Painton’s Letters Home from WWI | 24 January 1919

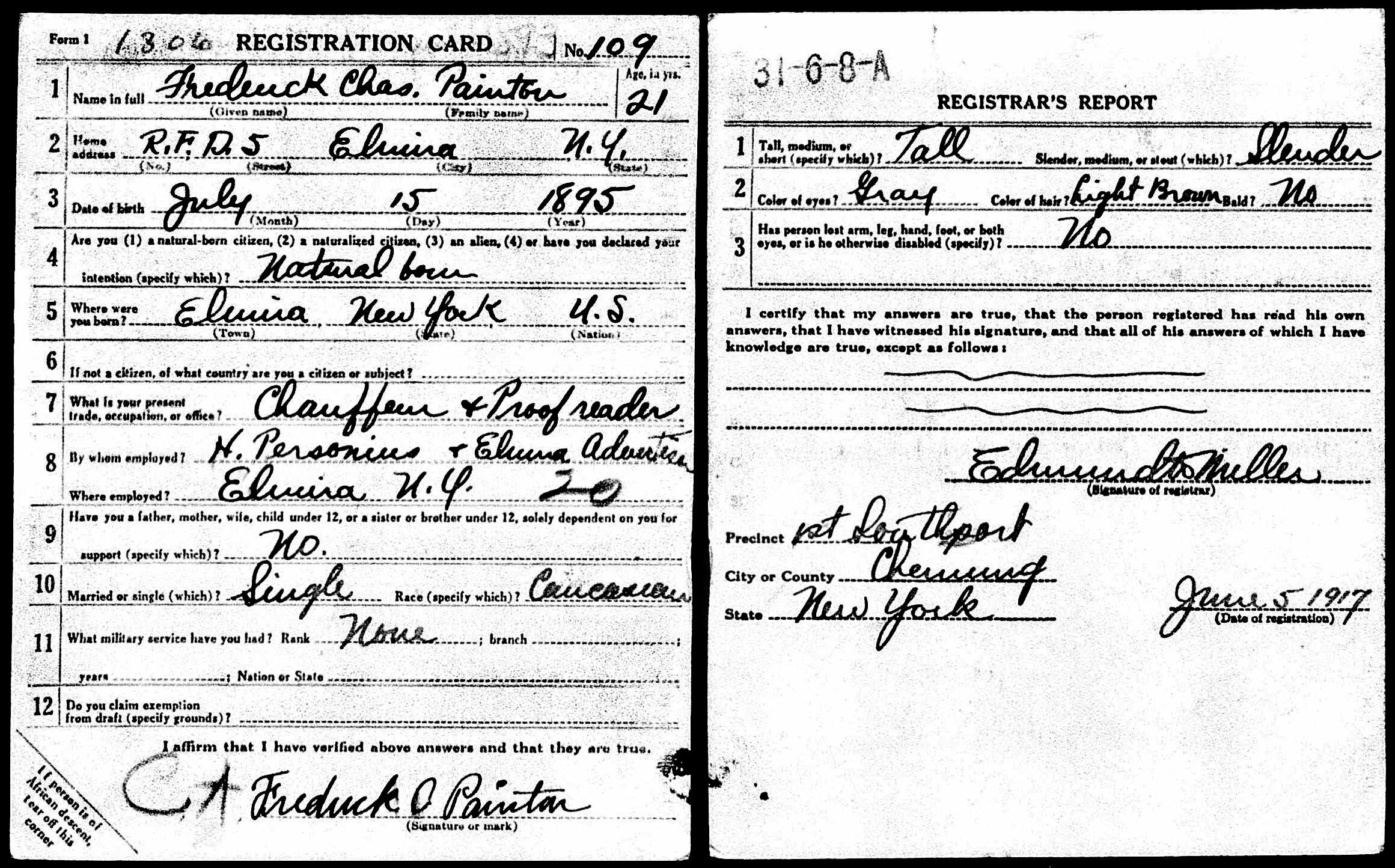

THIS month we’re featuring Frederick C. Painton’s letters he wrote home while serving with the American Expeditionary Forces in WWI. Portions of these letters were published in his hometown paper, The Elmira Star-Gazette of Elmira, New York. Before the war young Fred Painton had been doing various jobs at the Elmira Advertiser as well as being a part-time chauffeur. He was eager to get into the scrap, but was continually turned down because of a slight heart affliction and was not accepted in the draft without an argument. He was so eager to go that he prevailed upon the draft board to permit him to report ahead of his time. Painton left Elmira in December 1917 with the third contingent of the county draft for Camp Dix but was again rejected. He was eventually transferred to the aviation camp at Kelly Field as a chauffeur, and in a few weeks’ time was on his way to England in the transport service with an aviation section, where he landed at the end of January 1918 as part of the 229th Aero Supply Squadron. He was transferred to the 655 Aero Squadron in France shortly thereafter and then to the 496th and eventually attached to the staff of The Stars and Stripes just before the end of the war and stayed on with the occupying forces.

