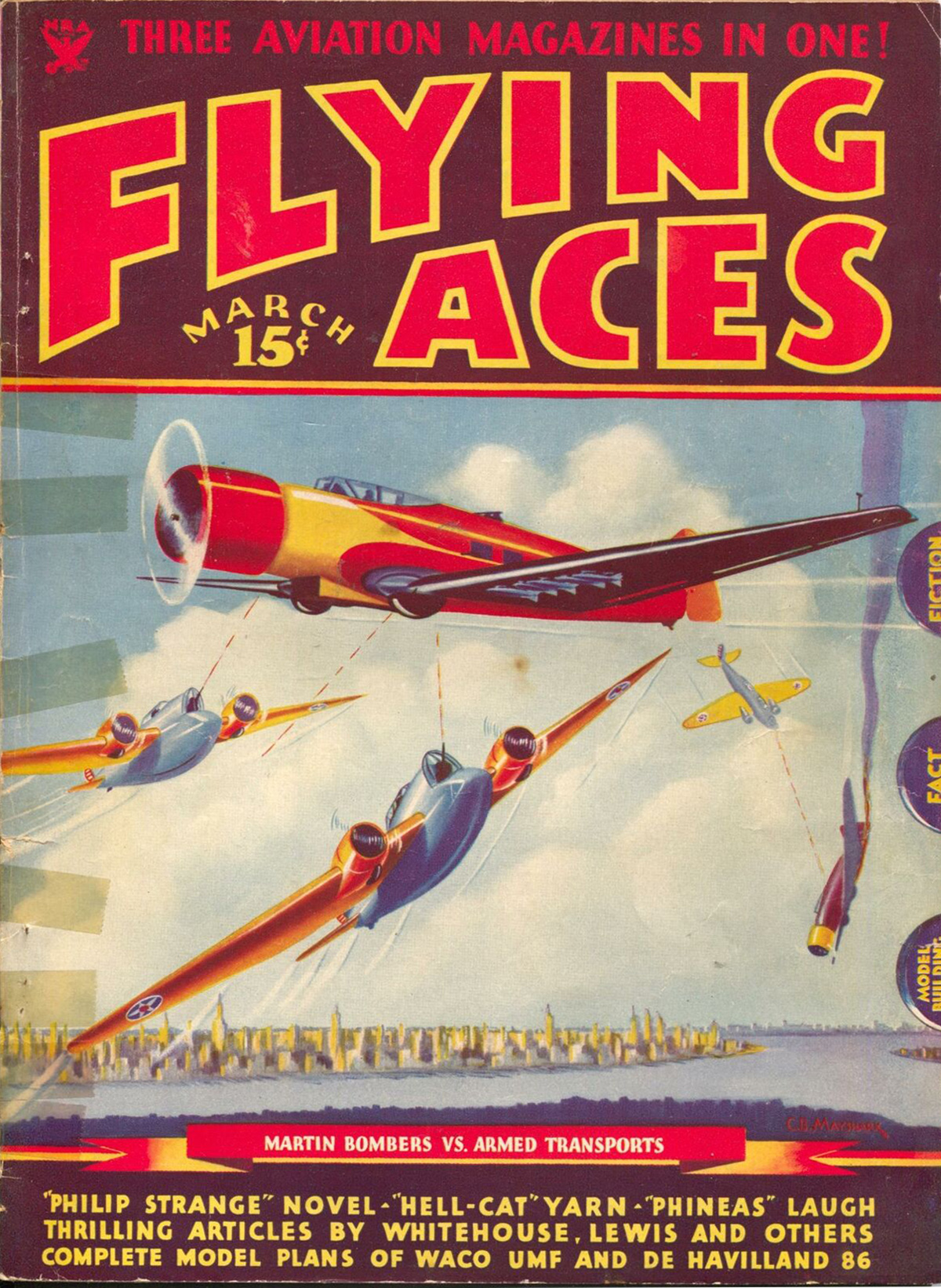

“Flying Aces, March 1935″ by C.B. Mayshark

THIS May we are once again celebrating the genius that is C.B. Mayshark! Mayshark took over the covers duties on Flying Aces from Paul Bissell with the December 1934 issue and would continue to provide covers for the next year and a half until the June 1936 issue. While Bissell’s covers were frequently depictions of great moments in combat aviation from the Great War, Mayshark’s covers were often depictions of future aviation battles and planes. March 1935’s thrilling story behind its cover features Martin Bombers vs. Armed Transports!

Martin Bombers vs. Armed Transports

NEW YORK, the metropolis of the nation, threatened with complete ruin! An unknown foe striking from the mist-shrouded deeps of the North Atlantic on wings of treachery, with all the speed of light and the blasting power of lightning! High-speed bombers converted in a few hours from peaceful commercial craft, loaded with high explosive and bristling with machine guns!

NEW YORK, the metropolis of the nation, threatened with complete ruin! An unknown foe striking from the mist-shrouded deeps of the North Atlantic on wings of treachery, with all the speed of light and the blasting power of lightning! High-speed bombers converted in a few hours from peaceful commercial craft, loaded with high explosive and bristling with machine guns!

A wild fantasy? Impossible? But not so! Already it has been proved that several well-known commercial types used by many countries are so constructed that within a few hours they may be turned into grim war craft.

Any day, the great city of New York might be shining in the sunlight of a Spring morning to realize suddenly that within an hour the sunshine was to be blotted out by clouds of poison gas, billowing waves of screen smoke and the acrid fumes of high-explosive flame. Great buildings might be blasted from their bases, to topple with the thunder of Thor down into the cavernous streets of the city, wiping out hundreds of lives and spreading destruction in their crunching wake. Death and disease would stalk through the ruins and blot out thousands. Famine, waste and thirst would follow the concussion as these aerial monsters screened behind peaceful commercial insignia swooped down and struck the first blow of an unexpected war.

But their mission might be detected by the roving Coast Guardsmen, and great Martin bombers would sweep into the sky to intercept them. The Junkers Ju. 60 depicted on this month’s cover is a typical ship on which this conversion job could be attempted. And remember, Germany is not the only foreign power that uses this type of commercial craft. The Junkers ships are manufactured under license all over the world, so the Ju. 60 could be the vanguard of attack from any one of several foreign countries.

The Ju. 60 is classified as an express monoplane. It will accommodate eight persons, a more than adequate number for a bombing crew. The only visible changes in the ship are the gunner’s door in the roof, the bomb equipment, including racks and bombs under the wings, and the machine guns protruding from the side windows. Of course, other minor changes would be necessary within the fuselage.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of this ship is its power plant. The engine is a B.M.W. Hornet, and it is built in Germany under license from the Pratt & Whitney Co. of Hartford, Conn. Its design is absolutely identical with the Hornet series A of the licensor. The Hornet is a nine-cylinder, air-cooled radial engine on detachable engine mounting, and it is capable of 600 horsepower. A three-bladed metal air screw is used.

The ship can attain a speed of 175 miles per hour and has a range of 683 miles. Undoubtedly, however, this range would be greatly increased when the bomber conversion job was completed.

The Martin bomber has received a great deal of publicity, which it has rightfully deserved. The performance of the Martins that made the Alaska trip last summer was indeed enviable. It is the general consensus of opinion that the Martin bombers of the YB series are the fastest and the most efficient ships of their type in the world. These ships do better than 200 miles per hour, and they are so maneuverable that they can be used as pursuit or attack planes in case of emergency.

Presuming that the United States is attacked by an unknown foreign power with an air arm that incorporates a number of these converted commercial ships, let us see what would be the result of an air battle between a Junkers and a modern Martin. We must, of course, take the fictional attitude that a fleet of these Junkers has been catapulted from a giant launching gear, or from the hurriedly converted flight deck of a long tanker, for a secret raid on some important military point on the mainland.

In the matter of a ship-to-ship conflict—that is to say, an equal number of Martins against a formation of Junkers—we must consider the duties of each ship. The Martins are on the defensive, purely and simply, while the raiding Junkers have the problem of making their bombing attack and defending themselves at the same time. After all that is over, they must get back to their surface base.

So far, so good. The Junkers have almost reached the mainland when their move has been spotted and the defending squadrons are sent aloft. If, for instance, as is the case, they have decided on a raid on New York City, they would first have to brave the anti-aircraft fire from any of the several forts in the mouth of the Hudson. This, in itself, is no easy task, and several would probably, on the law of war averages, go down or fail to gain their objective.

The rest would have to make their way through a winged wall of 200-mile-an-hour Martins armed with high speed and high-calibre guns. The Junkers, gorged with heavy bombs, would not get up to their best speed, and all battle tactics would have to be thrown aside in their dash for their targets. The Martins, on the other hand, unhampered by pre-arranged plans, would have the benefit of freedom of action under a general leadership of a squadron leader in a flag-plane. While the Junkers ships plunged on, dead for their objective, depending mainly on their gunners, the Martins would be able to form angle attacks to harass the visitors.

Now, it is not exactly true that the fastest ship always wins a fight, especially where defensive ships try to intercept bombing machines. The last year of the World War proved that, and we shall have to accept the fact that in this great defense, many Martins would be destroyed. However, with the gunnery of the modern bomber-fighter, the air battle would become something of a mid-air battle-cruiser engagement in which speed, careful maneuvering and gunnery would win.

In this case, then, the slower Junkers bombers, confined to a direct line of flight—at least, until they have reached and bombed their objective—would be on the short end of the battle, for the speedy Martins would be able to use all their, fighting tactics. The gunnery must be considered on modern figures. No country in the world today is believed to have the aerial weapons that the United States boasts.

Therefore, the Junkers would come under another bitter blow. While the enemy got in the first thrust by surprise in the use of a converted transport ship, the side with equipment especially designed for defensive work would win in the end. The attacking party always loses more than the defending—an old war axiom—but in doing so, it actually accomplishes its end or goal.

Thus, on facts and figures, the Martin bomber should always be able to outdo the converted commercial ship.

Flying Aces, March 1935 by C.B. Mayshark

Martin Bombers vs. Armed Transports: Thrilling Story Behind This Month’s Cover

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

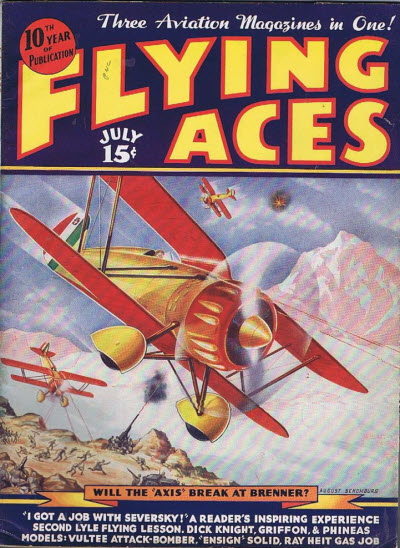

That sound can only mean one thing—it’s time to ring out the old year and ring in the new with that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors—Phineas Pinkham. The Boonetown miracle is misdirected to the wrong train in Paris coming back from leave and finds himself knee-deep in tulips and treachery! It’s a Dutch treat special—it’s Phineas in Holland! from the July 1938 issue of Flying Aces, it’s “Zuyder Zee Zooming!”

That sound can only mean one thing—it’s time to ring out the old year and ring in the new with that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors—Phineas Pinkham. The Boonetown miracle is misdirected to the wrong train in Paris coming back from leave and finds himself knee-deep in tulips and treachery! It’s a Dutch treat special—it’s Phineas in Holland! from the July 1938 issue of Flying Aces, it’s “Zuyder Zee Zooming!”

