How the War Crates Flew: Tricky Ships

FROM the pages of the November 1932 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

Tricky Ships

by Robert Sidney Bowen (Sky Fighters, November 1932)

POWERLESS to do a single thing about it, the members of the 23rd pursuits watched the lone Camel flatspinning down to total destruction. Its pilot was plainly visible, battling the controls. But his frantic efforts were to no avail. Seconds later the nose struck, flames leaped skyward, and another pilot was added to the long list of tricky ship victims. . . .

And that, fledglings, was the way more than one Hun-getter checked in his chips during the late war . . . a victim of a tricky ship, not Spandaus lead. Now, don’t go getting the idea that those lads were dumb pilots, else they wouldn’t have allowed their crates to throw them. That’s not the idea at all. More than a few crack pilots got into trouble with a tricky ship and lost the decision. What we are going to try and point out this meeting is that during the late war a peelot had to be a heads-up peelot for reasons other than those manufactured in Germany.

Present day ships are so well designed and constructed that you can almost go to sleep and let them fly on by themselves. They are steady as a rock even in pretty punk weather, and when anything does happen there is always the good old ’chute-pack on your back. All you have to do is step overboard, count six and pull the ring. But the war crates? Ah, there you have something different . . . mighty different, and don’t you forget it! In the first place, they were all designs of 1914-1918 vintage, naturally. Designers didn’t know as much then as they do now. And, there were no parachutes for pilots. The Germans started using ’chutes during the last year of the war, but the Yanks, English and French never had them except for balloon work.

That statement may surprise you, after some of the war-air yarns that you’ve been reading. But it happens to be a fact, and any war peelot will check on that statement.

But to get back to the business of these tricky ships. That questionasking fledgling over there in the corner looks like he’s ready to burst with curiosity, so I’ll talk fast and maybe choke him off.

JUST for the heck of it, we’ll take some of the war crates, one by one, and elaborate on their tricky features and peculiarities.

Of course, the Sopwith Camel is the first on the list. Of all the tricky ships that crossed over No-Man’s-Land the Camel was the trickiest of them all. A wonderful stunting crate, and great stuff in a dog scrap, but my, my, how you had to watch that baby and check its tendency to throw you for a flock of wooden kimonos!

The Camel was powered with a Clerget, Le Rhone, and later for high altitude work, with a 210 Bentely. All three were rotary engines. And all three gave the ship its nasty desire to flip over and down on right wing and into a tight spin. It was propeller torque that did that. As I explained at another meeting, propeller torque is a tendency for a ship to go in the opposite direction to the rotation of the propeller blades. In a Camel the prop rotated from right to left (standing in front of the prop). Therefore the ship would try to swing to the right (the pilot’s right when in the cockpit). Naturally, the way to counteract that was to keep on a bit of left rudder all the time. In other words, when you wanted to make a right bank you really eased up a bit on left rudder and let the torque carry you around, instead of actually putting on right rudder. The Camel was also rigged to whip around on a dime, and that helped the engine torque idea all the more. There was no dihedral on the top wings, but there was about two degrees on the bottom ones.

What’s that? What’s dihedral?

Well, Fledgling, dihedral of airplane wings is the angle of a wing upwards and outwards to the horizontal. In other words, if a wing is pefectly flat it has no dihedral, but if it tilts upwards it has. No dihedral reduces the horizontal stability of a plane, and in this way. The area under a tilted flat wing is the same on either side of the fuselage. But when there is dihedral the area (called horizontal equivalent) becomes increased on the down-tilted side and increased on the up-tilted side. Therefore the natural reaction is for the plane to right itself to an even keel.

Naturally the dihedral on the lower wings of a Camel was put there so that the ship wouldn’t fly completely wild, but still be a fast maneuvering ship. Never having experienced such a thing, I can’t go on record definitely, but I would say that flying a Camel with no dihedral on any of the wings would be just like going down a mountain road at midnight, with both headlights on the blink. You’d just hang on and pray that you didn’t hit anything.