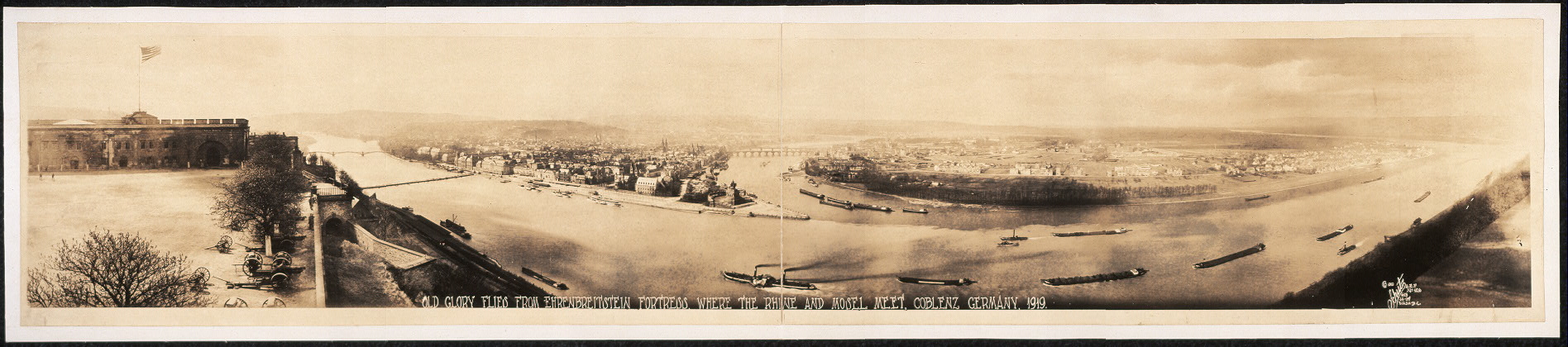

A PANARAMA. Old Glory flies over Ehrenbreitstein fortress looking down on Coblentz, lying peacefully on the juncture of the Rhine and Moselle. Germany 1919.

SERGEANT FRED PAINTON WRITES OF THE AMERICAN OCCUPATION OF COBLENTZ ON THE RHINE

Elmira Star-Gazette, Elmira, New York • 24 January 1919

Elmiran Sends Interesting Description of Chief City in American Sector and Portrays Feeling of the Doughboys When They Show That Kaiser Had the Wrong “Dope.”

Sergeant Frederick C. Painton, former Elmira newspaperman, writes an interesting account of the American army’s crossing of the River Rhine and the occupation of Coblentz. the chief city in the American sector of occupation. Sergeant Painton is now attached to “The Stars and Stripes,†the official paper of the American soldiers in France and is afforded an excellent opportunity to see the things which he describes.

He writes:

“Coblentz, Germany,

“Dec. 13, 1918.

“Today, in a very quiet undramatic marched into Coblentz, the chief and by far largest city included in the territory of occupation. Facing me not fifty yards away is the historic and much sung Rhine, not the German Rhine in our sector, but the American Rhine for the time being. By nightfall the streets swarmed with doughboys. To them came no emotion, this was an everyday job: the Argonne. Chateau Thierry, it was all the same. To the list of tiny unknown French villages, whose names later on were blazed across the papers through the deeds of the A.E.F. is now added that of Coblentz. To those who have never toured Europe. Coblentz is as much of a secret as is La Ferte.

“As Coblentz has been made the headquarters of the 3rd Army and everything of importance centers here, it would not go amiss to give a brief description. Coblentz, with Treves or Trier as the Germans call it, rate as two of the oldest cities in Germany, dating back to the time of Caesar. Although situated at the junction of the Rhine and Moselle, it has never grown much in population. In the Thirty Years War Coblentz was, in turn, besieged and garrisoned by the Swedes, French and Prussians.

