The Brothers Oppenheim

TODAY marks the one hundred and tenth birthday of Three Mosquitoes scribe Ralph Oppenheim!

Ralph was born on March 29th, 1907 to James and Lucy (Seckel) Oppenheim. At the time of Ralph’s birth, James was a budding poet who would go on to become an author, poet, screenwriter, director and Jungian lay-analyst. Best remembered today as the founder and editor of the short-lived The Seven Arts Journal—”It’s not a magazine for artists, but an expression of artists for the community.”

In 1911, James and Lucy had another son and named him James. When James was born he was a golden boy—good-natured, healthy and beautiful; full of laughter and fat chuckles. He was the picture of health, but as he began to walk he was funny on his feet . . . until one day his legs didn’t seem to want to work. The doctor was called in. It was infantile paralysis—Polio.

Although this pronouncement may have been a burden to his parents, James Jr. tried not to let it get in the way. Ralph’s brother also tried his hand at writing, but was never the success in the pulps his big brother was. There are some verses and such in some of the Love pulps, but no blood and thunder stuff. When he started submitting poetry and verse to publications he decided it was best if he change his name so editors wouldn’t think his father had diminished in capacity—and so changed his name to Garrett.

Garrett found work as a journalist for the New York Herald-Tribune where he became acquainted with Dr. Leo Wollman, head of the New York Society of Clinical and Experimental Hypnotism. Upon the Herald-Tribune folding, Garrett became a hypnotist and counselor.

The Golden Handicap: A Spiritual Quest

A Polio Victim Asks, “Why?” and Turns His Life Around

In 1993 he wrote a book using his own life as case studies to help counsel the reader. In each chapter he would tell about a part of his life and then provide an analysis to counsel people in a similar situation. Garrett mentions Ralph throughout the early portion of the book as they’re growing up. Here we have chapter 9 from his book—sans analysis—My Big Brother and Me!

- Download “My Big Brother and Me” (The Golden Handicap: A Spiritual Quest. ARE Press, 1993)

Editor’s Note: If you are interested in reading Garrett’s whole book it can be found on used book sites and for as low as 90¢ used from other sellers on Amazon!

with Alan McLeod of the Royal Flying Corps, who was one of the youngest of the famous flying aces. Major Giuseppe Barracca, Ace of Aces of the Italian Flying Corps, was one of the oldest, being 34 years of age when he was killed in the desperate air fighting above the Piave. Like Captain Ritter von Schleich, he entered the war a cavalry officer, but soon was transferred to the more romantic, yet more hazardous branch of the army, the flying corps.

with Alan McLeod of the Royal Flying Corps, who was one of the youngest of the famous flying aces. Major Giuseppe Barracca, Ace of Aces of the Italian Flying Corps, was one of the oldest, being 34 years of age when he was killed in the desperate air fighting above the Piave. Like Captain Ritter von Schleich, he entered the war a cavalry officer, but soon was transferred to the more romantic, yet more hazardous branch of the army, the flying corps. the three Canadian airmen winning the coveted award of the Victoria Cross, the highest honor bestowed on its fighting heroes by the British Empire, He was the youngest flyer ever to receive the honor, having it pinned on his chest in appropriate ceremonies at Buckingham Palace a few months before his nineteenth birthday.

the three Canadian airmen winning the coveted award of the Victoria Cross, the highest honor bestowed on its fighting heroes by the British Empire, He was the youngest flyer ever to receive the honor, having it pinned on his chest in appropriate ceremonies at Buckingham Palace a few months before his nineteenth birthday. of that small number of American aviators who had actually had front line battle experience when his own country entered the war. Even before there were any indication* of his own country taking part, he sailed for France and enlisted in the French Army, where he was eventually transferred for aviation tralning. When the La Fayette Escadrille was formed, he wan invited to become a member. In that organization he won his commission as a Lieutenant in recognition of his ability and courage.

of that small number of American aviators who had actually had front line battle experience when his own country entered the war. Even before there were any indication* of his own country taking part, he sailed for France and enlisted in the French Army, where he was eventually transferred for aviation tralning. When the La Fayette Escadrille was formed, he wan invited to become a member. In that organization he won his commission as a Lieutenant in recognition of his ability and courage. one of the most modest and unassuming of the great flying aces. When the war began he was an engine mechanic with the then recently formed Royal Flying Corps. After flying training he became a Sergeant pilot, and began, piling up the string of victories which eventually placed him at the top of all the British aces. He was progressively promoted to Lieutenant, Captain and Major, and won every medal possible, including the Victoria Cross.

one of the most modest and unassuming of the great flying aces. When the war began he was an engine mechanic with the then recently formed Royal Flying Corps. After flying training he became a Sergeant pilot, and began, piling up the string of victories which eventually placed him at the top of all the British aces. He was progressively promoted to Lieutenant, Captain and Major, and won every medal possible, including the Victoria Cross. Immelmann was the first of the great German Aces. Immelmann scored victory after victory over the Allied flyers until his total score mounted higher than that of any of the Allied Aces.

