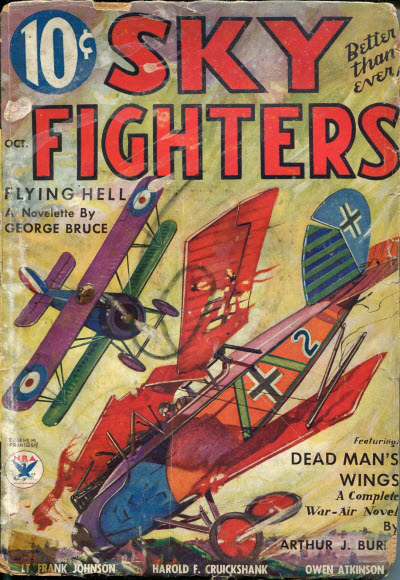

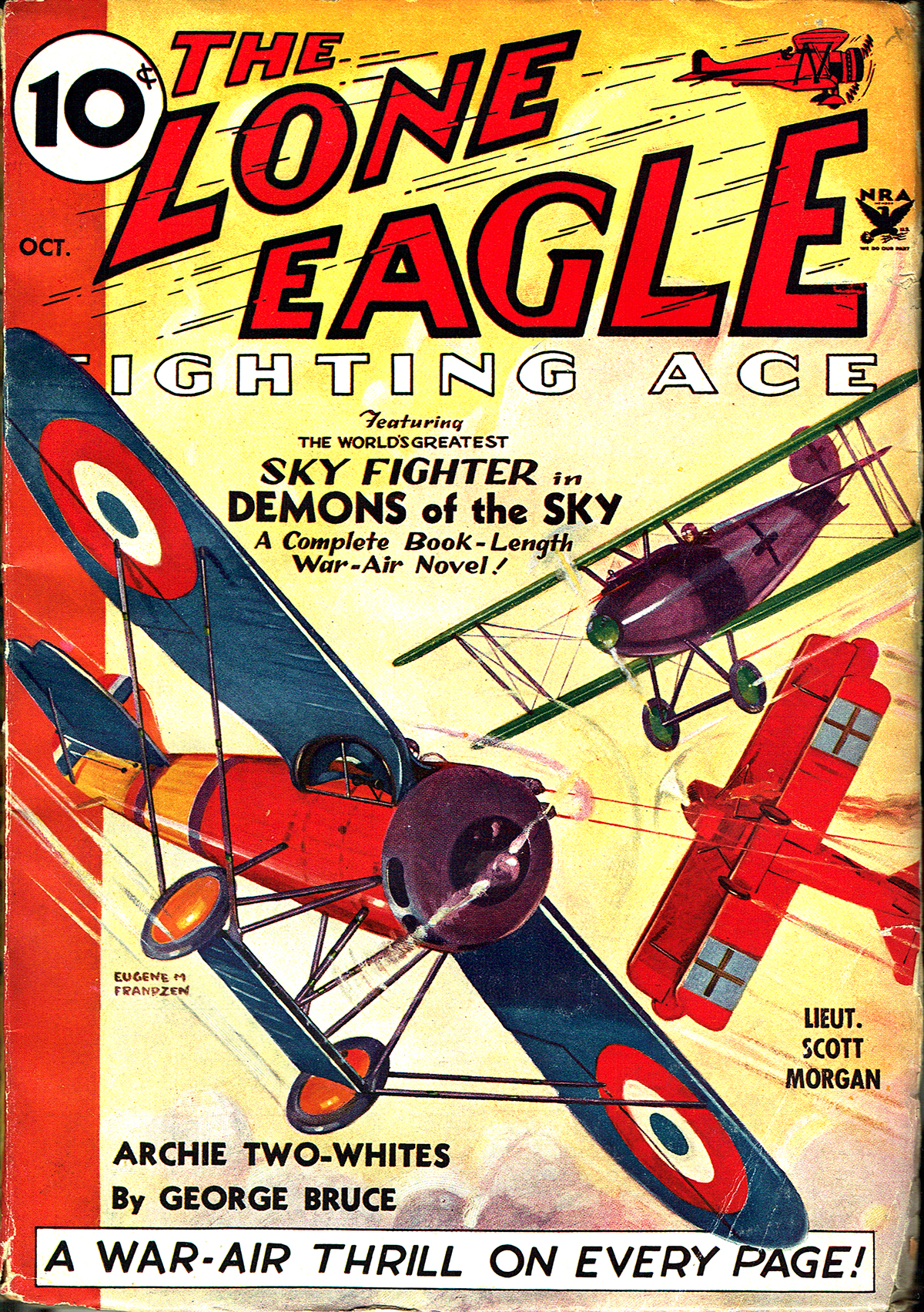

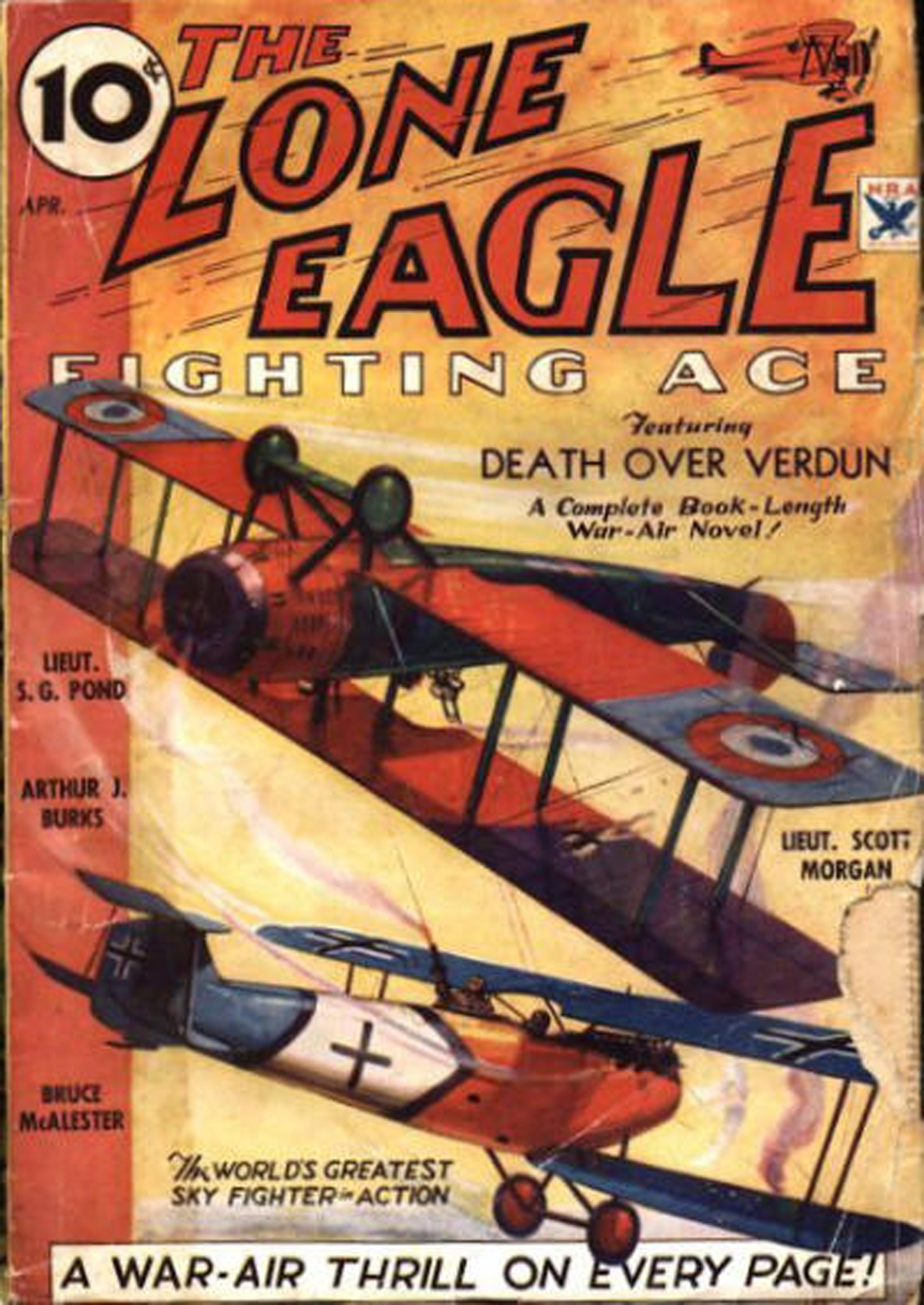

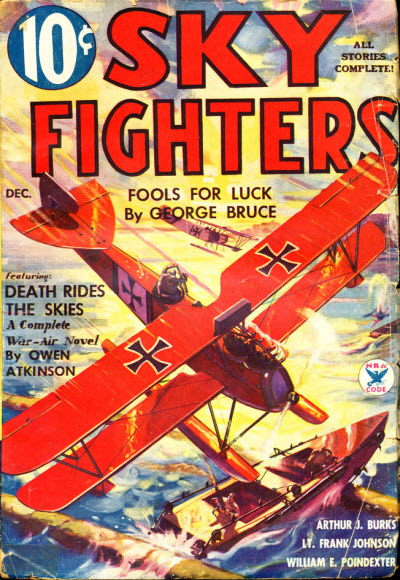

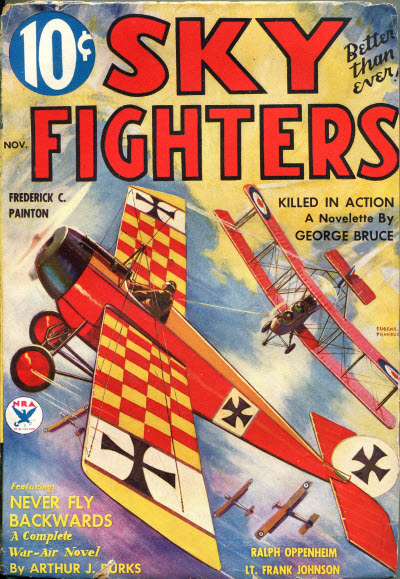

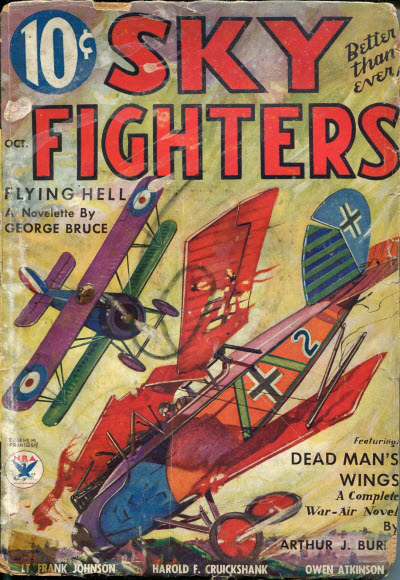

FROM the pages of the October 1934 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

What Made ‘Em Fly

by Lt. Edward McCrae (Sky Fighters, October 1934)

NOW you wise young sons and daughters of a double eagle, or maybe it was a buzzard, maybe you hadn’t noticed it before but if you had looked a little carefully at all the nice pictures of the war crates on the covers of SKY FIGHTERS you might have noticed that nearly every one of them without exception had something peculiar about it. Whether you noticed it or not, they all had engines in ’em.

Yes, sir, they carried whole gasoline engines up in the air. Some of them had one and some had two and some had more than that—even back in the early days of the war.

Now if I know anything about you clucks you’re just as likely as not to come asking me why those aviators wanted to load themselves down with a lot of machinery. It would be just about like you.

So I’m going to head you off and tell you something about those powerhouses we used to take upstairs along with us. And don’t be asking me why they carried more than one of ’em. I’m going to get to that if you’ll let me. Mary, don’t you throw that spit-ball!

You Gotta Have an Engine

Maybe your papas have let you look under the hood of the old family car, in which case you might have learned the secret that a vehicle just can’t get along without an engine if it’s going to do any good running at all. Honey, it’s the same way with an airplane.

So I’m going to tell you a few simple things that won’t be too difficult for your shallow pans to remember so you will have a little inkling of why they have all different kinds of engines when it would look for the world like if they got a good one they would keep using it instead of trying to think up other designs and shapes to use.

You might have noticed that some of the engines when they were looked at from the front looked like stars with a lot of cylinders all sticking out every which way from the center. And others looked more like a common every-day automobile engine. How come it and why?

Air and Water Cooling

The answer is, my precious little dunderheads, that some of them were air-cooled and some water-cooled.

They learned that an engine that didn’t have to tote its own drink along with it weighed about three-quarters as much as another of the same horsepower that was water-cooled. And they learned also that for every pound you could reduce the weight of it you could add two pounds of useful load, or what amounts to the same thing, you could have a bigger engine and more power for the given weight.

Now the reason you could get those two extra pounds where one grew before was that when you took a pound’s weight away from the engine you could reduce the weight of the ship by another pound that was necessary to strengthen it to support the pound you took away, and you could further reduce the weight of your ship by another pound that went to strengthen the wing so it would support that extra pound of engine weight. That’s as clear as mud, isn’t it?

But unfortunately that added strength didn’t always show as engines got bigger. After they got so big, an air-cooled engine wouldn’t weigh any less than a water-cooled one for the same horse power.

So they used one or the other depending on the performance they wanted.

The Air-Foil

Now when you start trying to recognize the different kinds of engines you want to look at the front of them. That way you can see what kind of a surface, or air-foil they present to the wind. That’s the important thing for you to consider.

When you look at them that from that aspect you will see that there are only about three different general groups of designs. Of course, these differ among themselves in slight ways, but after all, even human beings in one family have slight differences.

Take a look at the figure which I have very cleverly called Figure 1. In that you will see the front view of a few of the stationary cylinder engines that are water-cooled and whose fathers got the idea of their design from our old friend the automobile engine. Now this group shows some outline forms of the engines themselves, but there is a fly in the amber. They don’t show the radiators, and a water-cooled engine has to have a radiator and that presents a big flat surface to the air to reduce your speed.

Rotary Engines

So then you have next in what for want of a better name I have called Figure 2, the rotary engines that were used during the war. Some of the names of these are Gnome Rotary, the Le Rhone Rotary, and the Clerget Rotary.

These were funny power plants. You might not believe it when I tell you, but it is a fact that the crank shaft stood still and the whole engine itself revolved around it! That sounds kind of Chinese, doesn’t it? But it isn’t. What with those cylinders whirling around at a thousand revolutions or more, they kept cool pretty well, but once in a while one of them would fly off the handle and scatter cylinders all over No-Man’s-Land.

And then they had another feature that the brass hats didn’t seem to bother about, but which we didn’t like at all. They were lubricated with castor oil!

Hot Castor Oil

Our objections to it came, not because we had to share their fuel oil, but because the engineers didn’t think castor oil was bad enough cold, they let it get hot in the motor.

And brothers and sisters, you have not smelled nothing yet until you have got a nose full of red hot castor oil. And you can smell it for miles—and that is not an exaggeration! We were afraid the Heinies could always tell we were coming by just sticking their noses up in the air and taking a deep breath. Boy, it was awful!

And then you might take a glimpse at a figure that I have designated as Figure 3, even though you can’t count up that high.

Those figures in that picture are some outlines that look almost like those rotary babies. But they aren’t. Their cylinders stick out from a common center just like the rotaries, but there is some sense in the way they act. The cylinders stay still and the crank shaft revolves just like any respectable crankshaft ought to do.

We Had ’Em Long Ago

We had them in the old days, and they had all the way from three to twenty cylinders stuck around the shaft.

Those were the babies that have turned out best since the war. But we had a lot of satisfaction out of them. A couple of these babies we liked in those days were the Salmson and the Cosmos Jupiter.

And just to prove how practical these air-cooled babies were, if you will take a glance around an air field today you will see more air-cooled radial motors than any other kind. Babies of that pattern since the war were the first to cross the North Pole, first to fly the English Channel, first to span the Atlantic, and about the first for everything of any importance.

And now that you know all about the different kinds of engines, I’ll give you that promised dope about why they had different numbers in different kinds of ships.

Why the Extra Engines?

There are two reasons they put more than one engine in a ship. One is to increase and distribute the lift and the other is to increase the factor of safety. These two reasons don’t always both appear in the one ship.

But even you pupils of mine ought to be able to see that if you have two engines and one conks you’ve still got a chance to get back safely over your home trenches, and if you’ve got three engines to do the same work there’s almost no chance at all of your having a forced landing in a mess of Krauts. I know about a Handley-Page bomber that went out and got a direct hit that reduced its whole lower wing to a mass of shreds and tatters and knocked one of its engines clear out of it, but the pilot steered it sixty miles back to his home tarmac! Which is something different from landing on your nose in the middle of a few rosettes of shrapnel.

Helps in the Lift

And then in the matter of lift, you will find the heavy bombers had more than one engine so they could lift a lot of weight. You would first think they would just build one big engine to carry it, but that wouldn’t be so good. Let me try to show you why.

Suppose it took a thousand horsepower to lift the desired bomber and its load. They could build one engine of a thousand horsepower all right, but they wouldn’t get a propeller that could use up and deliver all that power. But if they, say, built two five-hundred horsepower engines, they had two props which could use up all that power and besides they had the additional safety factor of the two motors I just spoke about. You might not remember it well, Tillie, but we had plenty of ships with more than one engine during the war.

The Germans were the first to come out with them, although the French were at work on them even before the war broke out. The first German flew with two engines in 1915.

But the French quickly matched them with the old twin-motored Caudron, and the British followed right off the bat with the twin-motored Dyott, which didn’t last a very long time, however. The Government never did put its official okay on the old Dyott, but it was not a bad heavy crate, and it had a lot of features the German Gotha later incorporated.

Then the Italians in the person of the well-known Mr. Caproni burst out across the field with a three-motored ship. It had two eighty-horsepower tractor motors and one ninety-horsepower pusher. Some ship, eh, Tony!

And toward the end of the fracas the British got real ambitious and brought out a ship with four—count them—motors. It just had engines stuck all over it.

They Went in for Numbers

But once they started going in for numbers, do you think the Germans were going to let anybody get ahead of them? No, my masters, not those boys.

We knocked down one of their big bombers in France, and we thought somebody had attached wings to the machine shop itself.

That crate had five motors sprouting out of it.

That might not be a lot of motors these days, but my children, I’ve been talking all this time about the war that was fought a long, long time ago.

And now, take my blessing, and go out and jump in your ten-motored kiddie cars and zoom out of my sight. Or else I’ll be counting motors instead of sheep in my sleep.

