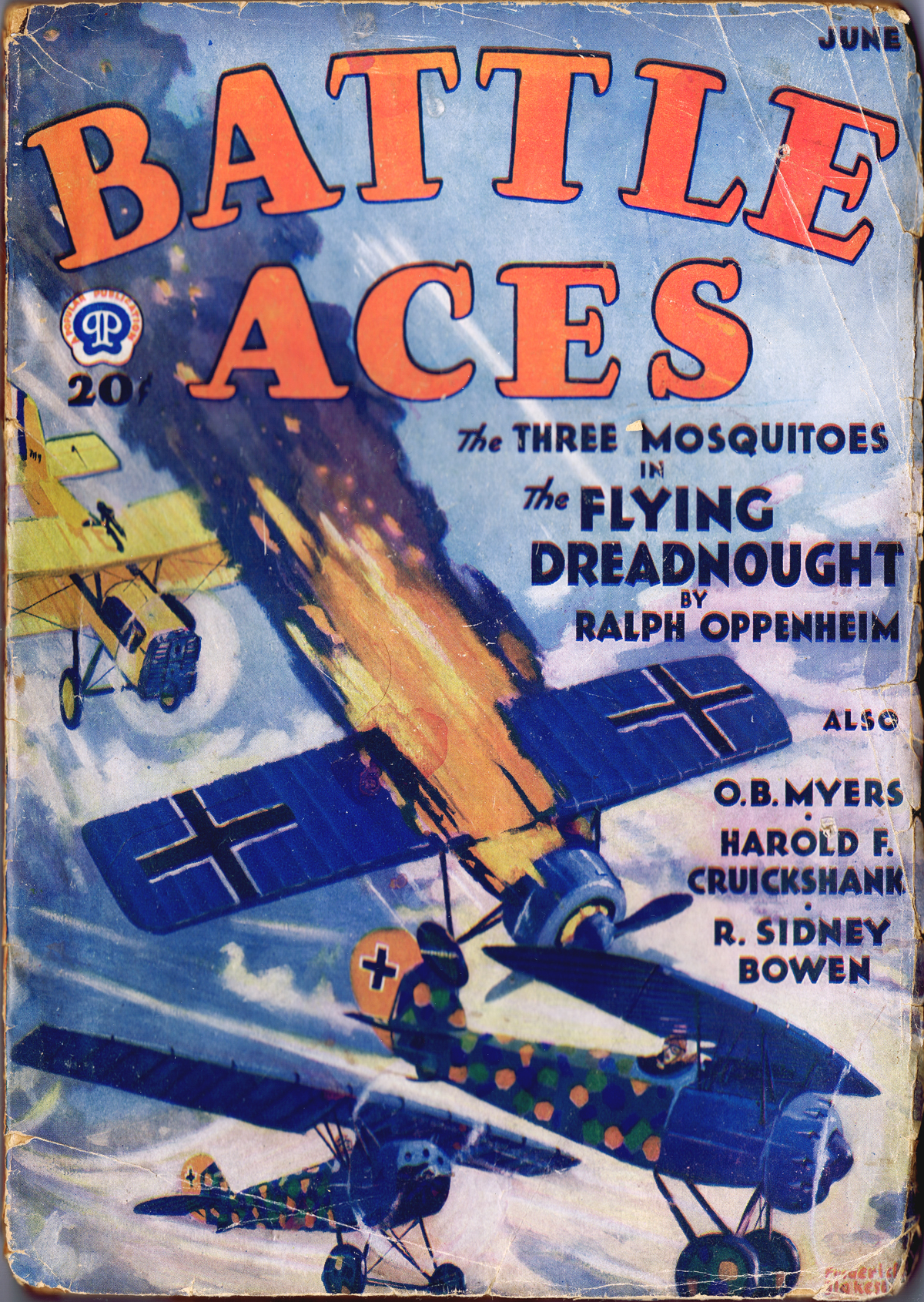

“The Bourges Bomber” by Frederick Blakeslee

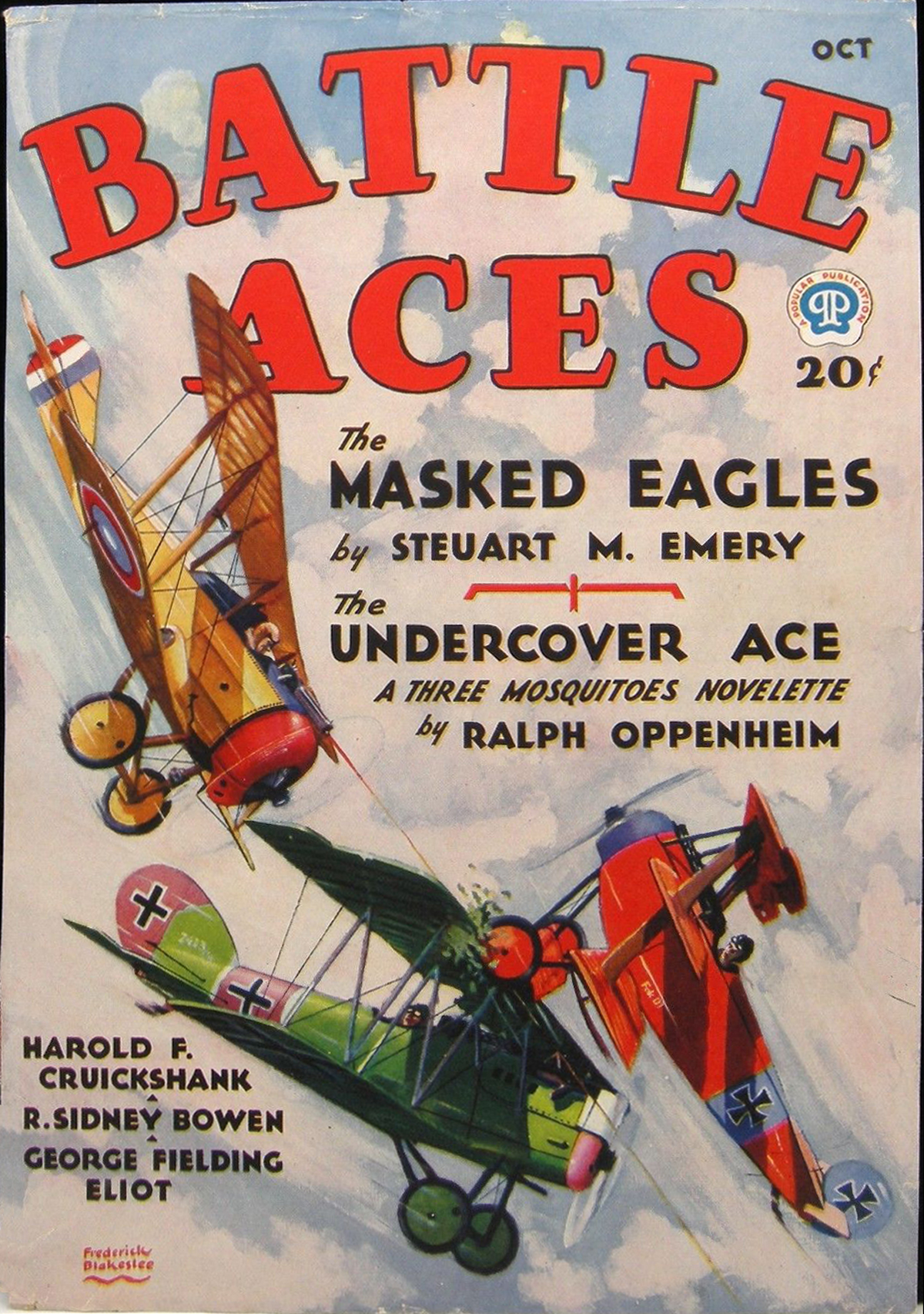

Frederick Blakeslee painted all the covers for the entire run of Dare-Devil Aces. And each of those covers had a story behind it. This time, Blakeslee presents us with more of the approach he used for the covers he painted for Battle Aces—telling us about the ship on cover of the September 1934 cover for Dare-Devil Aces. . . .