“Slipping quickly to the era of Napoleon we find it, after Valmy, made the capital of the new French province of Meurthe et Moselle. It is thus that we can account for the dual names that are horn by all the towns rivers and departments. They have, after Waterloo, been all Germanized. Now, for the first time in over a hundred years, a foreign flag Old Glory, now flies from the City Hall and also from the Ehrenbreitstein, the fortress guarding Coblentz. Does this not give one a feeling of passionate pride in our country?

“I can not resist the temptation to describe for you the Ebrenbreitstein as it looks at the moment perched high on the rugged cliffs on the opposite bank of the Rhine. As I look out the window, the sun, which shines today for the first time in weeks, sets off this monstrous fortress in all its grim and powerful lines. On its highest tower, gently waving in the springlike breeze is “Old Glory.” flaunting in the Kaiser’s face a refutation of his remark that “The Americans will take no important part in this war as they will arrive too late.” We were late, but American speed brought the train in on time.

“Ehrenbreitstein—the name is reminiscent of three balls—has been called and rightly “The Gibraltar of the Rhine.” It was commenced about the time that Napoleon made his exit from the European stage and has been strengthened and improved from year to year as new modes of killing came into vogue. In a way it resembles Verdun, in that it has been hollowed out of the rock. The huge underground chambers will easily billet one hundred men. Monstrous supply rooms occupy the base and by means of spiral stair cases one finally rises to the height of 385 feel and gazes from the cement battlements down on the fair city of Coblentz, lying peacefully on the juncture of the Rhine and Moselle. On clear days one can see Andernach lying further down the Rhine. Up to the time we took possession of the fortress, no foreign soldiers had ever made its will resound with the tread of their footsteps. Now the case is reversed: No German soldiers are allowed inside.

“The city proper lies on the peninsula formed by the juncture of the Rhine and the Moselle. We were much impressed with the civic upbuilding. Each building and private residence were beautiful examples of German architecture and everything was scrupulously neat and clean. The city is laid out very beautifully, with long gardens and promenades running along the banks of the Rhine. Being on that great inland waterway, there is considerable business done in cargo carrying.

“It is rather amusing to run into a newcomer and have him ask eagerly, “Is that there river the Rhine” Upon receiving an affirmative answer, he usually stares long and thoughtfully at it and then with a smile and shake of the shoulders, remark: “Well, that’s sompen to tell the folks at home, by Gosh. I saw their old German Rhine.â€

“You can well imagine our thoughts when, as we stood on the now historic pontoon bridge, about ten o’clock at night, we heard the sweet strains of “Taps†wafted over the swift flowing waters beneath. That we would eventually stand here none of us had any doubts, but who would have thought a few short months ago that the curtain would have been rung down so quickly?

“Today is the 14th of December, a day that will go down in the annals of historv as the day on which our olive drab columns crossed the Rhine to finish occupying our area. We were all up before daybreak, eagerly awaiting the moment when the advance would be sounded. The streets were crowded with the boys of the gallant First. As the dim gray crept across the sky announcing the approach of another dismal, rainy day. the brief command. “Forward March” was given to the leading battalion and the great moment had arrived. Who can say what emotions pierced our breast as battalion after battalion swung into line and the boards began to rattle with the impress of hundreds of steel shod boots? Who can say that we had not received our reward for all the hardships endured as we watched the grim, gaily painted guns go thundering over the bridge quaking beneath their weight? What could we think when we remembered that the remnant of Germany’s fighting machine were slinking away a few short hours ahead of these boys, whose deeds at Monfaucon, Cantigny and Soisson will live forever in the memories of all Americans? All felt the same desire to yell with joy, toss their caps, anything to give vent to their superexuberant spirits brought on by witnessing such a show of a nation’s power as was this. Further up on another bridge of more substantial construction, the lads of the famous second were also taking their place in line. Hundreds of the civilian population left their beds to witness this great event. To those who took stock in Kaiser Wilhelm’s statement that aside from two or three regular divisions, there were no American troops in France, this sight must have been well nigh incredible. Can you wonder that, instead of being angry at having to remain a few months longer, we are intensely proud?”

- Download clipping (24 January 1919, Elmira Star-Gazette)

- Download full page (24 January 1919, Elmira Star-Gazette)

A few weeks later, The Star-Gazette reported that Sergeant Painton was to be shipped home after suffering injuries from gas attack in the St. Mihiel Drive.