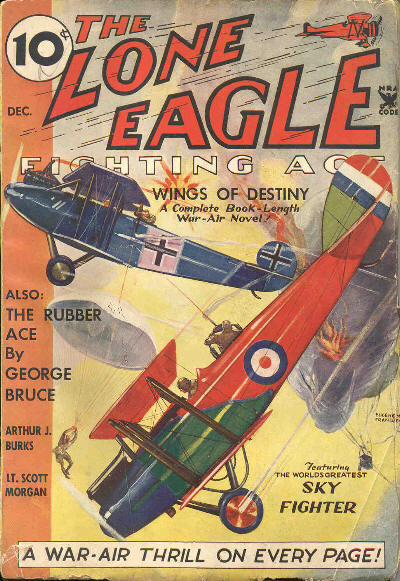

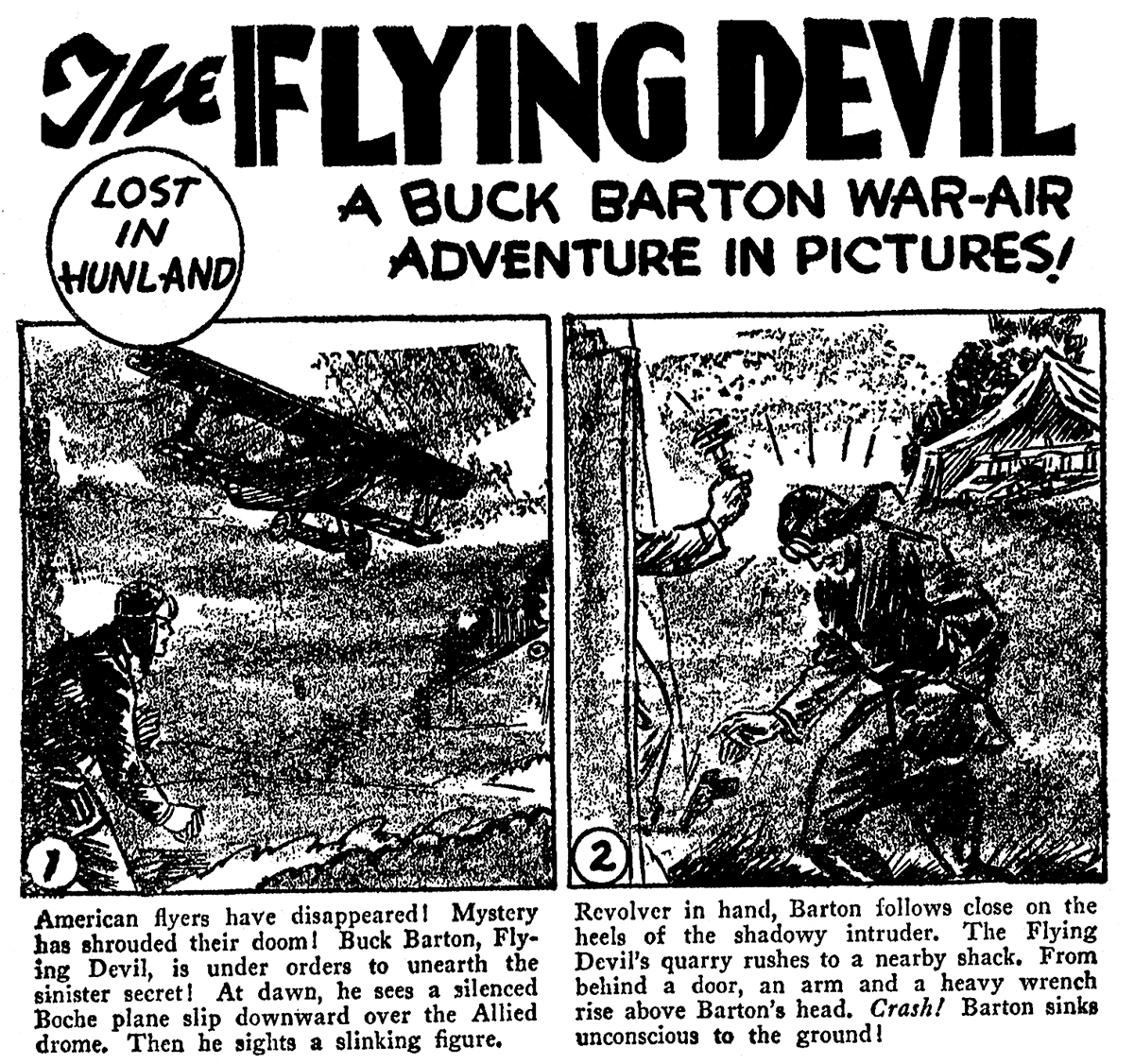

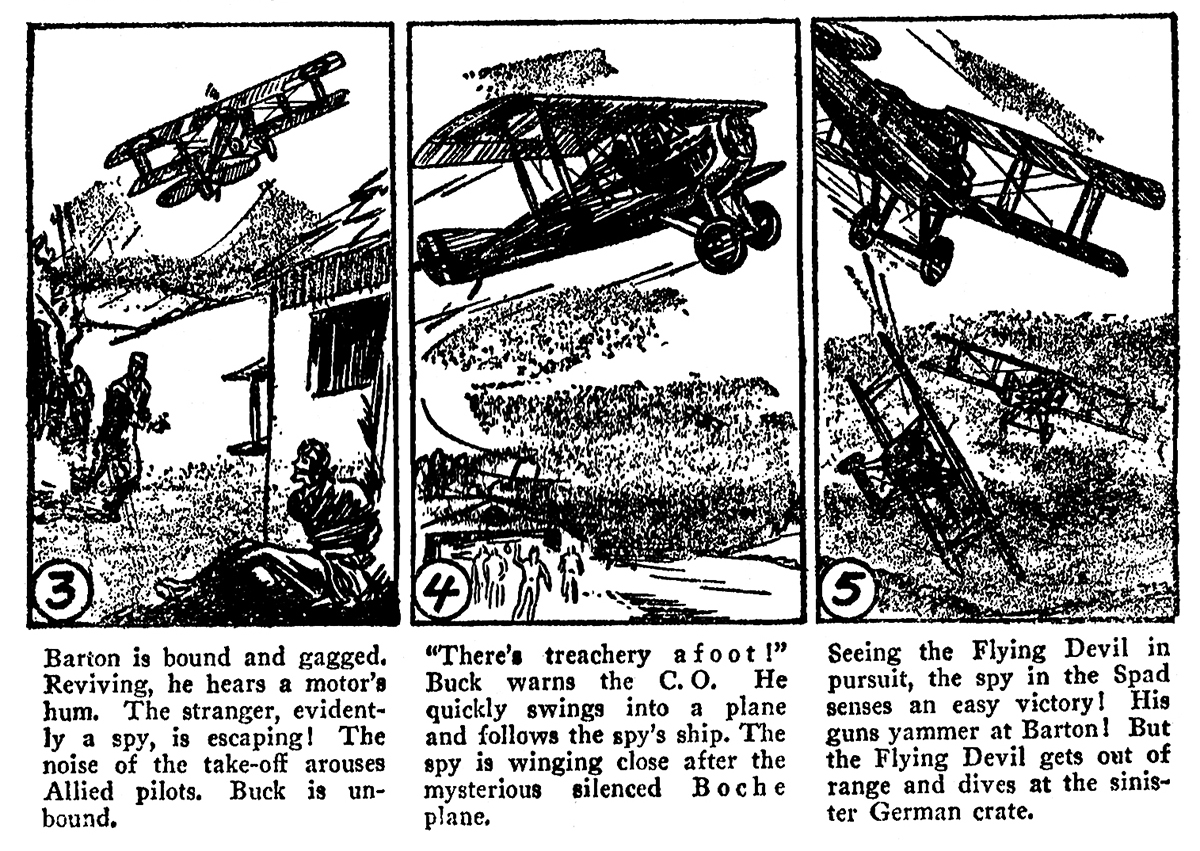

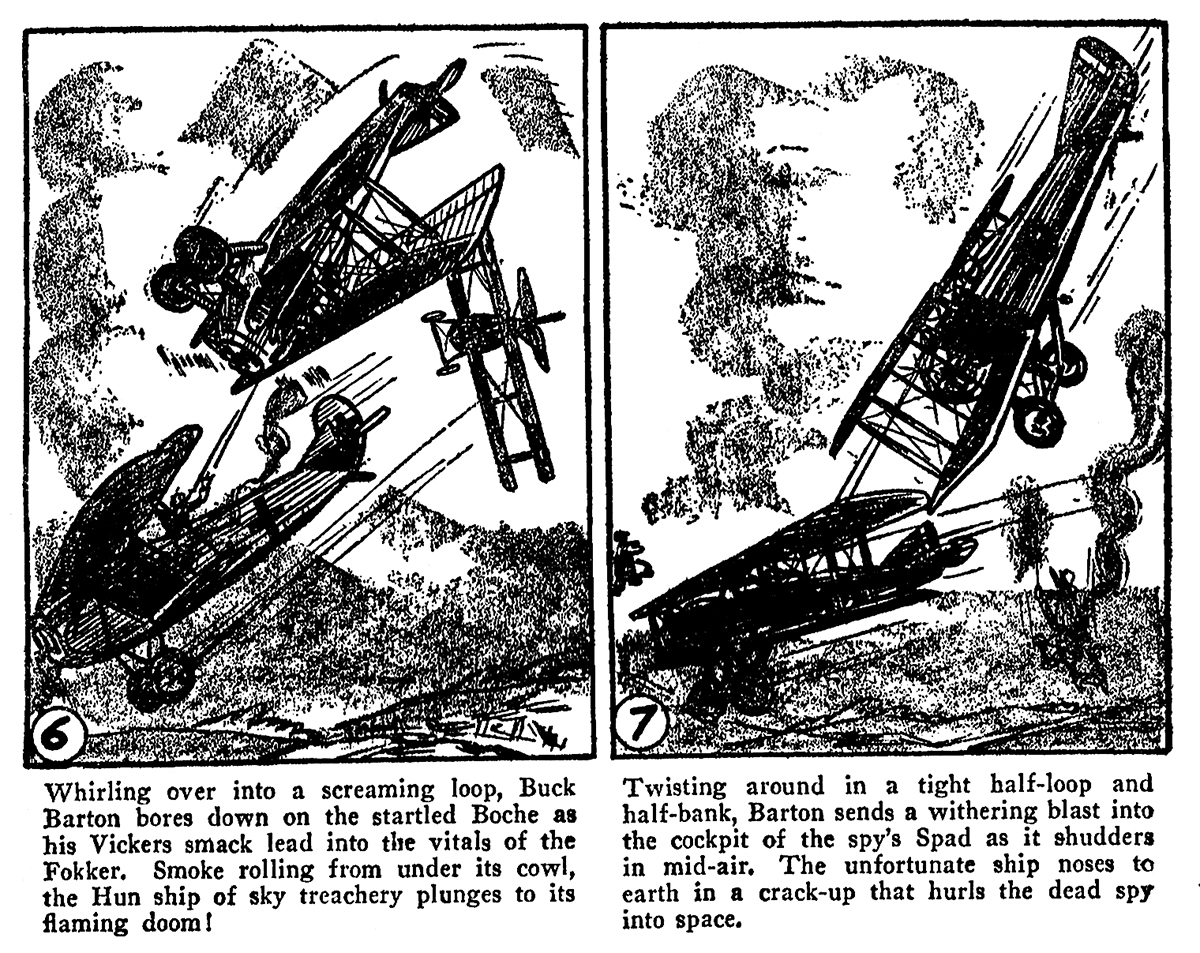

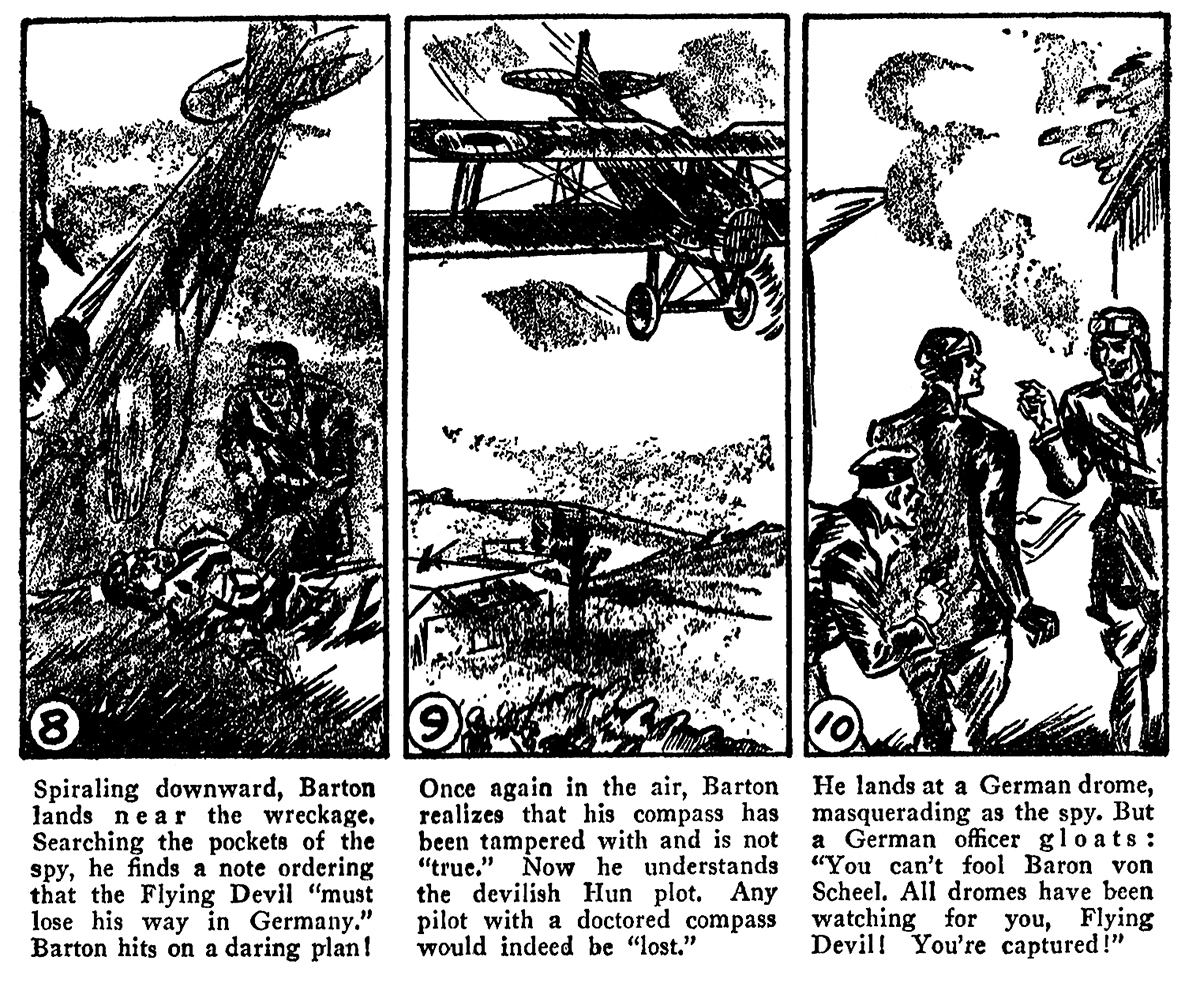