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

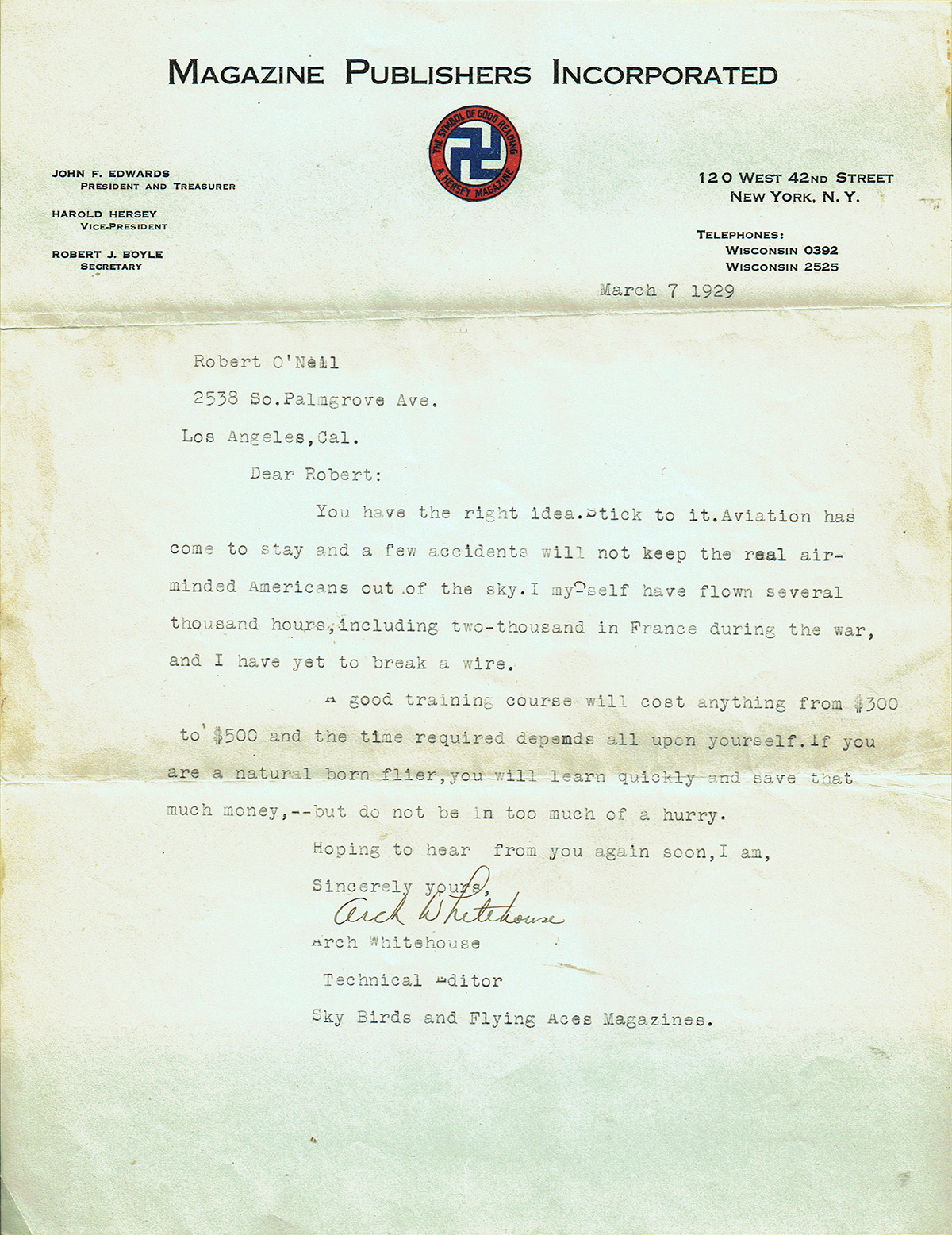

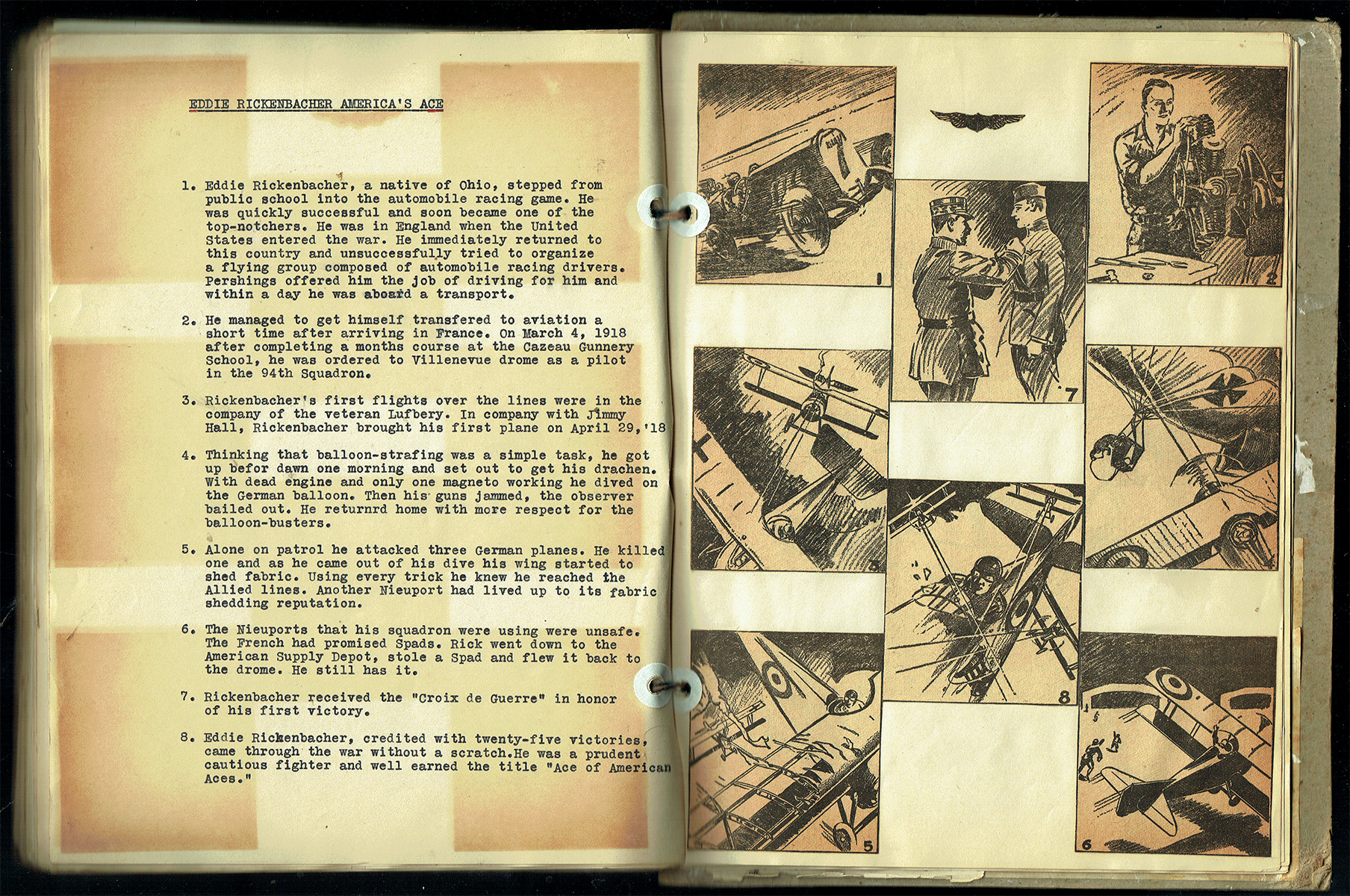

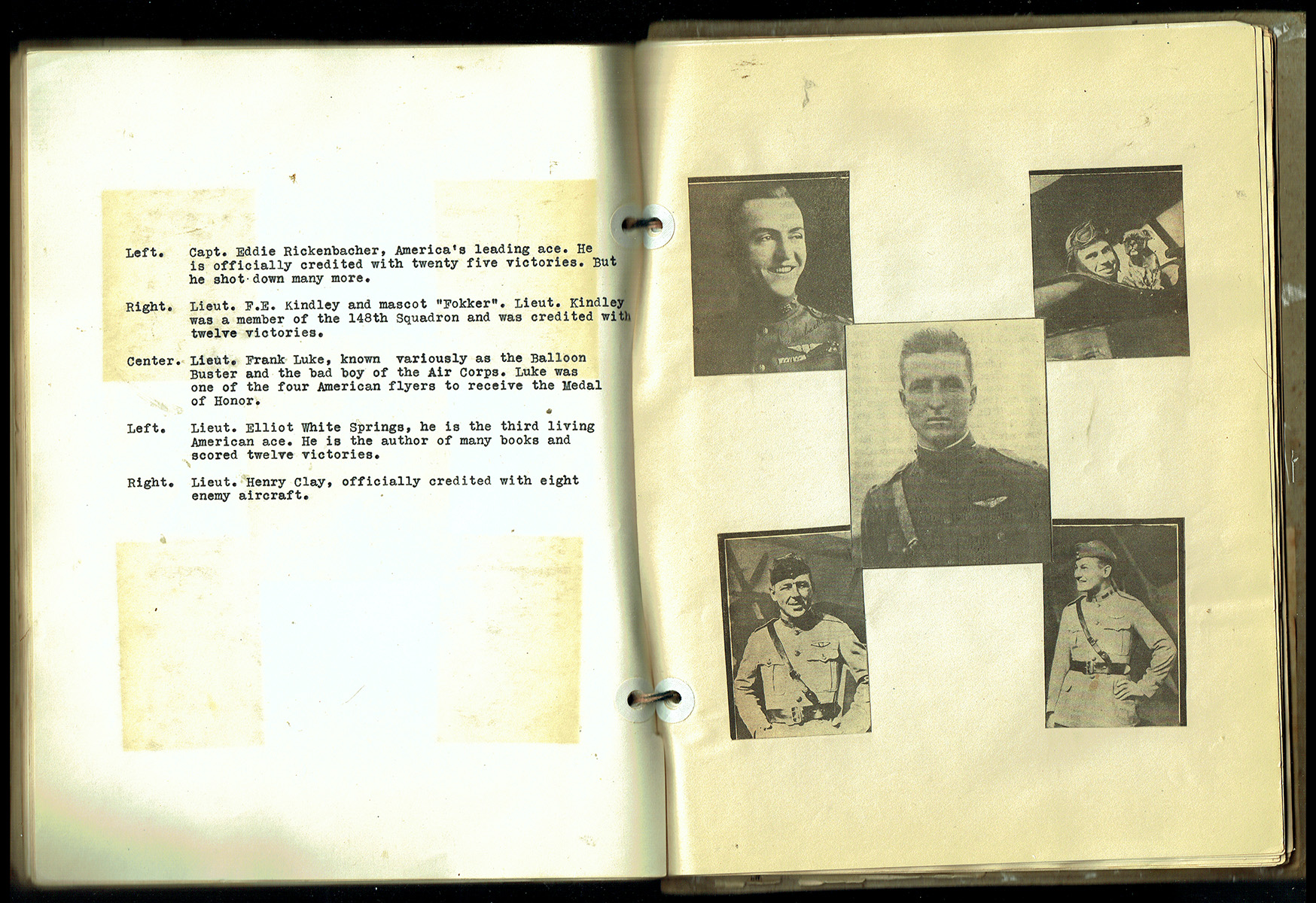

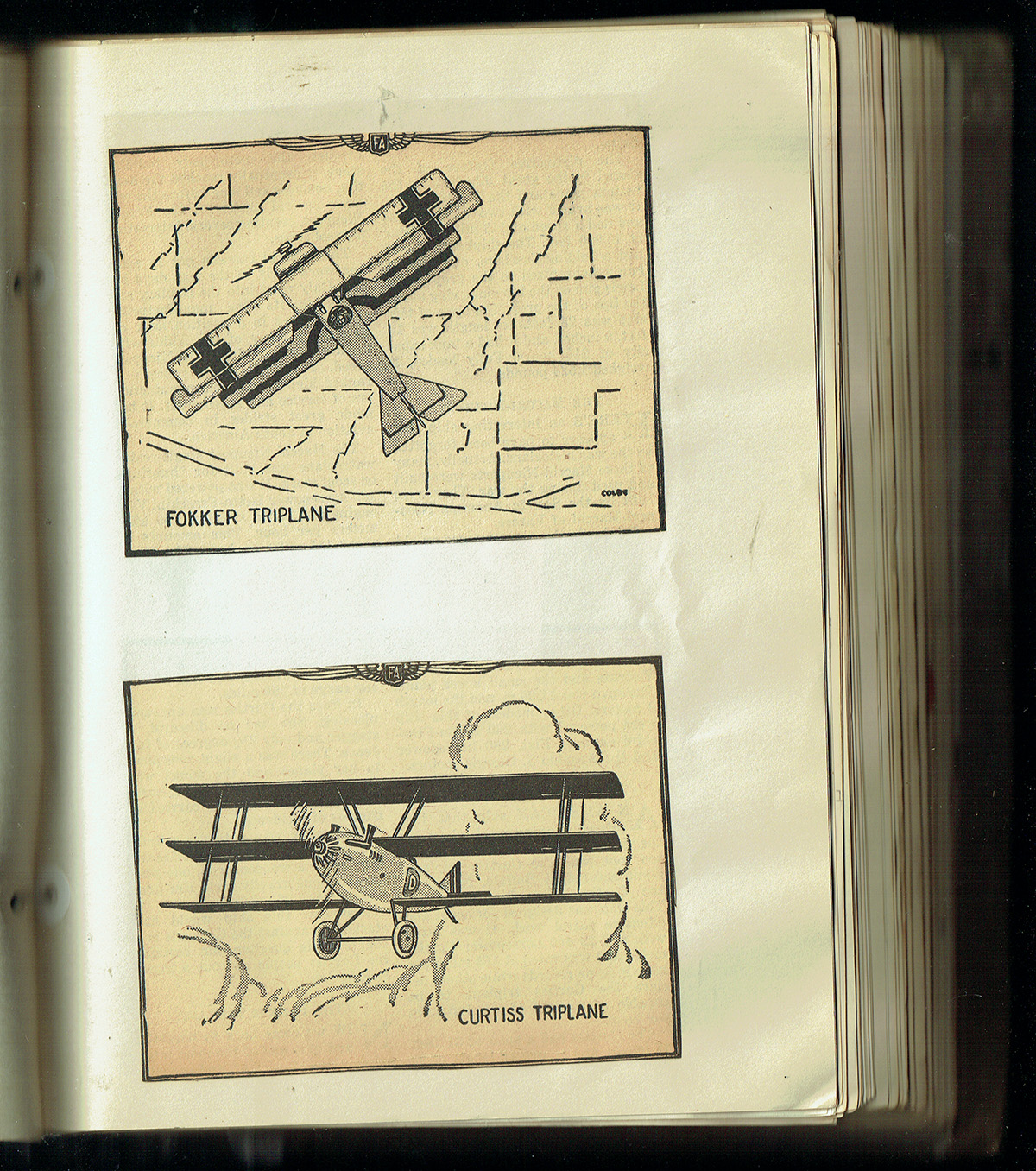

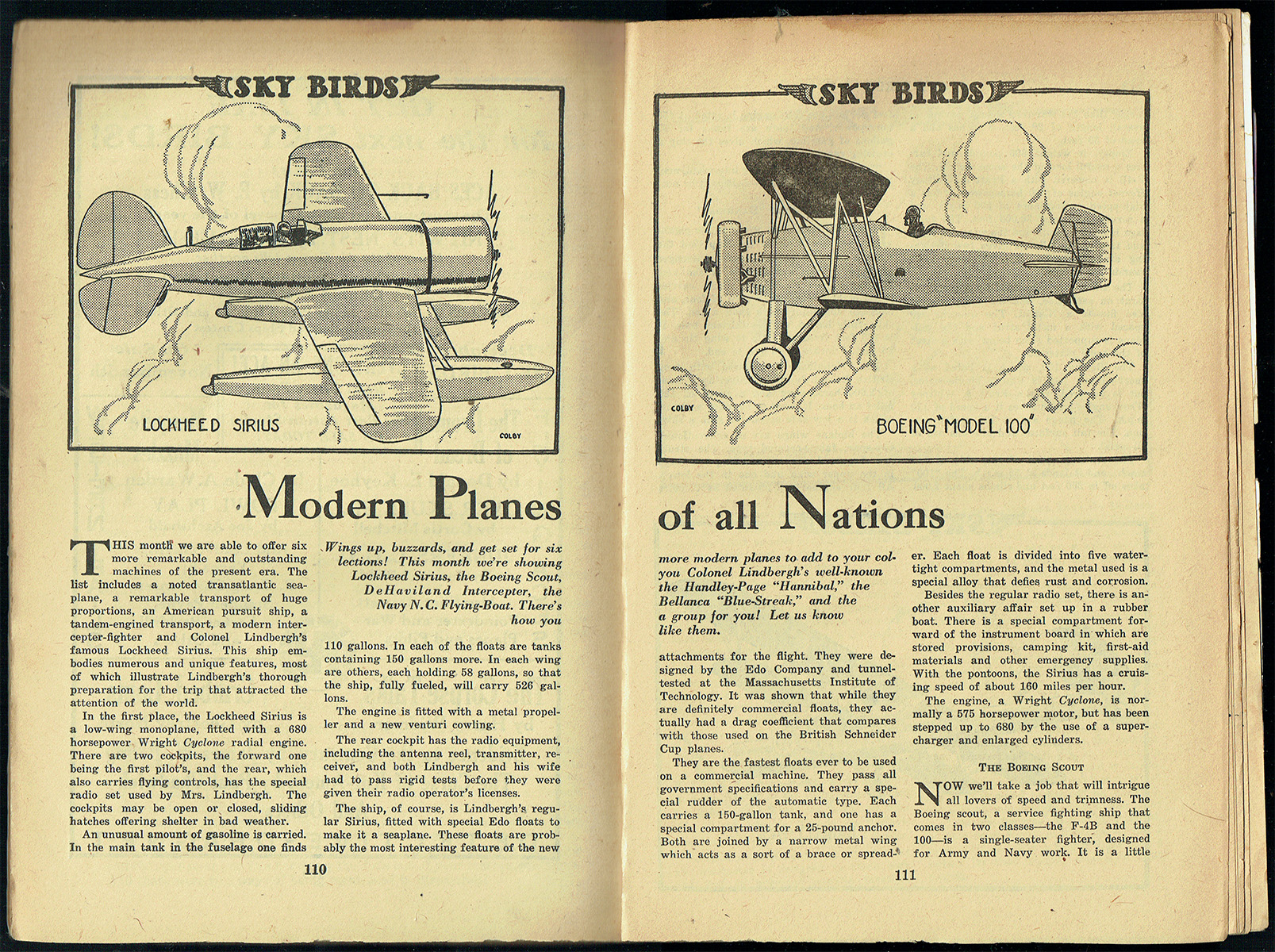