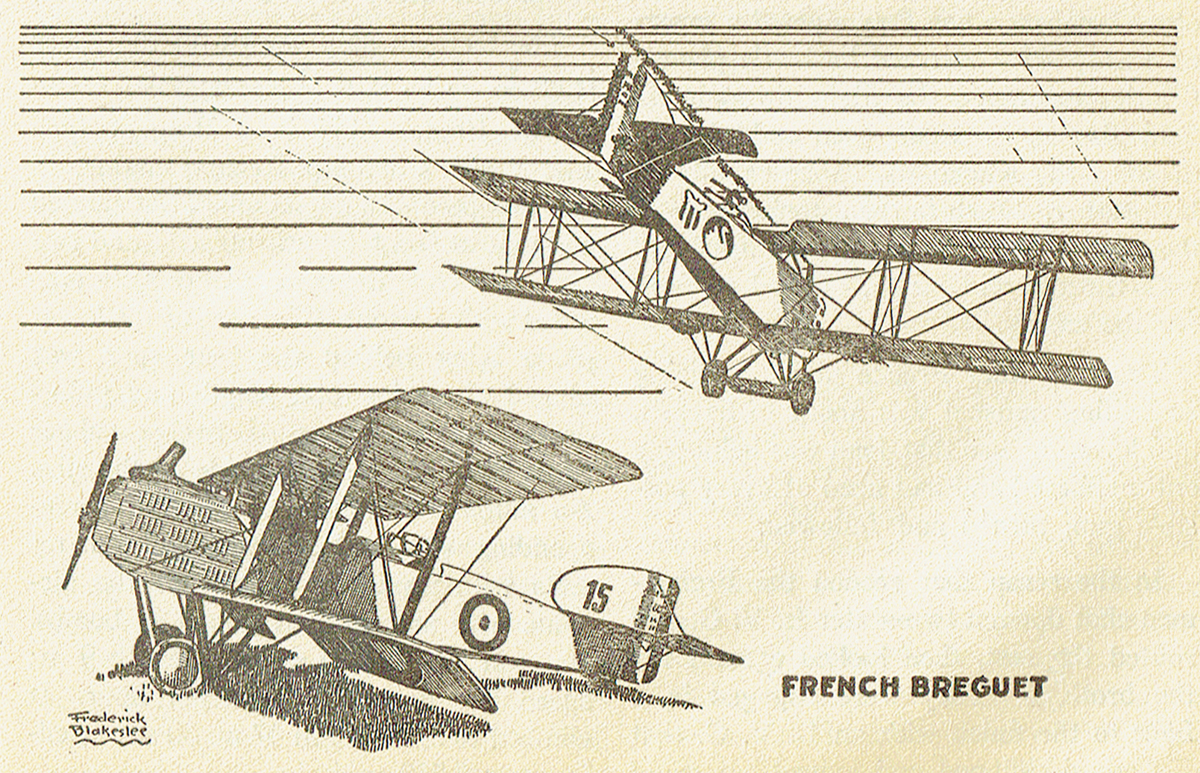

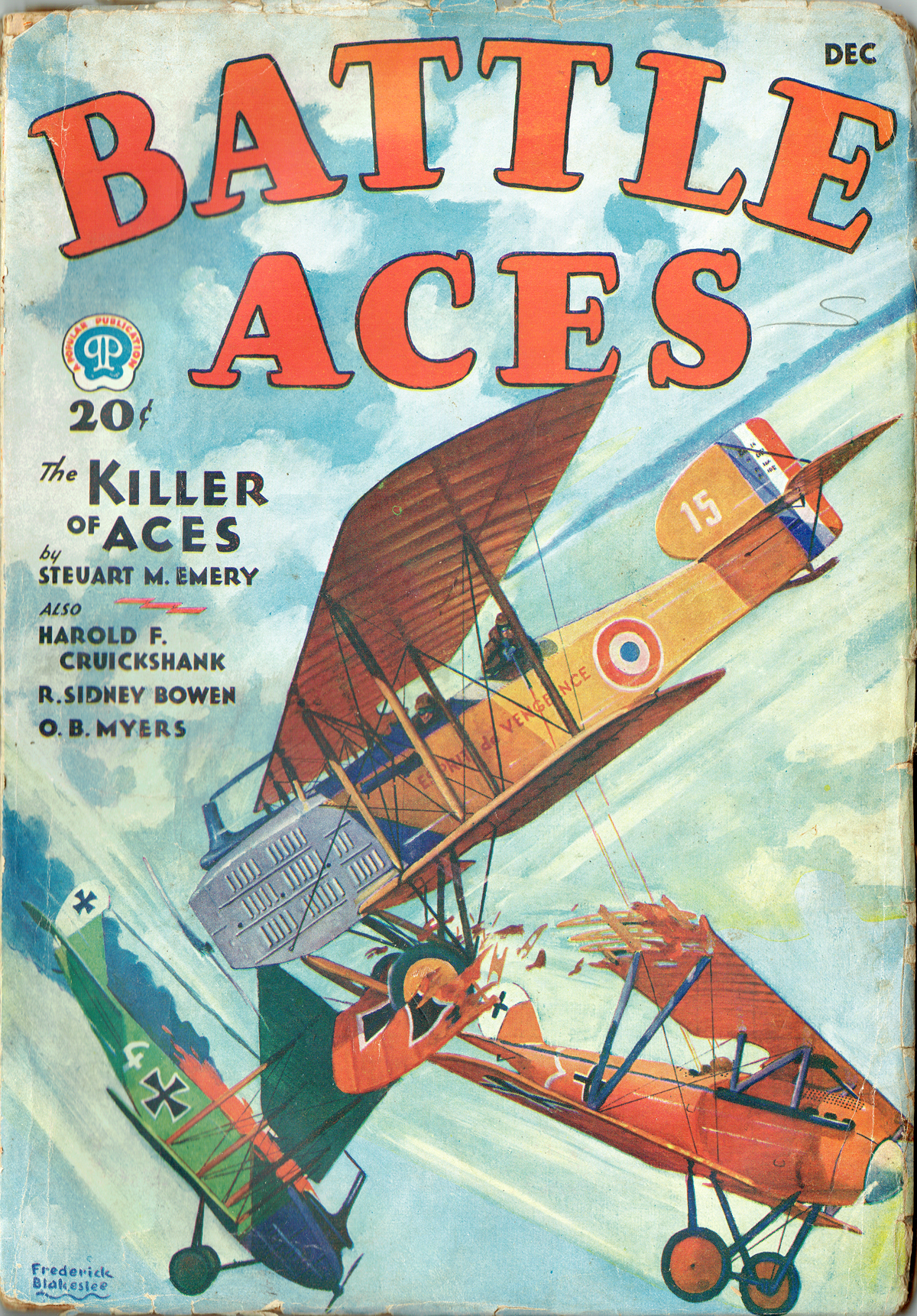

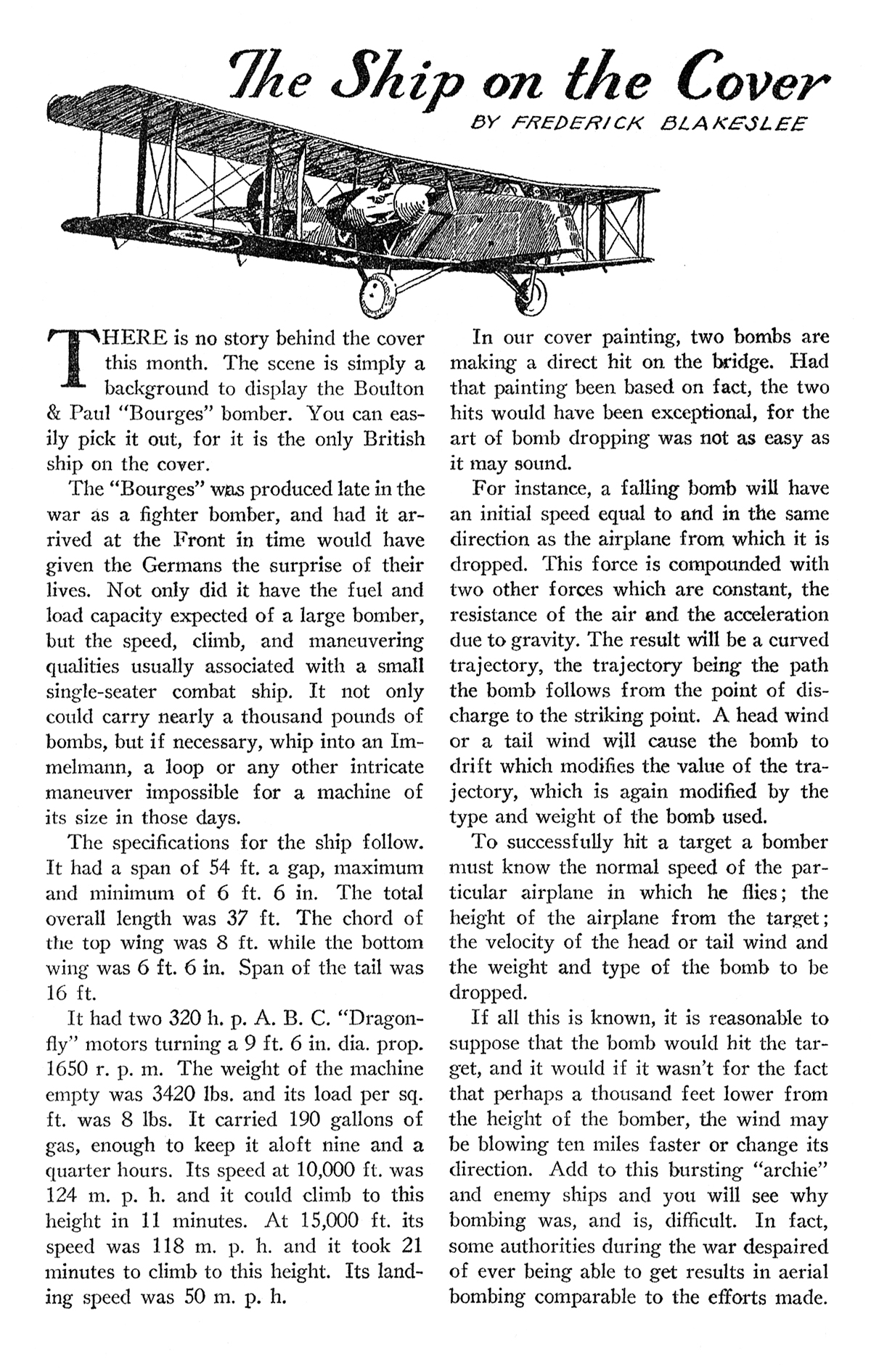

THERE is no story behind the cover this month. The scene is simply a background to display the Boulton & Paul “Bourges” bomber. You can easily pick it out, for it is the only British ship on the cover.

THERE is no story behind the cover this month. The scene is simply a background to display the Boulton & Paul “Bourges” bomber. You can easily pick it out, for it is the only British ship on the cover.

The “Bourges” was produced late in the war as a fighter bomber, and had it arrived at the Front in time would have given the Germans the surprise of their lives. Not only did it have the fuel and load capacity expected of a large bomber, but the speed, climb, and maneuvering qualities usually associated with a small single-seater combat ship. It not only could carry nearly a thousand pounds of bombs, but if necessary, whip into an Immelmann, a loop or any other intricate maneuver impossible for a machine of its size in those days.