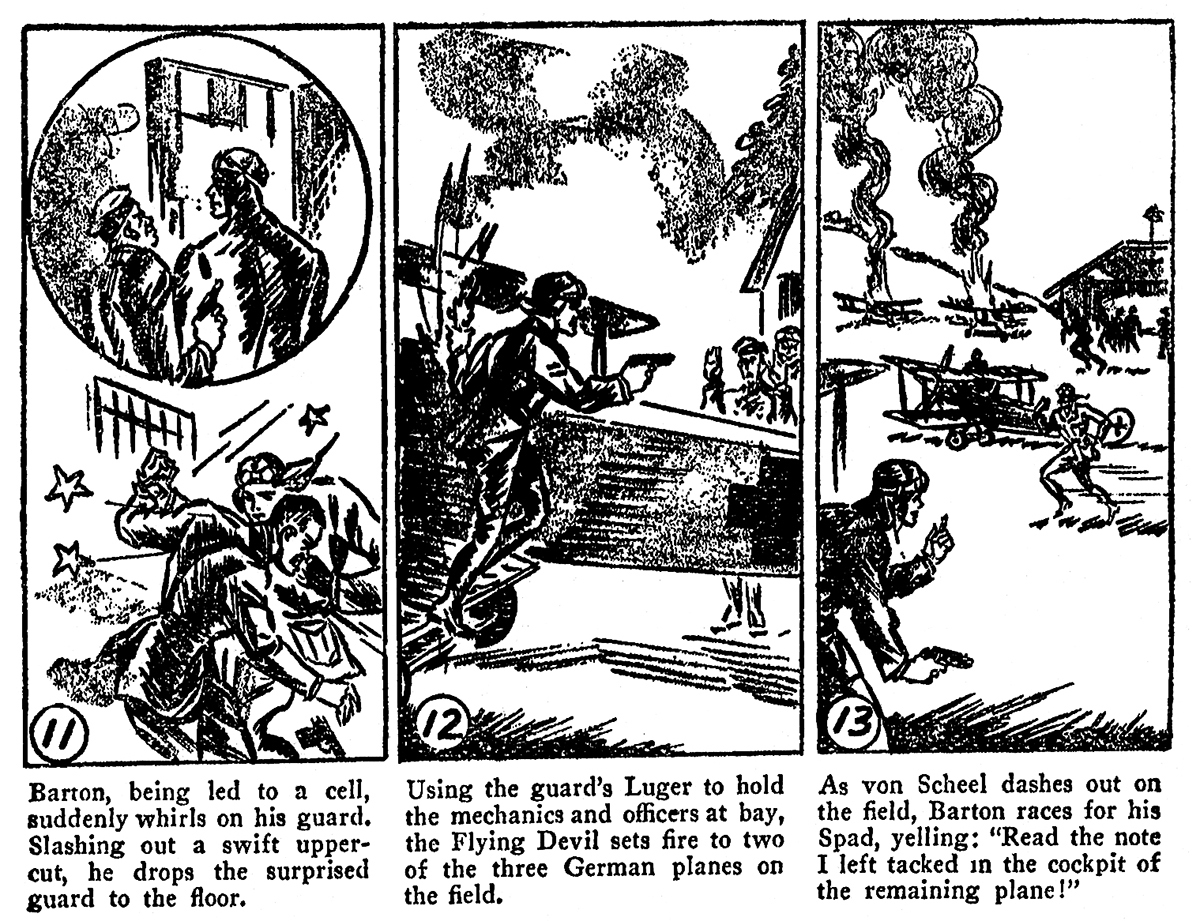

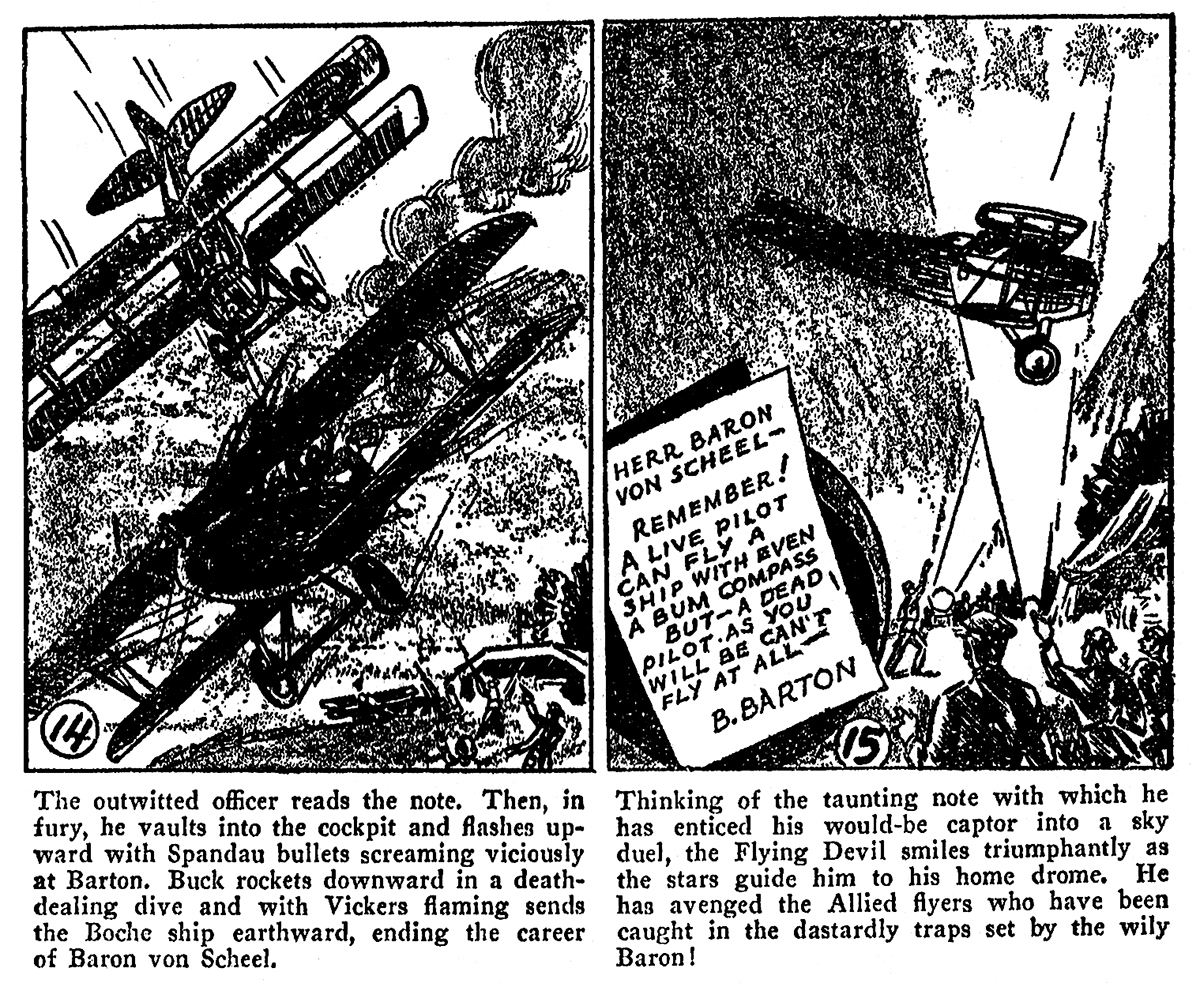

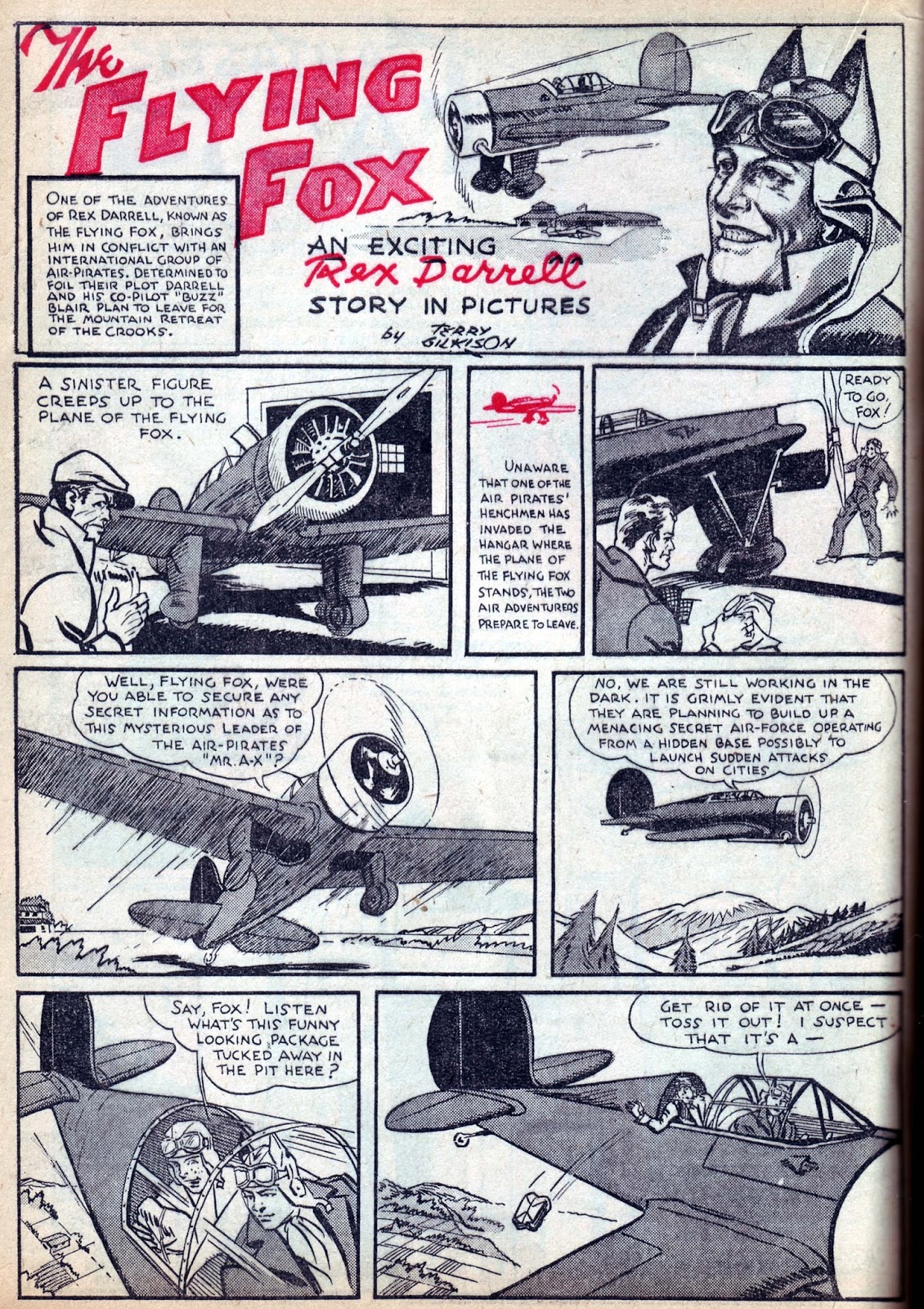

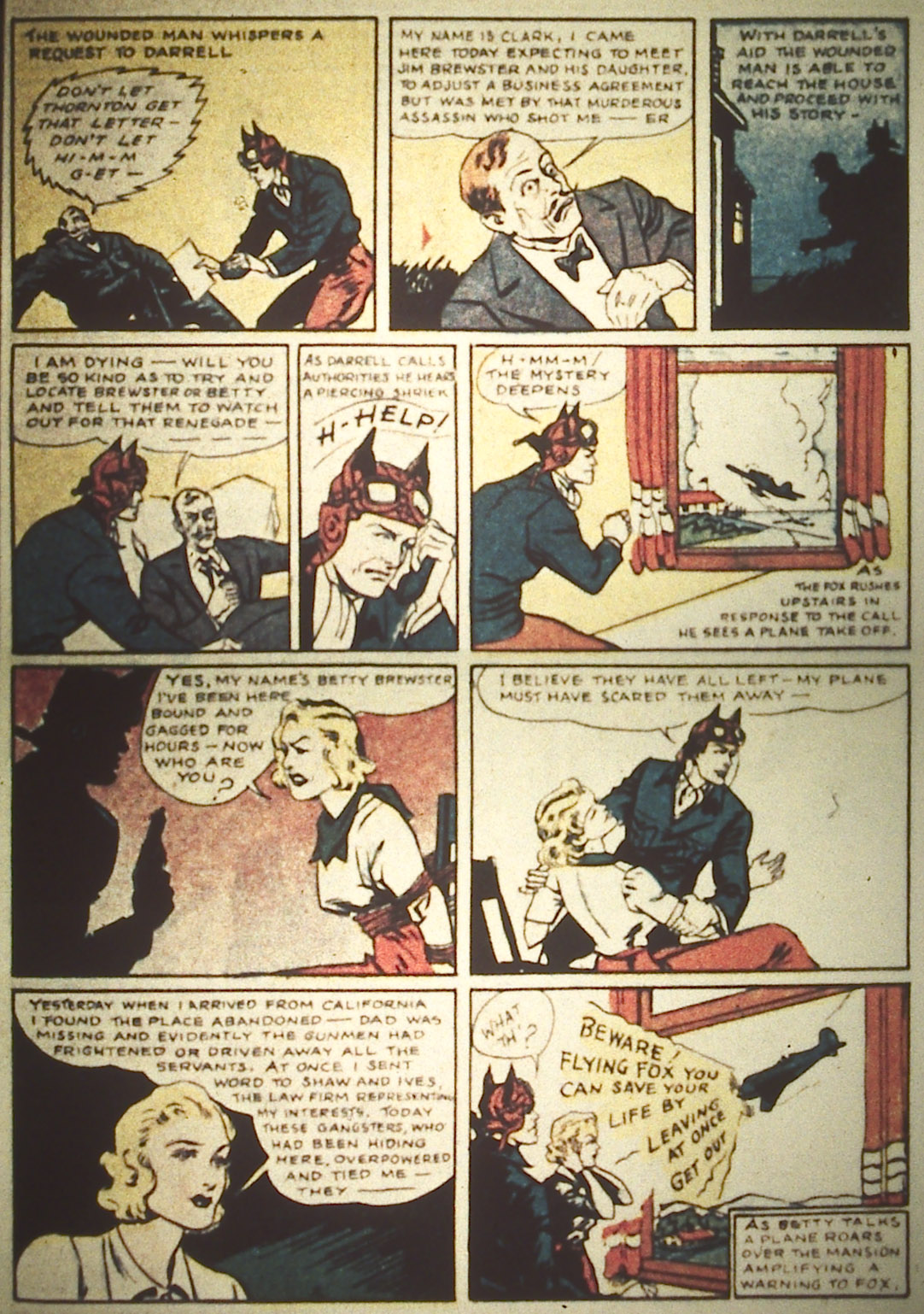

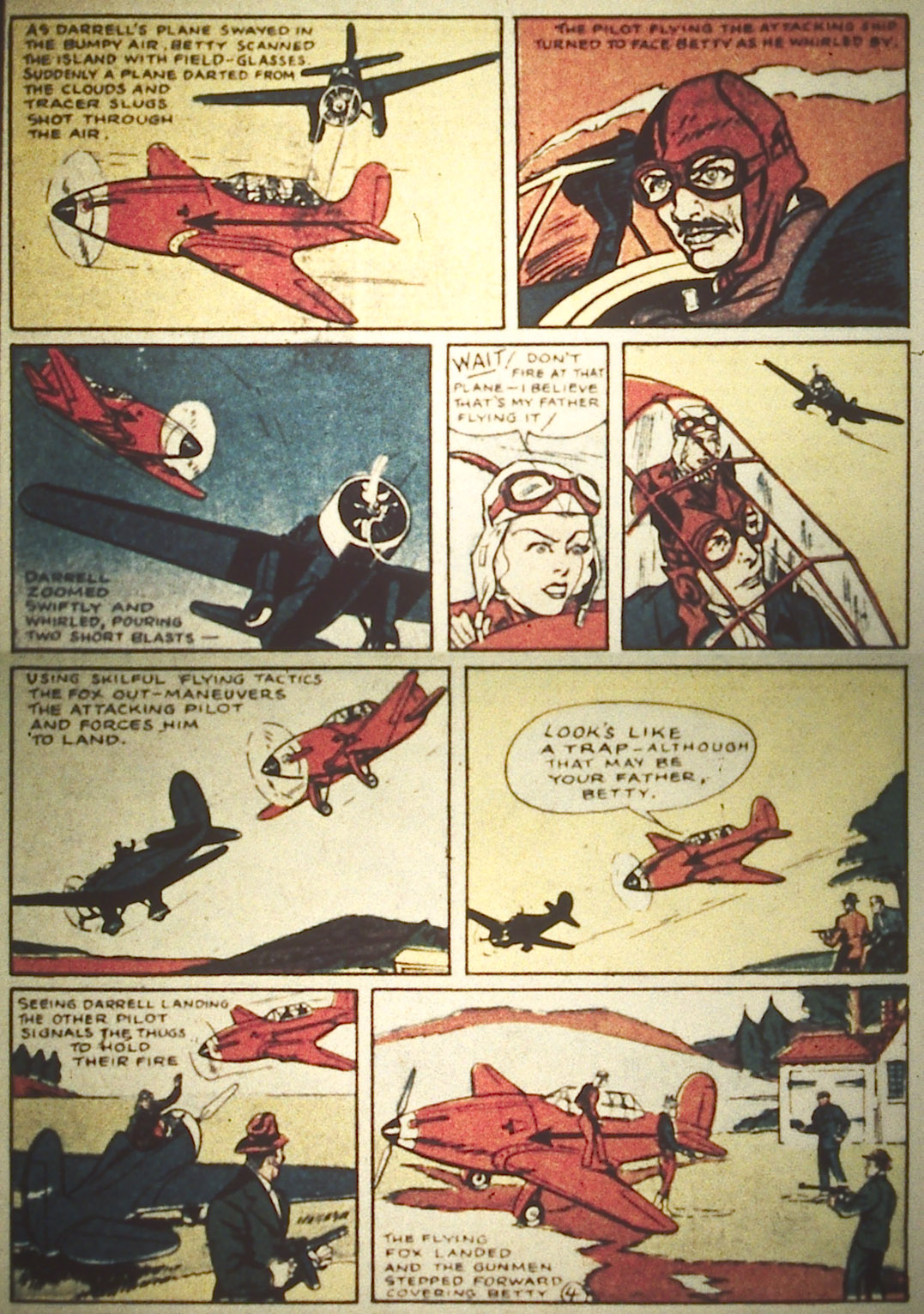

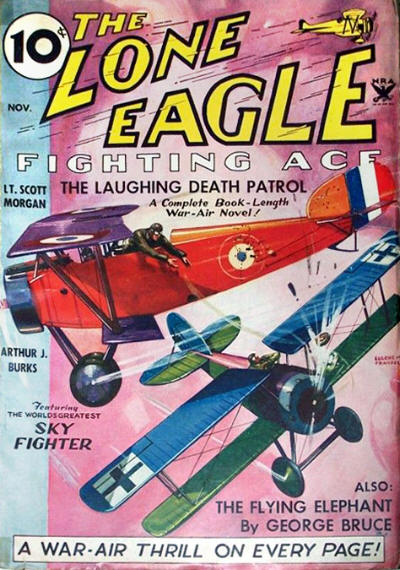