WHENEVER a pilot slipped up in alertness and engine torque whipped a Camel over on its right wing, it always fell into a tight spin. Now a spin is nothing to get grayhaired about, even in a Camel, if you have altitude. BUT, the camel was so darn sensitive to the controls that when you took it out of a spin you had to be mighty careful lest it didn’t flip right over into a spin in the opposite direction. In case you don’t know, you stop a plane from spinning by moving the controls as though you wanted the ship to spin in the other direction. But as soon as the ship stopped spinning the original way, you checked its tendency to flop over on the opposite side, and began to get the nose up. In a Camel split-second checking was in order. You couldn’t take your time about it. The instant the ship stopped spinning you had to check and get the nose up, else you went spinning down in the opposite direction, and had the whole darn job to do all over again.

THERE was also another tricky feature of the Camel, and one which cost many lives. That was the tendency of the ship to go past the vertical when diving.

You would start a steep dive in a Camel and unless you watched the ship the nose would start to swing back to the rear, and before you knew it you were diving backwards as though you were going to pull an outside loop. The way to get out of that was to pull the stick back so that the nose would start moving forward, and then when you got vertical again to slowly ease the nose up. But it was right at that moment when a lot of chaps checked out of the world, and for this reason. When a Camel’s nose starts back toward the vertical, after being past it, it comes slowly at first but as it reaches the vertical it develops a vicious tendency to whip upward in a zoom. If you don’t check that and hold the ship steady in a vertical dive, and ease up slowly, why, the result is that you lose your wings. The savage up-thrust of the plane, with the top surfaces of the ship broadside to the line of motion, just wipes the wings off as though they were so much paper.

Now, if you’ve been listening to me, instead of falling asleep like that fledgling over there, why, you’ll realize that both of the principal tricky features of a Camel can be hooked up together. But, in case you don’t, it’s like this. You’re buzzing along, and start to make a right bank, a split-arc turn. You take off too much left rudder, and zowie, engine torque whips you over to the right and into a spin. You start to take it out, don’t check it in time and zowie, it flops over into an opposite spin. You start to take it out, check it this time, but before you realize it you’re diving past the vertical before you’ve had time to start getting the nose up. Well, you try to get the nose forward to the vertical, and then when it gets to the vertical you don’t hold it steady. Zowie the plane zooms up, the wings come off, and zowie . . . no more peeloting for you in this world! Now, do you get the idea?

ANOTHER tricky ship that Sopwith also made was the Sopwith Pup. Strictly speaking, it wasn’t what you’d call a dangerous ship. It was simply a crate that made you stay awake if you cared anything about seeing the girl friend again. It was a very small job, and naturally very light. And being light, it floated like a feather. And as it floated like a feather, the job of landing was just that much more difficult. Time and time again (until you got the hang of things) a greenhorn pilot would overshoot the field. Of course that’s okay provided the engine is still functioning. You simply feed it the hop, go around and try again. But in the event of a forced landing, why, the story was different. You only had one chance then, and if you didn’t make good you were just out of luck. The Pup came out before the Camel but was used mostly for training purposes. It was so small and light that it couldn’t stand the gaff in a dog-scrap.