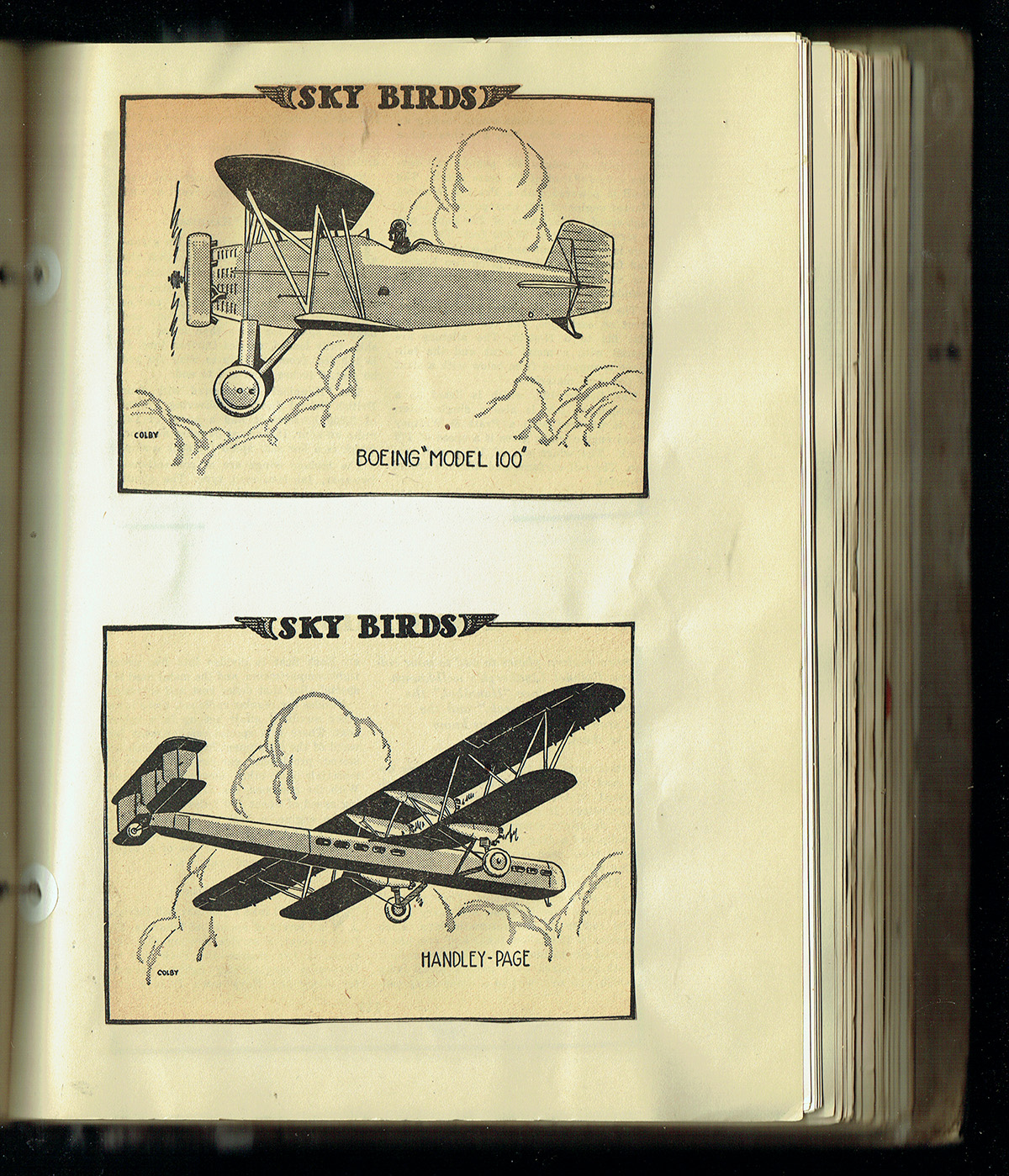

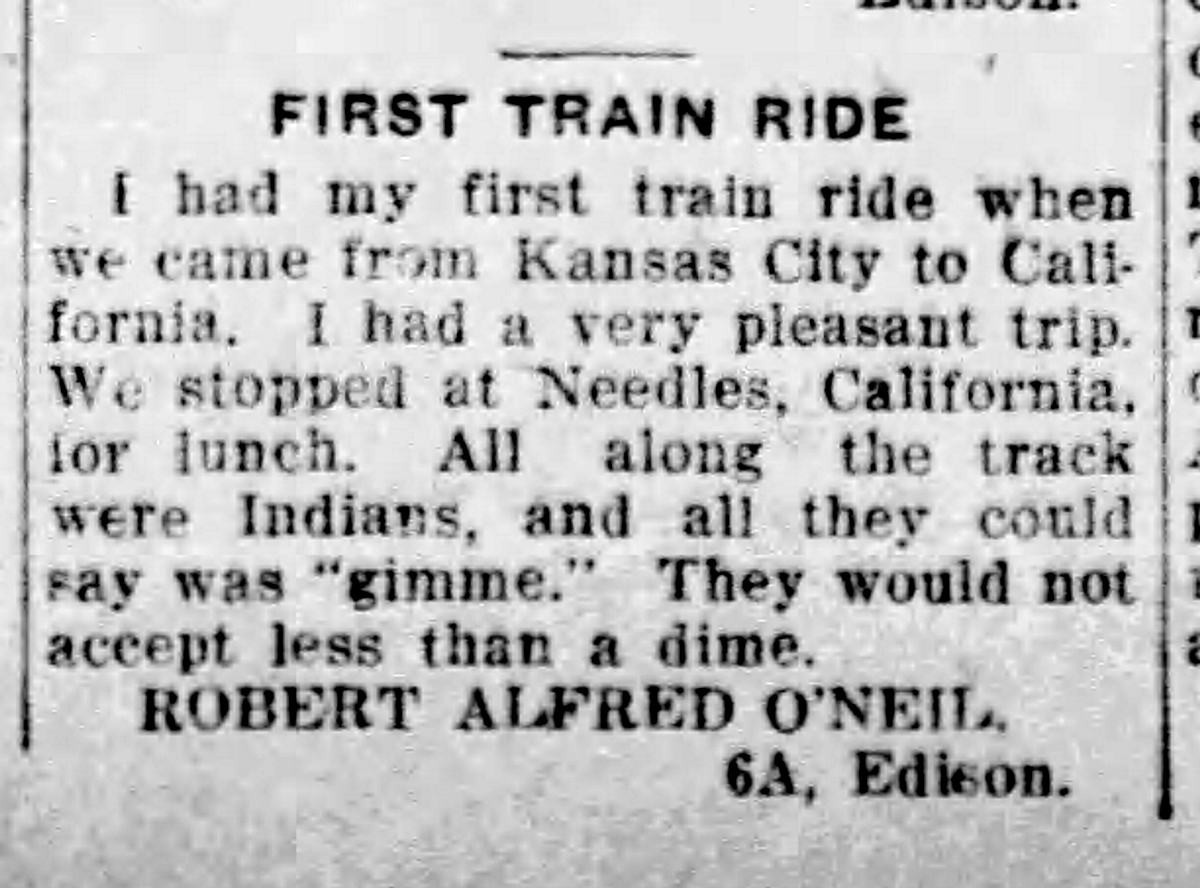

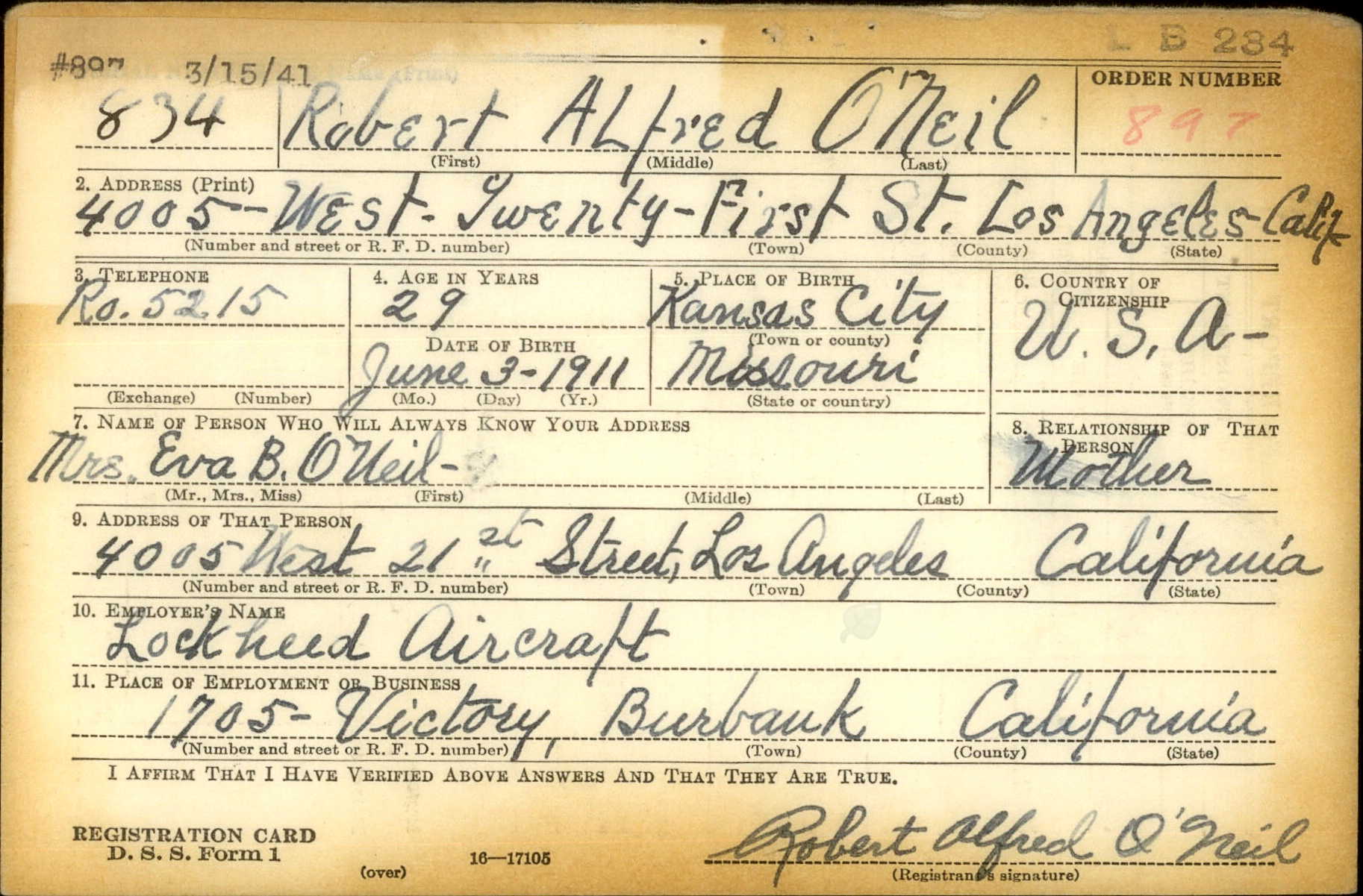

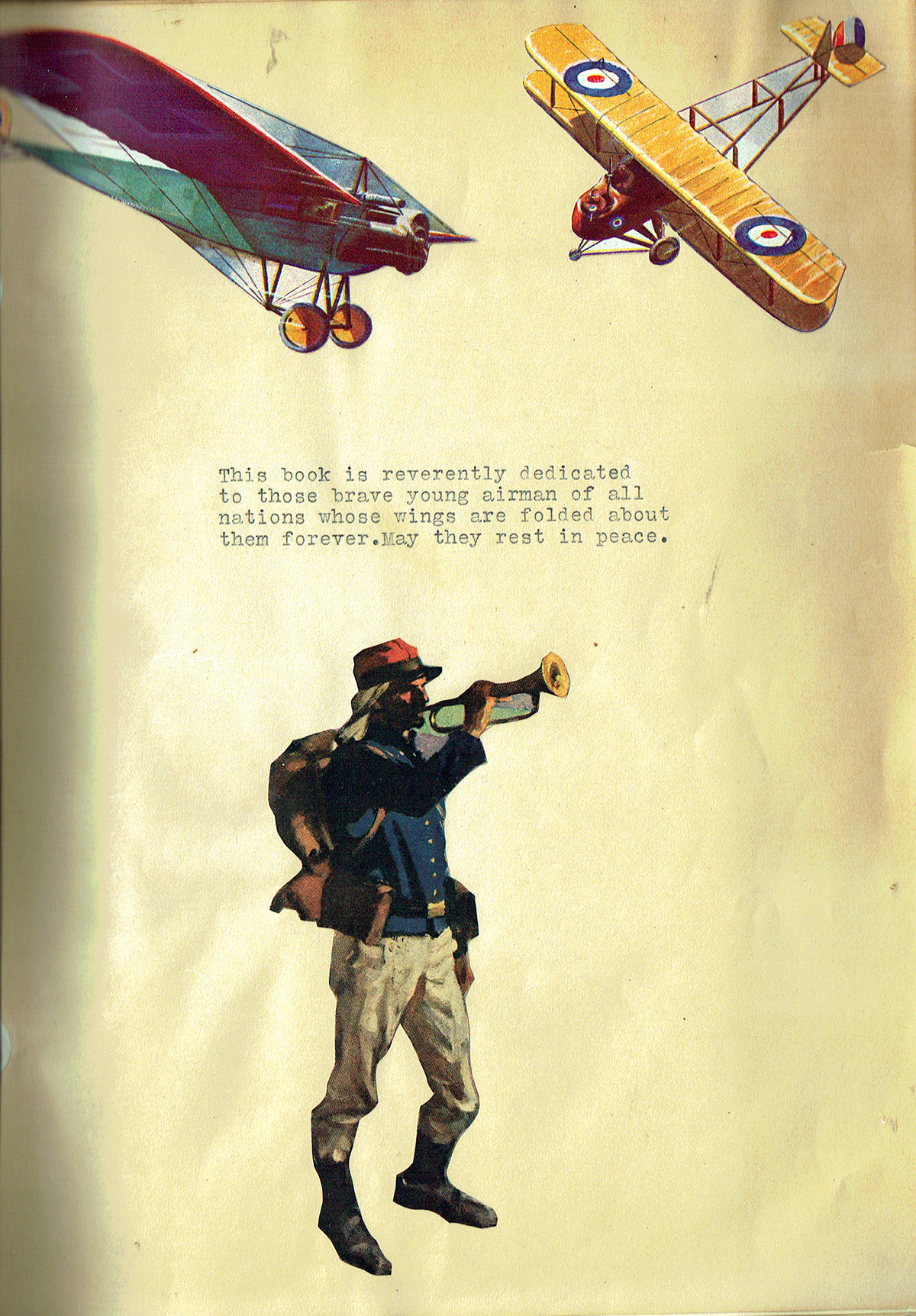

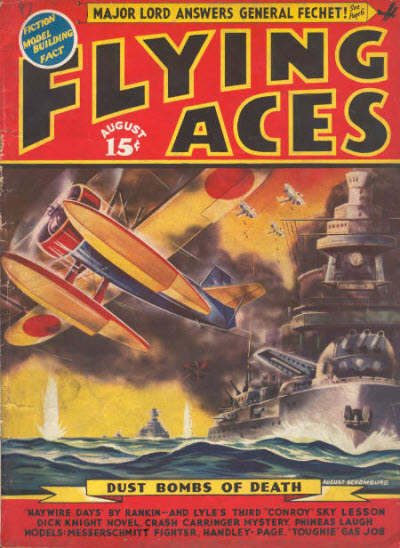

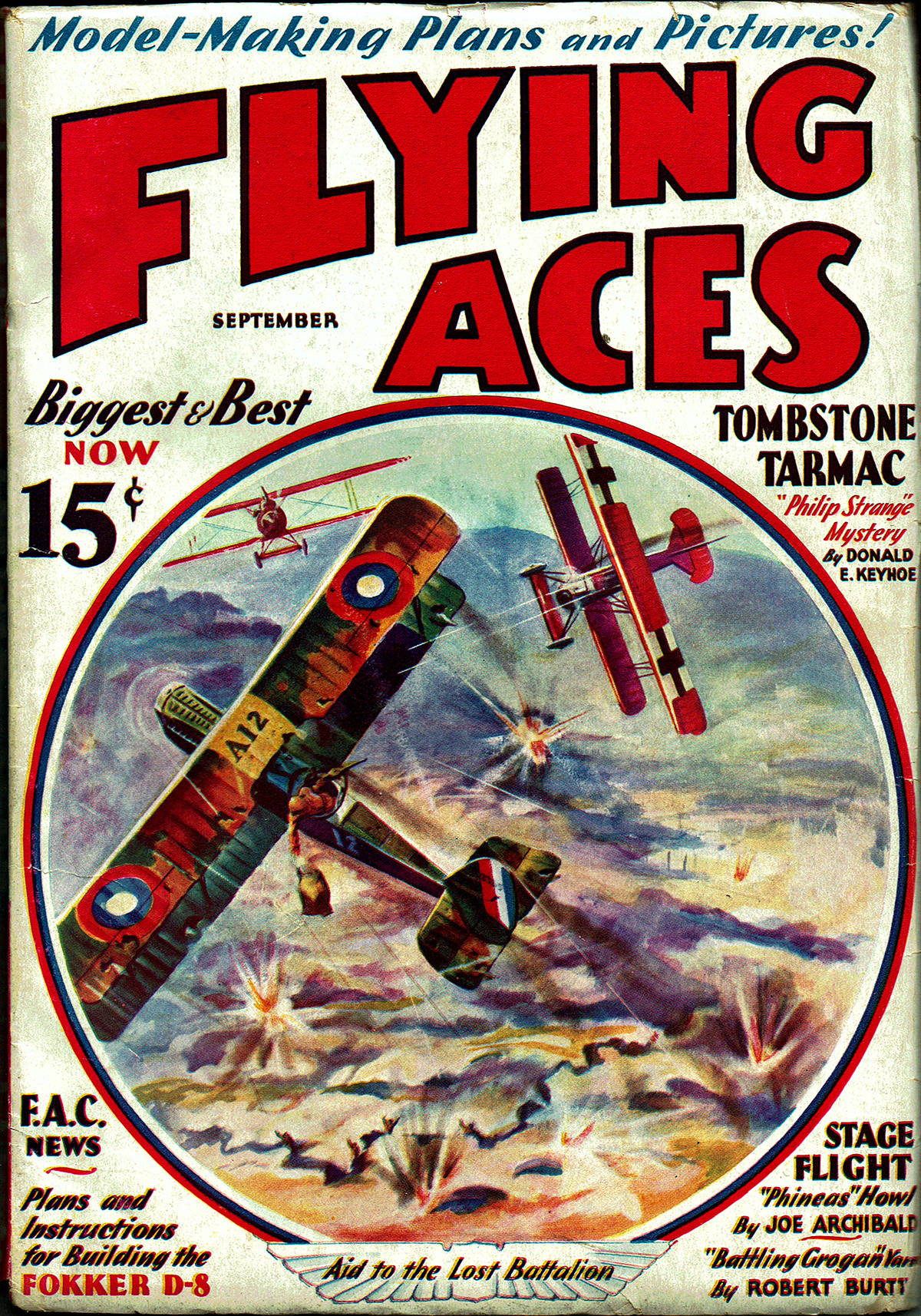

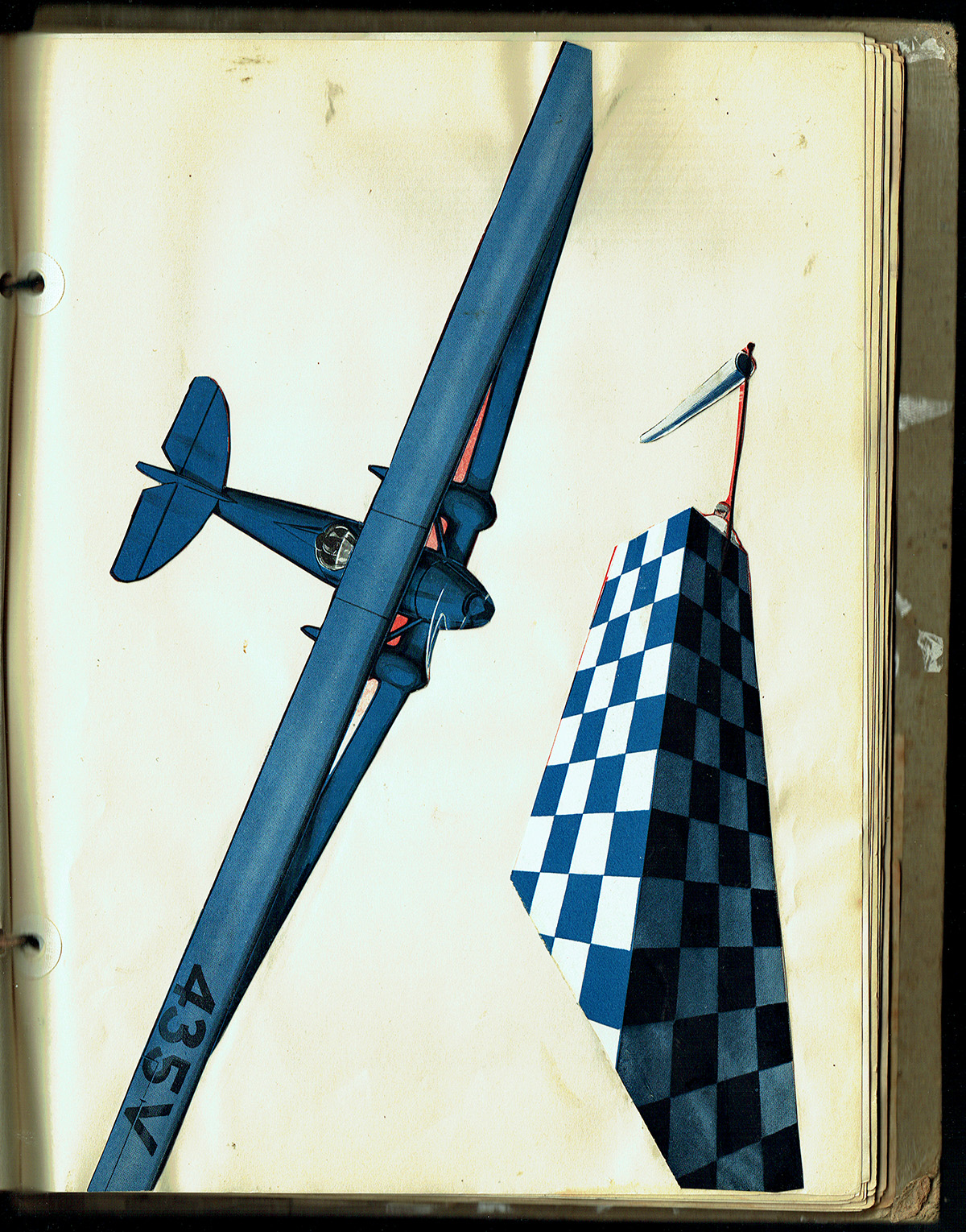

