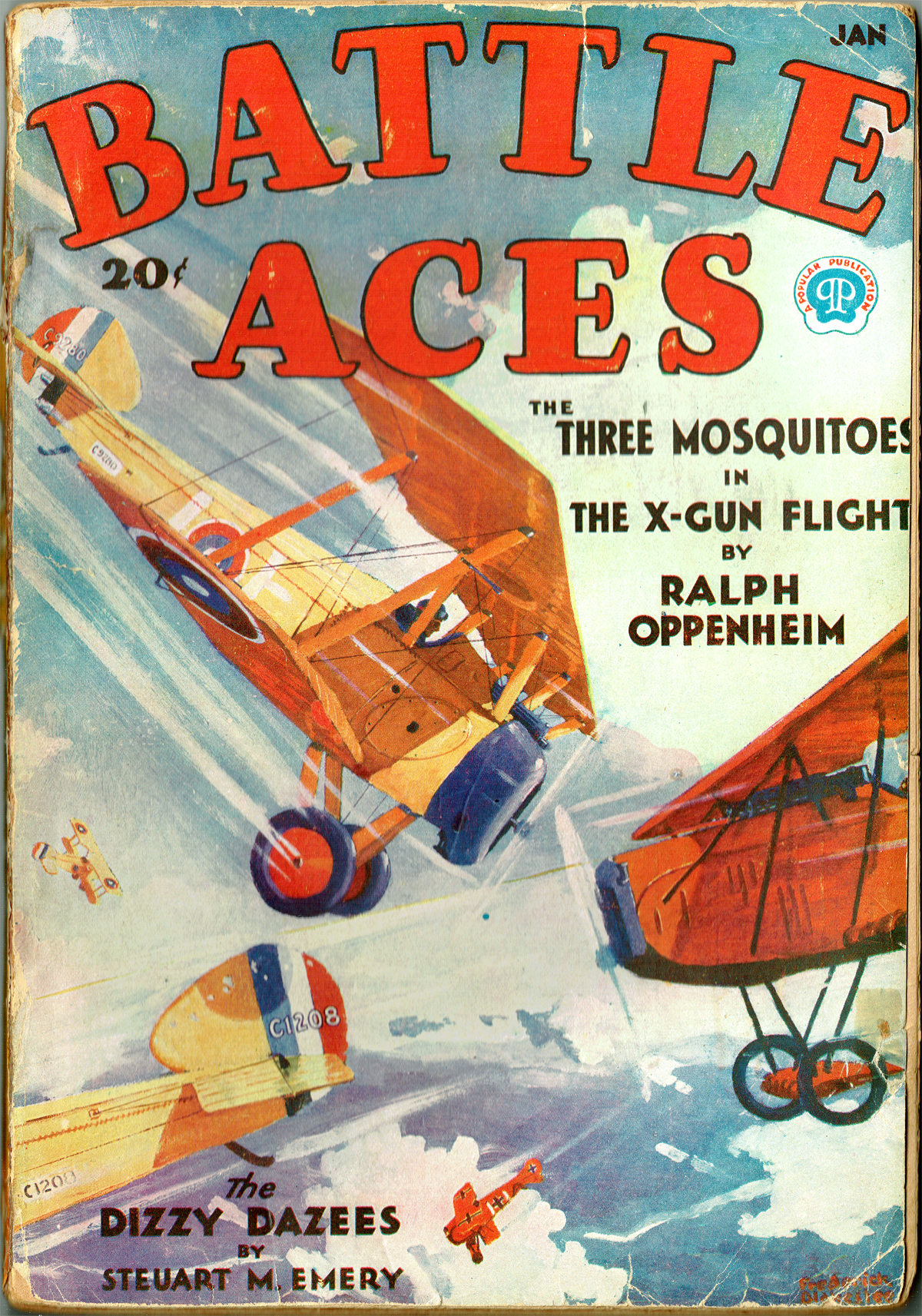

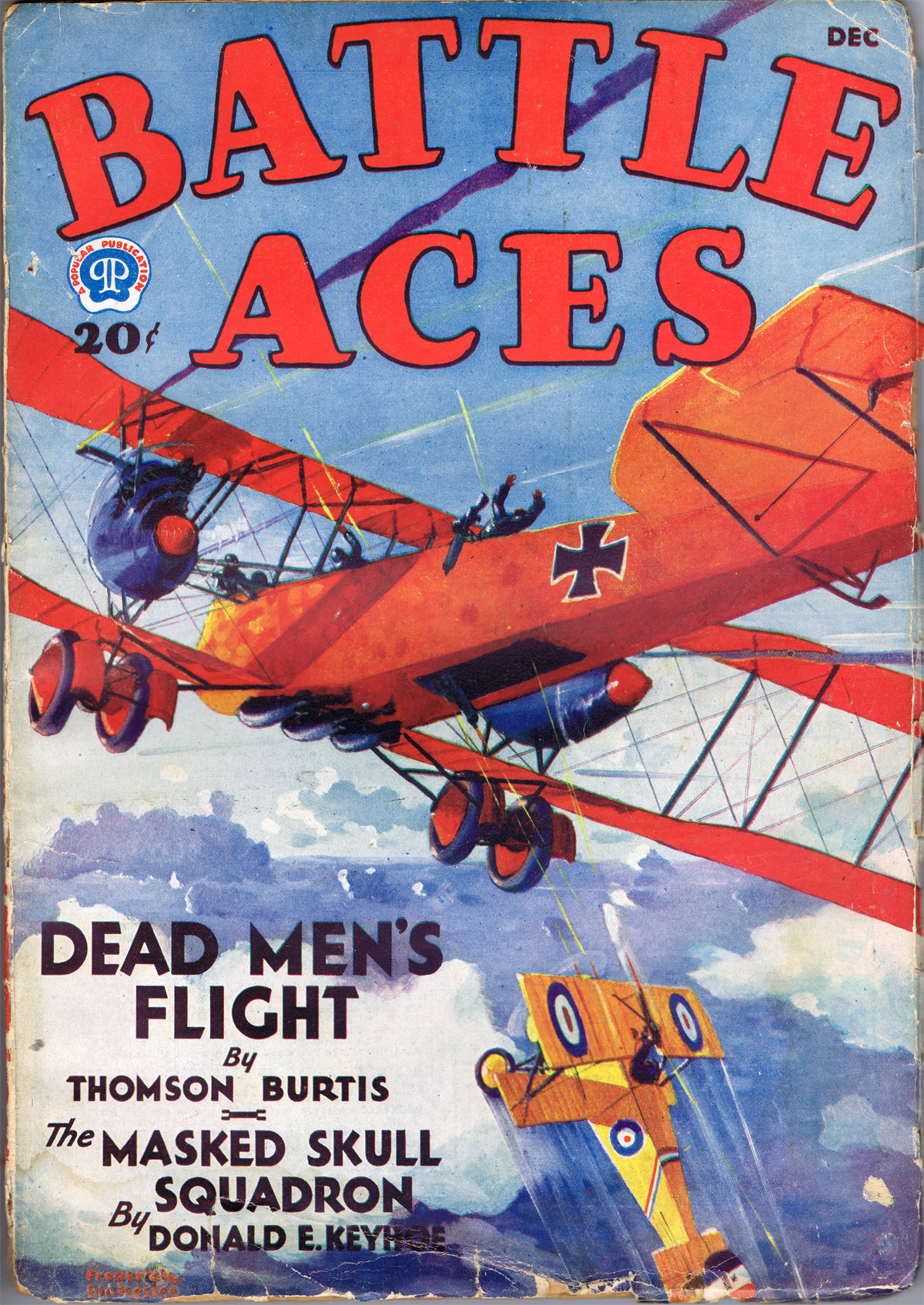

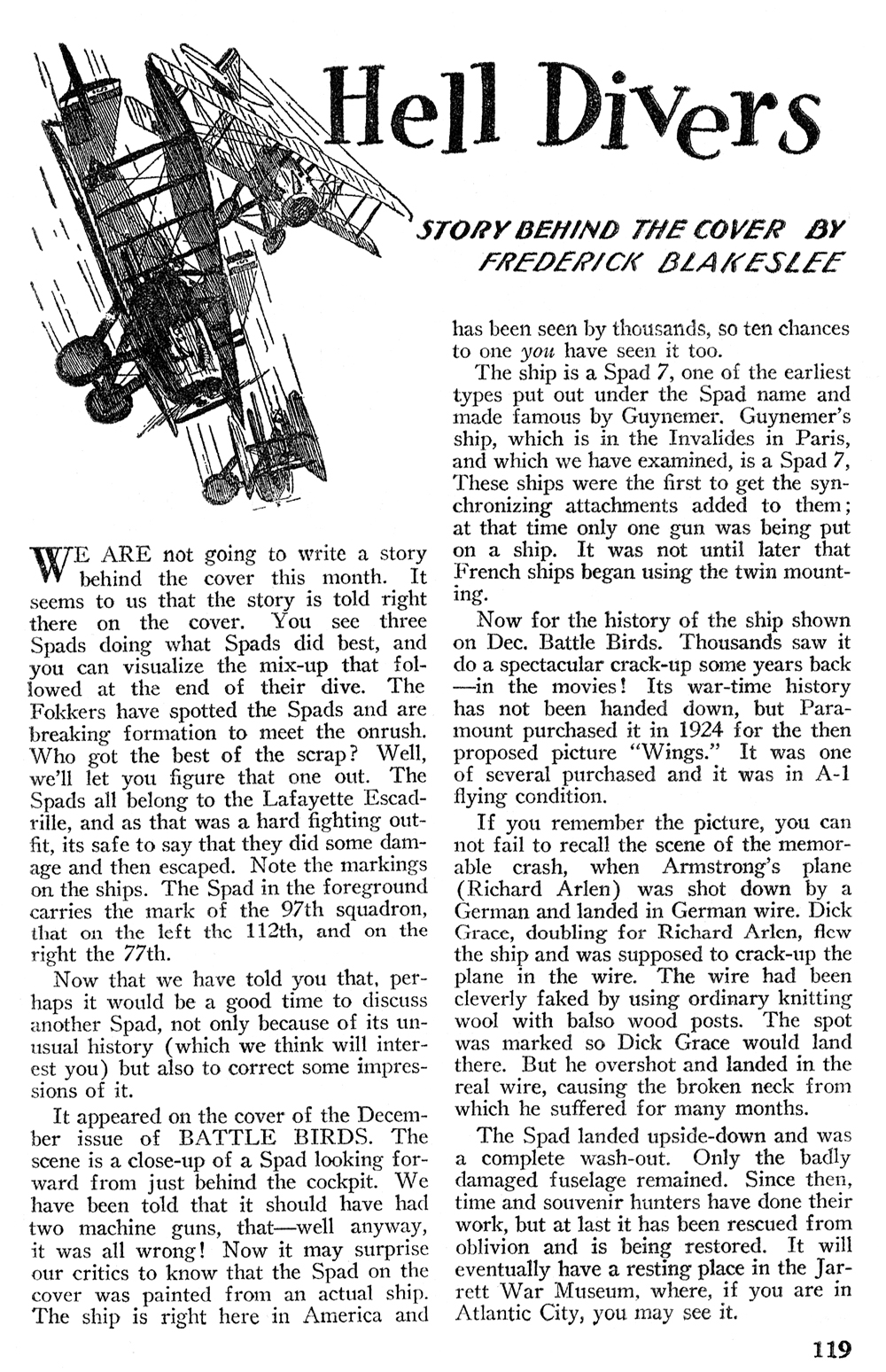

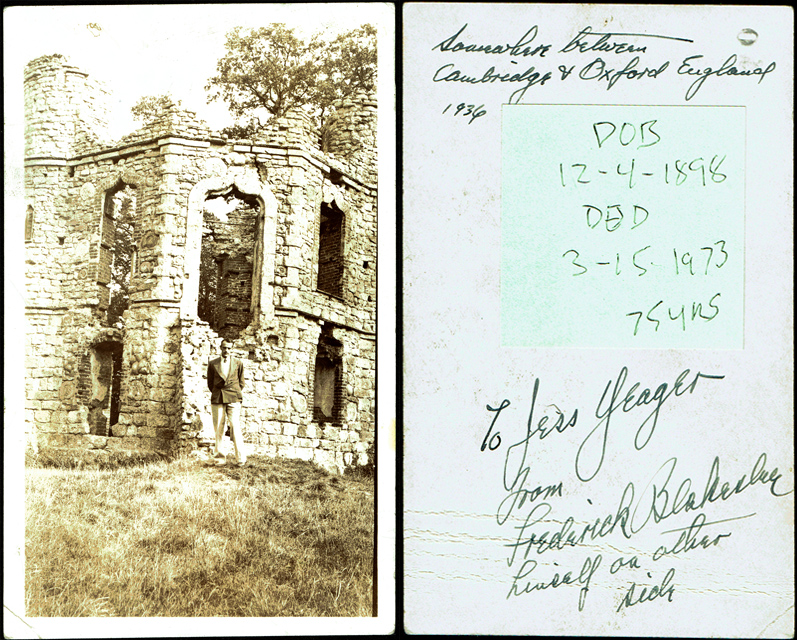

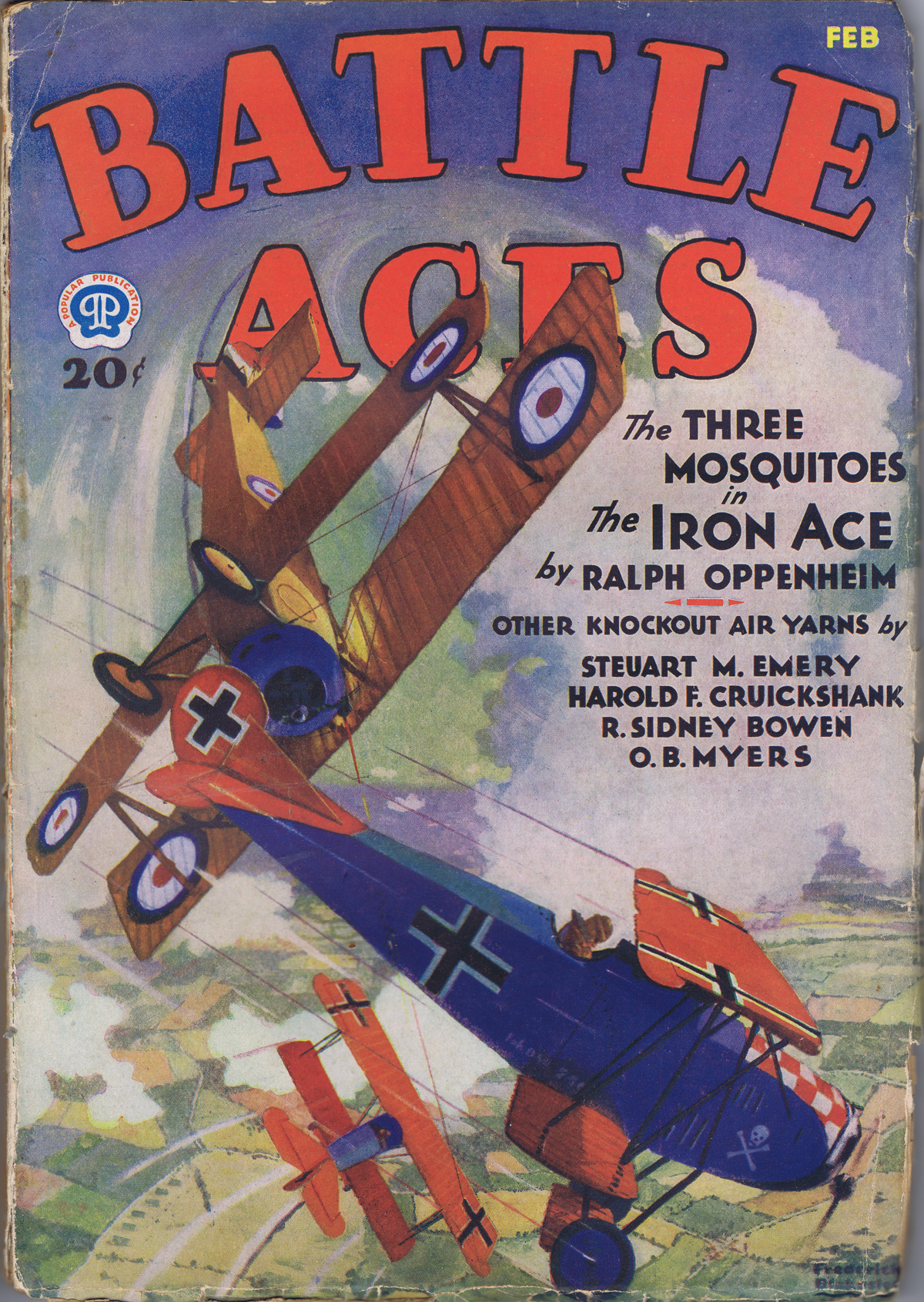

“The Fokker D-7″ by Frederick Blakeslee

Editor’s Note: This month’s cover is the ninth of the actual war-combat pictures which Mr. Blakeslee, well-known artist and authority on aircraft, is painting exclusively for BATTLE ACES. The series was started to give our readers authentic pictures of war planes in color. It also enables you to follow famous airmen on many of their amazing adventures and fell the same thrills of battle they felt. Be sure to save these covers if you want your collection of this fine series to be complete.

THE HERO of the exploit featured this month is Lieutenant-colonel William Avery Bishop, the ace of aces. In his many combats, numbering over two hundred, he made an official score of seventy-two enemy planes, destroyed. Seventy-five percent of these combats were undertaken alone and the majority were against great odds. In a single day, his last in France, he brought up his score from sixty-seven to seventy-two, by destroying, unaided, five enemy ships in less than two hours.

THE HERO of the exploit featured this month is Lieutenant-colonel William Avery Bishop, the ace of aces. In his many combats, numbering over two hundred, he made an official score of seventy-two enemy planes, destroyed. Seventy-five percent of these combats were undertaken alone and the majority were against great odds. In a single day, his last in France, he brought up his score from sixty-seven to seventy-two, by destroying, unaided, five enemy ships in less than two hours.