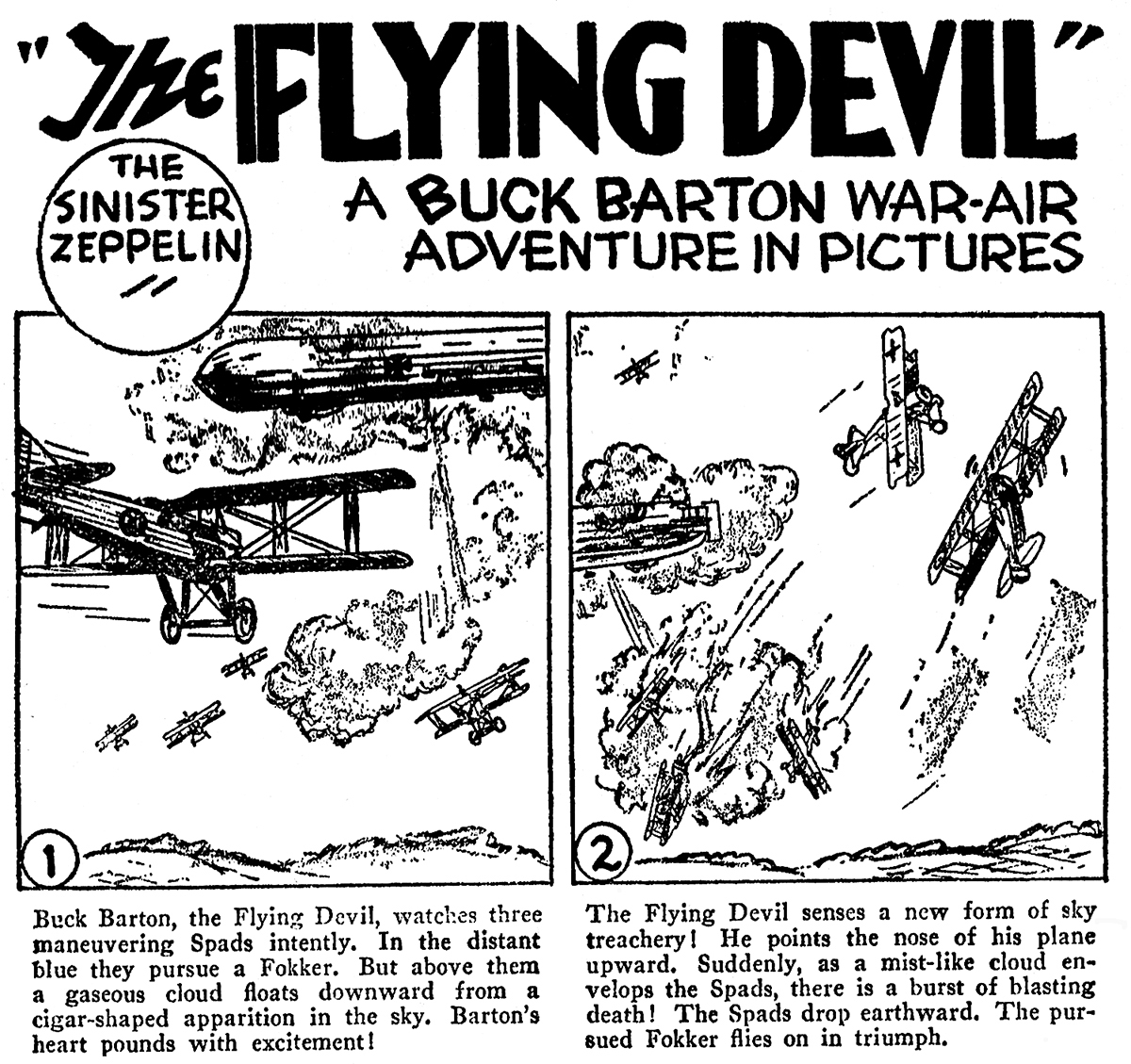

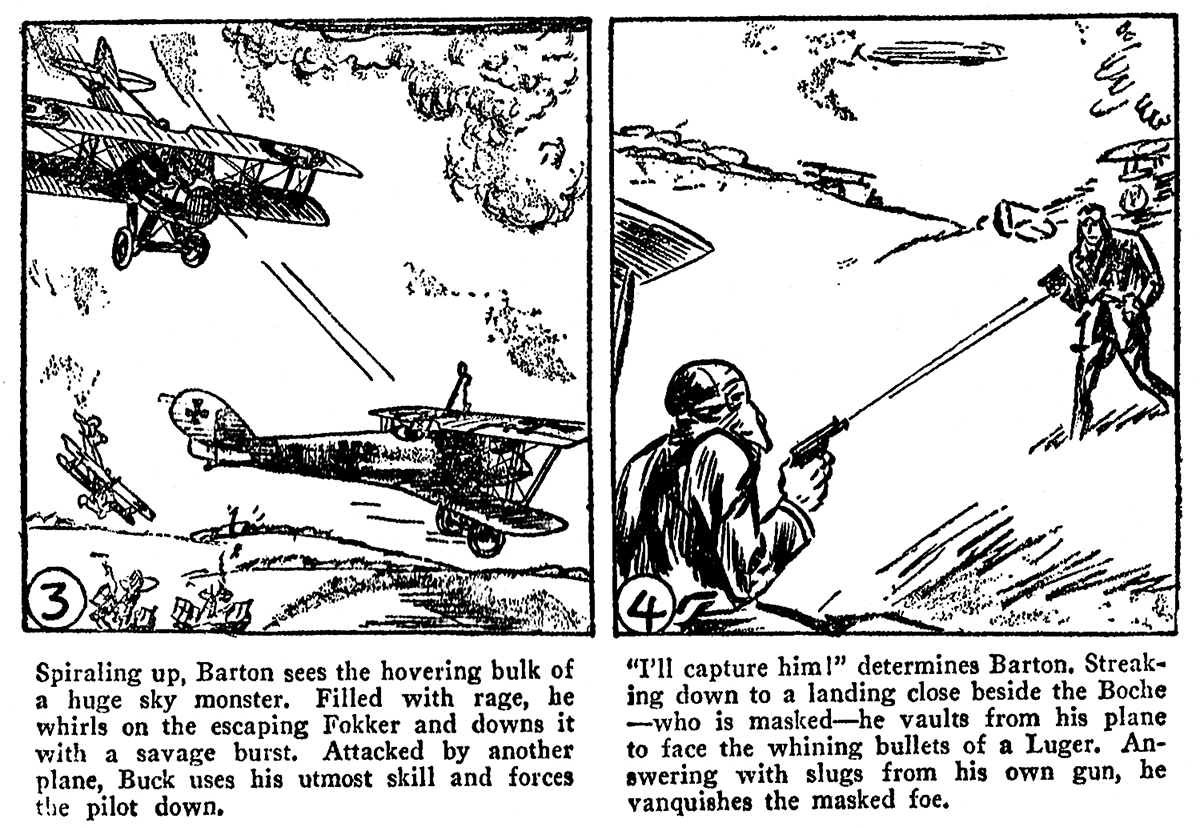

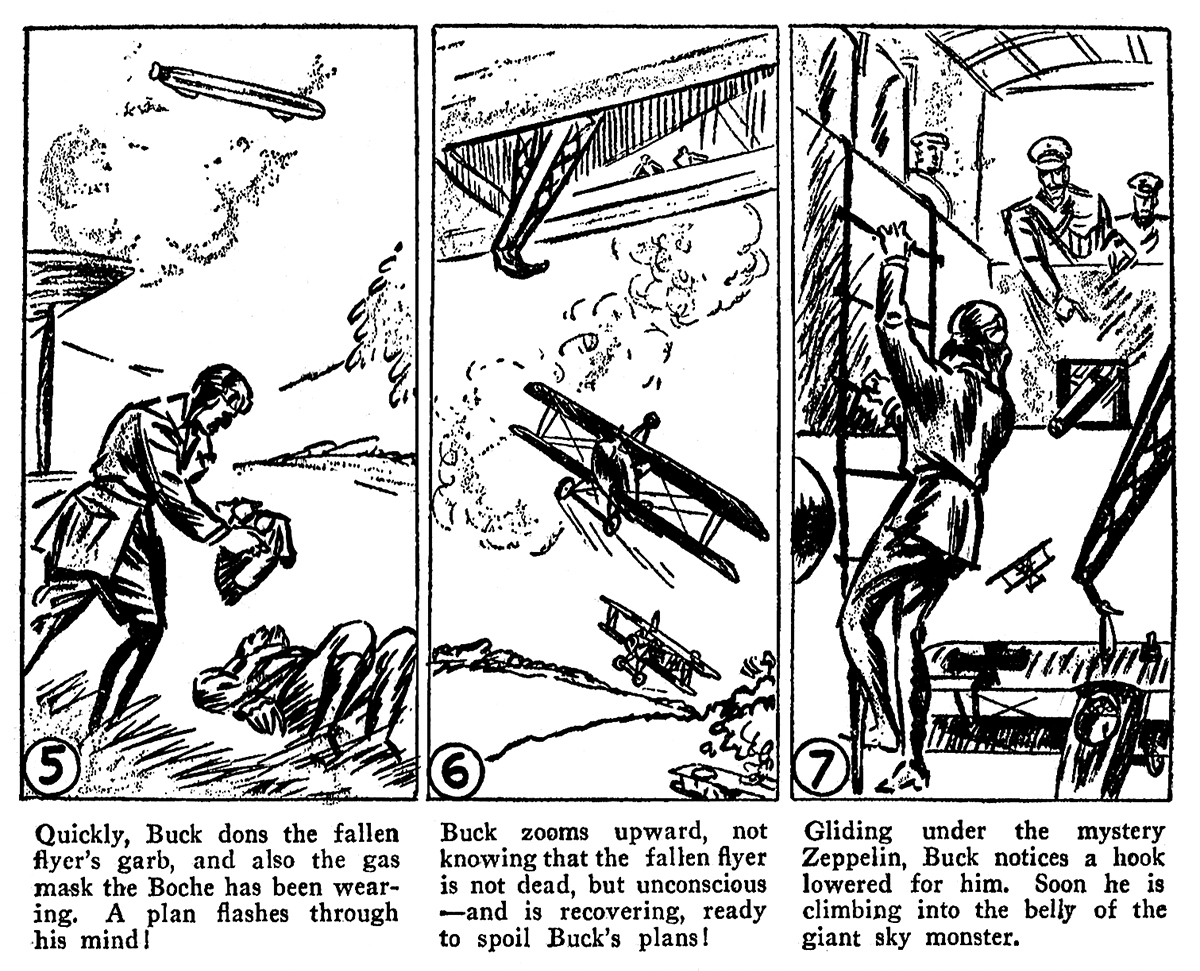

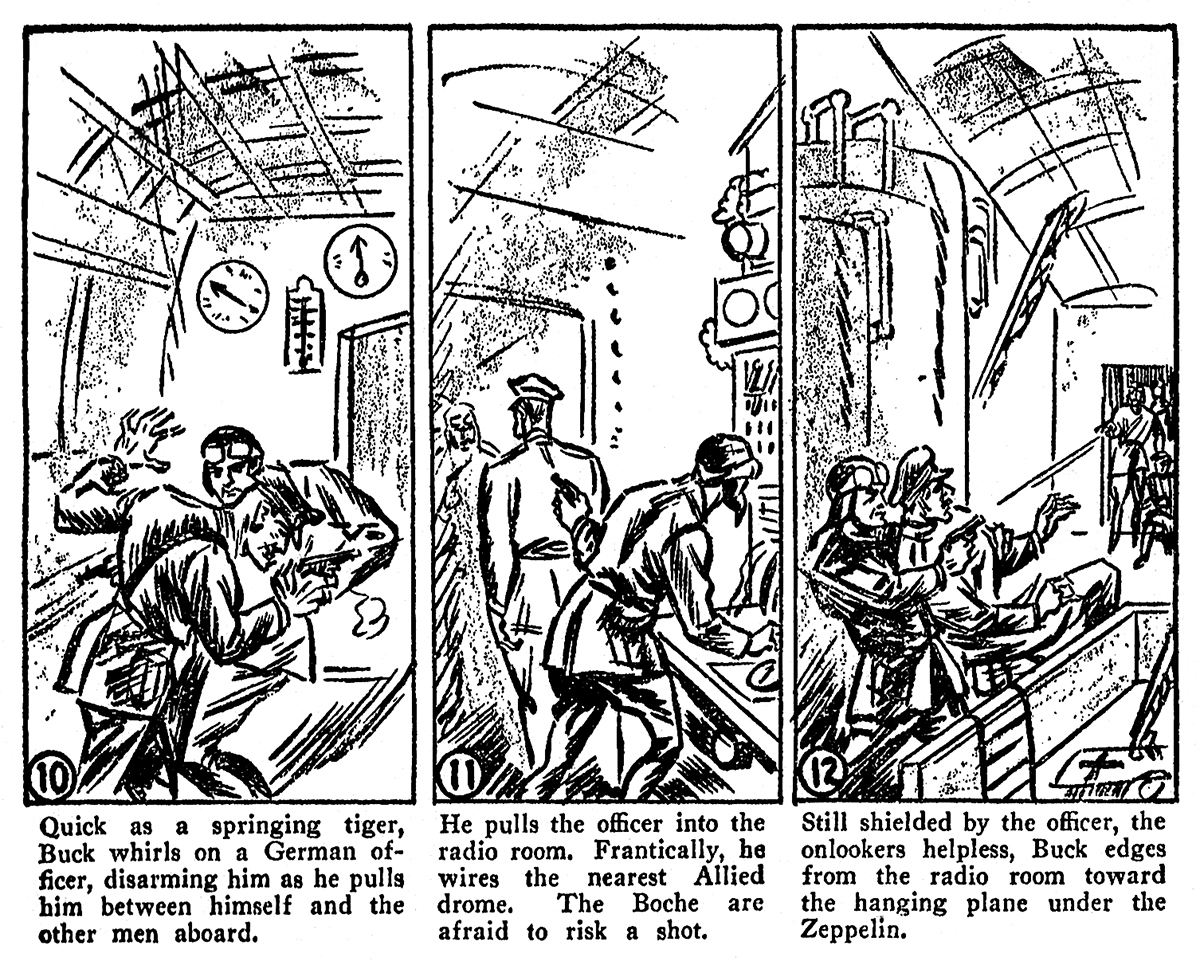

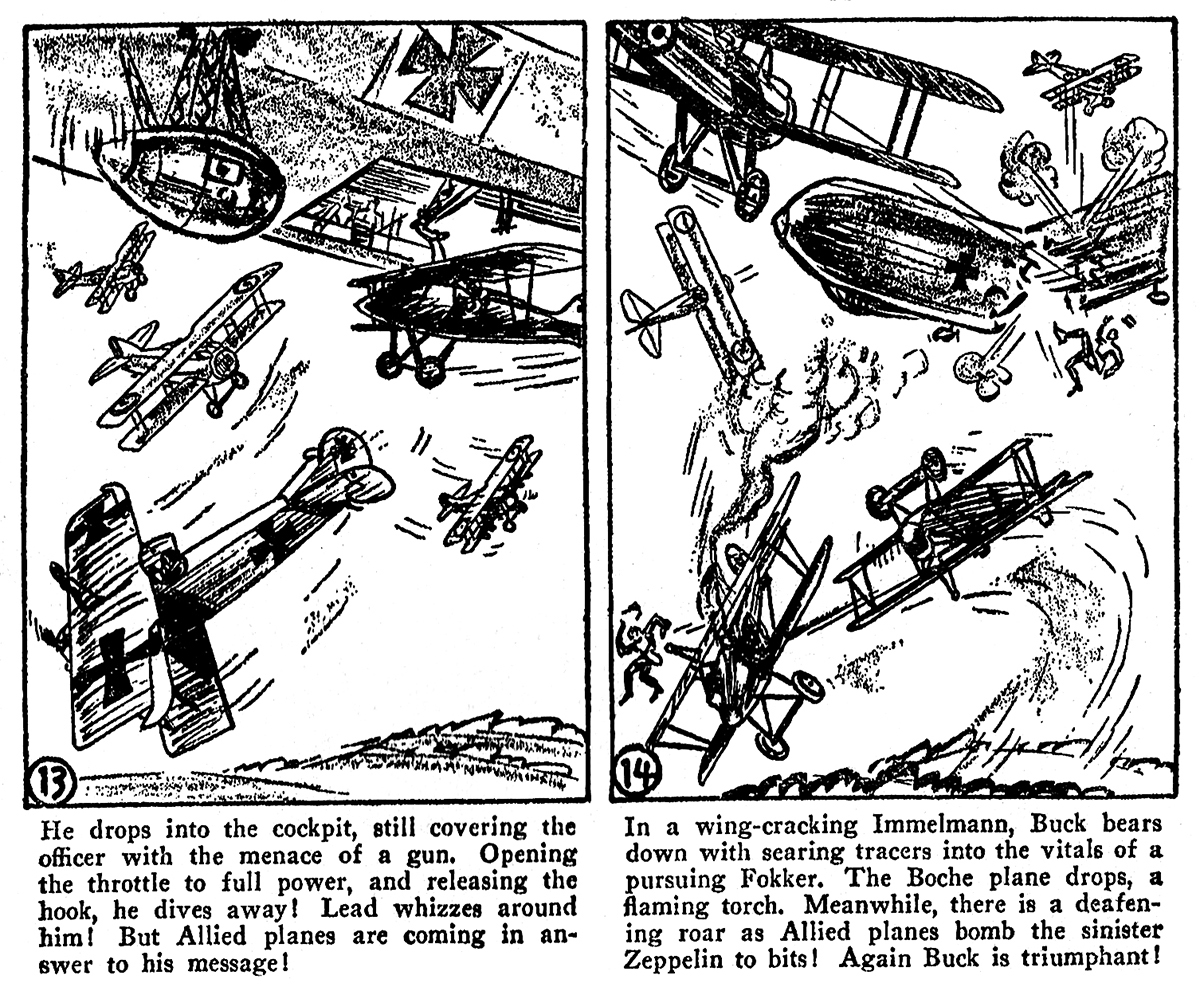

