

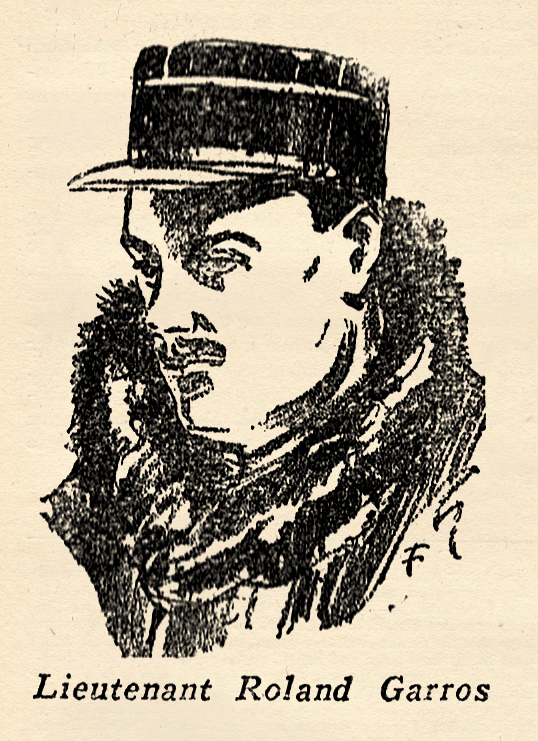

one of the world’s foremost airmen before the World War began. When the French army was mobilized, Garros joined his squadron, the Morane-Saulnier 23, just as it was leaving for the front. He built up a wonderful record for himself in respect to scouting.

one of the world’s foremost airmen before the World War began. When the French army was mobilized, Garros joined his squadron, the Morane-Saulnier 23, just as it was leaving for the front. He built up a wonderful record for himself in respect to scouting.

we have a tale from the anonymous pen of Lt. Frank Johnson—a house pseudonym. Sky Fighters ran a series of stories by Johnson featuring a pilot who who was God’s gift to the Ninth Pursuit Fighter Squadron and although he says he’s a doer and not a talker, he wasn’t to shy to tell them all about it. Which earned him the nickname “Silent” Orth.

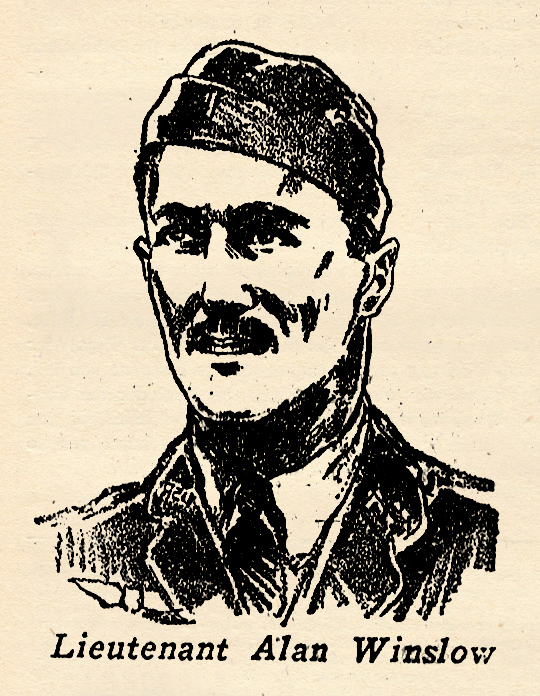

we have a tale from the anonymous pen of Lt. Frank Johnson—a house pseudonym. Sky Fighters ran a series of stories by Johnson featuring a pilot who who was God’s gift to the Ninth Pursuit Fighter Squadron and although he says he’s a doer and not a talker, he wasn’t to shy to tell them all about it. Which earned him the nickname “Silent” Orth.  went oyer to France as a member of tho American Ambulance Section serving with the French Army. After America entered the war he was transferred to the American Army. When the American Air Service under command of Colonel Mitchell began definite duties on the Western Front, Alan Winslow had won his commission as a First Lieutenant and was assigned as a pilot in the 94th Aero Squadron, the famous “Hat in the Ring” outfit later made famous by Captain Eddie Rickenbacker.

went oyer to France as a member of tho American Ambulance Section serving with the French Army. After America entered the war he was transferred to the American Army. When the American Air Service under command of Colonel Mitchell began definite duties on the Western Front, Alan Winslow had won his commission as a First Lieutenant and was assigned as a pilot in the 94th Aero Squadron, the famous “Hat in the Ring” outfit later made famous by Captain Eddie Rickenbacker.