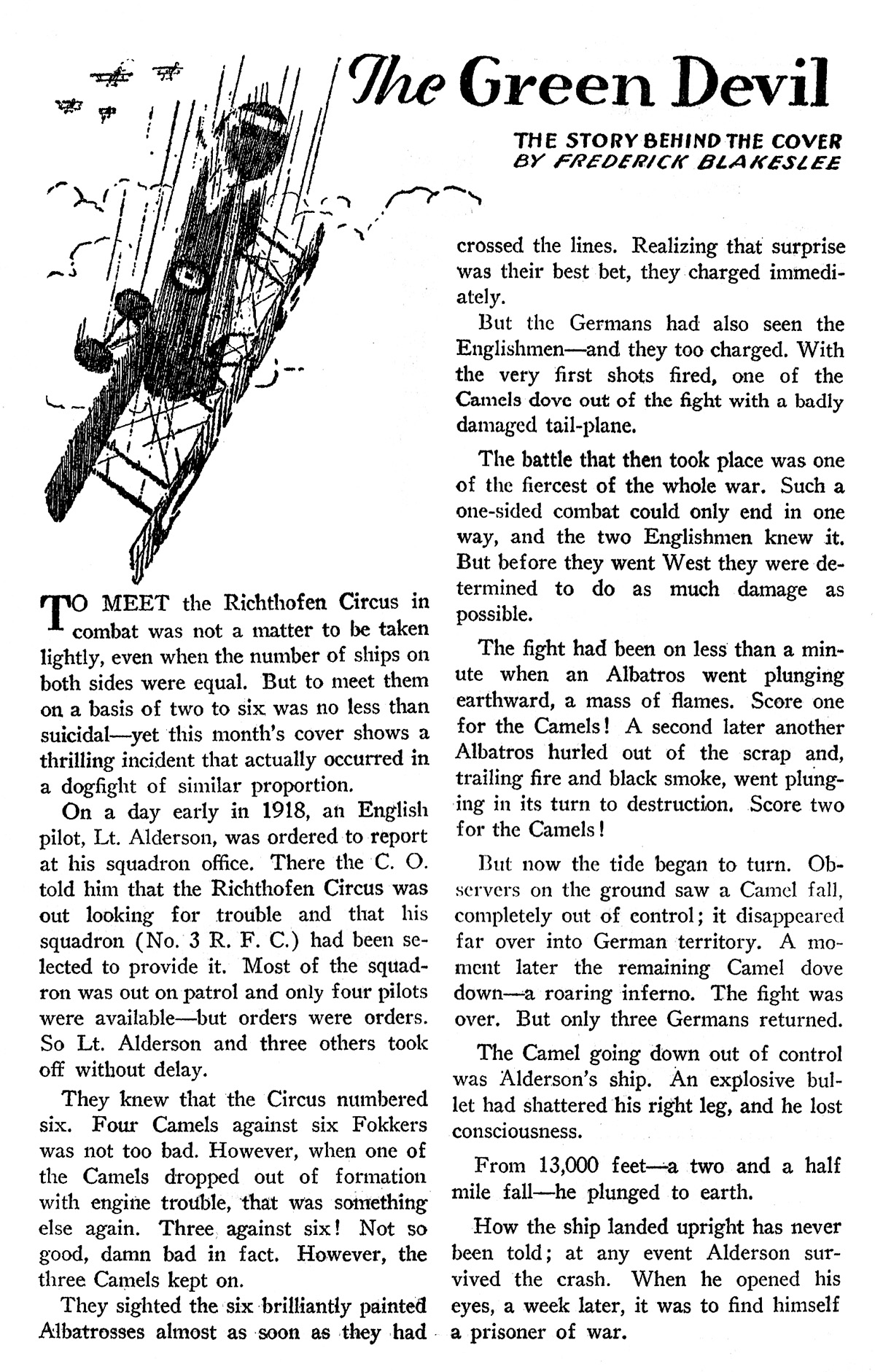

Here is the story of the action which is illustrated on the cover. It will give an insight into the daring of this fighter. The combat took place on August 11, 1917. Colonel Bishop went out that day to work independently, as was his custom. Finding the air clear of patrols, he flew to an enemy airdrome only to find it deserted. He then flew on, going at least twelve miles beyond the lines into German territory, until he discovered another airdrome. Here there was great activity. Seven planes, some with their engines running, were lined up in front of the hangars, preparing to ascend. This was just what he had hoped to find.

With throttle wide open, Bishop dove to within fifty feet of the ground, sending a stream of lead into the group of men and planes. He noticed one casualty as the pilots and mechanics scattered in all directions. The Boches manned the ground guns and raked the sky, while the pilots worked frantically to take off. They knew whom they were up against. There was no mistaking “Blue Nose,” which was the name of Bishop’s machine. Furthermore, who but Bishop would come so far into their territory, and have the audacity to attack an airdrome all by himself?

Here, right in their midst, was the man most feared and most “wanted” by the Germans. It meant promotion and an Iron Cross for the pilot who downed him. However he was not easily downed.

At last one Jerry left the ground. Bishop was on his tail like a hawk and before the Jerry could gain maneuvering altitude, Bishop gave him fifteen rounds of hot fire, crashing him to the ground. During this brief action another plane took off but Bishop was too quick for him. He swung around and in a flash was on his tail. Thirty rounds sent this Boche crashing into a tree. In the meantime two more enemy ships had taken off and had gained enough altitude for a serious scrap. These Bishop engaged at once. He attacked the first ship, his guns ripping out one of those short bursts at close range, which were his specialty. The enemy ship went spinning to earth, crashing three hundred yards from the airdrome. He then emptied a full drum into the second hostile machine, doing more moral than material damage, for this plane took to its heels.

Then Captain Bishop flew back to his airdrome, pursued for over a mile by four enemy scouts, who were too discouraged to do any harm. When Bishop left the Front he had won the M.C., the D.F.C., the D.S.O. and bar, the Legion of Honor, the Croix de Guerre, and Briton’s highest award, the V.C. For the action here illustrated he was awarded the D.S.O.