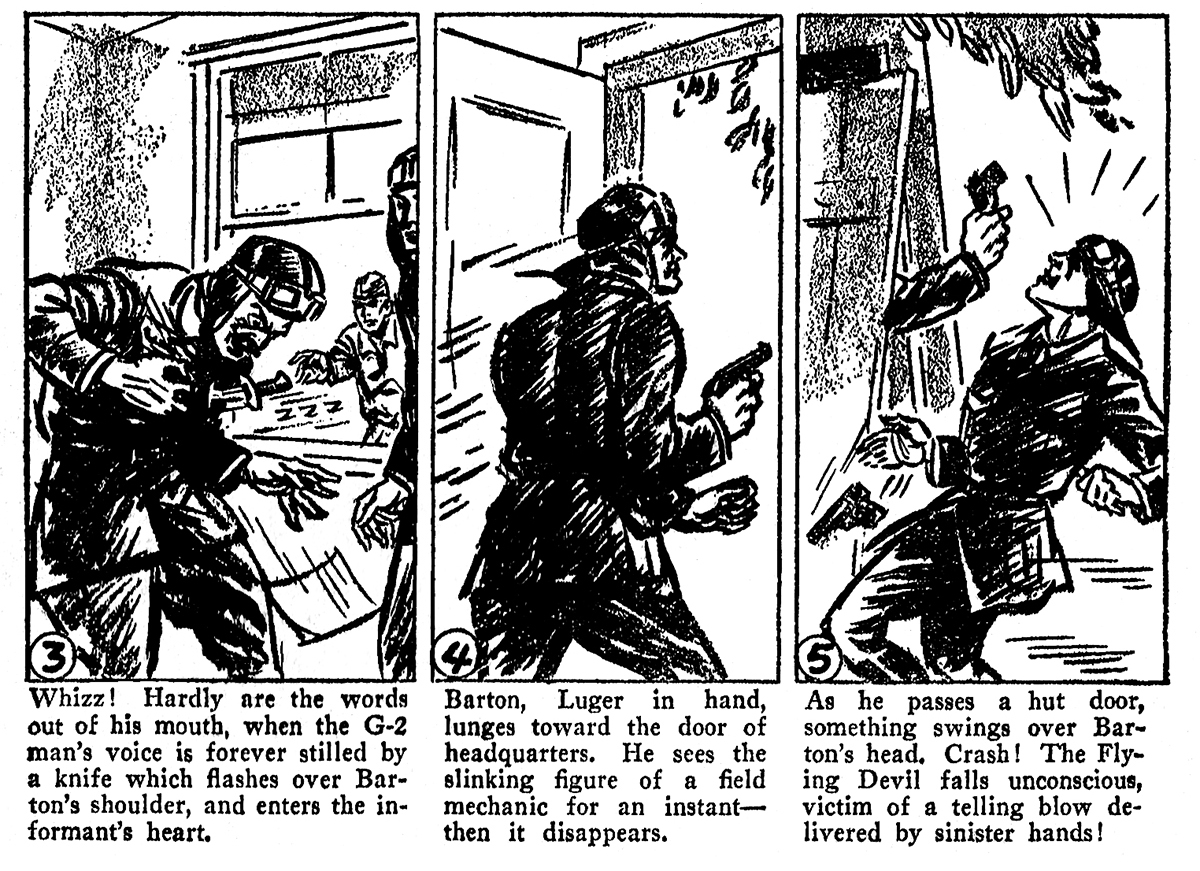

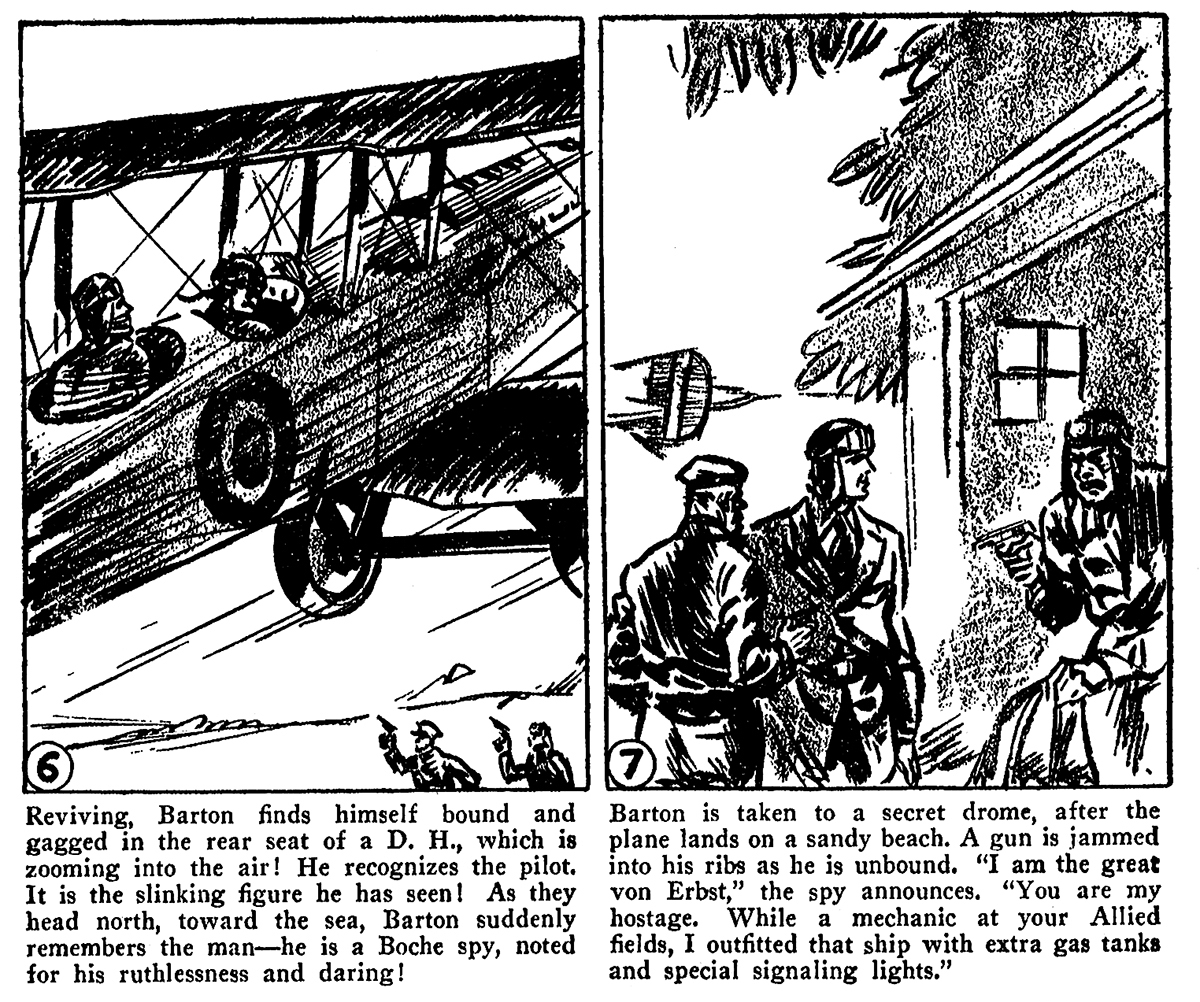

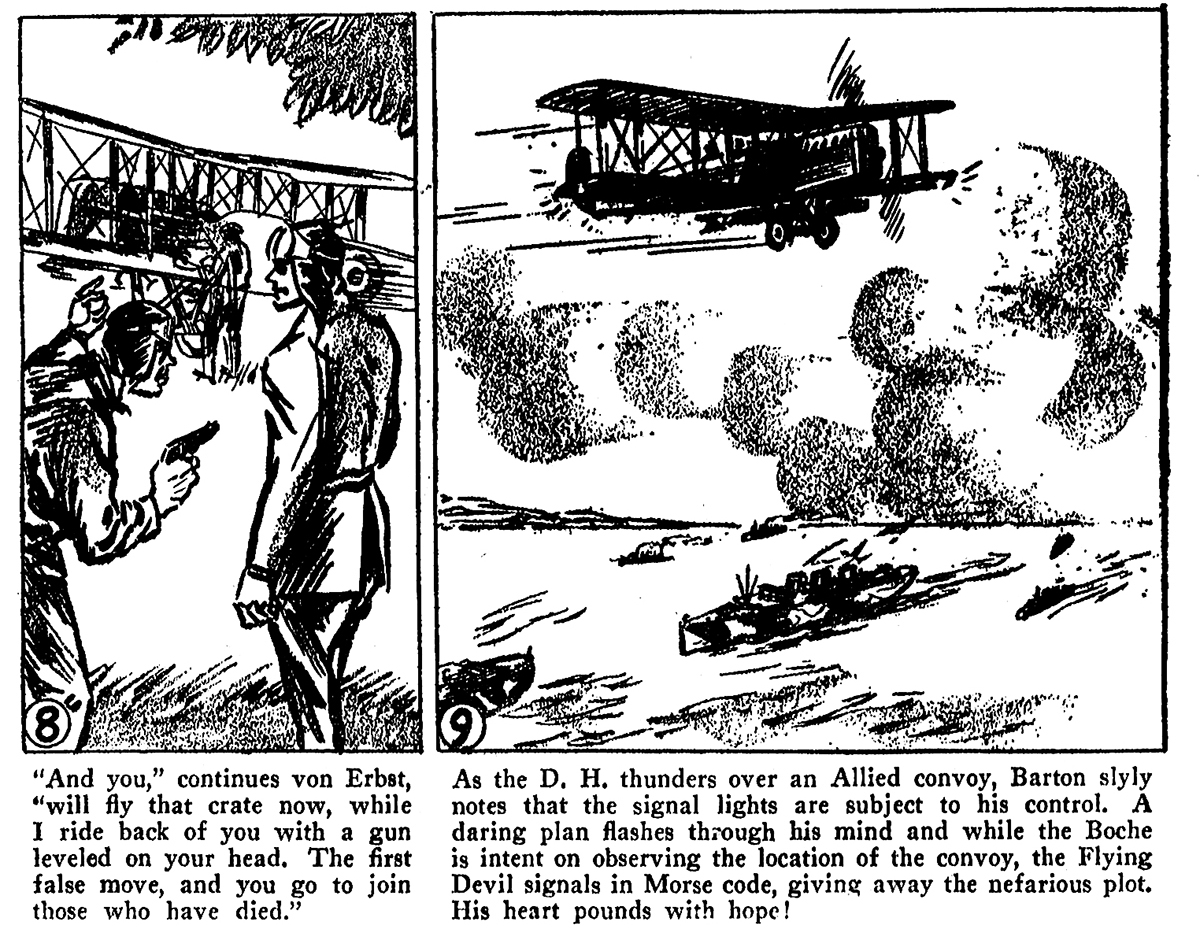

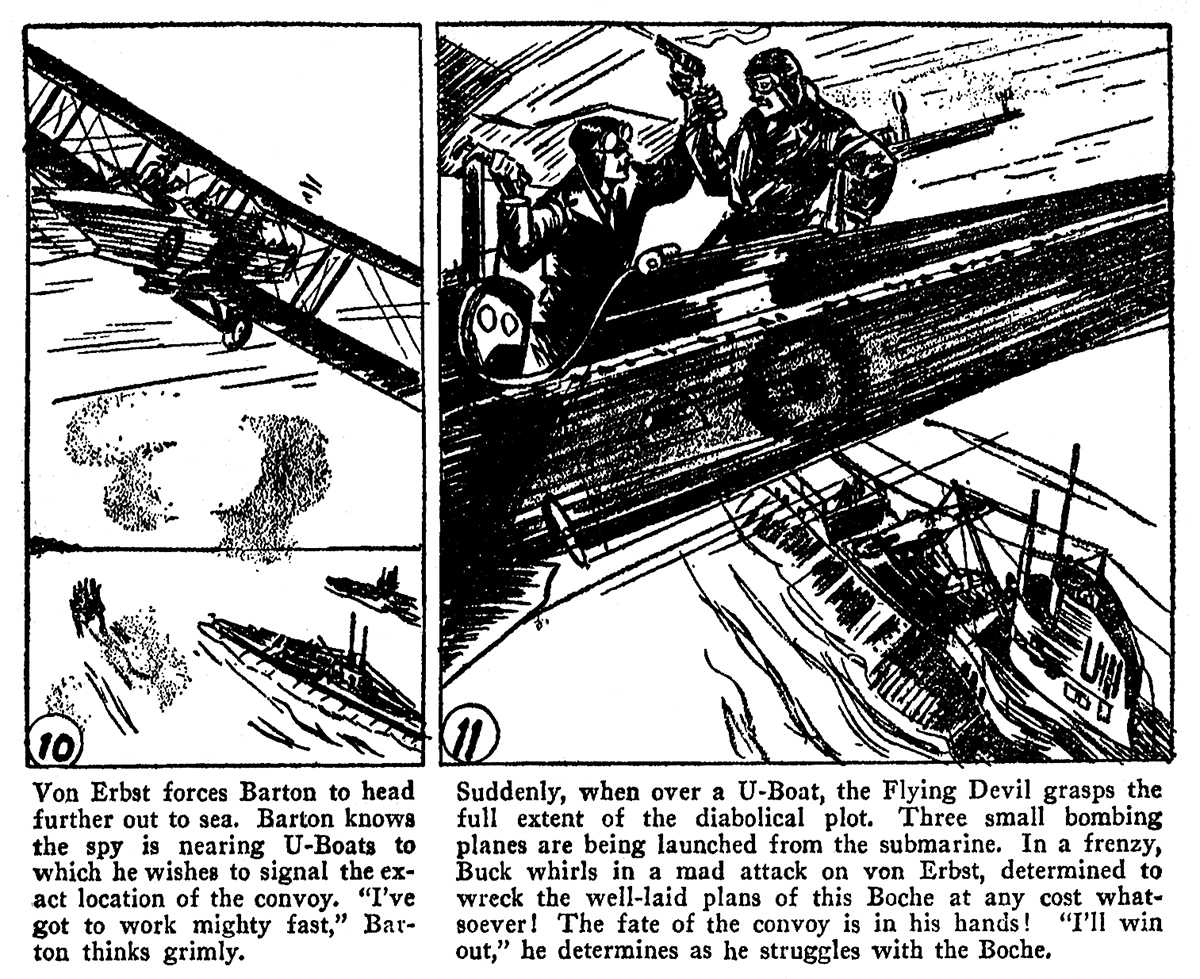

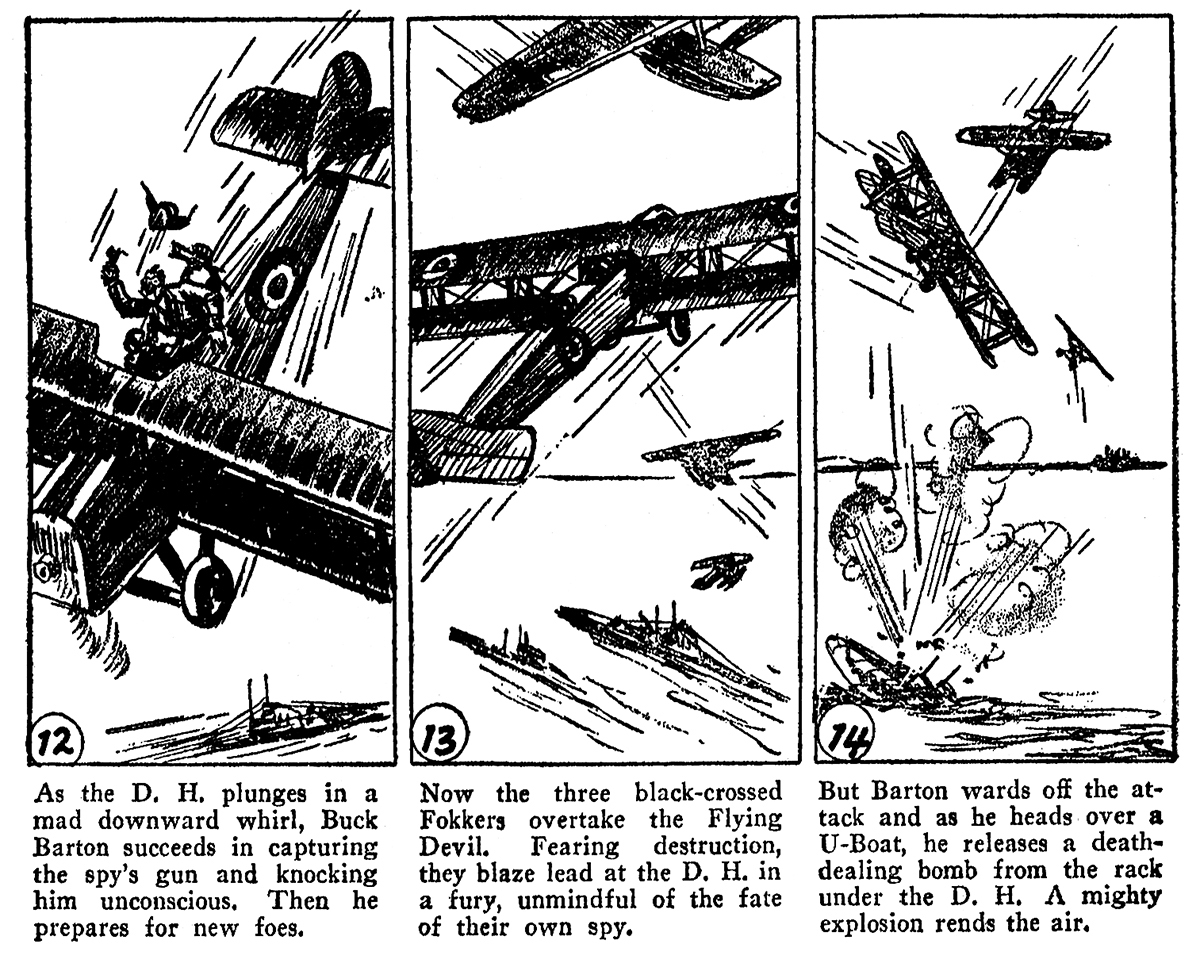

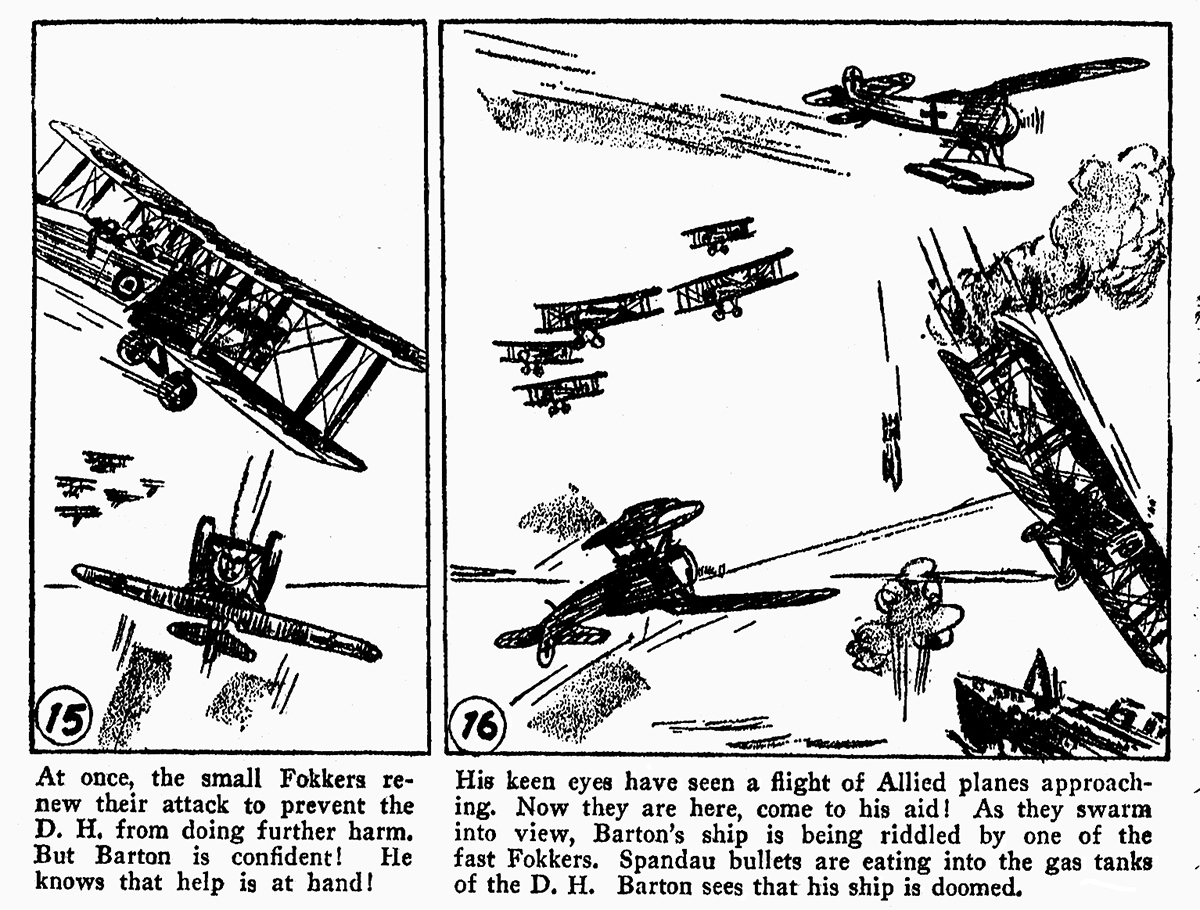

