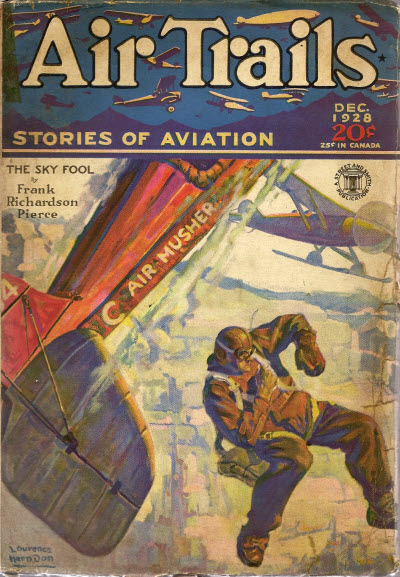

Frank Richardson Pierce is  probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

Pierce was born in 1881 in Greenfield, Massachusetts but raised on the west coast. A graduate of the University of Washington, he served for a year and a half in the US Navy as a boatswain’s mate and worked for the city of Seattle as a clerk stenographer. He began writing travel articles about the northwest for various motorcycle trade journals and later progressed to short story writing.

Pierce draws upon his knowledge of the Pacific Northwest from his reported fourteen different motorcycle trips to and through the Alaska territory for his story of rival news-reels services covering the first woman to fly over the North Pole. The story features Rusty Wade, Pierce’s rough and tumble red-headed pilot for hire looking for his big financial break.

A story of daring pilots and news-reel men on the far sky trails of the Northland.

And as a bonus, here’s an article from Mr. Pierce’s former home town paper, The San Bernardino Daily Sun, about his successful career in the pulps!

Graduate of Redlands School 25 Years Ago Now Writes Scores of Stories Yearly for Magazines

Thousands of Readers Know Frank Richardson Pierce Under Two Names; Spends Week-End Visiting Foothill City Home

By MAURICE S. SULLIVAN

San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, CA • 10 May 1932

When Frank Richardson Pierce graduated from Redlands’ old Kingsbury school, about 25 years ago, he didn’t know that some day he should have two names.

Thousands of readers of the so-called pulps—magazines printed on rough paper—know a writer named Seth Ranger, and eagerly follow his stories of the frontier days, the logging country, Alaska and the Orient. Some of them also know a writer named Frank Richardson Pierce, but the latter has his own distinct following, who watch for his stories Just as do the devotees of Seth Ranger.

Frank Richardson Pierce and Seth Ranger are the same writer. He lives now in Seattle, but he spent his boyhood in Redlands. Whenever—in one of his stories—he needs a small city setting, or a town just over the mountains from the desert, his mind goes back to the Redlands of his youth and under another name Redlands goes into the story.

He spent the last week-end here, at the home of his father, Martin F. Pierce, 24 East Fern avenue. He was taking a brief vacation after having completed “Timber War.”

Frank Pierce is one of those talented persons who turn out stories for the pulps In a seemingly endless stream, while at the same time producing an occasional yarn for the slicks—smooth paper magazines. Howard Marsh, a Redlands resident; Fred McIsaac and H. Redford Jones are others who have the faculty.

To those persons who spend months trying to fashion a readable story, revising and rewriting, the skill of Mr. Pierce and his co-workers is amazing. In one year this writer sold 121 stories, at the rate of about 10 each month: short stories, novelettes and serials of novel length.

Conversing with Mr. Pierce one learns that this extraordinary success, as in the case of most writers, has a basis of hard work and study. He had to learn his trade by practice and by examining the technique of those who were publishing their output.

“The first nine or 10 stories I wrote didn’t click,” said Mr. Pierce. “Then I received a lucky break.

“I had been in the naval reserve during the war, so that I know a good deal of naval procedure and the language of the navy. One day I picked up a magazine In which there was a sea story with the navy as a setting.

“As I read it, I said to myself that here was something right down my alley, and if that was the kind of thing the editors of that particular magazine wanted, I could write it. I turned out a story and sent It to New York.

“It happened that as the editor of the magazine was reading my manuscript a naval officer, a friend of his, came into the office. The editor tossed the script to this officer and asked him his opinion.

“Men in certain trades and professions are very critical of stories dealing with their crafts, and the writer who tries to draw on his imagination for facts and atmosphere is likely to bring down on his head a storm of derisive letters. But when the naval officer read this story of mine he was pleased.

“It might not have been a particularly good story, but he was reading it with an eye for flaws in detail. When he found the language of the characters was authentic navy talk, and the method of abandoning ship, which I had described, was accurately detailed, he thought It was a great yarn. He told the editor so. The story sold, and I was able to turn out a series of them along the same lines.”

Seattle is a very advantageous place in which to live, for one who writes. To that city come the ships of the Orient, men from far places in the North, returning to civilization. There is a cattle country and a mountain country nearby. Fisheries, canneries, logging camps and timber locales all are available. The city is the home of persons who have lived through the Klondike days of Alaska.