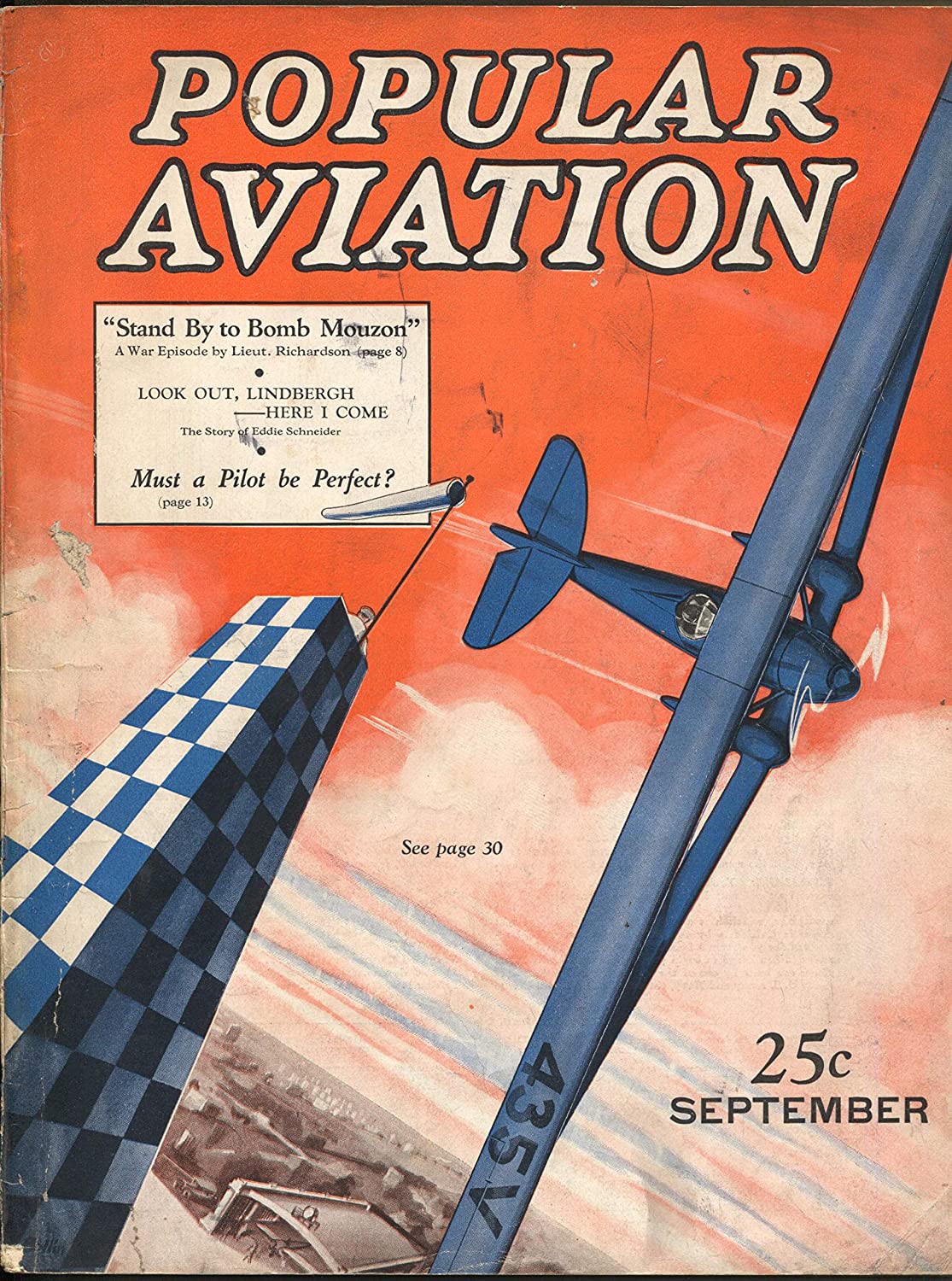

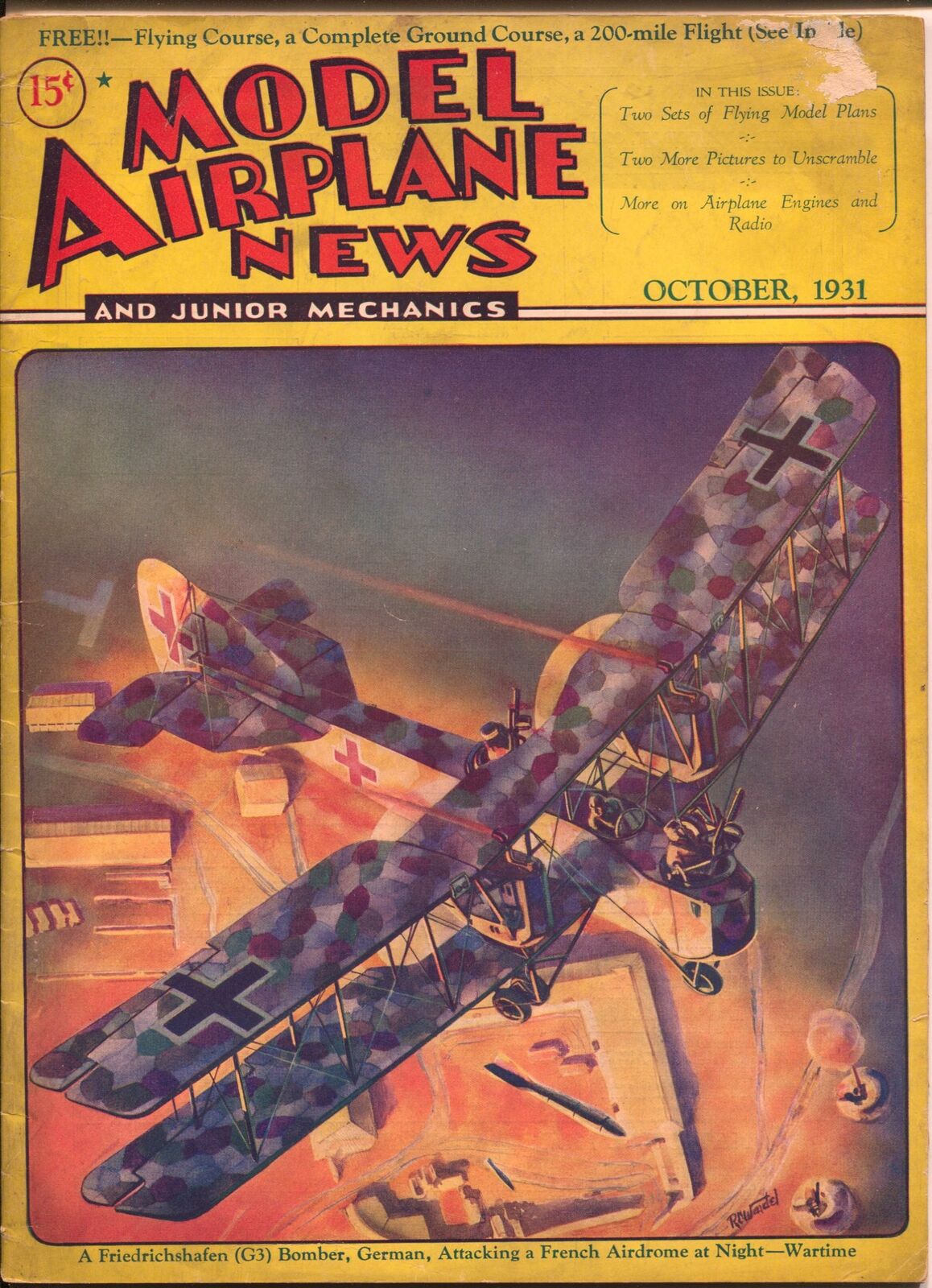

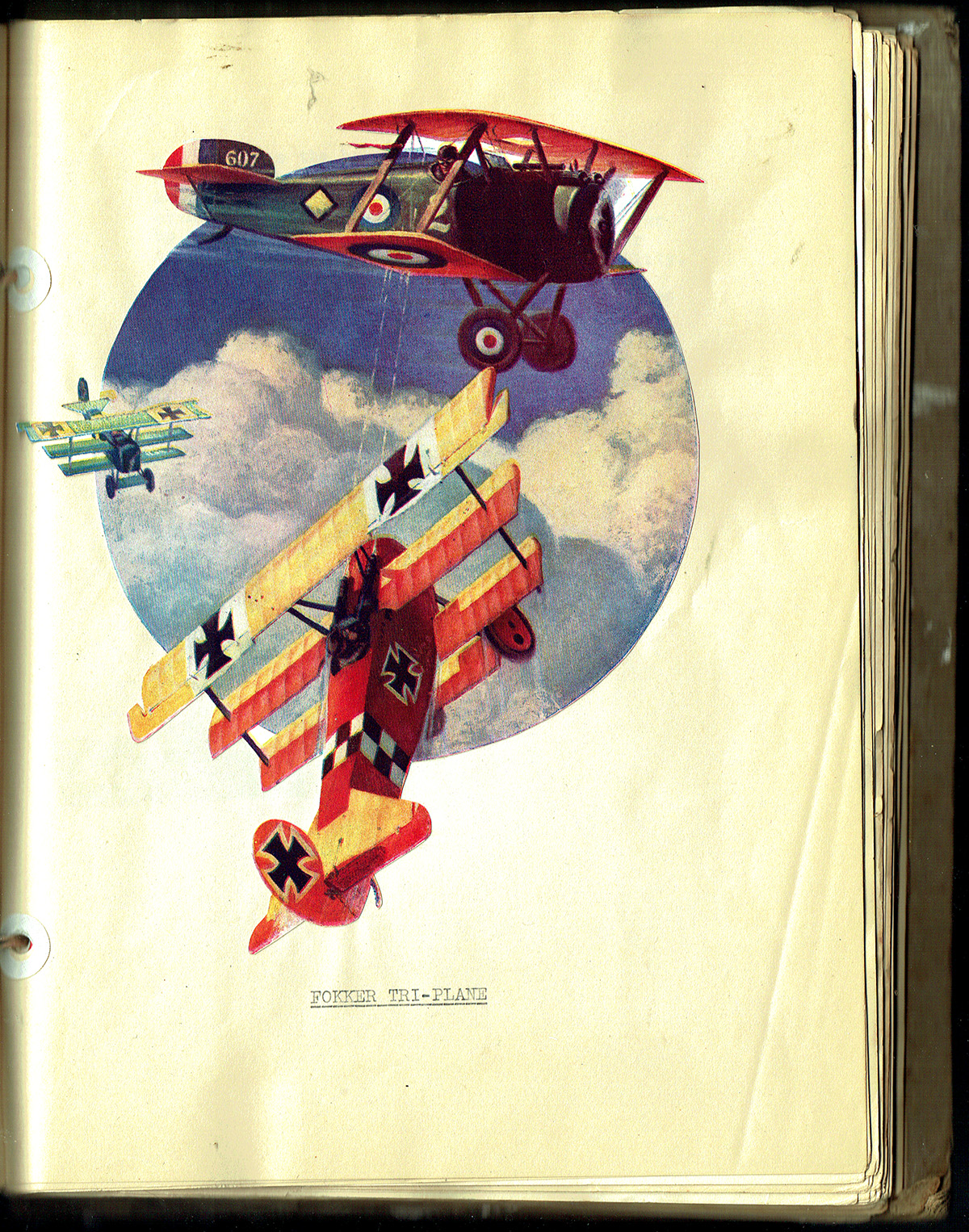

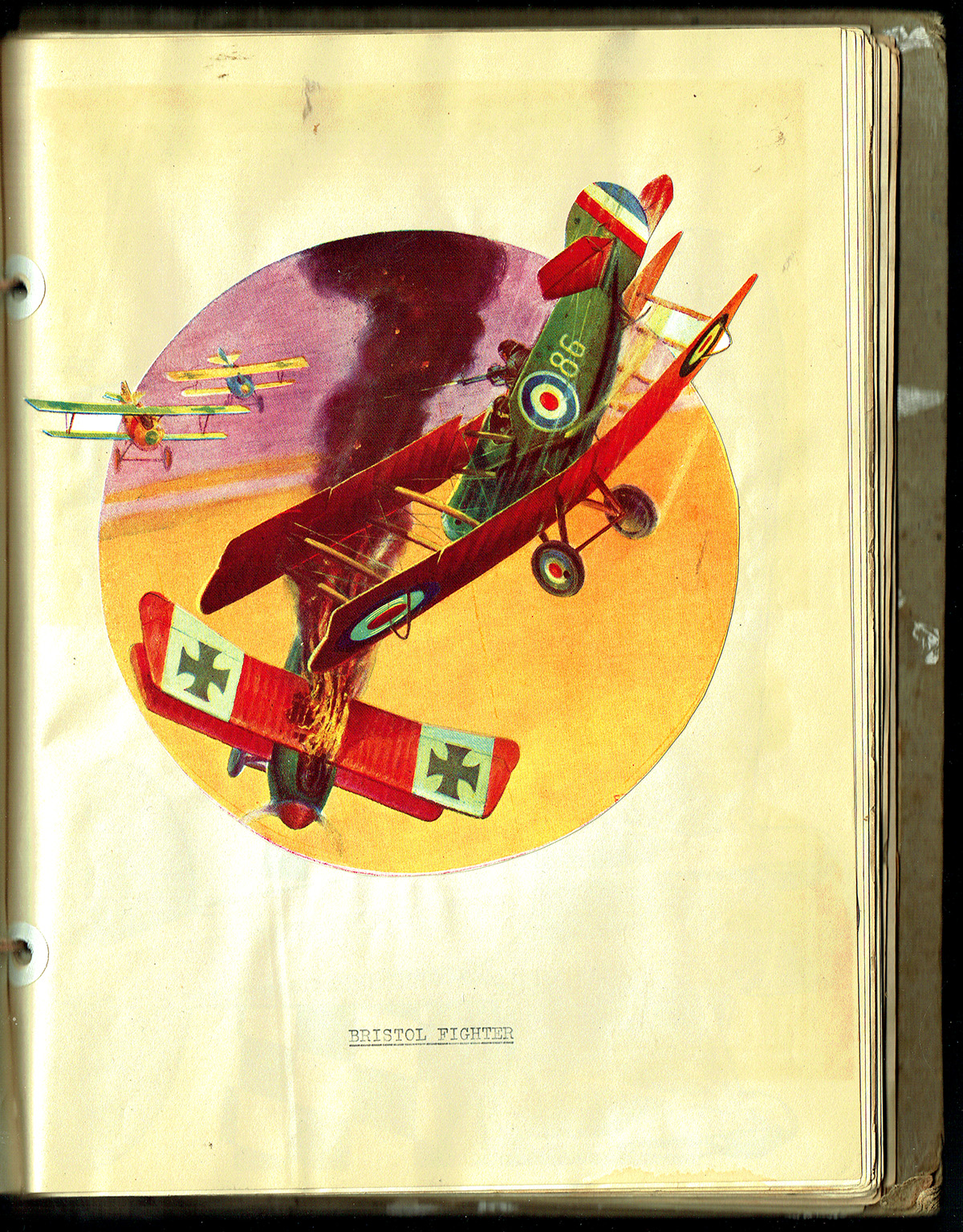

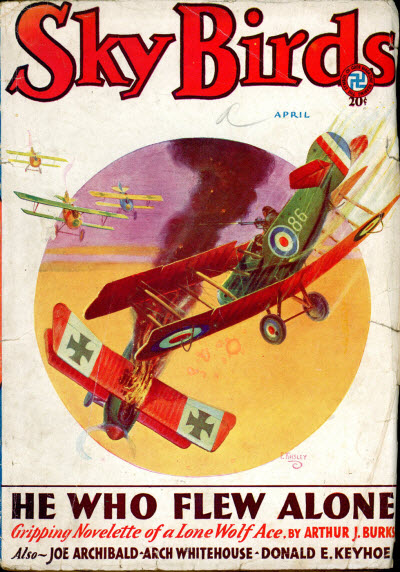

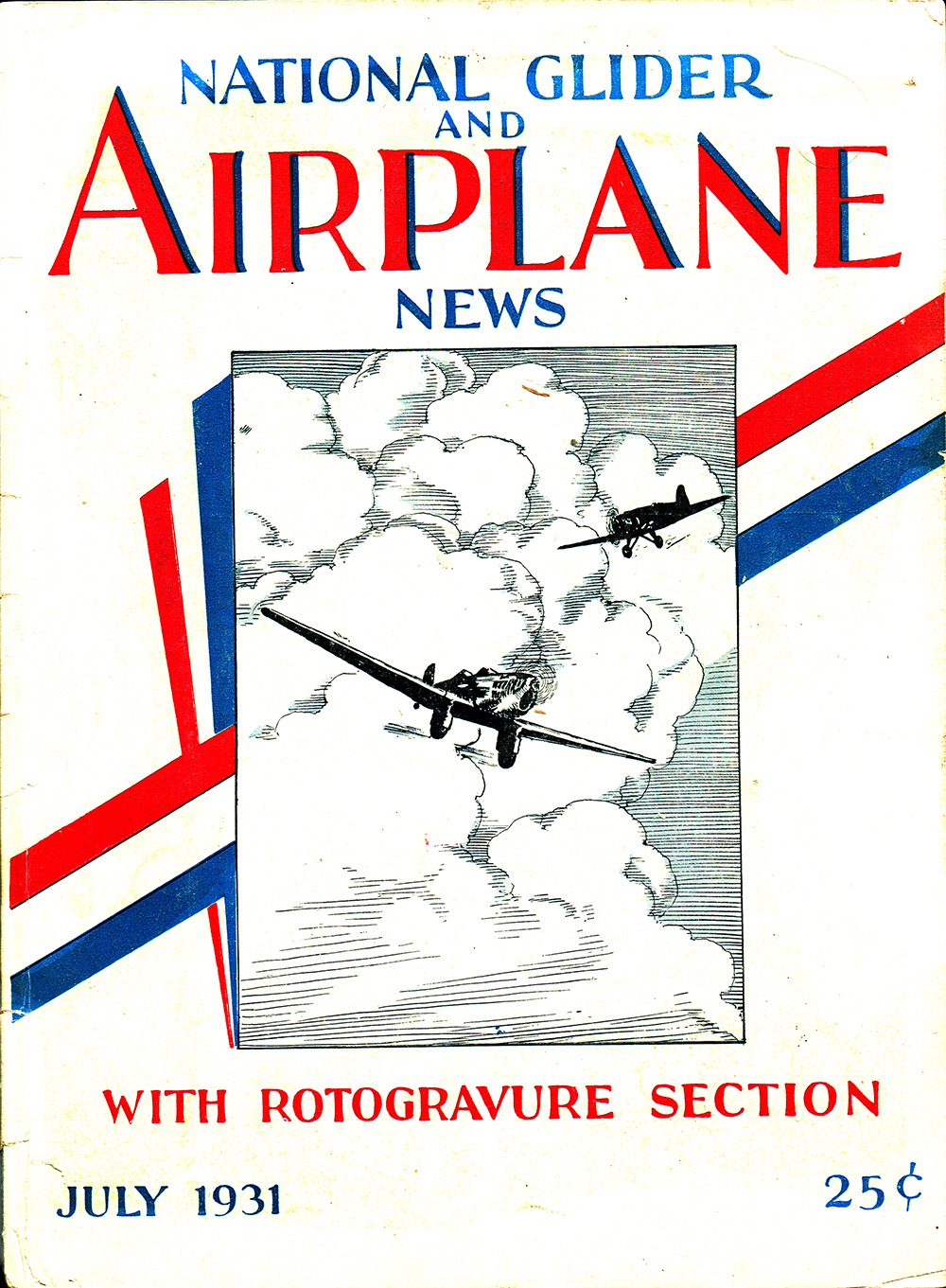