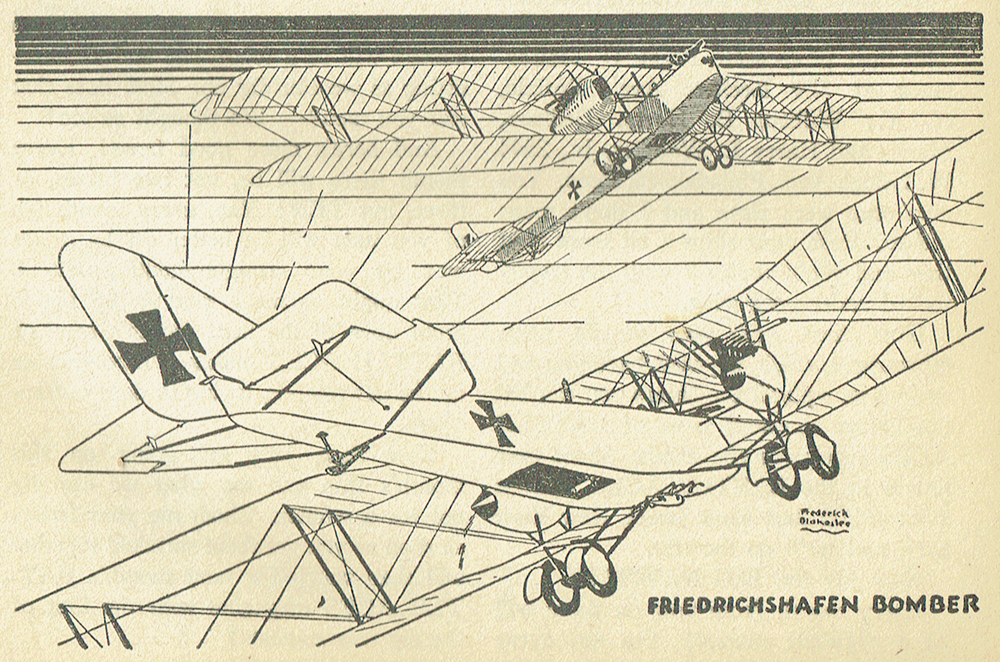

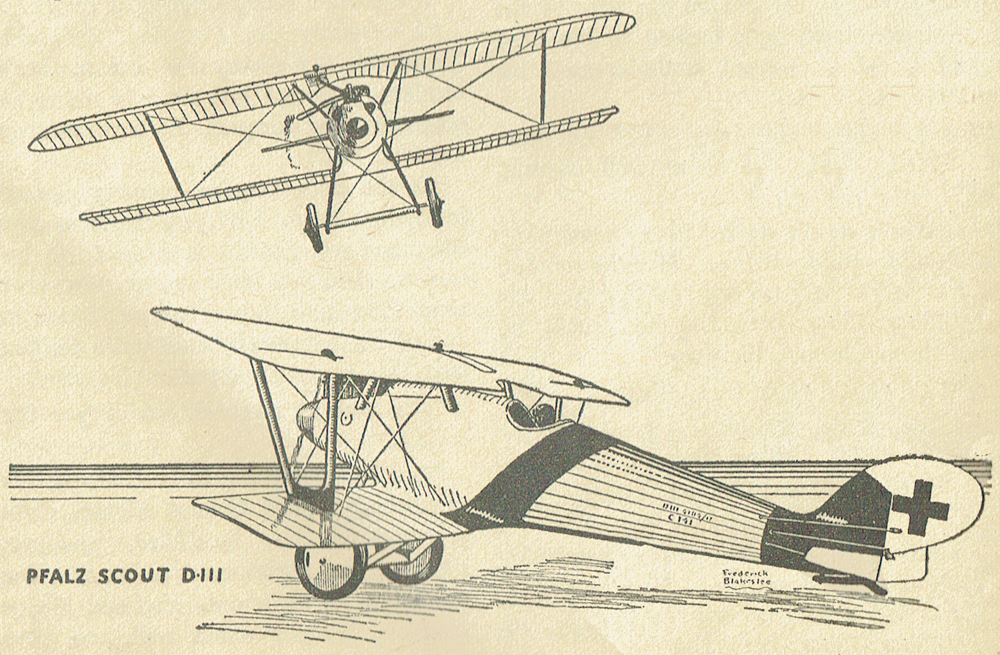

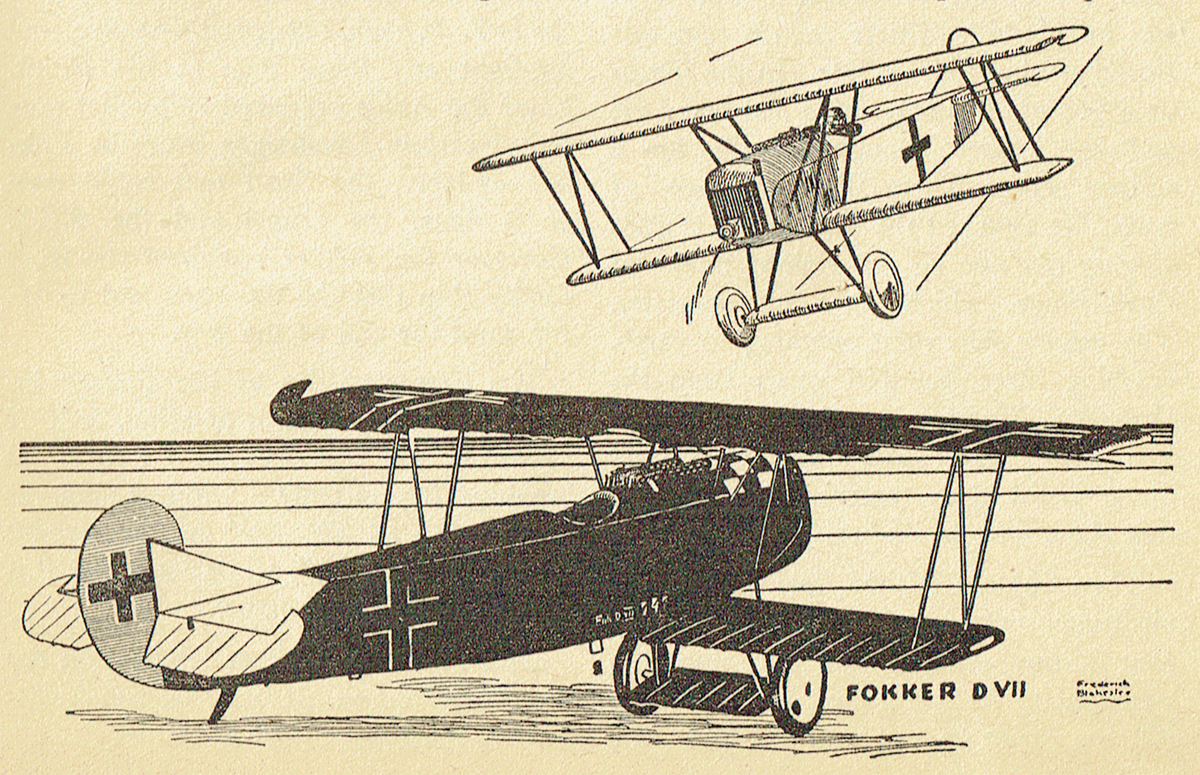

You will recognize the enemy machine as a Fokker D-7, “The Wolf of the Air.” In the hands of a good pilot it was a terror to the Allied forces. It was designed by Anthony Fokker who was not a German, but a subject of Holland. He is now a citizen of the United States.

