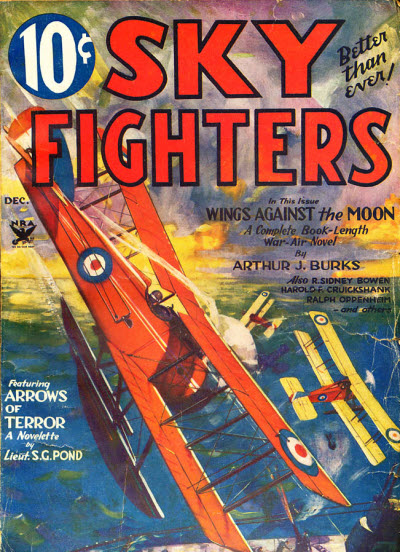

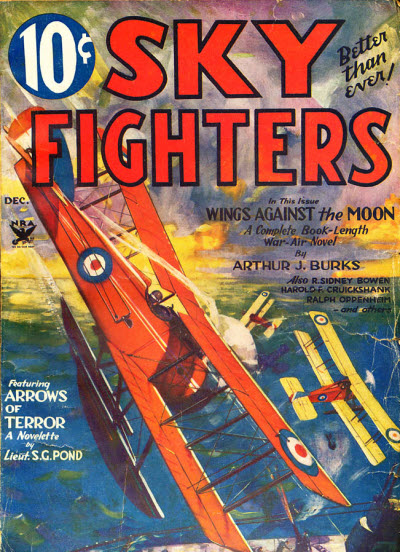

FROM the pages of the December 1933 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

Flying Comfort

by Robert Sidney Bowen (Sky Fighters, December 1933)

SO! SOUND asleep, the lot of you, eh? Well, my pin-feathered buzzards, that suits me just fine. In fact, it’s perfect. It gives me an idea of what to chin about this time. For a week I’ve been lying awake nights, tearing out my hair, wondering what I could talk about that would be close to your dear little hearts, and which you’d all understand.

Well, you yourselves gave me the idea. What subject could you better understand than one dealing with comfort?

And so, I will proceed to raise my usually calm and soothing voice above the stentorian chorus of snores, and bellow at you about the art of flying comfort.

We Were Comfortable

Though it breaks my heart to reveal the truth, my conscience forces me to draw aside the veil and show just how comfortable we baldheaded eagles were in the days when the word German was something that made you jump and jump fast.

As your big sisters have probably told you, wartime airdromes were never located in the middle of No-Man’s-Land. In fact, they were usually fifteen to twenty miles behind the lines. Such being the case, we had no fears of waking up and finding German infantrymen plowing through the room. And so, we could add the old home sweet home touch to our abodes and know that it would all still be there when we got back from a gallant patrol.

Sure! We had hutments to live in, blankets and clean sheets. A mess lounge to get plastered in, too. True, the furniture was not all mahogany or birdseye maple. However, it didn’t fall apart, much. And most important of all, my dears, the grub was good. It wasn’t dropped in the mud, and it was cooked (by a cook) in a real stove. There was usually some sort of a piano that worked. And, of course, the ever-present phonograph.

Now, before I mislead you too much, let me explain that the pilots more or less enjoyed solid comfort only as compared to the men holding the line.

I COULD name lots of places that are heaven compared to a wartime airdrome, and not even exaggerate. So, just keep it in your think-box that I’m speaking of flying comfort as compared to infantry or artillery comfort.

Visiting the Neighbors

And so, we were able to install all the little things that helped to make life enjoyable when not in the air. Usually there was a village near-by, with at least one worthwhile estaminet where we could go between patrols or any time when we were off duty. Also, if the field was big enough, more than one squadron used it, with the result that you had neighbors to visit, etc.

IN OTHER words, while an airman was on the ground, it really was a pretty good war.

In the air, though, it was different. And naturally so, because for us, that’s where the war was—in the air.

But here’s the point—we didn’t confine all our efforts for comfort to the time when we were on the ground. We took it along with us when we went up, providing, of course, it didn’t interfere with air scrapping.

That, of course, was the one essential thing to think about. And as a result, the comfort that we tried to get in the air was in reality a type of comfort that actually helped air performance.

Just a Few Examples

For a few examples of what I mean, unbutton your ears to these.

Straight flying—ordinary patroling between two points—is about the most monotonous thing east or west of the Seven Seas. There’s nothing to do but sit and fly, and then sit and fly some more. On a smooth day your legs and arms and neck get so doggone cramped, that you suddenly’ find yourself praying aloud for a flight of enemy ships to drop down on you.