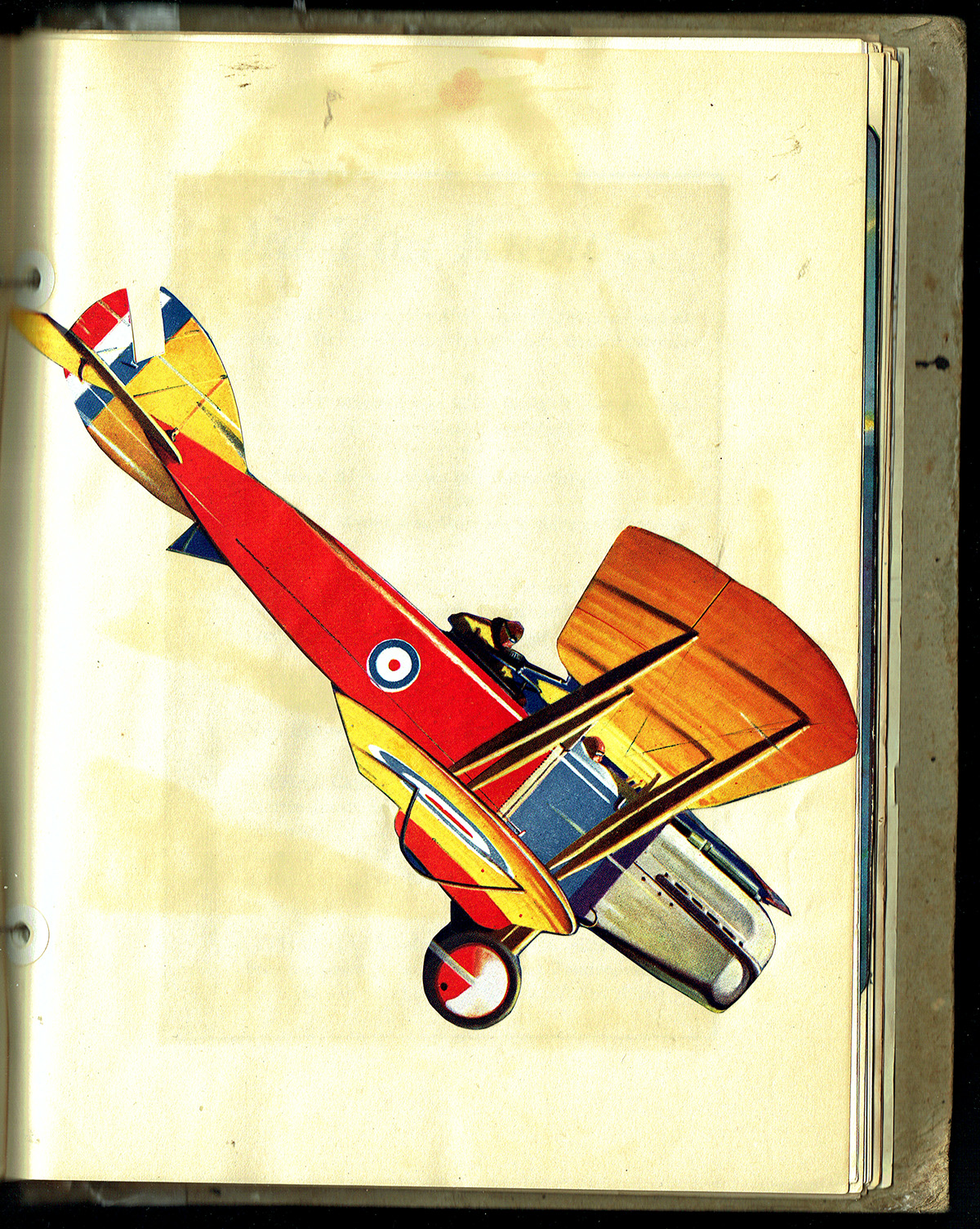

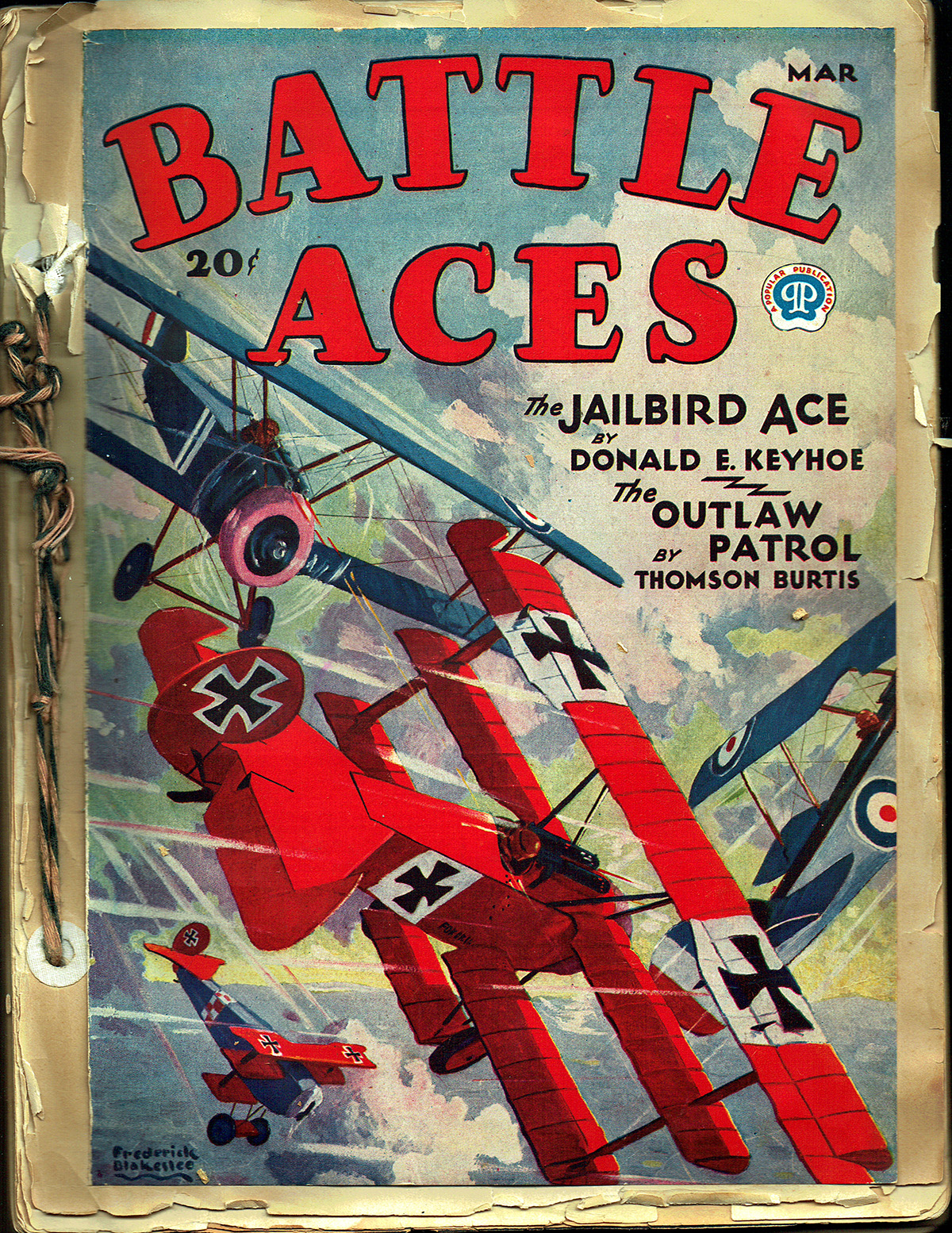

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!  Like many in the late 20’s and early 30’s, Robert O’Neil was fascinated with aviation and as such, a large part of both volumes of his scrapbooks is taken up with a cataloging of the many different types of planes. But amongst all the planes and air race flyers and info on Aces are some surprising items. Robert was also fond of including cut-outs from covers of all kinds of aviation themed magazines.