This remarkable ship might have been on the Allied side, if it had not been for the short-sightedness of official England; for Fokker offered his services to England and was rejected. He then went to Germany where his value was recognized and where he was immediately employed. England, realizing her mistake, offered Fokker two million pounds to leave Germany. Since Fokker was virtually a prisoner there—but that is another story.

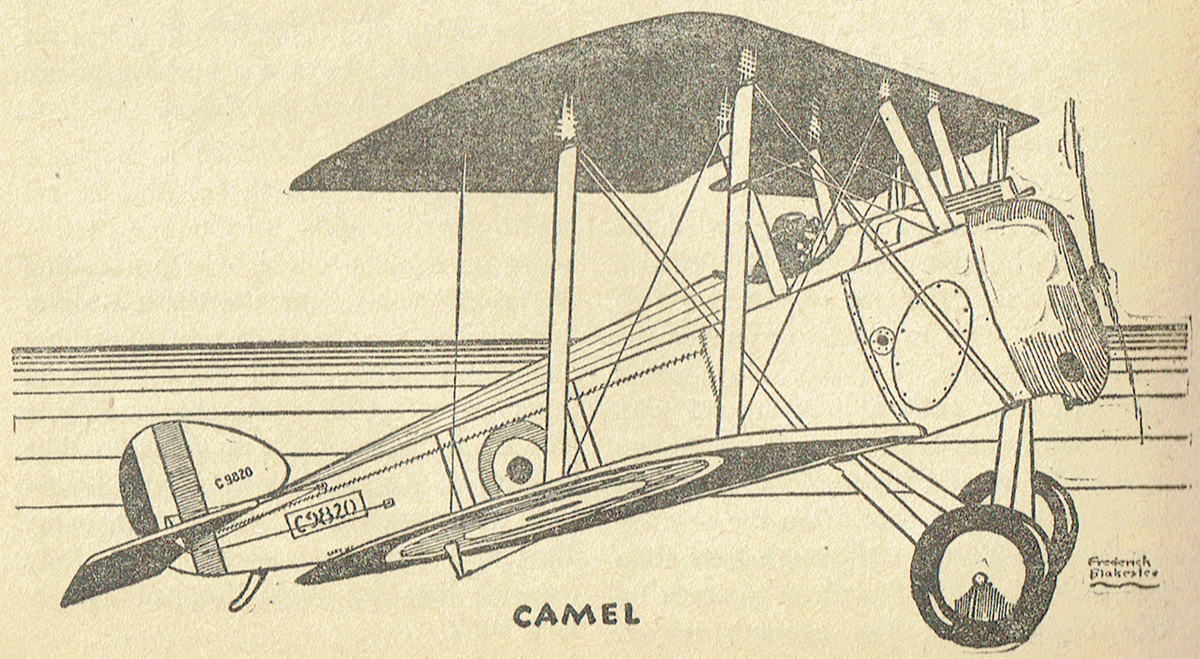

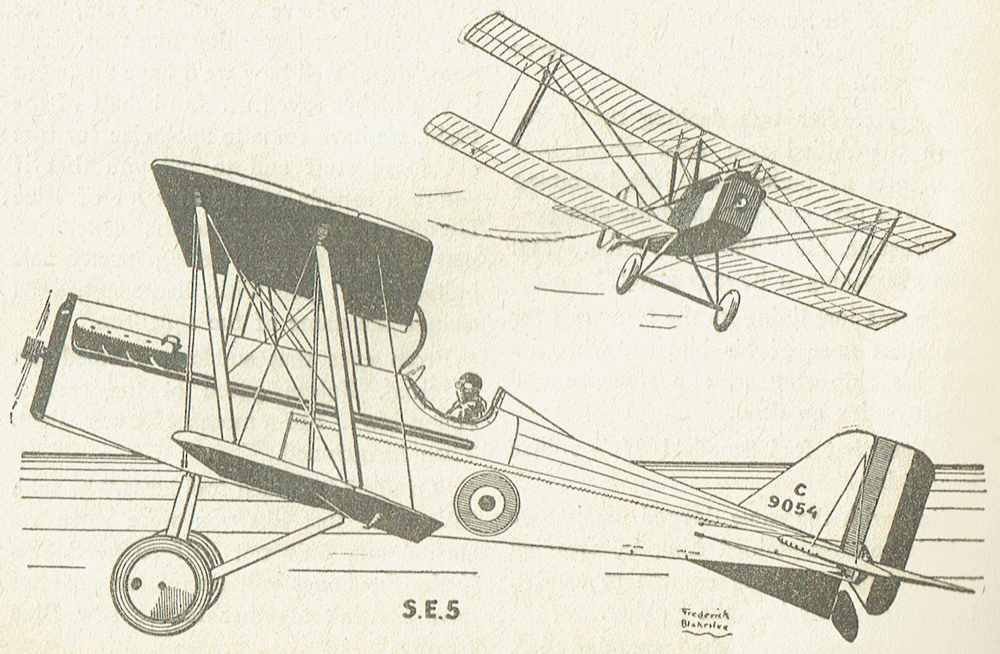

At any rate Fokker built the Germans a ship which filled the Allied pilots with wonder and consternation when it first appeared over the lines. This ship was the D-7. It could out-speed, out-dive, and out-fight any thing then