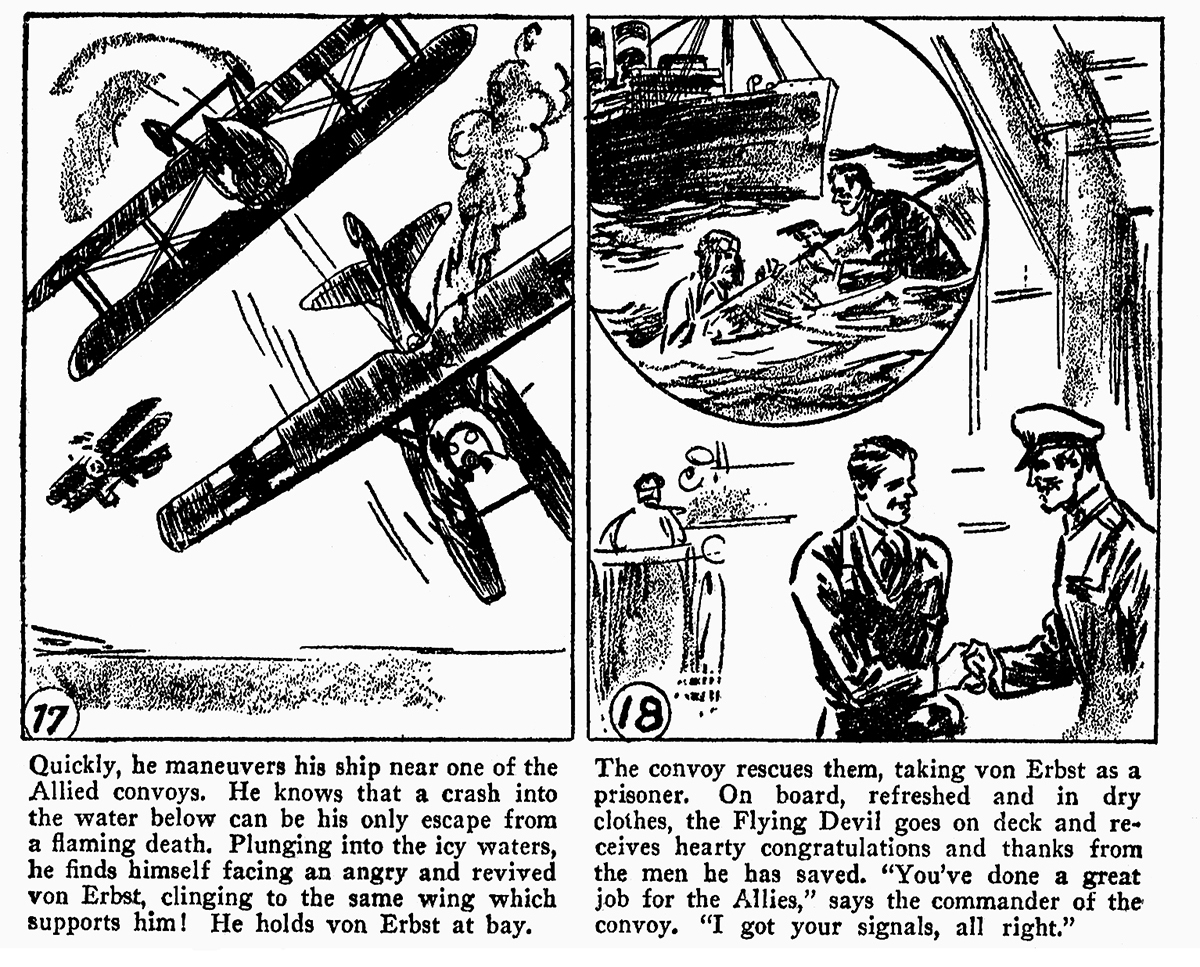

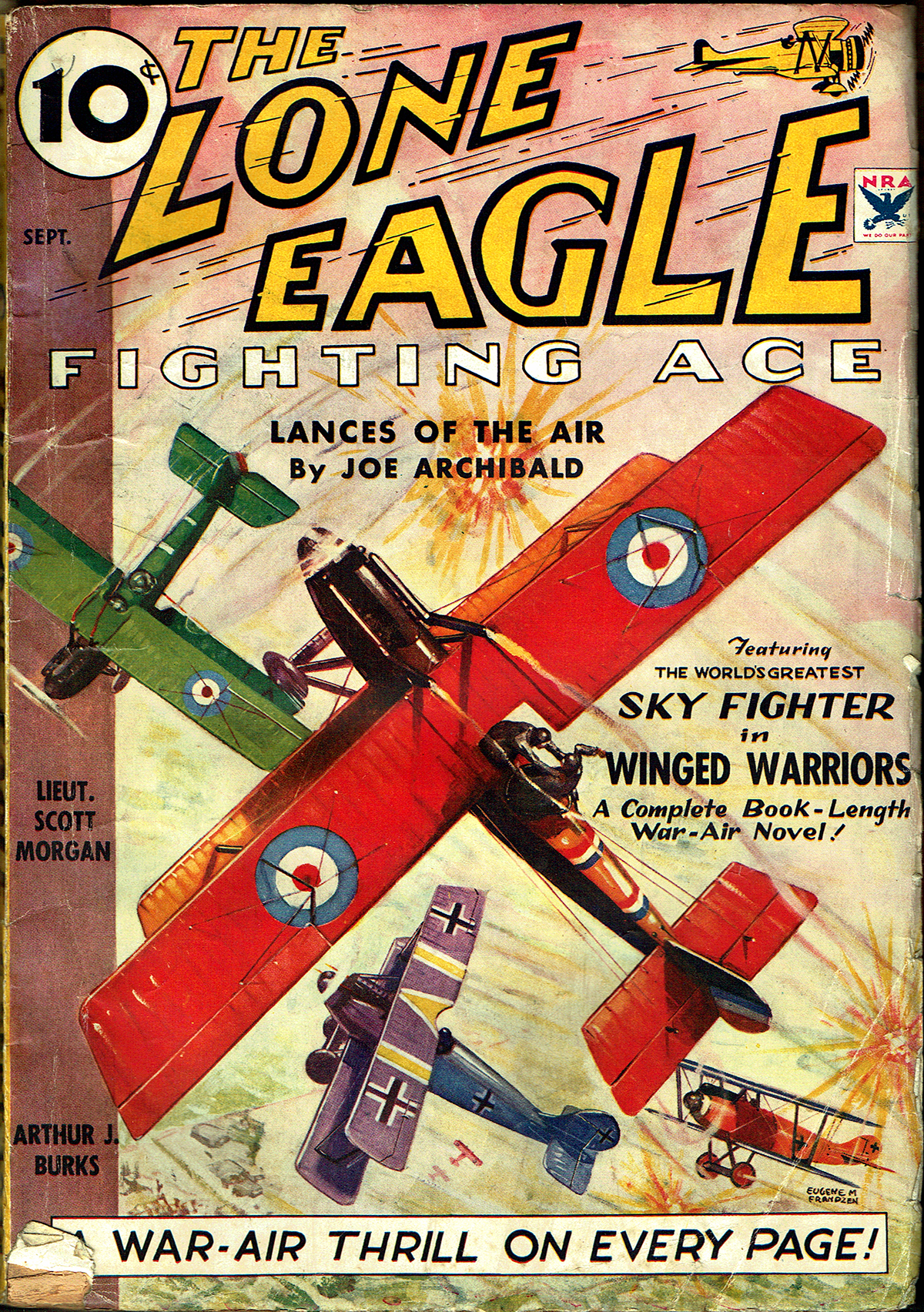

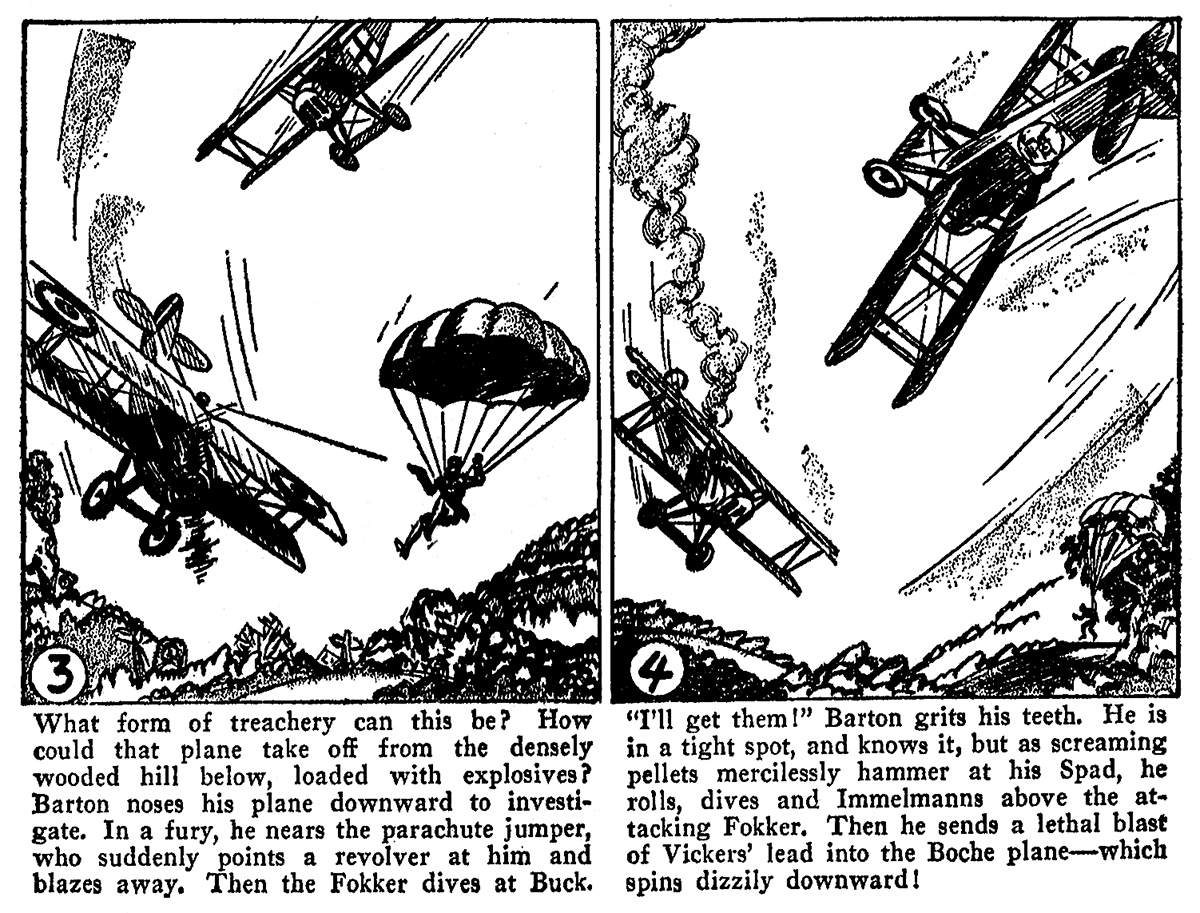

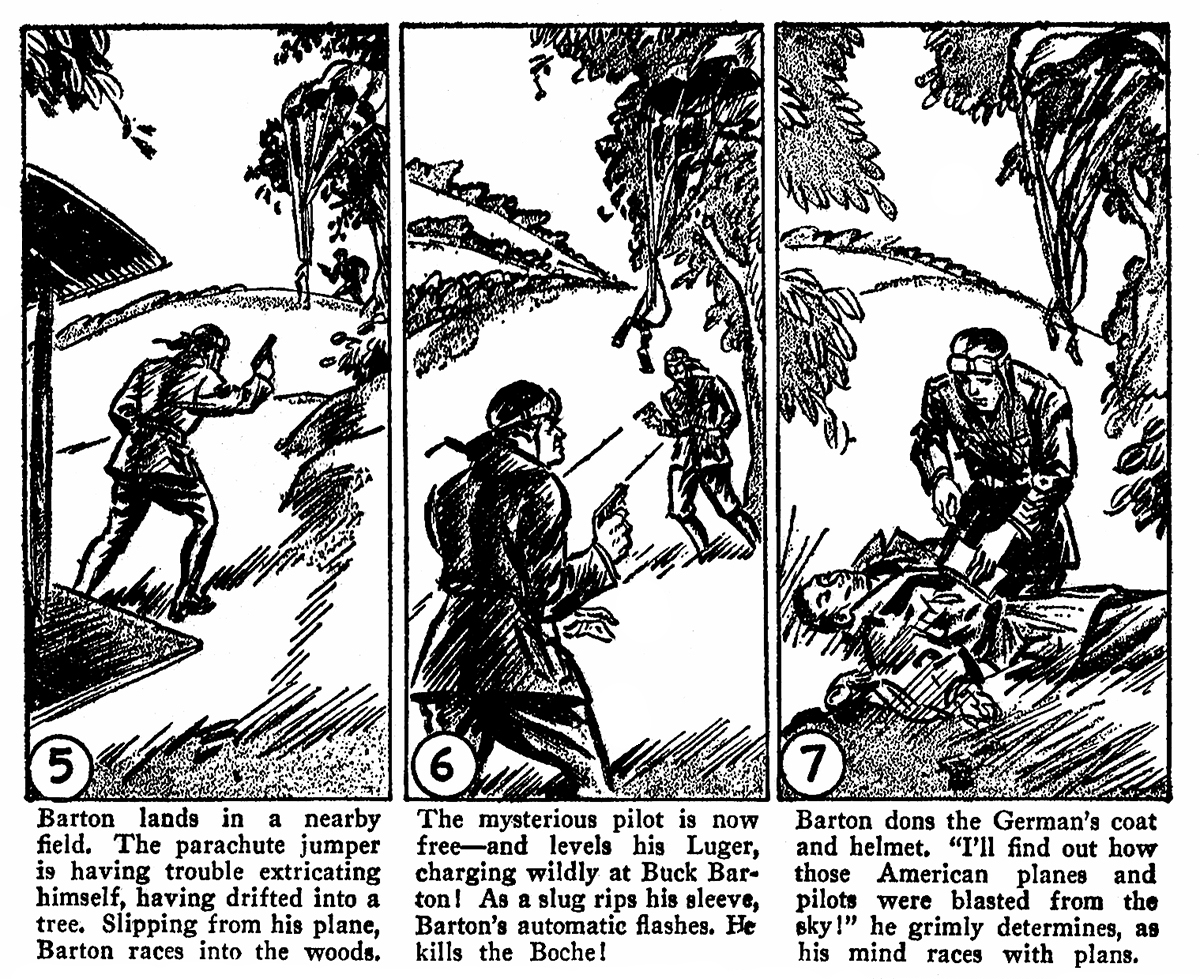

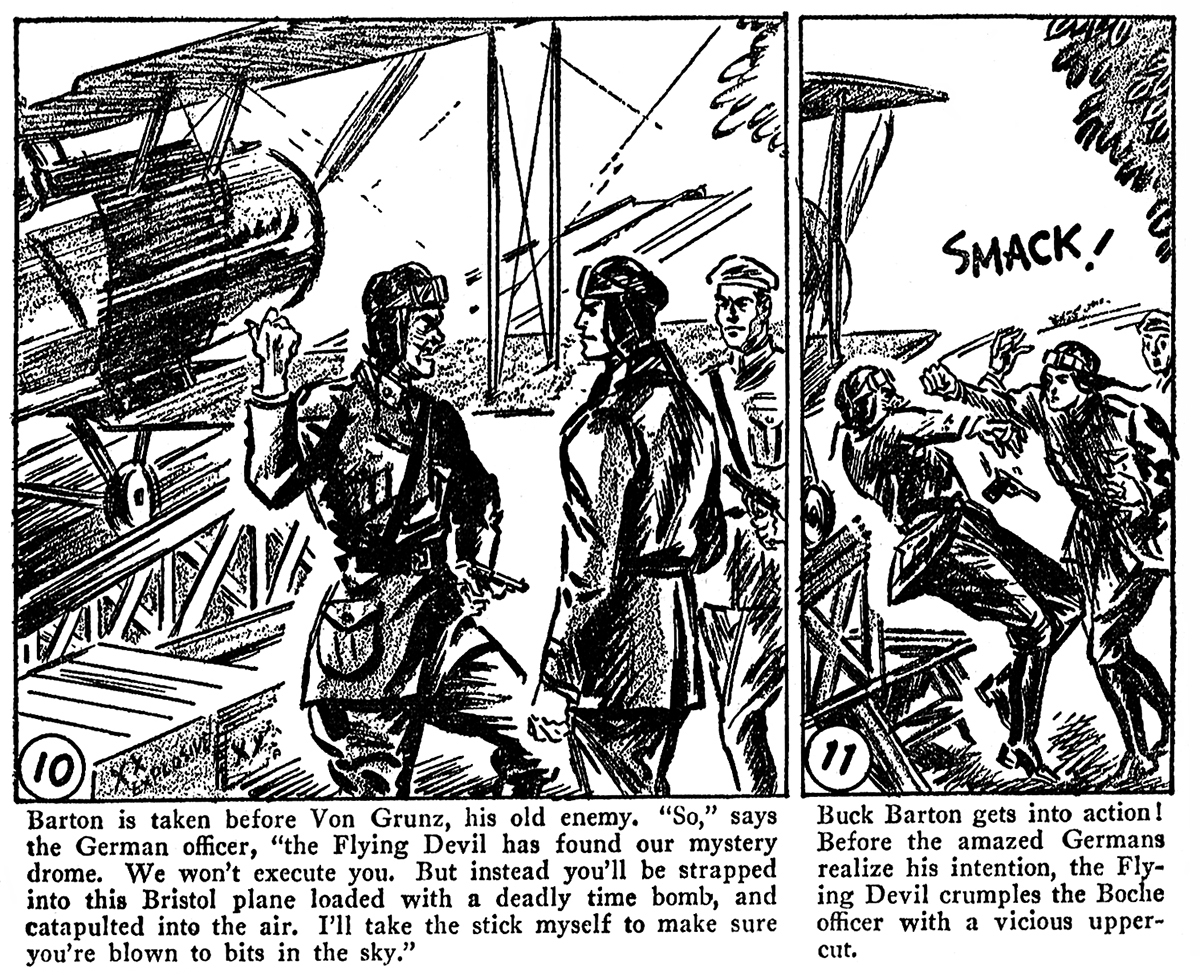