When the writer is balked by some perilous piece of detail or atmosphere, he knows where he can get assistance, if he had made friends with the old-timers.

Mr. Pierce wrote a story in which a character was found frozen stiff squatting on his haunches in front of a fireplace, with his hands extended as if warming them at a blaze.

This scene brought a flood of letters, starting with one from a man who sarcastically averred that a freezing man would relax and fall over; that it was sheer impossibility that he should be frozen in the squatting position.

A loyal fan of Seth Ranger came to his rescue with an even more sarcastic letter. He enclosed a photograph of a man frozen while standing upright, and suggested to the writer that he “show this to that so-and-so who thinks he knows so much.” A Seattle friend of Mr. Pierce settled the matter for him. Jake the Musher, veteran of many trails, not only vouched for the accuracy of the frozen man detail, but also related similar instances out of his vast fund of experiences in the North.

The stumbling writer who fashions a line, then pauses to improve it, would be amazed to see Mr. Pierce at work. He usually makes but one draft of a story, turning it out at high speed, and shooting it, without revision, at the magazine for which it was “slanted.” There was a time, during an illness, when he talked his stories into a dictating machine, and depended upon a typist to transcribe them. It was difficult and discouraging, but because he had to do it, he kept at it until he could dictate as well as he could write.

Writing for the pulps is Mr. Pierce’s livelihood, but he is not content only to do that. He studies meanwhile, constantly striving for improvement; not trying to write literature, because the boundaries of literature are very vague and nobody living can say certainly what of the present day writing shall be called literature 100 years from now; but so long as folk are entertained by what he writes, striving to give them the best in the field.

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back! The men of the Ninth had taken to an aged pooch of doubtful lineage that had wondered into camp. They had named him Rollo and even built him a diminutive Nissen hut in which to rest his weary bone. Sadly, Rollo’s days were coming to an end and it was Phineas who drew the duty of making sure Rollo went West.

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back! The men of the Ninth had taken to an aged pooch of doubtful lineage that had wondered into camp. They had named him Rollo and even built him a diminutive Nissen hut in which to rest his weary bone. Sadly, Rollo’s days were coming to an end and it was Phineas who drew the duty of making sure Rollo went West.

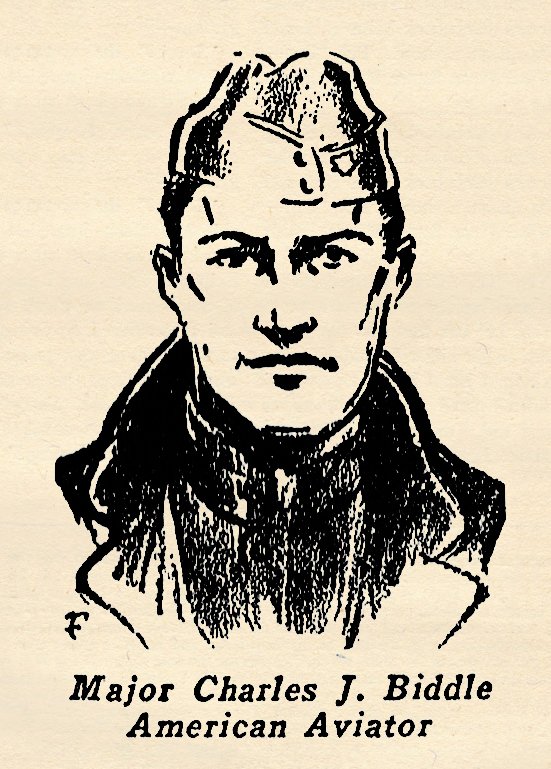

of that small number of American aviators who had actually had front line battle experience when his own country entered the war. Even before there were any indication* of his own country taking part, he sailed for France and enlisted in the French Army, where he was eventually transferred for aviation tralning. When the La Fayette Escadrille was formed, he wan invited to become a member. In that organization he won his commission as a Lieutenant in recognition of his ability and courage.

of that small number of American aviators who had actually had front line battle experience when his own country entered the war. Even before there were any indication* of his own country taking part, he sailed for France and enlisted in the French Army, where he was eventually transferred for aviation tralning. When the La Fayette Escadrille was formed, he wan invited to become a member. In that organization he won his commission as a Lieutenant in recognition of his ability and courage.

probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger—Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.  was born on September 1st, 1895, in Brookline, Massachusetts. He enlisted in the Aviation Section of the U.S. Army Signal Corps in July 1916, and began flight training at the School of Military Aeronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in June the following year.

was born on September 1st, 1895, in Brookline, Massachusetts. He enlisted in the Aviation Section of the U.S. Army Signal Corps in July 1916, and began flight training at the School of Military Aeronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in June the following year.  we have a tale from the anonymous pen of Lt. Frank Johnson—a house pseudonym. Sky Fighters ran a series of stories by Johnson featuring a pilot who who was God’s gift to the Ninth Pursuit Fighter Squadron and although he says he’s a doer and not a talker, he wasn’t to shy to tell them all about it. Which earned him the nickname “Silent” Orth. This time Silent Orth goes after Baron Rapunzel—a Boche Ace who’s already claimed 51 victories—and Orth doesn’t plan to be the 52nd!