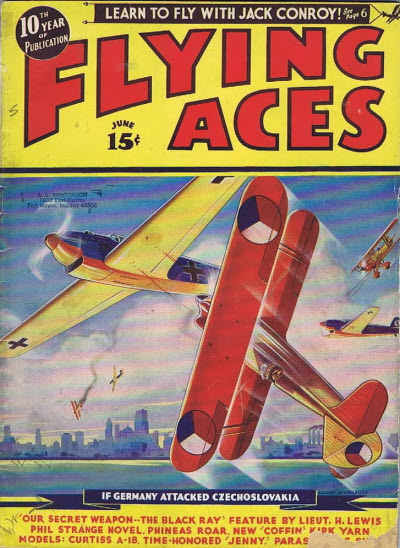

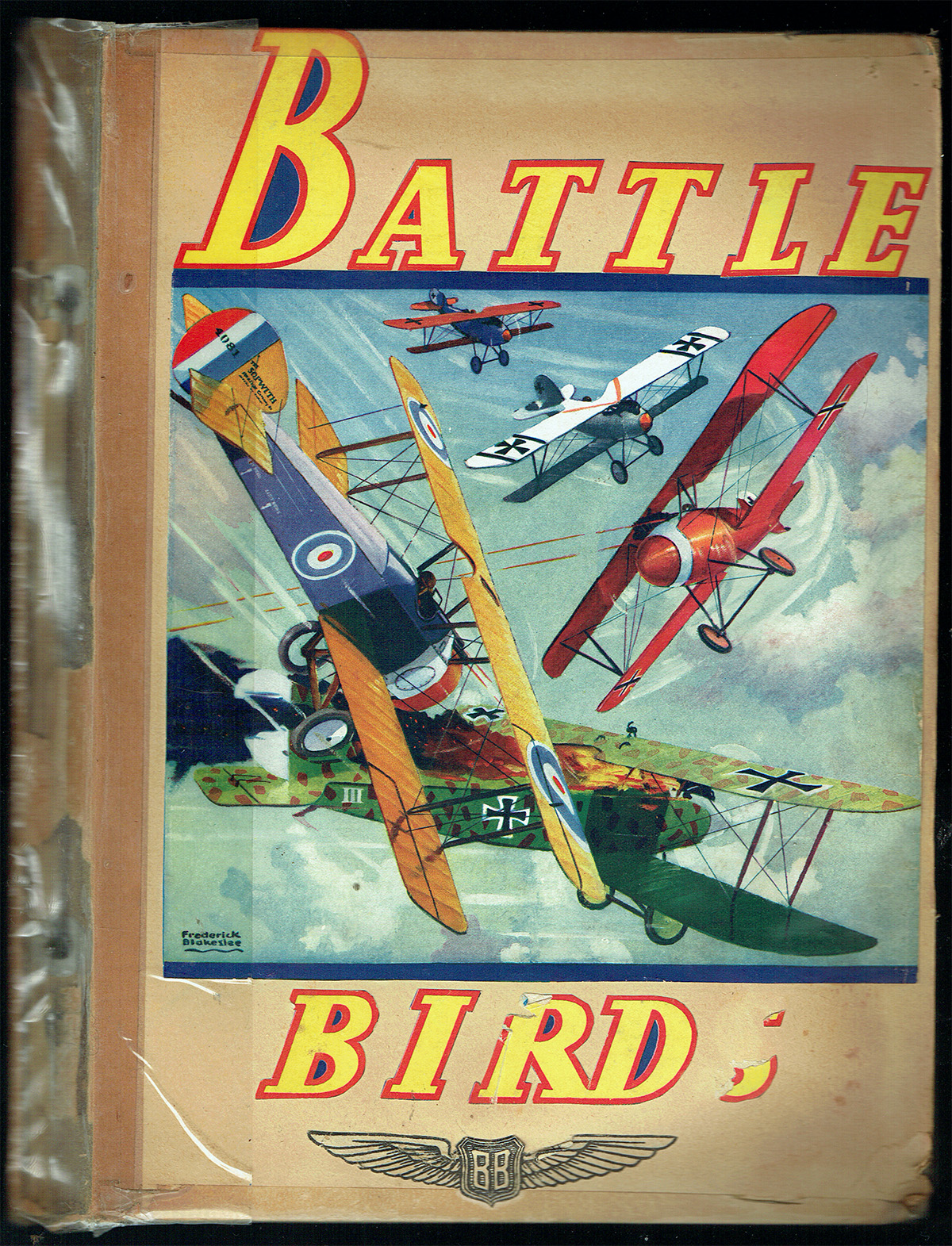

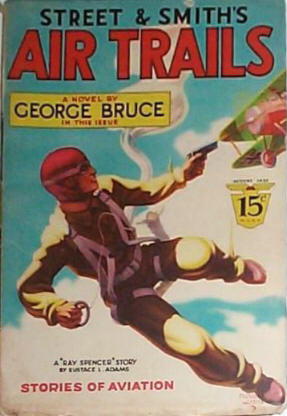

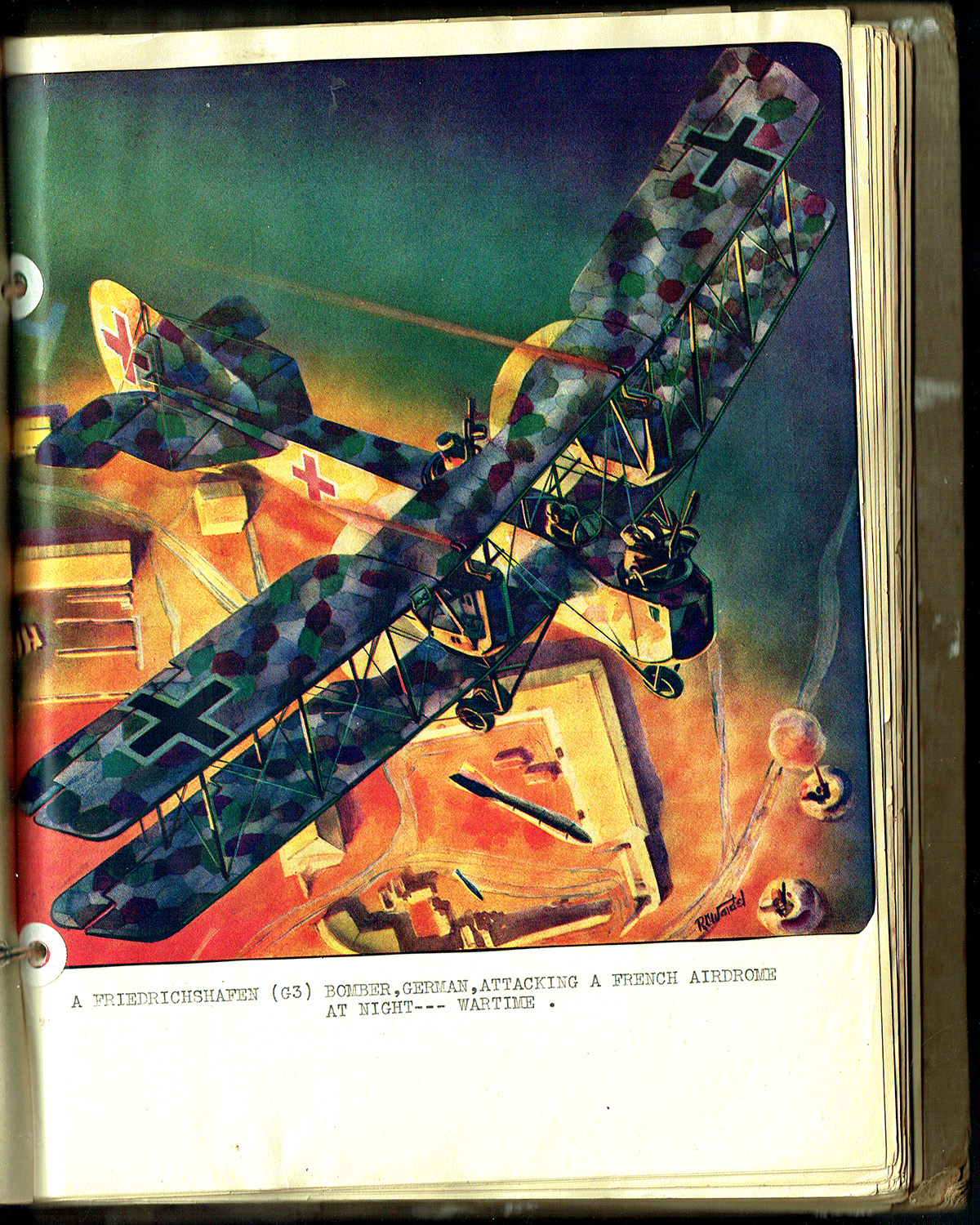

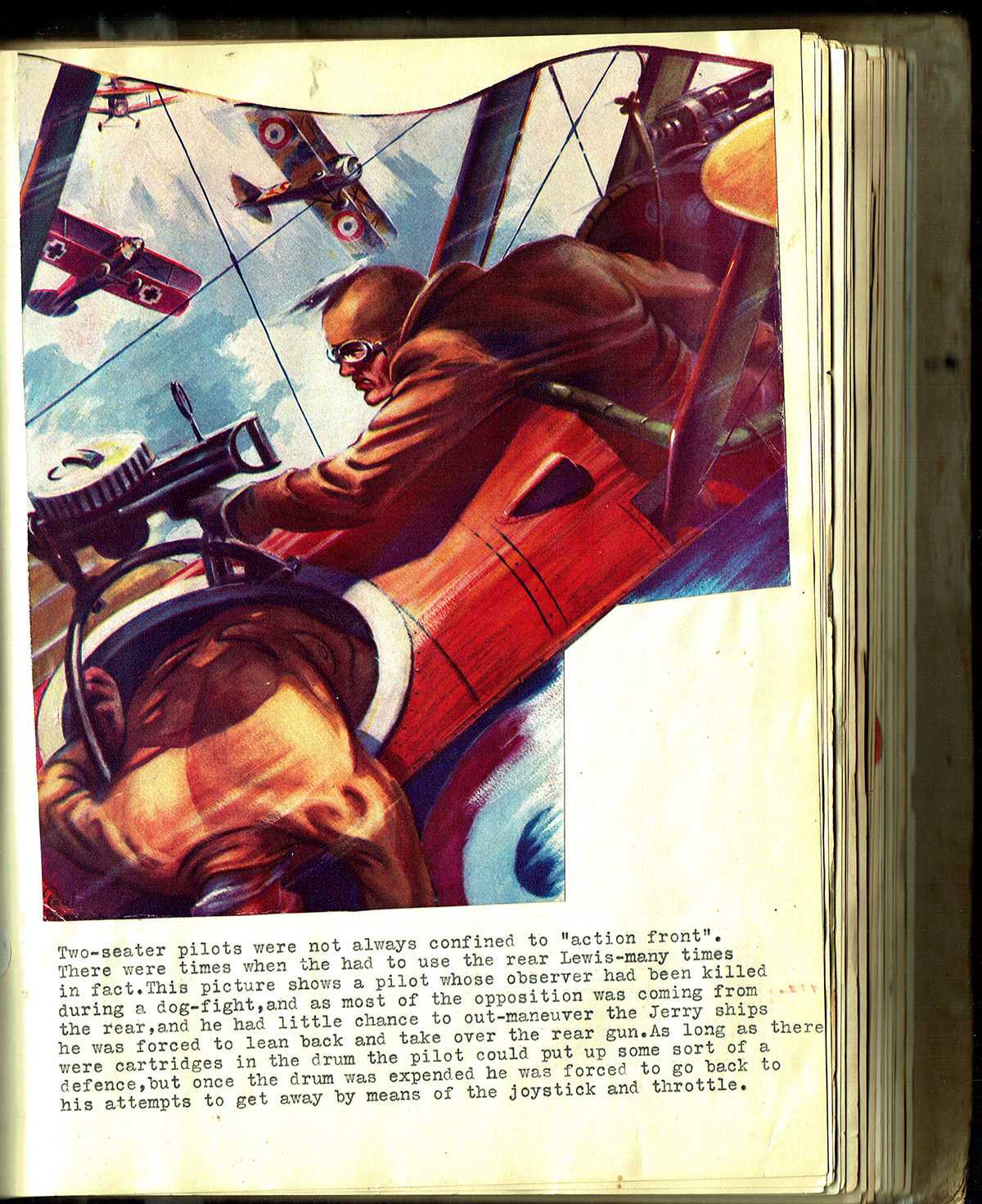

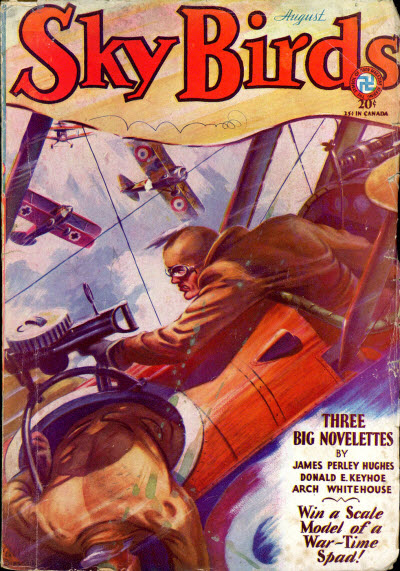

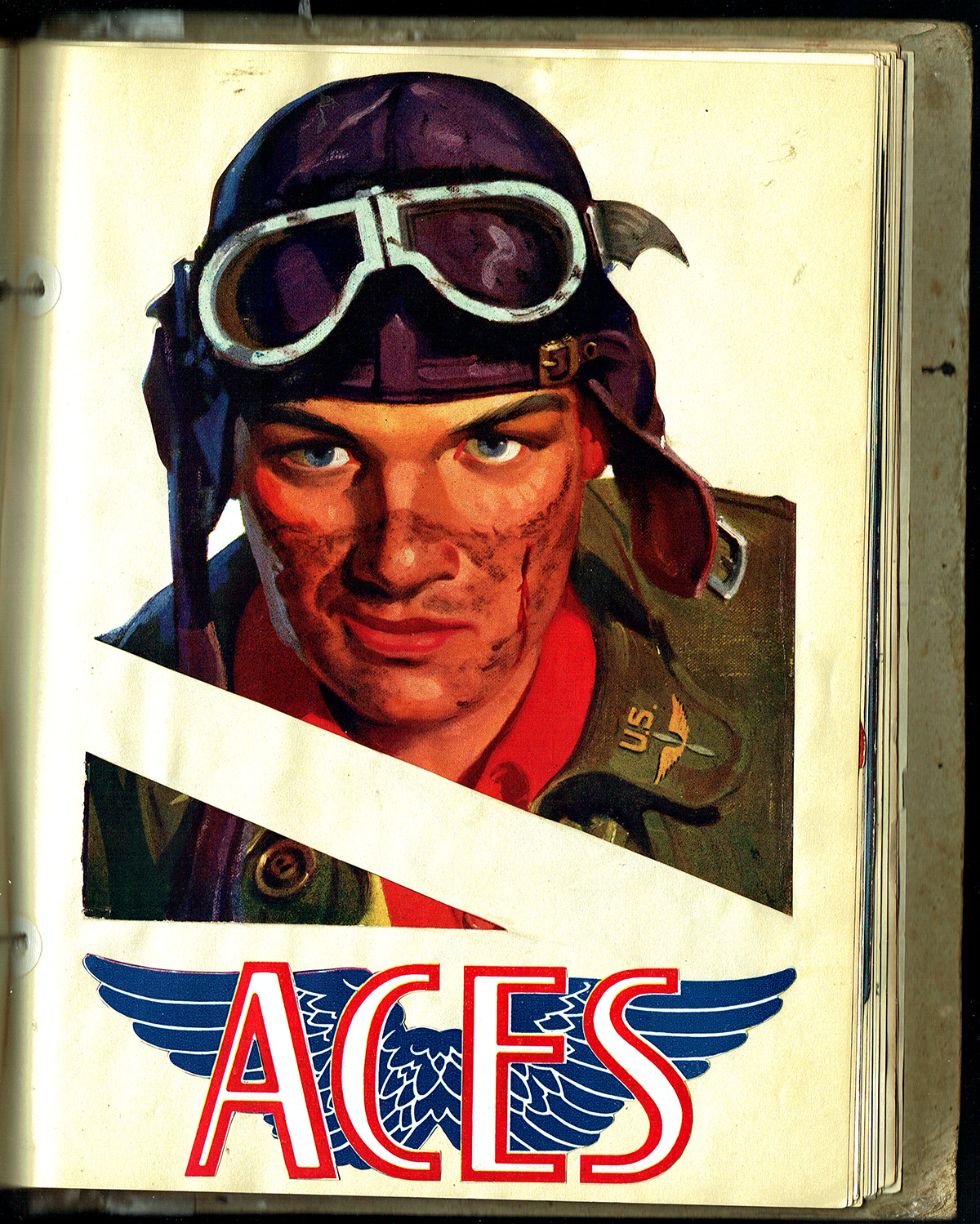

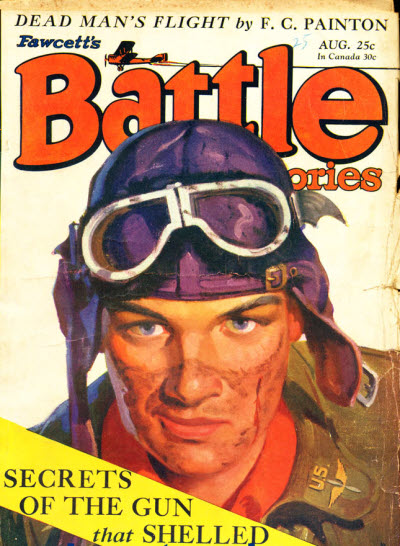

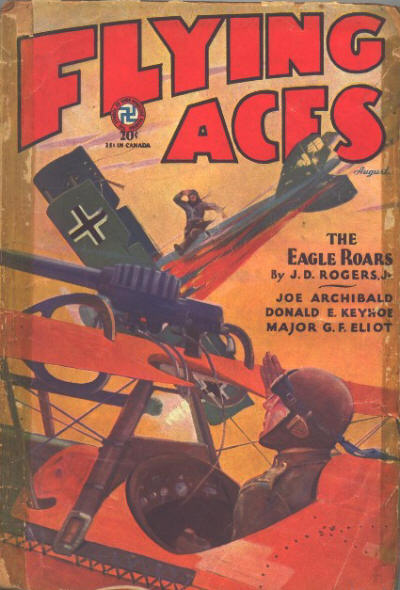

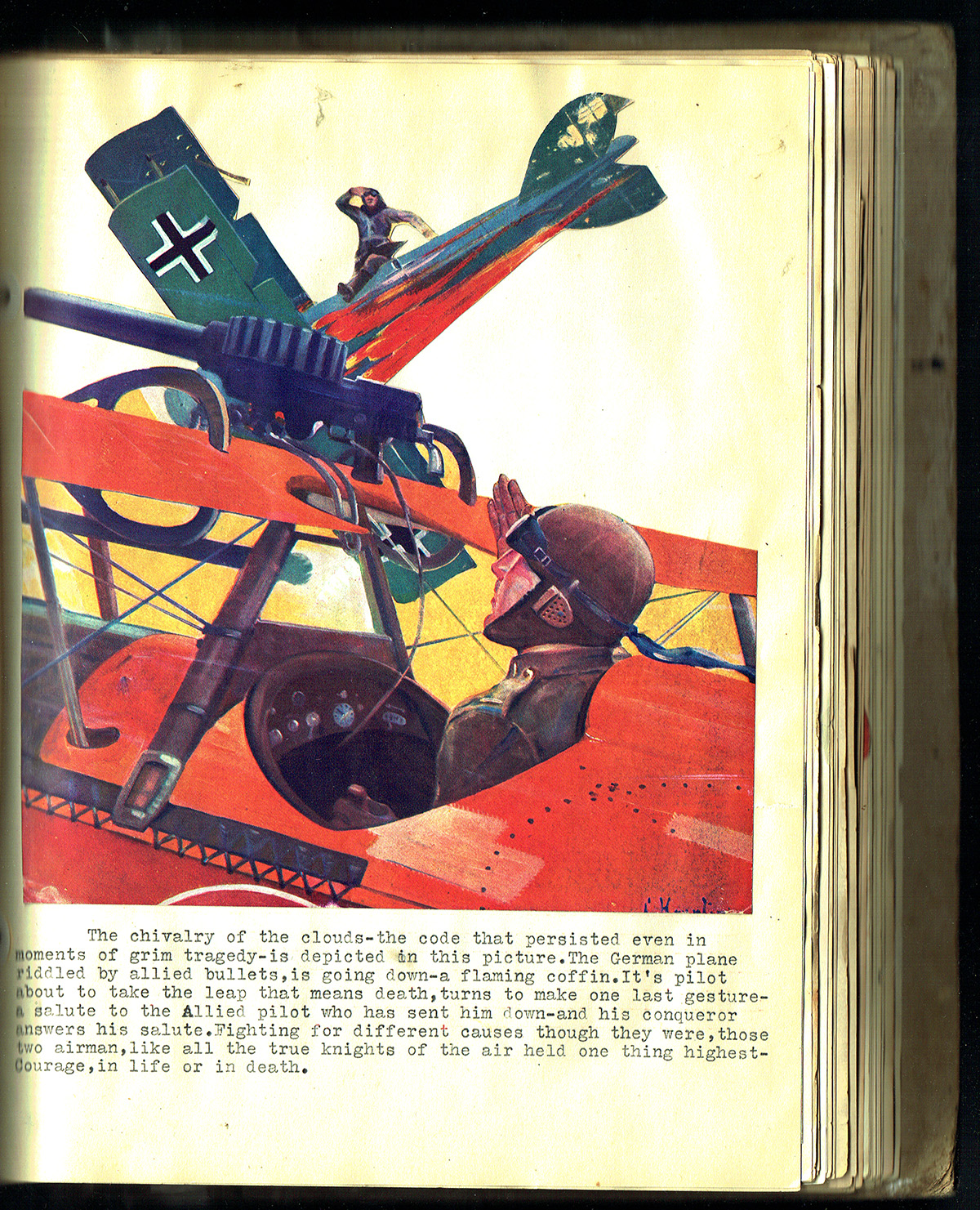

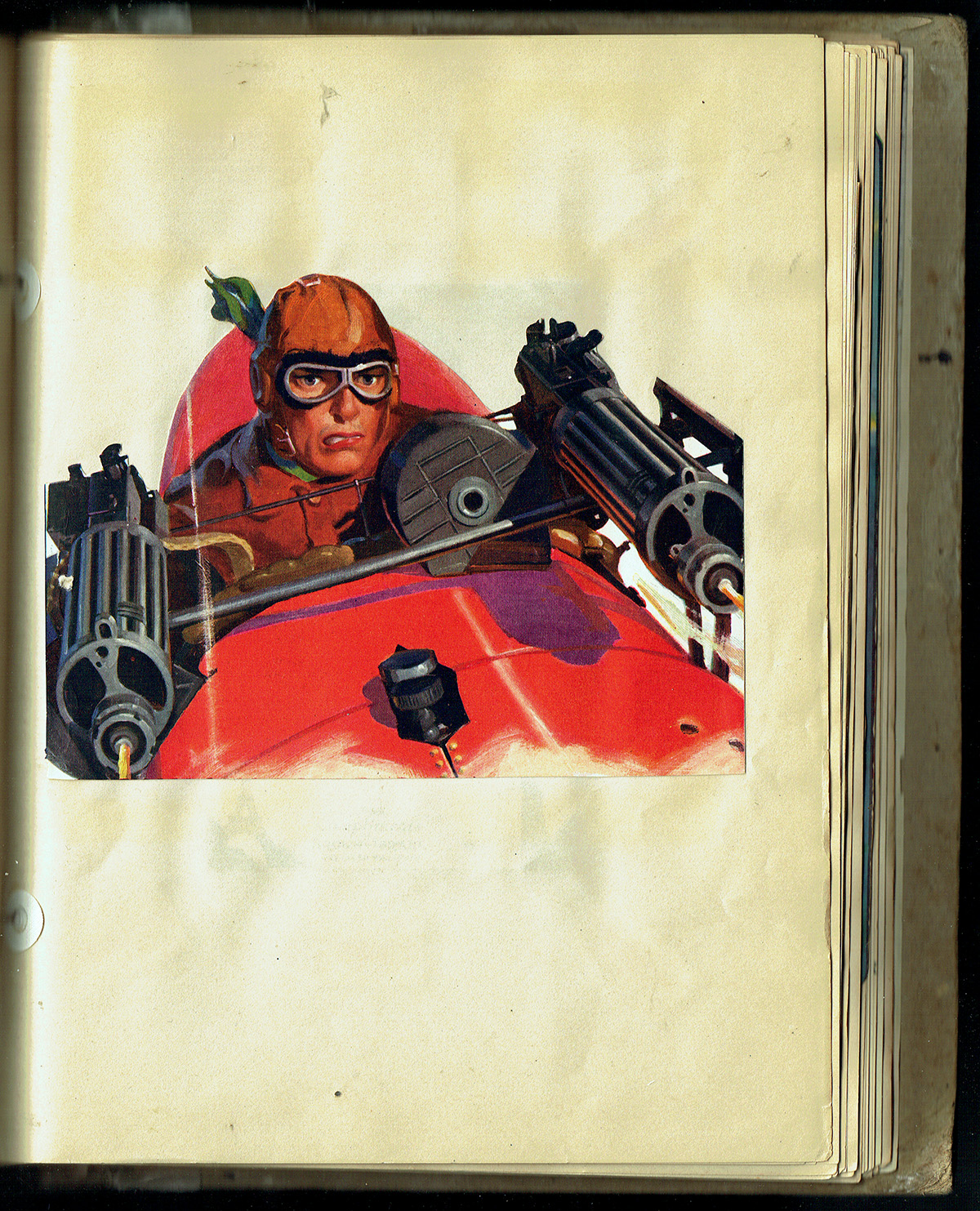

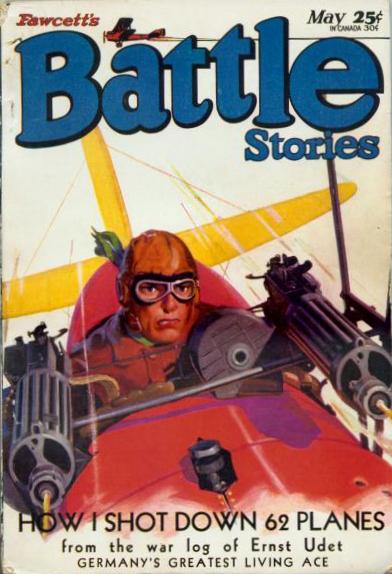

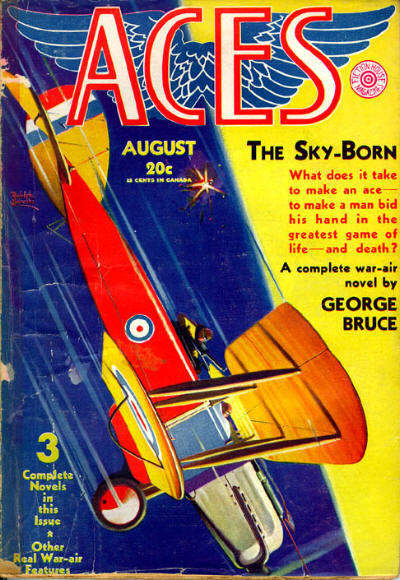

Like many in the late 20’s and early 30’s, Robert O’Neil was fascinated with aviation and as such, a large part of both volumes of his scrapbooks is taken up with a cataloging of the many different types of planes. But amongst all the planes and air race flyers and info on Aces are some surprising items. Robert was also fond of including cut-outs from covers of all kinds of aviation themed magazines.

Like many in the late 20’s and early 30’s, Robert O’Neil was fascinated with aviation and as such, a large part of both volumes of his scrapbooks is taken up with a cataloging of the many different types of planes. But amongst all the planes and air race flyers and info on Aces are some surprising items.

Like many in the late 20’s and early 30’s, Robert O’Neil was fascinated with aviation and as such, a large part of both volumes of his scrapbooks is taken up with a cataloging of the many different types of planes. But amongst all the planes and air race flyers and info on Aces are some surprising items.