Immelmann was the first of the great German Aces. Immelmann scored victory after victory over the Allied flyers until his total score mounted higher than that of any of the Allied Aces. American Ambulance section, serving in that unit attached to the French armies from February 26th, 1916, to May 11th, 1918. In the early spring of ‘18 he transferred to the aviation. He became a member of the famous Stork squadron of the French Flying Corps.

American Ambulance section, serving in that unit attached to the French armies from February 26th, 1916, to May 11th, 1918. In the early spring of ‘18 he transferred to the aviation. He became a member of the famous Stork squadron of the French Flying Corps. was one of the American flying aces who saw service under two flags. He began his career with the French before America entered the war. At first he served with the Ambulance Corps, but was later transferred to aviation, where he established a reputation as one of the most daring flyers on the front.

was one of the American flying aces who saw service under two flags. He began his career with the French before America entered the war. At first he served with the Ambulance Corps, but was later transferred to aviation, where he established a reputation as one of the most daring flyers on the front. was one of the most famous of the French flying aces. Along with Guynemer, Navarro and Nungesser, he furnished the spectacular flying news that filled the newspapers in the early days of the World War. He was credited with over forty victories and only the great Guynemer topped him in the list of French aces during his time on the battle front.

was one of the most famous of the French flying aces. Along with Guynemer, Navarro and Nungesser, he furnished the spectacular flying news that filled the newspapers in the early days of the World War. He was credited with over forty victories and only the great Guynemer topped him in the list of French aces during his time on the battle front. famous Italian poet and dramatist and enthusiastic patriot, was one of the most colorful and forceful of Italian flyers in the early days of the World War. He enlisted early in the most spectacular branch of the army, the Italian Air Corps. Soon after completing his training he was assigned to a bombardment squadron which was charged with harassing the then fast-advancing Austro-German armies, which threatened to overwhelm the brave Italian defenders and take the capitol at Home. By exerting superhuman efforts the Italians prevented that.

famous Italian poet and dramatist and enthusiastic patriot, was one of the most colorful and forceful of Italian flyers in the early days of the World War. He enlisted early in the most spectacular branch of the army, the Italian Air Corps. Soon after completing his training he was assigned to a bombardment squadron which was charged with harassing the then fast-advancing Austro-German armies, which threatened to overwhelm the brave Italian defenders and take the capitol at Home. By exerting superhuman efforts the Italians prevented that. much the name means to those few who knew how he fought and died. His front line career was short, hectic and dynamic. He blazed across the war-torn skies of France like a flaming meteor. Very few people ever heard of Luke during his short but Sensational career on the Western Front. His fame and name came after he died. He is recognized now as the most courageous, the most audacious war bird that ever handled a control stick and pressed the Bowden triggers mounted on it. Only Eddie Rickenbacker topped him in the final list of American Aces after the War was ended. Rickenbacker was officially credited with 26 victories. Frank Luke had 21. But the comparison is hardly fair to Luke, for Rickenbacker was on the front for almost six months, while Luke’s front line career lasted only a little over two weeks. Even in that short space of time he had worked up to the top and was the American Ace of Aces when he died. There is no telling what, score he would have run up, if fortune had been more in his favor. The story below he told to Sergeant John Monroe, who was a favorite of his.

much the name means to those few who knew how he fought and died. His front line career was short, hectic and dynamic. He blazed across the war-torn skies of France like a flaming meteor. Very few people ever heard of Luke during his short but Sensational career on the Western Front. His fame and name came after he died. He is recognized now as the most courageous, the most audacious war bird that ever handled a control stick and pressed the Bowden triggers mounted on it. Only Eddie Rickenbacker topped him in the final list of American Aces after the War was ended. Rickenbacker was officially credited with 26 victories. Frank Luke had 21. But the comparison is hardly fair to Luke, for Rickenbacker was on the front for almost six months, while Luke’s front line career lasted only a little over two weeks. Even in that short space of time he had worked up to the top and was the American Ace of Aces when he died. There is no telling what, score he would have run up, if fortune had been more in his favor. The story below he told to Sergeant John Monroe, who was a favorite of his. French flier, was the moat spectacular and colorful of all the flying Aces. Young, tall, slender, but in very poor physical health, he was a veritable demon in the air, He had absolutely no regard for his own personal safety. Time after time be attacked single-handed whole squadrons of enemy planes. On the ground he was shy, reserved, and spoke very few words to anyone. Whenever he came to Paris on his very infrequent leaves from the front to secure medical aid, the whole city was decorated in festive attire in his honor. He was the toast of the boulevards, the darling of the French populace. And the whole world mourned his passing when he died, shot down by a comparatively obscure German pilot, who got in a chance shot from exceedingly long range. The German pilot, Wisseman, never knew until afterward that it was the great Guynemer that he had shot down. When Guynemer passed mysteriously into the blue, he was officially credited with 57 enemy aircraft and universally recognized as the Ace of Aces of all the armies.