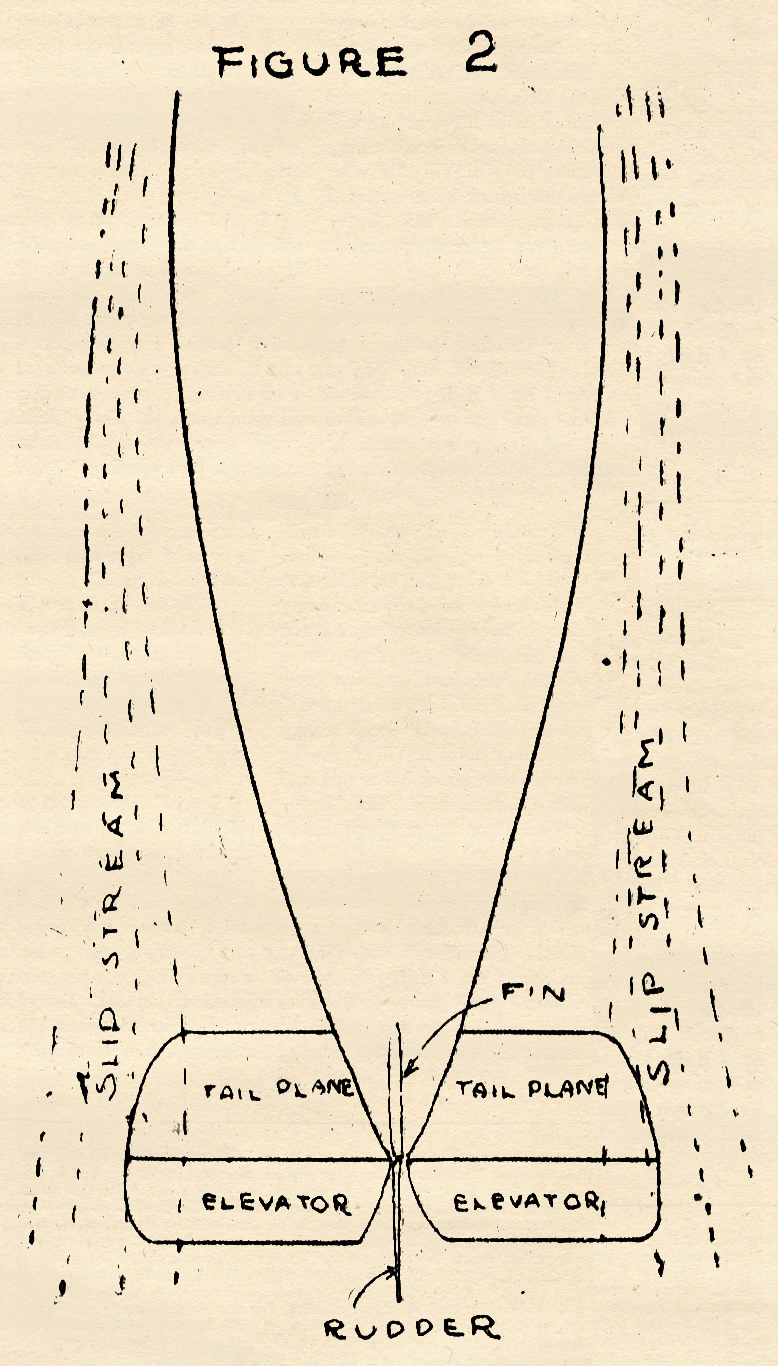

In the early part of 1918 the Sopwith outfit came out with a ship called the Snipe. It was an improvement on the Camel, and was intended for high altitude work. Only two Snipe squadrons got out to France before the Armistice, and those only for a few weeks. But they certainly knocked the pants off the Fokkers, which proves what swell ships they were. The first model was known as the Unmodified Snipe. It was the tricky job. The fuselage was barrel shaped and the rudder and tail surfaces a bit too small. The result was that when you got into a spin it was the task of your life-time to get it out.  The reason for that was this. The fuselage being so big and the tail surfaces so small, the slip-stream didn’t strike all of the surfaces. When the ship went into a spin an air-lock would be formed between the rudder and the elevators. That would practically render the controls useless. In other words the tail surfaces were so blanketed by the size of the fuselage that they wouldn’t get the proper grip on the air. (Fig. 2.) Once the ship got into a spin it was difficult to present a flat spin developing when you tried to take it out. It was practically impossible to come out of a flat spin. What you had to do was go back into a tight spin again and make another try to get past the flat spinning point. Just so’s you won’t be too confused about my jabbering, a tight spin is when the wings revolve about the fuselage as the axis. And a flat spin is when the plane pivots around the nose in a gyroscopic motion. In other words, the plane is at a slight angle to the vertical and the whole plane goes swinging around in a circle, sidewise.

