Here’s a nifty little article from the pages of the September 1942 issue of Writer’s Digest, the leading and largest writer’s magazine. Every issue is a gem. There’s usually articles about how to write for certain genres and markets; listings of the publications and opportunities available in different regions; and the letters column which frequently features letters from authors and publishers of the day.

Here’s a nifty little article from the pages of the September 1942 issue of Writer’s Digest, the leading and largest writer’s magazine. Every issue is a gem. There’s usually articles about how to write for certain genres and markets; listings of the publications and opportunities available in different regions; and the letters column which frequently features letters from authors and publishers of the day.

THE AIR-WAR PULPS

By Richard Cromwell • Writer’s Digest, September 1942

A GOOD MARKET that many able writers are passing up are the air-war pulps, by which I mean the magazines that feature the American or British hero and fighting in the air in either the first world war or the present conflict. Such publications are legion. Many of the better known ones are Fighting Aces, Battle Birds, Dare-Devil Aces, and Sky Fighters. Writing for these magazines is comparatively easy once one has learned the rules of the game. And these pulps do pay well.

Do these periodicals stick to the formula? What type of character is preferred? What length? These same questions arc asked every day by writers. In this article, I hope to answer them.

These magazines stick so decidedly to formula that most of the situations and plots are so threadbare that they are distasteful. People are beginning to tire of the same old thing done up in a different package every month. A writer who can produce something fresh will be eagerly welcomed into this group.

The veterans are afraid to change from their moth-eaten plots to something new and fresh. Why? Simply because they know that if they turn out something which is original, and the editor does not like it, they are in danger of losing their steady markets. Authors who continue to write hackneyed stuff arc on the way out. Don’t start out using beaten-to-death plots or you shall regret it.

One of the most shopworn plots, one which you should steer safely away from, is this fragile example. Flying hero goes out on patrol with the rest of his flight-mates. The patrol is engaged by the enemy. Something goes wrong with hero’s guns or engine, and he is forced to pull out and limp back to his home base. Going back, his engine or gun trouble clears up. When he lands, he is flatly accused of deserting his mates. The members of the squadron begin to hate him like poison. After another forced pull-out, he is threatened with a court-martial or some other form of punishment. He escapes, steals a plane, and heads for Hunland, determined to make it plenty hot for the Germans in his last hour. An enemy flight intercepts him. Climaxing a bitter fight, during which he shoots down several Germans, he has to make a forced landing. Holding off the enemy ground troops with his machine guns, he makes the necessary repairs, takes off after being wounded and goes back, to home field. Upon landing there, he is greeted by his fellow-officers, who have found they had been wrong about him.

Writers of air stories would do well to make a study of different aircraft and parts. For instance, a pilot always refers to the power plant as “the engine” instead of “the motor.” Be very careful about stunts. Here are some of them: the loop, wing-over, Im-melmann turn, chandelle, snap-roll, aileron or slow roll, and the outside loop. These stunts are used in military flying. Study the ground terms, personnel of an airport, flying terms, weather, etc. One book which will give you all of this is “The Air Story Writer’s Guide,” published by the Digest’s book department. The price is only twenty-five cents.

What type of character is preferred? The red-blooded, he-man type fits the bill. He should be a hell-raiser and always in the midst of trouble. However, make your main character sympathetic to the reader and give him strong motivation in order to make the story convincing.

As to the length, 5,000 words is the best for one who is just trying to break into these markets. After you sell a few short stories, then is the time to try a novelette. It is best not to aim at the longer yarns at first, not until you get some experience.

Before sending in a yarn to a specific magazine, write the editor a letter asking what he likes personally. Lots of writers don’t advise this, but I have found that it is better than making a blind stab at the target. Some editors have peculiar dislikes. When you enter into a correspondence with an editor, you are making the first sure step toward the goal.

Now is the greatest period of all times for beginning writers to break into the pulp air-war magazines. New air publications are springing up constantly — in a never-ending stream. Millions of words by new writers are being printed every month. Some magazines use the very cheapest sort of material, especially if their editorial budget is down, and the editors must buy the best they can get at their ½ cent a word rate. But, in order to find your place in these markets, you must study the different magazines month in and month out. Do not merely glance at them. Study the kind of characters they use, the type of story, the advertisements.