French flier, was the moat spectacular and colorful of all the flying Aces. Young, tall, slender, but in very poor physical health, he was a veritable demon in the air, He had absolutely no regard for his own personal safety. Time after time be attacked single-handed whole squadrons of enemy planes. On the ground he was shy, reserved, and spoke very few words to anyone. Whenever he came to Paris on his very infrequent leaves from the front to secure medical aid, the whole city was decorated in festive attire in his honor. He was the toast of the boulevards, the darling of the French populace. And the whole world mourned his passing when he died, shot down by a comparatively obscure German pilot, who got in a chance shot from exceedingly long range. The German pilot, Wisseman, never knew until afterward that it was the great Guynemer that he had shot down. When Guynemer passed mysteriously into the blue, he was officially credited with 57 enemy aircraft and universally recognized as the Ace of Aces of all the armies. of the flying forces were not on the Allied side. The enemy also had its heroic figures.

of the flying forces were not on the Allied side. The enemy also had its heroic figures. was the first of the Royal Flying Corps pilots to make a distinguished record. Unlike the French, the British made no mention of their air pilot’s victories. One day Ball wrote home that he had just counted his 22nd victory. His mother proudly showed this letter to her friends. Ball was disbelieved.

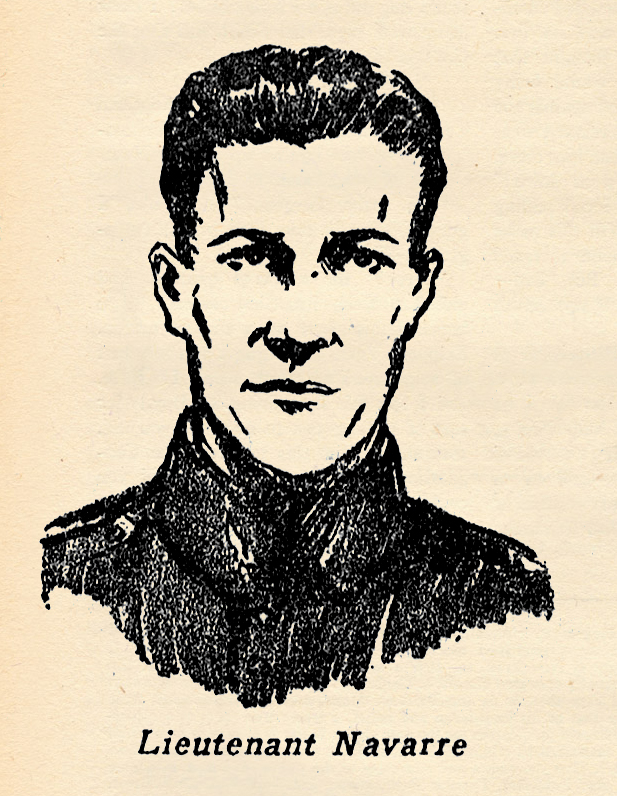

was the first of the Royal Flying Corps pilots to make a distinguished record. Unlike the French, the British made no mention of their air pilot’s victories. One day Ball wrote home that he had just counted his 22nd victory. His mother proudly showed this letter to her friends. Ball was disbelieved. America entered the War, there was one name that was consistently emblazoned in the papers along with Marshal Joffre, Earl Kitchner, and the other high ranking generals. It was the name of Navarre, the “Sentinel of Verdun.” Navarre was the first Ace, the first man to destroy live enemy aircraft in plane to plane combat. At the first battle of Verdun he did yeoman duty. It was his reports brought in after solo patrols far in the rear of the German lines that enabled Marshal Joffre to so dispose his defense troops at Verdun that the attacking armies under the command of the German Crown Prince were never able to take the city.

America entered the War, there was one name that was consistently emblazoned in the papers along with Marshal Joffre, Earl Kitchner, and the other high ranking generals. It was the name of Navarre, the “Sentinel of Verdun.” Navarre was the first Ace, the first man to destroy live enemy aircraft in plane to plane combat. At the first battle of Verdun he did yeoman duty. It was his reports brought in after solo patrols far in the rear of the German lines that enabled Marshal Joffre to so dispose his defense troops at Verdun that the attacking armies under the command of the German Crown Prince were never able to take the city.