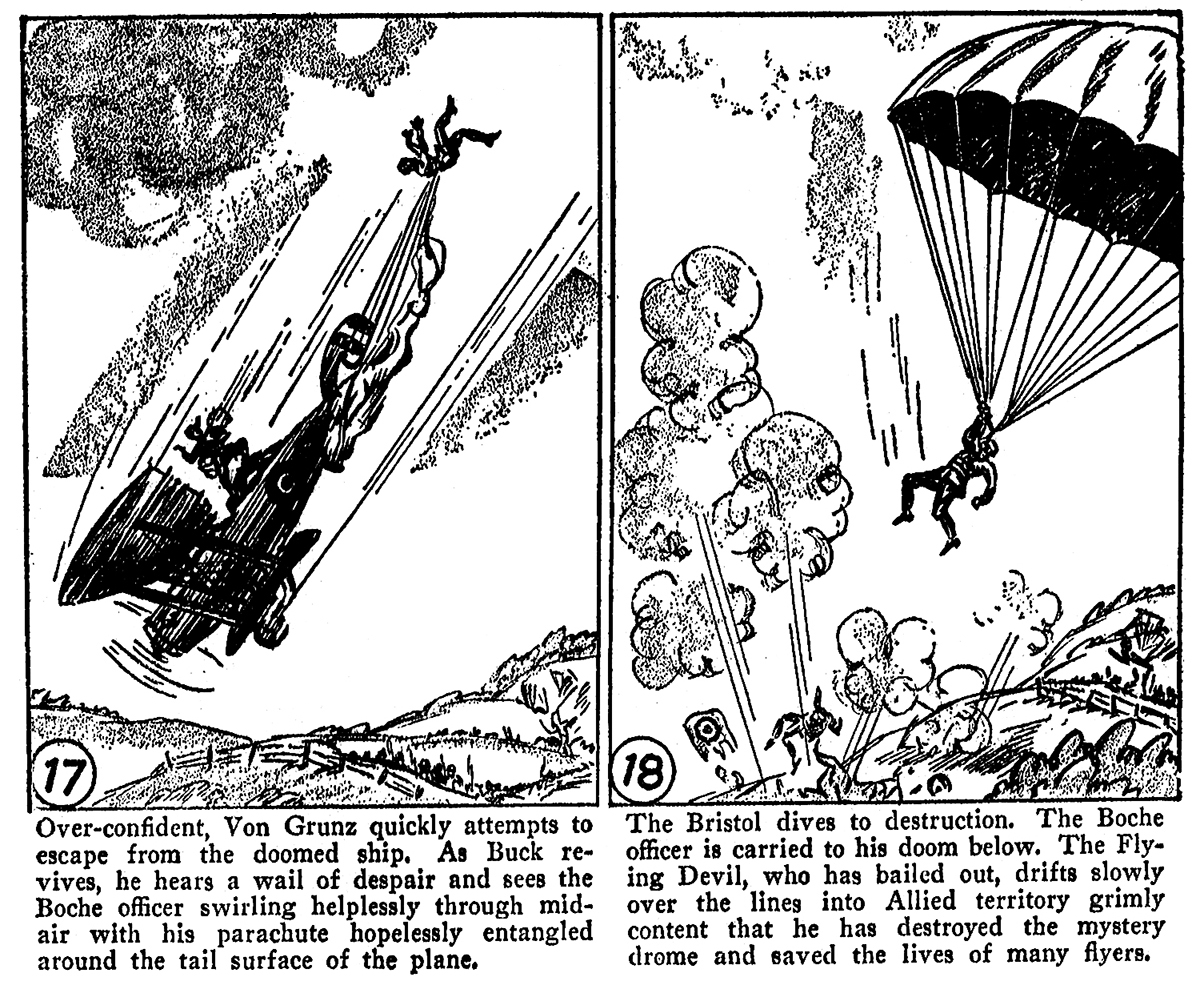

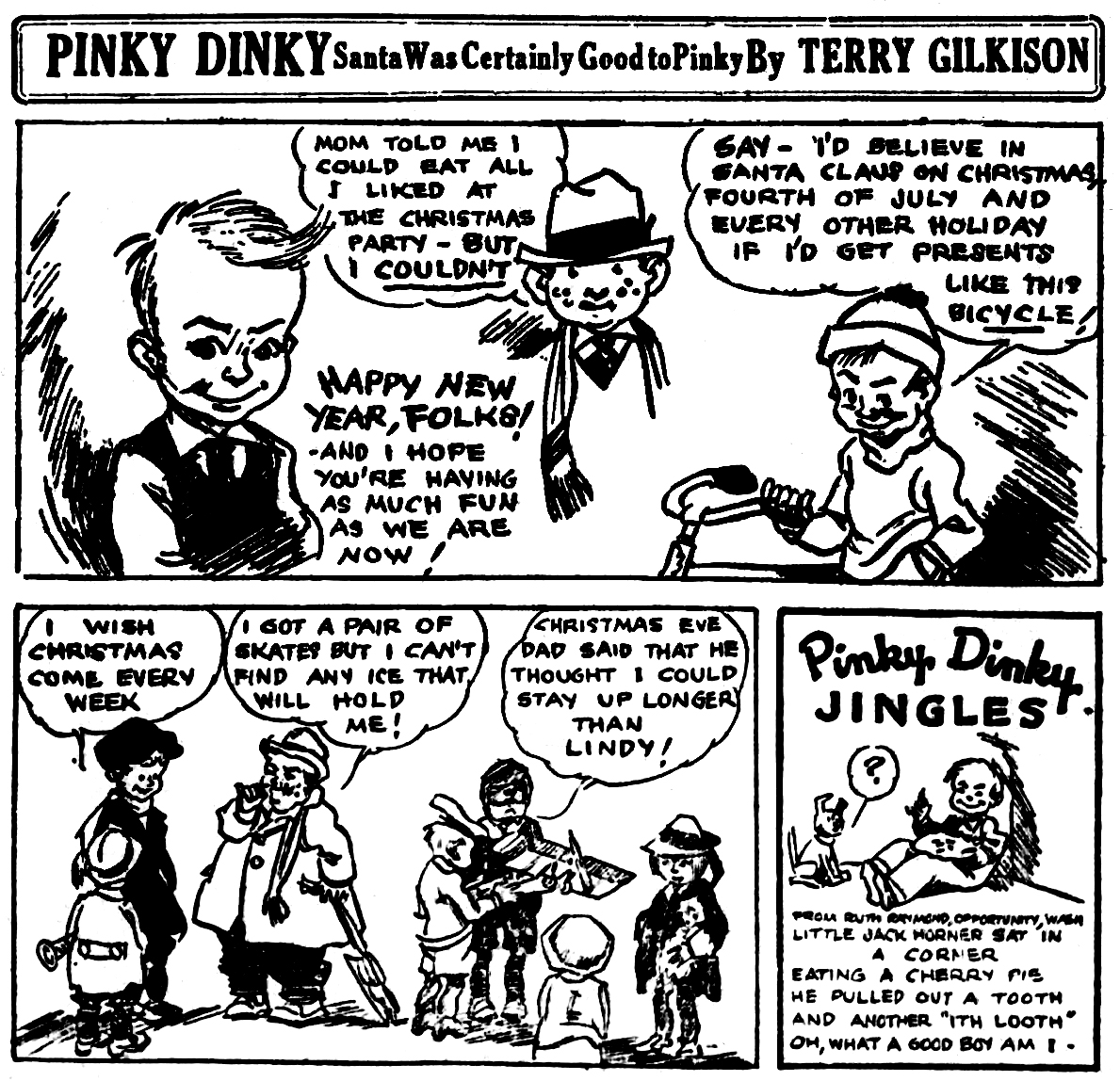

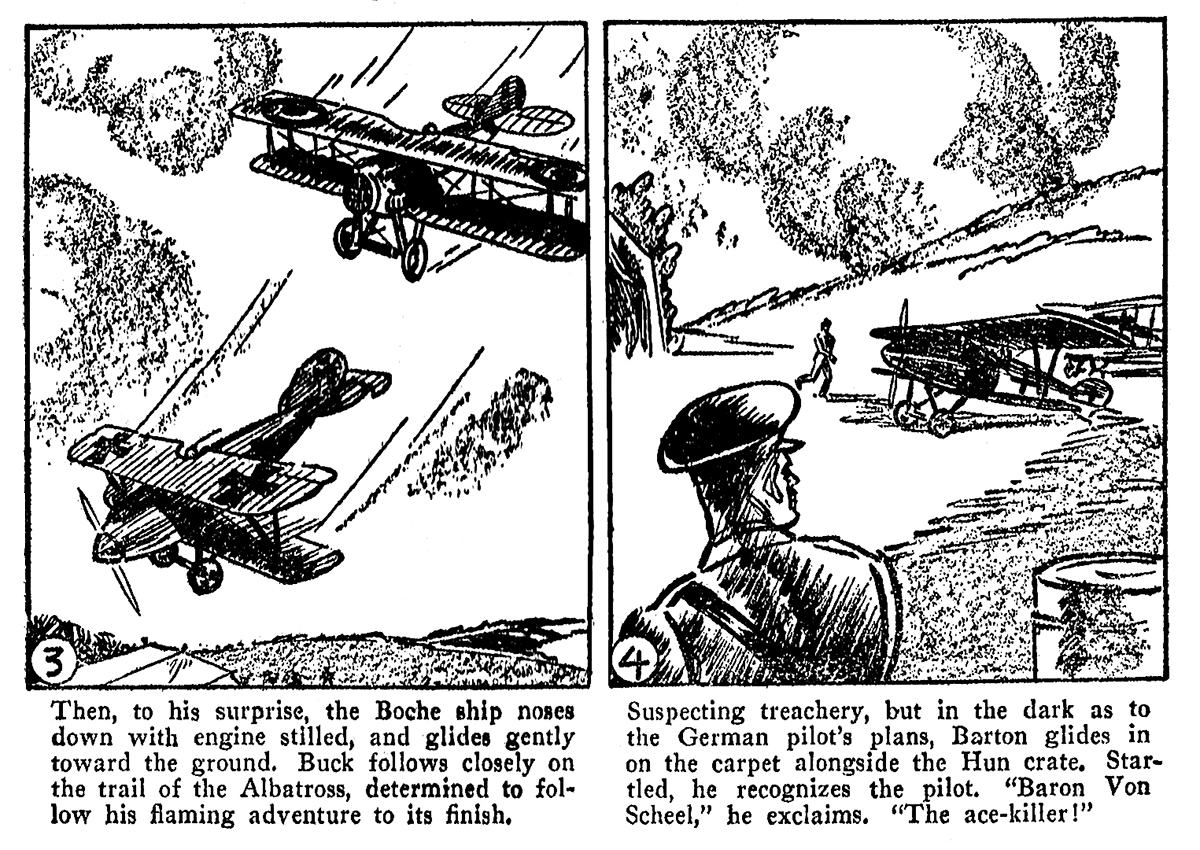

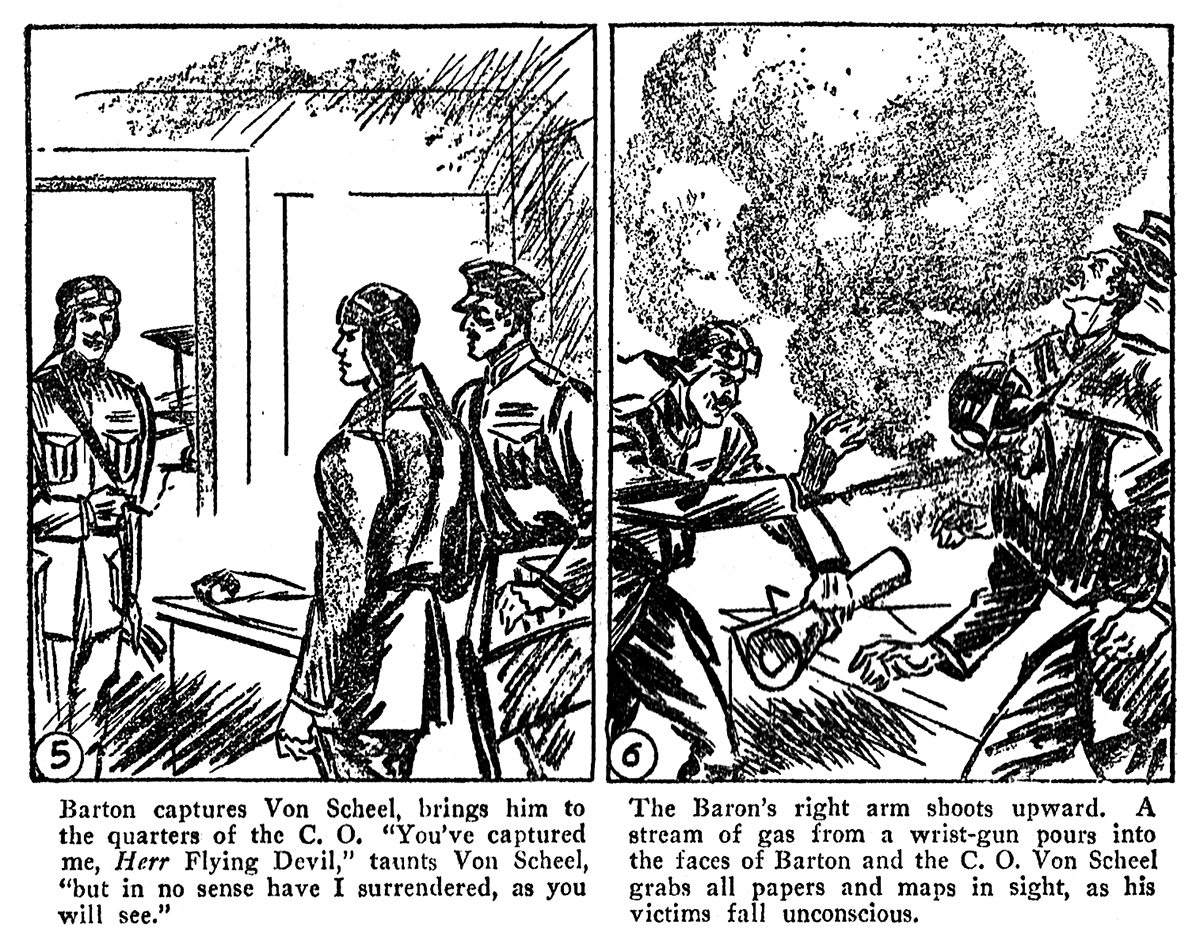

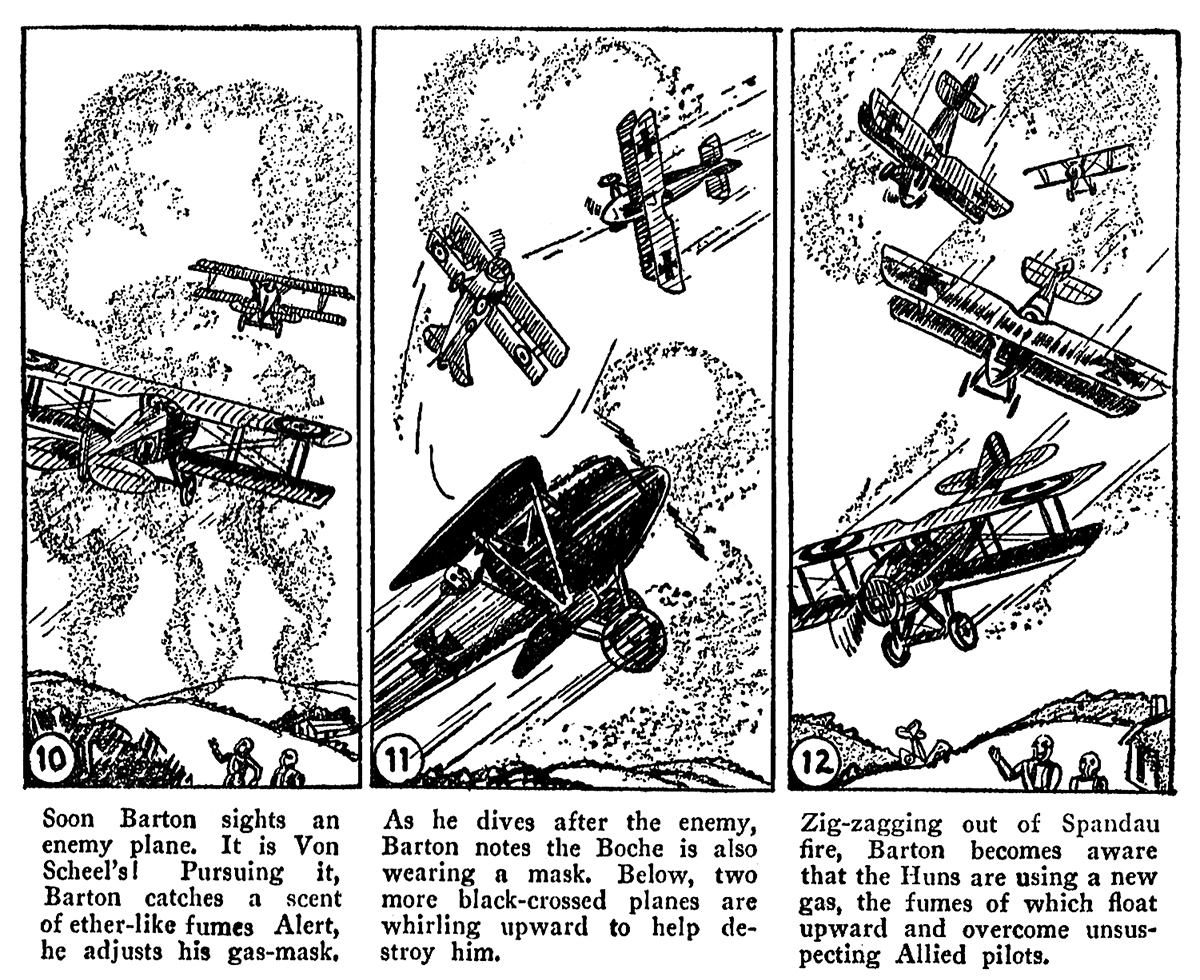

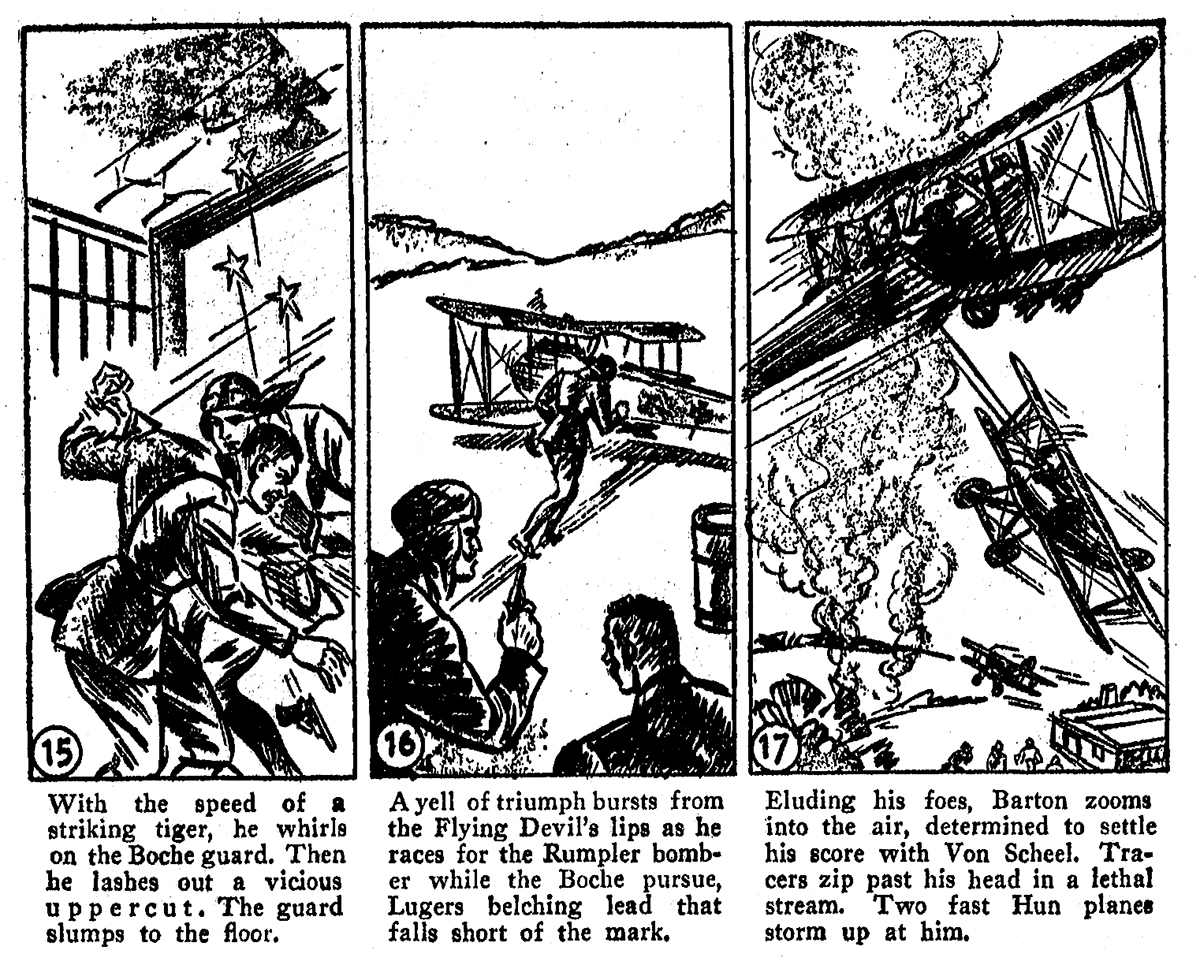