SERG. PAINTON ORDERED HOME SUFFERING FROM GAS EFFECTS

Elmira Star-Gazette, Elmira, New York • 18 February 1919

Elmira Soldier Collapses Several Months After Having Been Gassed in St. Mihiel Drive—Has Been Attached To Staff of the Stars and Stripes.

Sergeant Frederick C. Painton, son of Mr. and Mrs. George Painton, former Elmira newspaperman, whose interesting letters from France have been widely read, is enroute home, suffering from the effects of gas, which he received during the St. Mihiel drive by General Pershing’s troops. Painton has lately been attached to the staff of The Stars and Stripes and was having a most interesting experience as a reporter with the American Army of Occupation when he suddenly collapsed and was forced to give up his work.

He writes: “A year ago today I landed in Glasgow, England, and now, on the anniversary, I find myself scrapped, war’s cast-off and en-route home.” Painton was gassed several months ago. and at the time paid no attention to the matter. He says “now I am getting the real effects, my stomach is gone, my nerves are gone, and, as you know, I already had a bad heart, so here I am feeling as bad as the Kaiser. I expect to sail in about a week and should be in Elmira by the first of March.”

Painton was evacuated from Coblentz on the Rhine and was forced to leave all effects in his trunk at Paris. He says he fears he will have to spend his first month home in bed, but he hopes to soon be tearing off copy for local papers before very long.

Painton was thrown by the concussion of a shell while at Troyon, during the St. Mihiel drive, and believes that he suffered an injury to his side. Because of the condition of his nerves, he is unable to sleep at times without the aid of an opiate. The former reporter declares he dislikes very much to leave at this time, because he was having a wonderful experience with the American Army. However, he looks forward to the trip home as a tonic, although greatly disappointed because he must leave his trunk full of war souvenirs behind. He hopes to have a friend take care of it for him until he can have it sent home.

Painton was a reporter in Elmira at the time the United States entered the war. He was eager to get into the scrap, but was continually turned down because of a slight heart affliction. He was not accepted in the draft without an argument, and so eager was he to go that he prevailed upon the draft board to permit him to report ahead of his time. He was again rejected at Camp Dix, but finally was allowed to go to Kelly Field as a chauffeur, and in a few weeks’ time was on his way across in the transport service with an aviation section.

Finally an opportunity came to him, after the armistice was signed, to become attached to The Stars and Stripes, the official publication of the American soldiers, published in Paris. His articles, which have appeared in the local papers, have been widely read.

- Download clipping (18 February 1919, Elmira Star-Gazette)

- Download full page (18 February 1919, Elmira Star-Gazette)

Frederick C. Painton’s letters he wrote home while serving with the American Expeditionary Forces in WWI. Portions of these letters were published in his hometown paper, The Elmira Star-Gazette of Elmira, New York. Before the war young Fred Painton had been doing various jobs at the Elmira Advertiser as well as being a part-time chauffeur. He was eager to get into the scrap, but was continually turned down because of a slight heart affliction and was not accepted in the draft without an argument. He was so eager to go that he prevailed upon the draft board to permit him to report ahead of his time. Painton left Elmira in December 1917 with the third contingent of the county draft for Camp Dix but was again rejected. He was eventually transferred to the aviation camp at Kelly Field as a chauffeur, and in a few weeks’ time was on his way to England in the transport service with an aviation section, where he landed at the end of January 1918 as part of the 229th Aero Supply Squadron. He was transferred to the 655 Aero Squadron in France shortly thereafter and then to the 496th and eventually attached to the staff of The Stars and Stripes just before the end of the war and stayed on with the occupying forces.

Frederick C. Painton’s letters he wrote home while serving with the American Expeditionary Forces in WWI. Portions of these letters were published in his hometown paper, The Elmira Star-Gazette of Elmira, New York. Before the war young Fred Painton had been doing various jobs at the Elmira Advertiser as well as being a part-time chauffeur. He was eager to get into the scrap, but was continually turned down because of a slight heart affliction and was not accepted in the draft without an argument. He was so eager to go that he prevailed upon the draft board to permit him to report ahead of his time. Painton left Elmira in December 1917 with the third contingent of the county draft for Camp Dix but was again rejected. He was eventually transferred to the aviation camp at Kelly Field as a chauffeur, and in a few weeks’ time was on his way to England in the transport service with an aviation section, where he landed at the end of January 1918 as part of the 229th Aero Supply Squadron. He was transferred to the 655 Aero Squadron in France shortly thereafter and then to the 496th and eventually attached to the staff of The Stars and Stripes just before the end of the war and stayed on with the occupying forces.