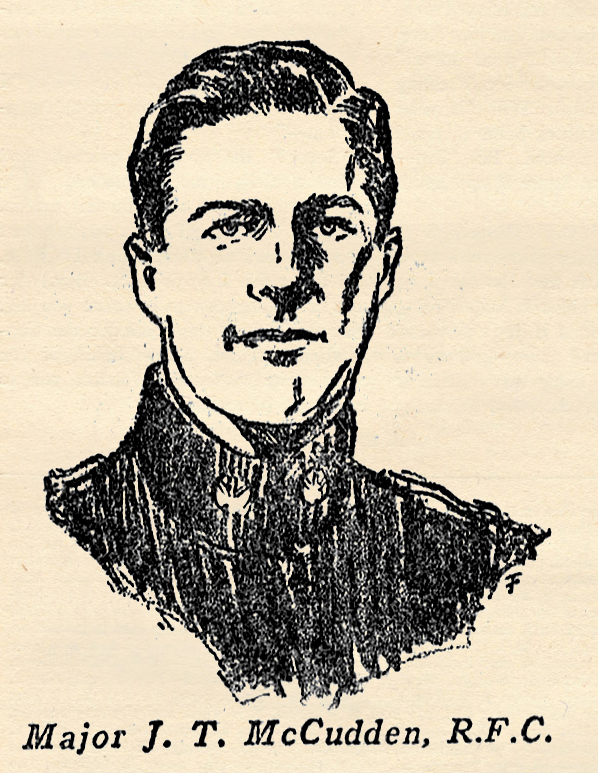

we have a tale from the anonymous pen of Lt. Frank Johnson—a house pseudonym. Sky Fighters ran a series of stories by Johnson featuring a pilot who who was God’s gift to the Ninth Pursuit Fighter Squadron and although he says he’s a doer and not a talker, he wasn’t to shy to tell them all about it. Which earned him the nickname “Silent” Orth. This time Silent Orth goes after Baron Rapunzel—a Boche Ace who’s already claimed 51 victories—and Orth doesn’t plan to be the 52nd!  one of the most modest and unassuming of the great flying aces. When the war began he was an engine mechanic with the then recently formed Royal Flying Corps. After flying training he became a Sergeant pilot, and began, piling up the string of victories which eventually placed him at the top of all the British aces. He was progressively promoted to Lieutenant, Captain and Major, and won every medal possible, including the Victoria Cross.

one of the most modest and unassuming of the great flying aces. When the war began he was an engine mechanic with the then recently formed Royal Flying Corps. After flying training he became a Sergeant pilot, and began, piling up the string of victories which eventually placed him at the top of all the British aces. He was progressively promoted to Lieutenant, Captain and Major, and won every medal possible, including the Victoria Cross.

the Black Mask school of pulpsters, penned a popular series about the vagabond pilots Gales and McGill—free-lances of the air, birdmen of fortune, the wildest brace of adventurers that ever came out of America. They were notorious on the coast, known from Shanghai to Surabaya for a brace of wild, reckless adventurers, ripe at all times for anything short of murder.

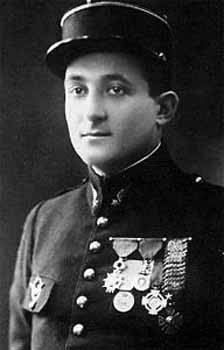

the Black Mask school of pulpsters, penned a popular series about the vagabond pilots Gales and McGill—free-lances of the air, birdmen of fortune, the wildest brace of adventurers that ever came out of America. They were notorious on the coast, known from Shanghai to Surabaya for a brace of wild, reckless adventurers, ripe at all times for anything short of murder. was one of the most famous of the French flying aces. Along with Guynemer, Navarro and Nungesser, he furnished the spectacular flying news that filled the newspapers in the early days of the World War. He was credited with forty-one victories—only the great Guynemer topped him in the list of French aces during his time on the battle front—and awarded the Legion d’Honneur, Medaile Militaire, and Croix de Guerre.

was one of the most famous of the French flying aces. Along with Guynemer, Navarro and Nungesser, he furnished the spectacular flying news that filled the newspapers in the early days of the World War. He was credited with forty-one victories—only the great Guynemer topped him in the list of French aces during his time on the battle front—and awarded the Legion d’Honneur, Medaile Militaire, and Croix de Guerre.