True, you’ve got to keep your eyes open, to spot said enemy ships ahead of time.

And also you’ve got to keep on the alert so that you won’t slide out of formation position. But after awhile at the Front that sort of thing becomes almost mechanical. Like a sixth sense, you might say.

To permit themselves the opportunity to relax, some of the boys had headrests fitted to the top of the fuselage just back of the cockpit. The headrest was just a leather pad streamlined into the top of the fuselage. On some ships, the S.E.5, for example, the headrest was already there. And to show you how queer war pilots can be, some of the guys had the headrest of their S.E.5

taken off, because they said it cramped their necks! (See Fig. A.)

Every Little Thing Counts

ANOTHER little thing that we added for comfort’s sake, was a little box fitted to a fuselage crossbrace inside the cockpit. In ships that had a Lewis gun mounted on the top center section, the box was already there. That is, there were two boxes in which you carried a couple of spare Lewis drums of ammo. So you simply carried one extra drum—and the other was your box.

What for? Why, to keep things in, dummy. What things? Well—that depended upon the pilot’s likes and dislikes. Me, I used to slip a couple of bars of chocolate in, a cloth with which to wipe oil spatterings off my goggles, a couple of nips of this and that in a flask (in case of a cold, you understand), a picture of the current girl friend to gaze at if I felt lonely, a box of matches, and at least one deck of cigarettes.

Cigarettes?

Ah, I knew darn well that buzzard over there in the corner wasn’t asleep! Sure, we carried cigarettes. Why not? No, not to smoke while we were in the air. Nix! Can do, as a stunt. But didn’t as a regular practice.

No, the idea was, in case we got forced down and taken prisoner. Yes, sir, we were that way. Made sure of our comfort—in case. And if you think that’s a funny idea, go get yourself taken prisoner some day, and find out how many smokes the enemy gives you! Yeah, you’!I learn!

If We Were Captured

AND speaking of being taken prisoner. Some of the lads used to sew a small compass and a map or two in the lining of their flying suits. I once heard of a case where that little stunt was the means of a bird escaping an enemy prison camp. Well, all I can say is, that guy sure was lucky, and then some!

In the first place, the enemy wasn’t as dumb as the newspapers try to make them out to be. They knew a few things about fighting a war just as we did.

And searching a captured prisoner for anything that might help or hinder him was something that the Germans did nothing else but. However, for argument’s sake, let’s say that the searching officer was blind in one eye, couldn’t see out of the other, and both hands were cut off. Well, the hero goes to a prison camp, tells the guard to look the other way, and sets off for home. He uses the compass and starts south. Soon it gets darn cold and he meets an Eskimo. Heavens, he’s been walking all these weeks in the opposite direction.

And why? Because that little compass sewed in his flying suit was long ago sent haywire by the metal and ignition system of his engine.

But to get back to that box—comfort box, you could call it—I’ve told you a few of the things I used to lug along. Other guys used to carry other things. One chap, for instance, used to take along pen, paper and envelopes. Sure! Do his letter writing while waiting for action.

No Identification!

However, that was just an unusual stunt. Don’t get the idea that it was general practice. And also don’t get the idea that the box was big enough to hold a couple of spare props and

a tire maybe. And also, take it from me, you did not carry anything that would be valuable to the enemy if captured. I carried the girl friend’s picture, but I didn’t carry any of her letters to me.

No, smart guy, not because I was afraid the ship would catch fire! Simply because they were identification, and might contain information of something seemingly unimportant, but perhaps most important when pieced together with what the enemy might already know.

In other words, we carried in the box, or on our person, nothing that would divulge information to the enemy.

I Call It Laziness

MAYBE you’d call this next item comfort, but I call it just plumb laziness. It was a flight leader’s trick. As you know, a flight leader has to keep his eye on the ships back of him, just as much as the other lads have to keep their eyes on him.

So this bird, in order to save wear and tear on his neck, got hold of a piece of looking glass and fastened it near the top of his right rear center section strut. Yup, a rear view mirror for airplanes. And believe it or not, the thing worked swell—so he claimed! (See Fig. B.)

Another idea for comfort, and a thing that was mighty useful in a dog scrap, was a pair of shoulder straps fastened to the sides of the cockpit seat. (See Fig. C.) As you know, every ship had the regular safety belt that fastened about your waist. That was okay for level flight, but should you get hung in a loop, gravity would start to slide you out and pull your feet off the rudder bar.