at the Front. Later the Allies produced ships that possessed certain advantages over the Fokker—notably, the Spad that could turn on a dime, the Camel and the S.E.5. However the Fokker remained the most deadly ship that the Germans had to offer, until the end of the war.

The characteristics of the Fokker include an extreme depth of wing, lack of dihedral, and the absence of external bracing. It was truly a wireless ship. It had a span of 29′ 3½” and an overall length of 22′ 11½”, while its speed was about 116 miles per hour.

“The Fokker D-7″ by Frederick M. Blakeslee (February 1932)

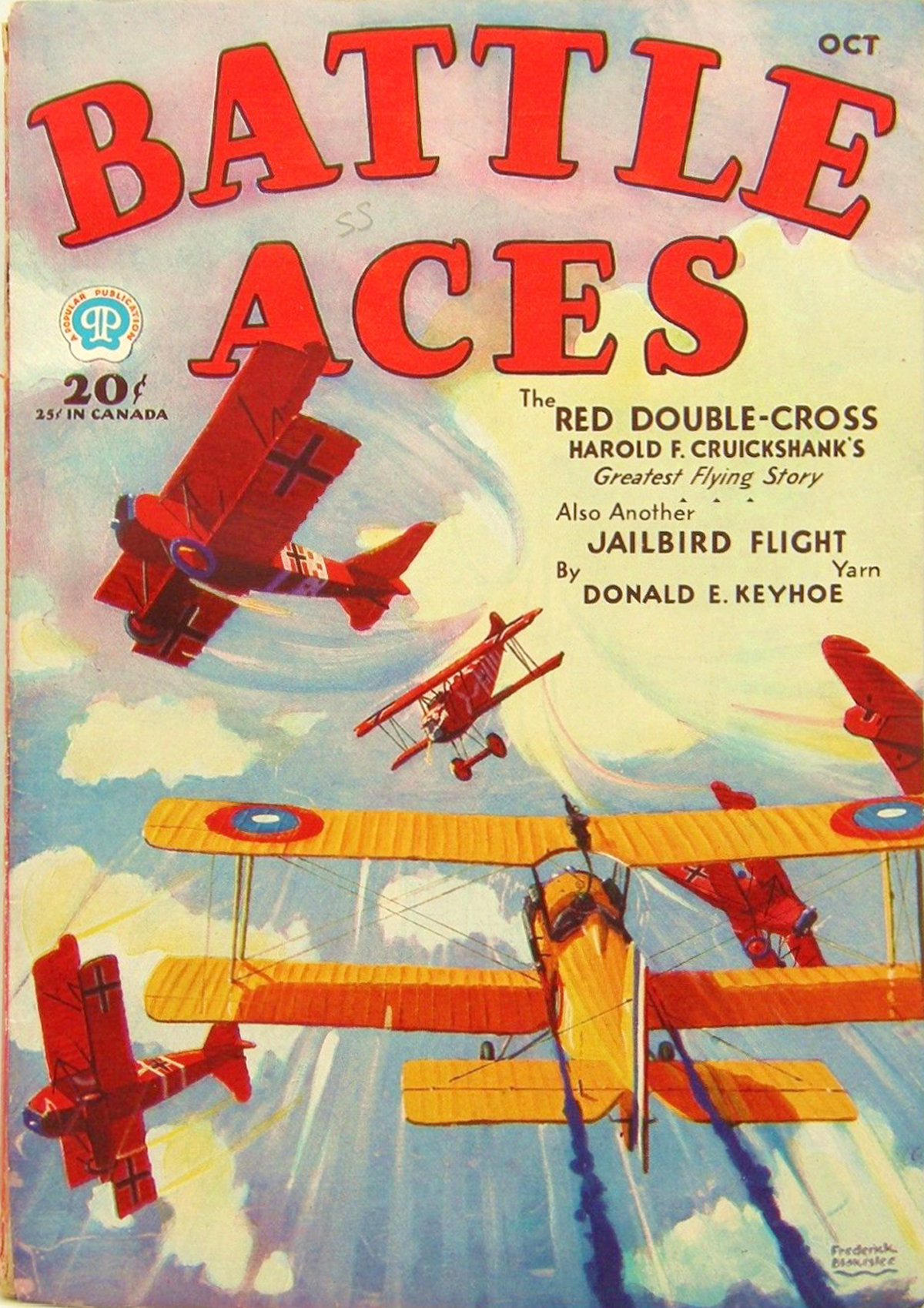

You will see a Fokker triplane on the cover next month. It is Baron von Richthofen’s machine, so don’t miss it!