At the present time, I am writing air-war yarns for Collier’s. While we are talking about pulps, I believe that the type of plot used in my current slick story is the sort which would appeal to the readers of the pulp sheets. The hero is not the do-or-die individual with whom we are so readily familiar. Instead, he is a mental coward. He can not face the ghosts in his mind. For that reason, he never went to bed until 4 o’clock in the morning; he loafed in the canteen until that time. The excerpt which I have taken from the yarn reveals what he fears, and definitely establishes him as a strange character. It goes as follows:

Benton said coldly, “You’ve changed, Steve. Why, I can remember when you joined the R.A.F. six months ago; how excited you were when you were transferred to this squadron ; how—”

“That was six months ago,” Armitage said. “Six months can be a lifetime when you’re in a war.”

Benton studied him closely. “In reality, you’re not a coward. You’re just trying

to do an impossible thing. Hide from yourself.”

“Aw, I don’t know what’s wrong with me, Larry.” Armitage rested his head in his hands.

“I’m slowly going nuts. And I have to drink to wash the ghosts from my mind. But you wouldn’t know anything about that, would you?”

“I know all about it.”

“Remember last week, Larry? I sent a Nazi down in flames that day. And just before the fire closed over him, I saw his face. It was like a face from Satan’s own pits. But that man didn’t die. He still lives—in my dreams every night. A face with scorched skin, hair ablaze—”

How do you like Armitage? One way to keep the reader’s attention is to present unusual characters. Strive to do that thing, and you will add a lot to your story.

Do you open a story with thudding fists and scraping feet? Plenty of inexperienced writers open a story like that, and most of the time, the fight has absolutely no bearing on the yarn. It is just thrown in for effect, to catch the reader’s eye. Of course, if the fight has some definite purpose, it is all right. A good trick, for the first three or four paragraphs, is to surround the protagonist in mystery and to place against him such odds as to make his situation appear hopeless. For example:

Conover knew he was about to die. But he didn’t fear dying so much. He had always thought he would relch and scream as lead pounded into his body. Slugs were eating into his body now, and he didn’t do either of those things.

Von Schiller and his crew were coming in to finish him off. The Baron lashed around. Steel-jacketed death battered into the Hurricane’s greenhouse, then into the office. A grimace split Gonover’s face into a million lines as a bullet found his side. A pool of blood covered his flying jacket. Crimson trickled from his mouth in warm streams. The instrument panel burst into a mess of tin and glass and wood. Gasoline poured through the wrecked panel and onto the floor boards—

Now you can see that our hero is in a hell of a fix. The worse you make it, the better the reader likes it. The hero’s squadron can be dragged onto the scene in time to save his neck.

I’ve tried my best to tell you a bit about the air-war pulps. I don’t know whether I’ve succeeded or not. Hope I have.

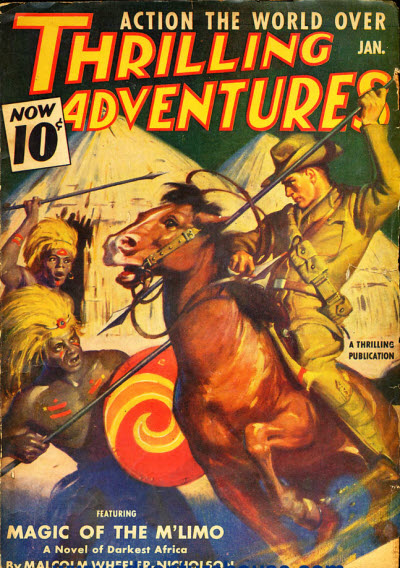

Canada’s very own Harold F. Cruickshank this month. One of the most successful series of animal wilderness stories Cruickshank produced was the “White Phantom†series which primarily ran in the pages of Thrilling Adventures and West magazines.

Canada’s very own Harold F. Cruickshank this month. One of the most successful series of animal wilderness stories Cruickshank produced was the “White Phantom†series which primarily ran in the pages of Thrilling Adventures and West magazines.

Here’s a nifty little article from the pages of the September 1942 issue of Writer’s Digest, the leading and largest writer’s magazine. Every issue is a gem. There’s usually articles about how to write for certain genres and markets; listings of the publications and opportunities available in different regions; and the letters column which frequently features letters from authors and publishers of the day.

Here’s a nifty little article from the pages of the September 1942 issue of Writer’s Digest, the leading and largest writer’s magazine. Every issue is a gem. There’s usually articles about how to write for certain genres and markets; listings of the publications and opportunities available in different regions; and the letters column which frequently features letters from authors and publishers of the day.