So we installed two straps; one that came up the back and over the right shoulder and down the left side of the seat, and the other came up over the left shoulder, crossed the other at your chest, and down to the right side of the seat. Thus you were held back by the safety belt, and held down on your seat by the double straps. Naturally, snap fastenings were used, in case you had to get clear fast—like in thr event of a forced landing.

It’s All How You Look At It

Yup, our motto was, comfort east or west of No-Man’s-Land. Of course, it wasn’t like home. We did get our feet wet now and then. However, in case the Grim Reaper ever reached out for us, we kind of planned it so we’d at least die on a full stomach. For the lads on the ground shoving about the trenches, such was not the case. They had to take it on the chin day and night.

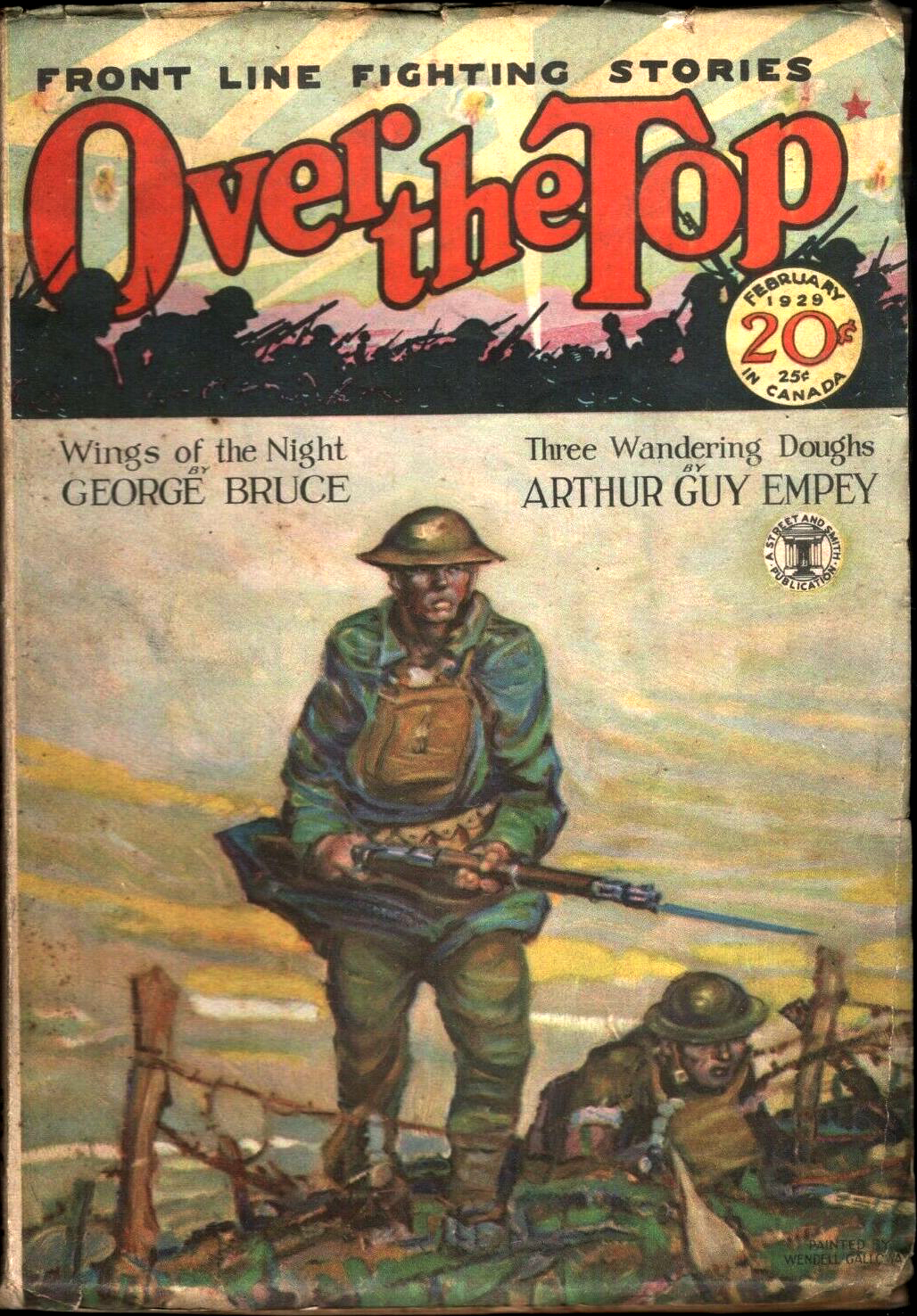

Yet, after all, it’s the way you look at it. The doughboy in the trench looks up at the aviator and says, “Cripes, that damn fool up there with nothing to hang onto!†And the pilot looks down and says, “Cripes, that damn fool down there with nothing but mud to sit on!†And, so what? As far as I’m concerned, it’s, so long!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