The reason for that was this. The fuselage being so big and the tail surfaces so small, the slip-stream didn’t strike all of the surfaces. When the ship went into a spin an air-lock would be formed between the rudder and the elevators. That would practically render the controls useless. In other words the tail surfaces were so blanketed by the size of the fuselage that they wouldn’t get the proper grip on the air. (Fig. 2.) Once the ship got into a spin it was difficult to present a flat spin developing when you tried to take it out. It was practically impossible to come out of a flat spin. What you had to do was go back into a tight spin again and make another try to get past the flat spinning point. Just so’s you won’t be too confused about my jabbering, a tight spin is when the wings revolve about the fuselage as the axis. And a flat spin is when the plane pivots around the nose in a gyroscopic motion. In other words, the plane is at a slight angle to the vertical and the whole plane goes swinging around in a circle, sidewise.

Yeah, no fooling, a spin in an Unmodified Snipe was not so hot. We speak from experience about that item. One day during a joyhop we slipped into a spin at ten thousand feet, and it took us just eight thousand feet to get out of it. Another two thousand feet and yours truly wouldn’t be here chinning with you fledglings.

Later that fault was corrected in what was called the Modified Snipe. The elevators were made a bit bigger and the ship had a balanced rudder and balanced ailerons. And if you don’t know what those things are, why, just take a look at Fig. 3.

THE well known Spad might be called a tricky ship because it was more or less a flying brick, and didn’t have much of a gliding angle. Naturally, all that means that the Spad was heavy, and it was, darned heavy in proportion to the wing surface. Under full power it was a sweet ship, but when you cut the gun you had to look out. The nose just plopped right down and you started diving hellbent. In the event of a forced landing you had to decide on your field mighty quick, because you didn’t have much time to think it over. You just naturally lost ground too fast. We once had a Spad forced landing. The engine konked at two thousand feet and we were just able to make two and one-half gliding turns to get into a field. But, of course, maybe a GOOD pilot could have made five. Now, you know what we think of us!

Speaking of landing reminds me of the Sopwith Dolphin, a high altitude scout that came out in 1918. The cockpit was right under the top wing. In fact we got into it through an opening in the wing. It was a smooth job until it came time to land . . . then, hold her Newt! If you ground looped it was just too bad. Why? Well, you usually went over on your back, and there you were, head down in the cockpit and no way to get out because the opening in the top wing was right smack against the ground. And if the ship caught fire . . . well, you can figure that out for yourself! After several chaps got burned alive or had their necks broken, braces were put on the top wing so as to give the peelot exit room when he needed it.

A LOT of your heros in this mag fly the good old S.E.5 and S.E.5a, but we can’t list either as a tricky ship, because it was only tricky when the peelot was just plane dumb. We mean this. The S.E. had what was known as an adjustable tail plane. In other words, from the cockpit you could adjust the tail plane (section to which the elevators are attached), so that it would tilt up or down. In other words, you could make the ship nose heavy or tail heavy, just as you wished. When taking off you would tilt the tail plane upward and that would help you get into the air sooner. And in landing you’d do the same thing because the reaction would be for the nose to go up, and thus you would have less trouble getting the tail down for a nice three point landing. But when you forgot about that tail-plane the ship got real tricky. For instance, you might pile into an S.E., slam home the juice and go tearing across the field. If the tail-plane happened to be tilted down you’d probably dig your prop into the ground. Another case is when you’re landing and over-shoot the field. Well, you feed the hop to go around again, and pull back the stick to get more altitude. Well, if the tail plane has been tilted up, as it should be for a landing, why, you’ll just go zooming up quicker than you expected, and if you don’t re-adjust the tail plane you’ll find yourself on your back at a rather low altitude for that sort of thing. So, of course, S.E. peelots remembered that they had a tail-plane just like they remembered they had an engine in the nose!

WELL, here comes that hard-boiled C.O. of this mag, and the look in his eye says, scram. But before I do, just let me lip another word or two. Don’t get the idea that we bohunks who flew the war crates were supermen. Far from it, believe you, me! But some of the ships were tricky, as I’ve been explaining, and the war peelot who went to sleep on the job, or didn’t keep his mind on the race, was asking for a lot of trouble that wasn’t German-made, either. But even a dumb peelot could handle them okay, if he paid attention to his knitting. And the very fact that we used to fly them, and are still alive, proves the above statement beyond all possible argument.

And the same to you! S’long!