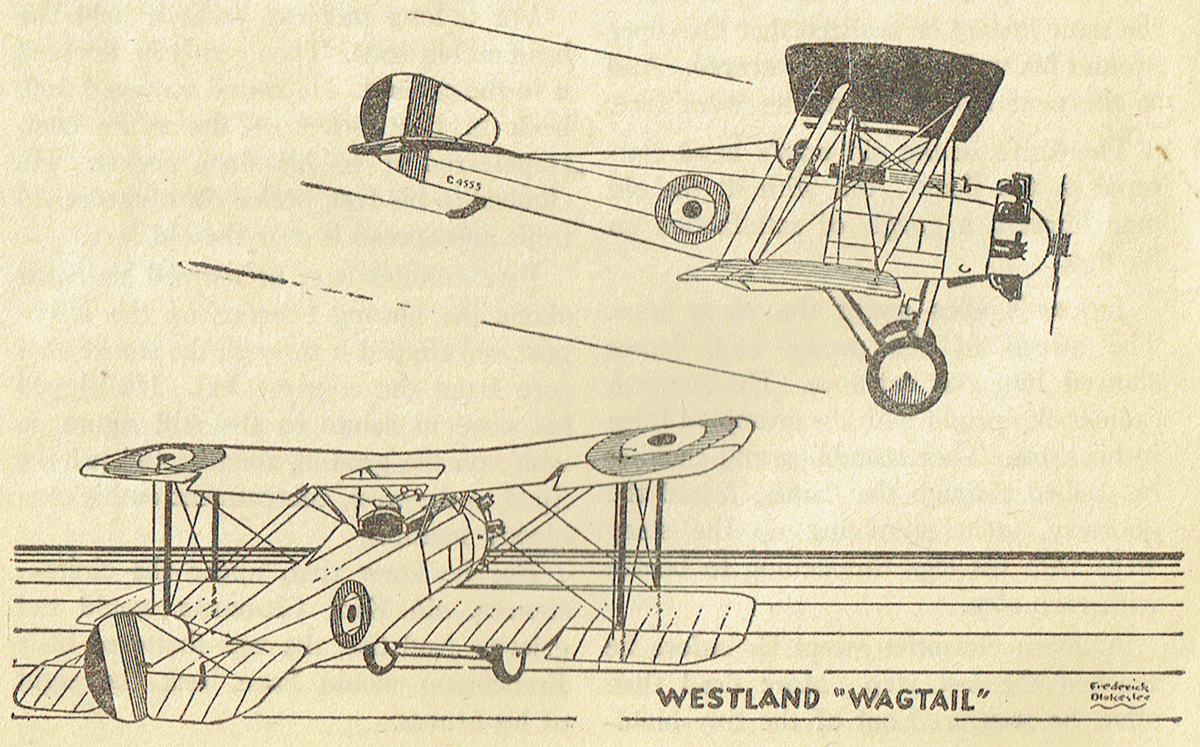

The specifications for the ship follow. It had a span of 54 ft. a gap, maximum and minimum of 6 ft. 6 in. The total overall length was 37 ft. The chord of the top wing was 8 ft. while the bottom wing was 6 ft. 6 in. Span of the tail was 16 ft.

It had two 320 h.p. A. B. C. “Dragonfly” motors turning a 9 ft. 6 in. dia. prop. 1650 r.p.m. The weight of the machine empty was 3420 lbs. and its load per sq. ft. was 8 lbs. It carried 190 gallons of gas, enough to keep it aloft nine and a quarter hours. Its speed at 10,000 ft. was 124 m.p.h. and it could climb to this height in 11 minutes. At 15,000 ft. its speed was 118 m.p.h. and it took 21 minutes to climb to this height. Its landing speed was 50 m.p.h.

In our cover painting, two bombs are making a direct hit on the bridge. Had that painting been based on fact, the two hits would have been exceptional, for the art of bomb dropping was not as easy as it may sound.

For instance, a falling bomb will have an initial speed equal to and in the same direction as the airplane from which it is dropped. This force is compounded with two other forces which are constant, the resistance of the air and the acceleration due to gravity. The result will be a curved trajectory, the trajectory being the path the bomb follows from the point of discharge to the striking point. A head wind or a tail wind will cause the bomb to drift which modifies the value of the trajectory, which is again modified by the type and weight of the bomb used.

To successfully hit a target a bomber must know the normal speed of the particular airplane in which he flies; the height of the airplane from the target; the velocity of the head or tail wind and the weight and type of the bomb to be dropped.

If all this is known, it is reasonable to suppose that the bomb would hit the target, and it would if it wasn’t for the fact that perhaps a thousand feet lower from the height of the bomber, the wind may be blowing ten miles faster or change its direction. Add to this bursting “archie” and enemy ships and you will see why bombing was, and is, difficult. In fact, some authorities during the war despaired of ever being able to get results in aerial bombing comparable to the efforts made.

“The Bourges Bomber: The Ship on the Cover” by Frederick Blakeslee

(September 1934, Dare-Devil Aces)

Next time, Eliot Todd returns with the story of “T.N.T. Wings” on the October 1934 cover. Be sure not to miss it.