one of the few stories from Fred Denton Moon. Moon was born in Athens, Georgia in 1905 and was a freelance writer. A former staff member of The Atlanta Journal Sunday Magazine, he was the first editor of the Journal’s wire photo service as well as former city editor of the Journal. He was member of Sigma Delta Chi and a retired member of the Georgia Department of Labor.

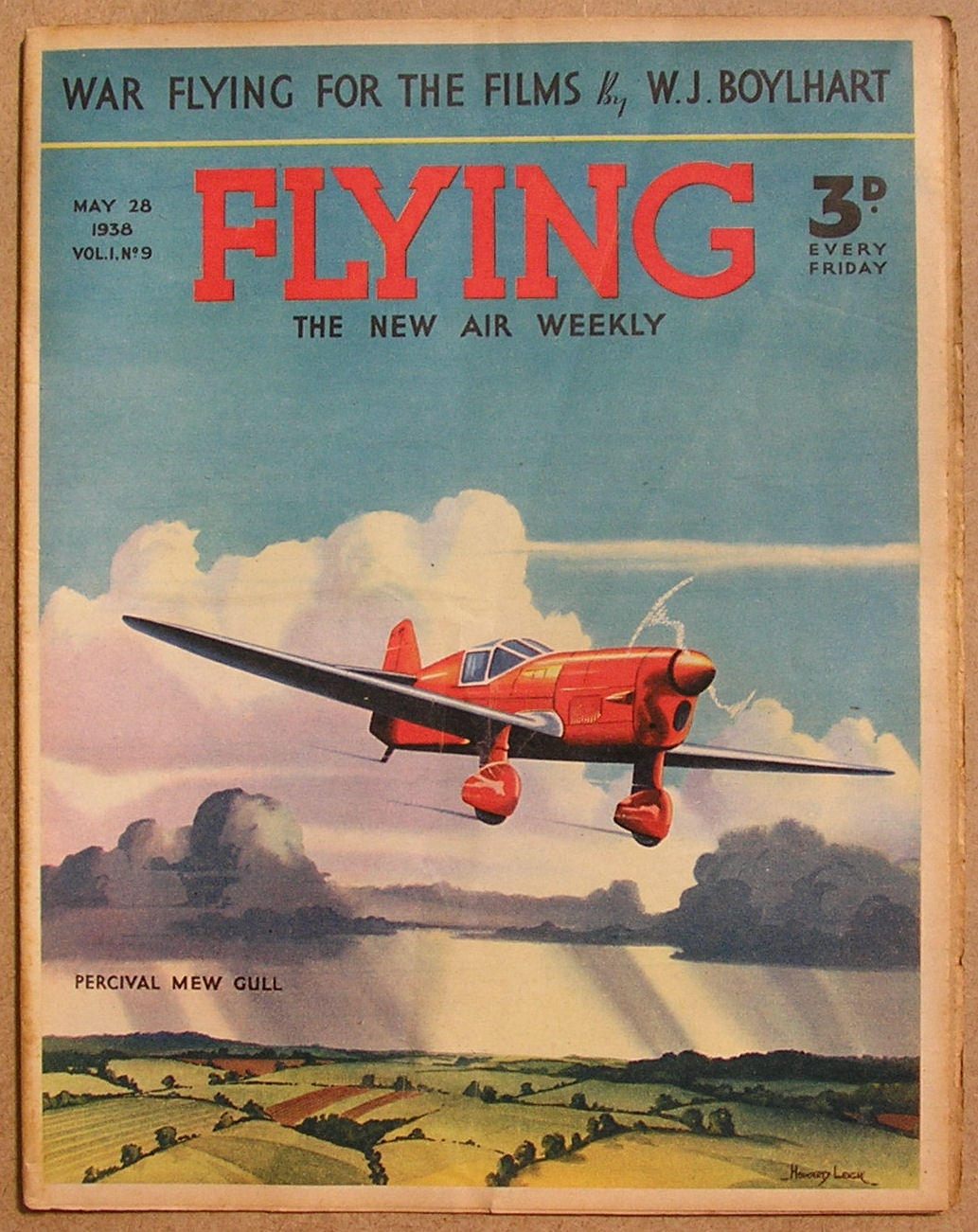

one of the few stories from Fred Denton Moon. Moon was born in Athens, Georgia in 1905 and was a freelance writer. A former staff member of The Atlanta Journal Sunday Magazine, he was the first editor of the Journal’s wire photo service as well as former city editor of the Journal. He was member of Sigma Delta Chi and a retired member of the Georgia Department of Labor.  weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