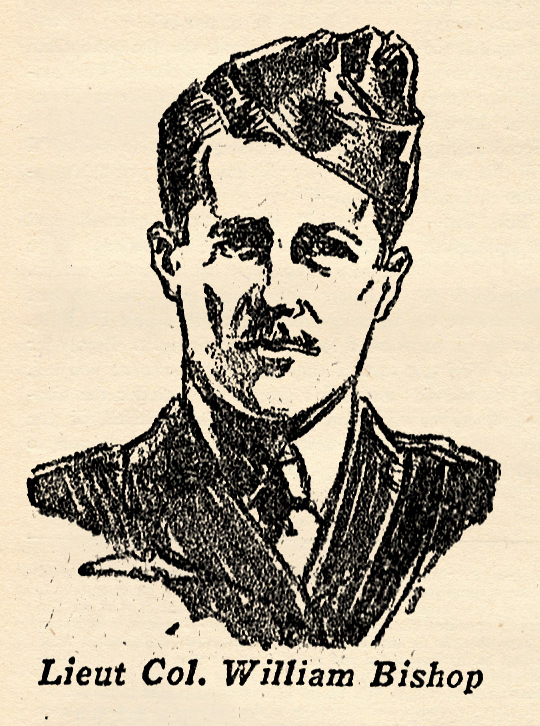

is one of the few great war Aces still living. And he probably owes his life to the fact that the British General Staff ordered him to Instruction duty in London while the war was still on. Bishop first served in the Second Canadian Army as an officer of cavalry, but tiring of the continuous Flanders mud, he made application for transfer to the Royal Flying Corps. He was first sent up front as an observer. When he went up later as a pilot he immediately began to compile the record which established him as the British Ace of Aces. He won every honor and medal possible. He was an excellent flyer, but attributed most of his success to his wizardry with the machine-gun. When the war ended he was officially credited with downing 72 enemy planes and balloons. The account below is from material he gathered for a book.

is one of the few great war Aces still living. And he probably owes his life to the fact that the British General Staff ordered him to Instruction duty in London while the war was still on. Bishop first served in the Second Canadian Army as an officer of cavalry, but tiring of the continuous Flanders mud, he made application for transfer to the Royal Flying Corps. He was first sent up front as an observer. When he went up later as a pilot he immediately began to compile the record which established him as the British Ace of Aces. He won every honor and medal possible. He was an excellent flyer, but attributed most of his success to his wizardry with the machine-gun. When the war ended he was officially credited with downing 72 enemy planes and balloons. The account below is from material he gathered for a book.

was the greatest of all the German flyers. He had more victories to his credit than any other battle flyer. He began in the Imperial Flying Corps, on the Russian Front. Soon afterwards he was transferred to the German North Seas station at Ostend, where he served as a bomber. Backseat flying never appealed to him, so he took training, soon won his wings, and was sent to join the jagdstaffel commanded by Oswald Boelke. After his sixteenth victory, he was promoted to Lieutenant and assigned to command a squadron. This became the Flying Circus, the most famous of all the German squadrons, the scourge of the western skies.

was the greatest of all the German flyers. He had more victories to his credit than any other battle flyer. He began in the Imperial Flying Corps, on the Russian Front. Soon afterwards he was transferred to the German North Seas station at Ostend, where he served as a bomber. Backseat flying never appealed to him, so he took training, soon won his wings, and was sent to join the jagdstaffel commanded by Oswald Boelke. After his sixteenth victory, he was promoted to Lieutenant and assigned to command a squadron. This became the Flying Circus, the most famous of all the German squadrons, the scourge of the western skies.

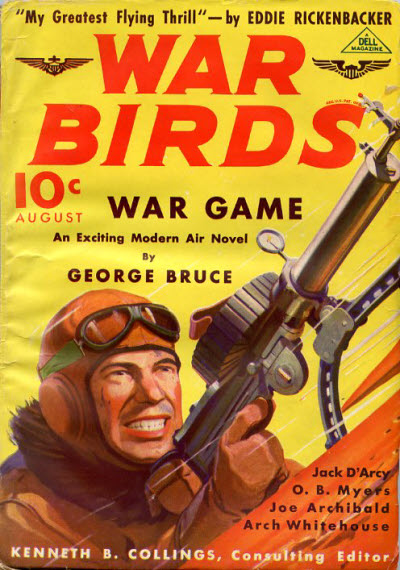

as a bonus, Joe Archibald’s first tale of Ambrose Hooley. No Muley Spinks as yet, but all the other elements are there—the 93 Pursuit Squadron, Major Bagby and Ambrose shooting krauts out of the sky like ducks in a barrel while simultaneously working all the angles. The tale of assumed identity is illustrated by our old friend

as a bonus, Joe Archibald’s first tale of Ambrose Hooley. No Muley Spinks as yet, but all the other elements are there—the 93 Pursuit Squadron, Major Bagby and Ambrose shooting krauts out of the sky like ducks in a barrel while simultaneously working all the angles. The tale of assumed identity is illustrated by our old friend