weekly paper of all things aviation, started up in England in 1938, amongst the articles and stories and photo features was an illustrative feature called “Heroes of the Air.” It was a full page illustration by S. Drigin of the events surrounding how the pictured Ace got their Victoria Cross along with a brief explanatory note.

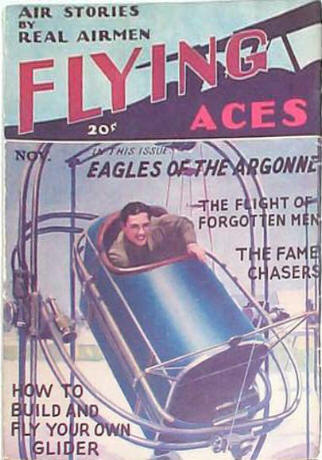

a story by Franklin M. Ritchie. Ritchie only wrote aviation yarns and his entire output—roughly three dozen stories—was between 1927 and 1930, but Ritchie was not your typical pulp author.

a story by Franklin M. Ritchie. Ritchie only wrote aviation yarns and his entire output—roughly three dozen stories—was between 1927 and 1930, but Ritchie was not your typical pulp author.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

a story from

a story from

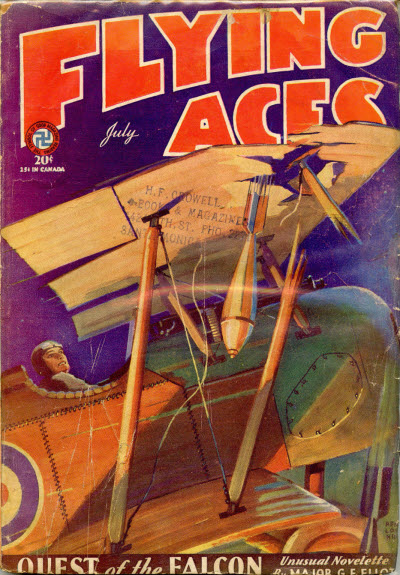

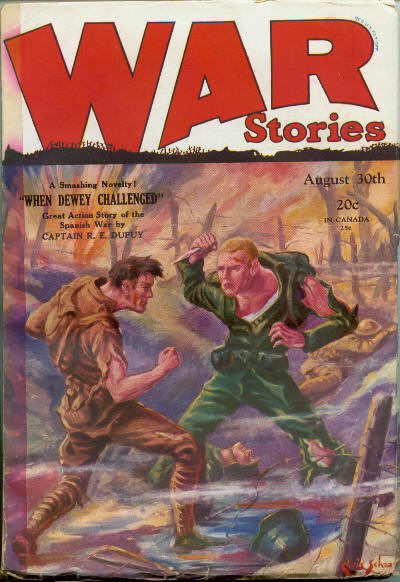

exciting adventure in those Hell-skies with Alexis Rossoff’s Hell-Cat Squadron! The adventures of the Hell-Cat Brood ran in War Birds, War Stories and Flying Aces. The Seventy-Seventh Squadron had a reputation of being short on technique and long on defying every regulation in the book. The squadron was the cause of many gray hairs on the pates of the star-spangled ones back in G.H.Q. They flew their merry way like nobody’s business, and played hell with any Jerry who tried to dispute their intention of going places. This bunch of cloud-hopping war birds were known from one end of the Western front to the other as the “Hell-cats”—and sometimes the “Unholy Dozen!”

exciting adventure in those Hell-skies with Alexis Rossoff’s Hell-Cat Squadron! The adventures of the Hell-Cat Brood ran in War Birds, War Stories and Flying Aces. The Seventy-Seventh Squadron had a reputation of being short on technique and long on defying every regulation in the book. The squadron was the cause of many gray hairs on the pates of the star-spangled ones back in G.H.Q. They flew their merry way like nobody’s business, and played hell with any Jerry who tried to dispute their intention of going places. This bunch of cloud-hopping war birds were known from one end of the Western front to the other as the “Hell-cats”—and sometimes the “Unholy Dozen!”