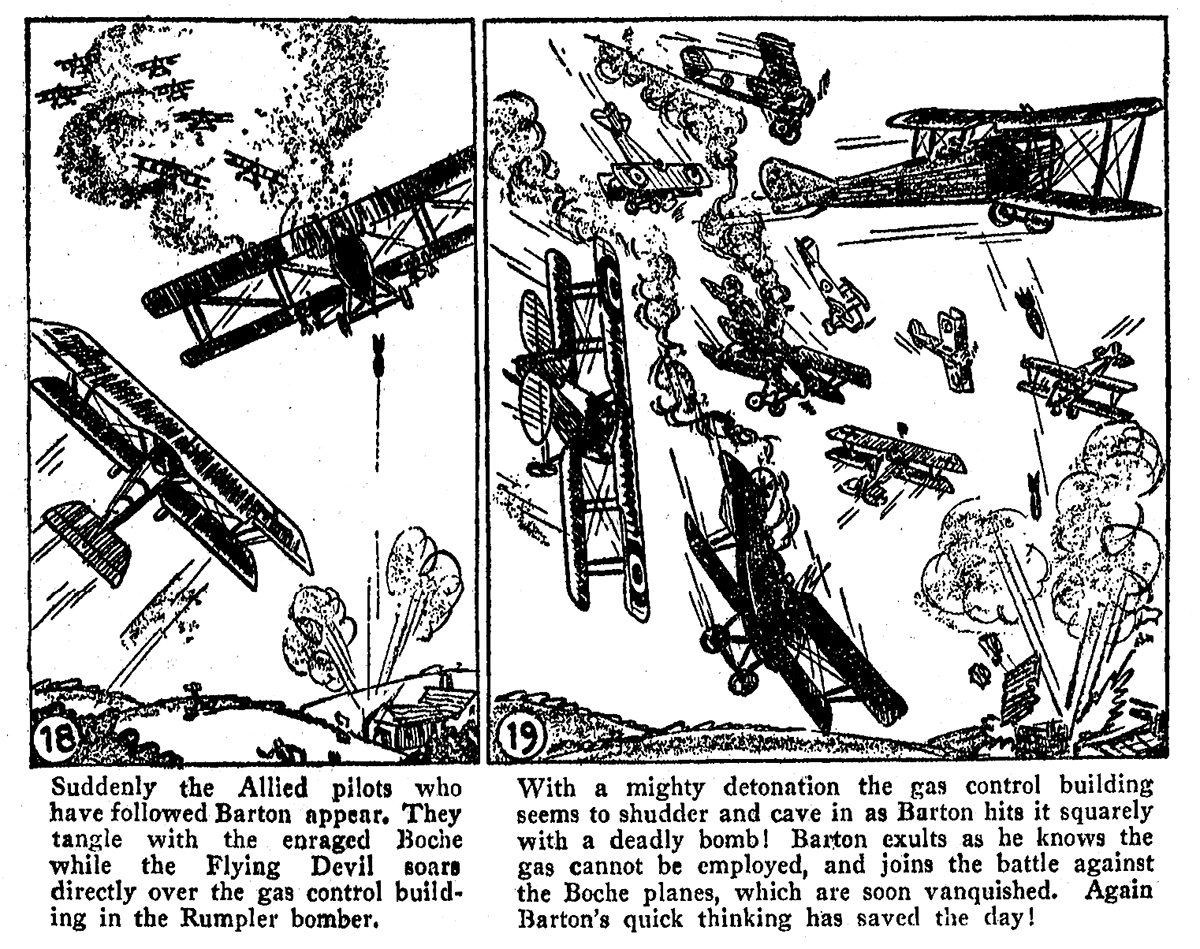

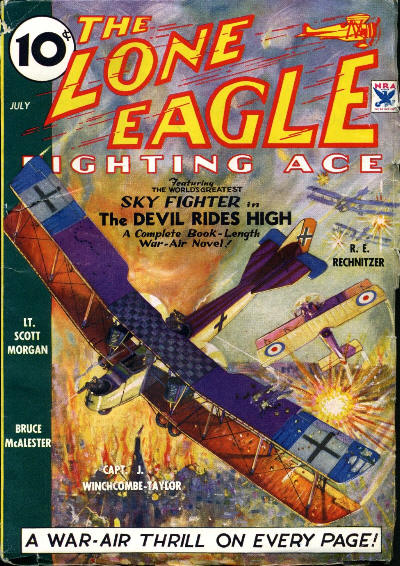

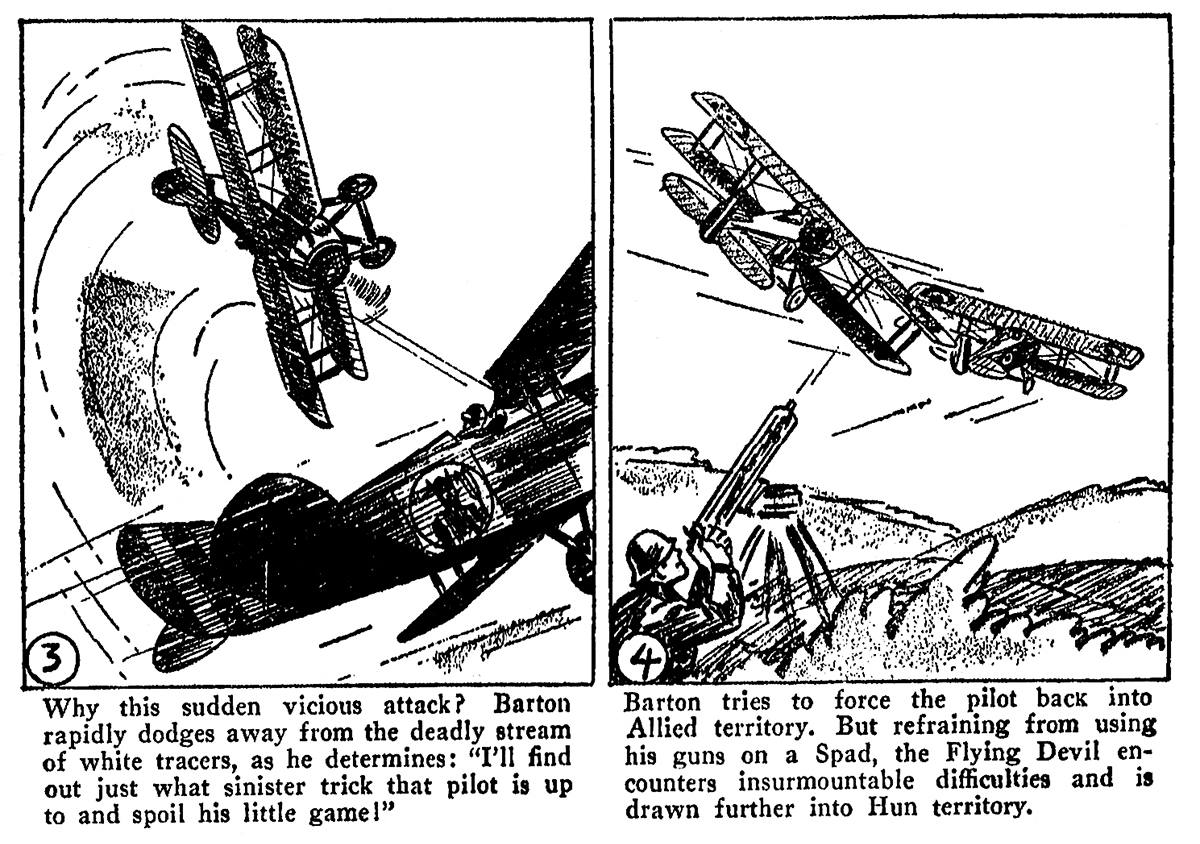

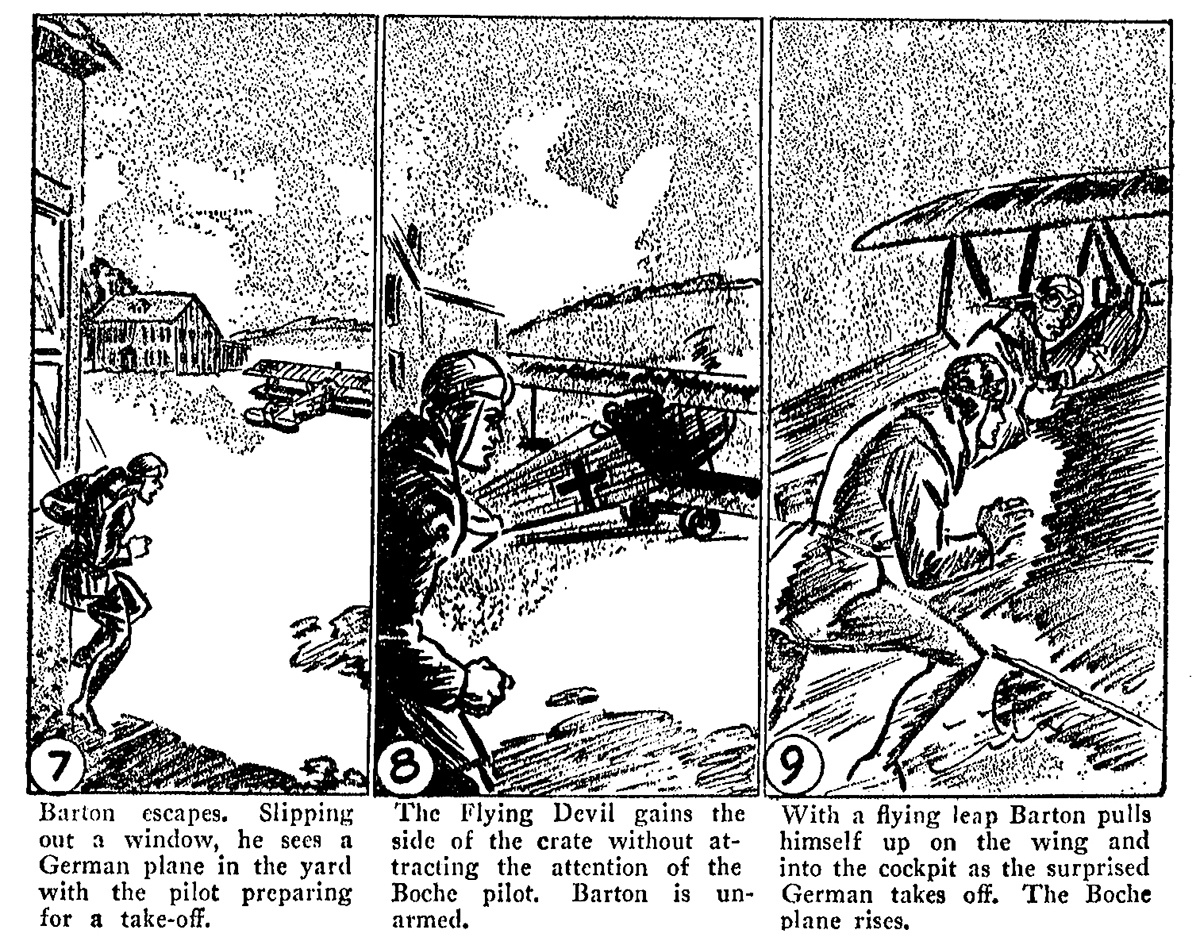

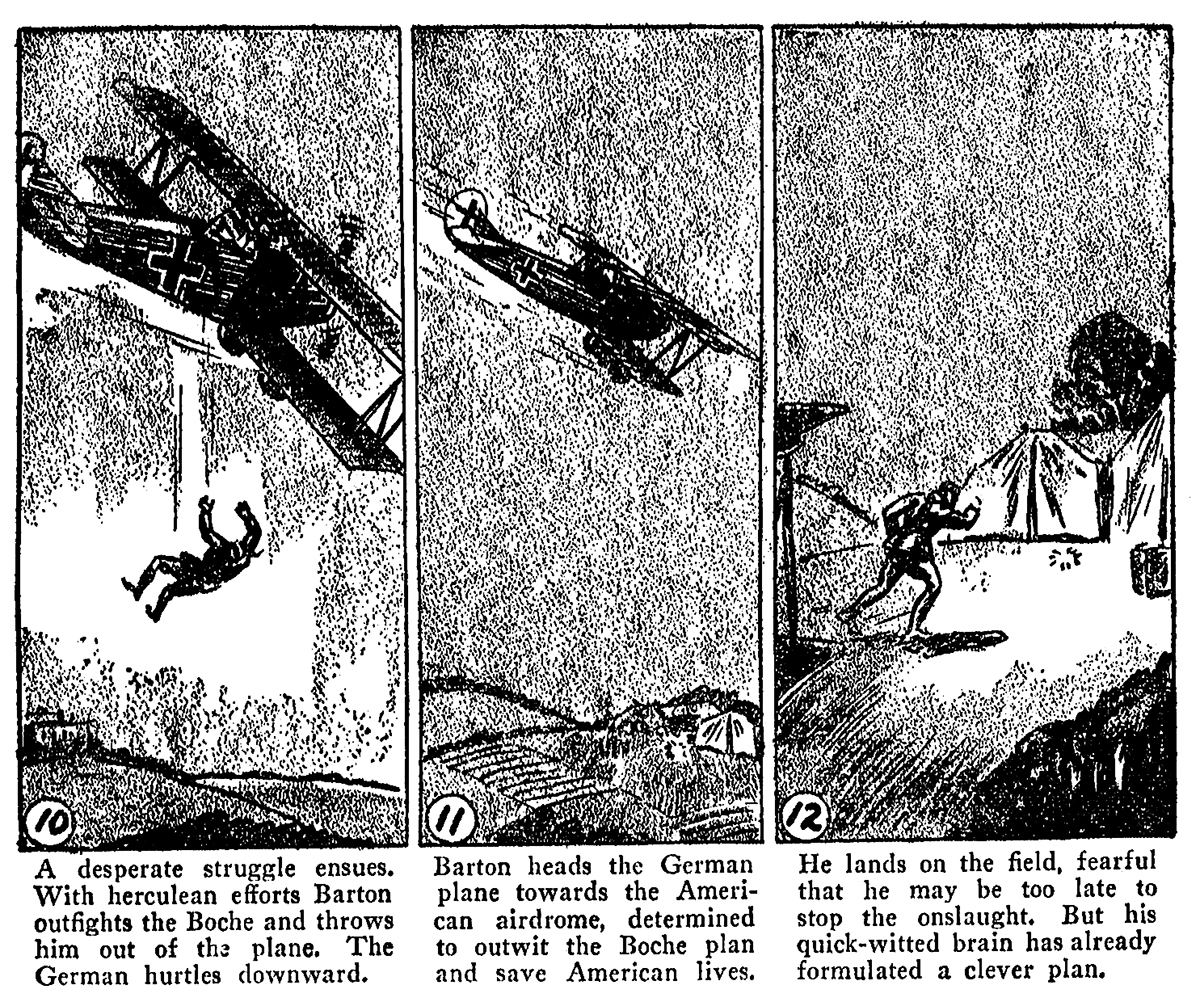

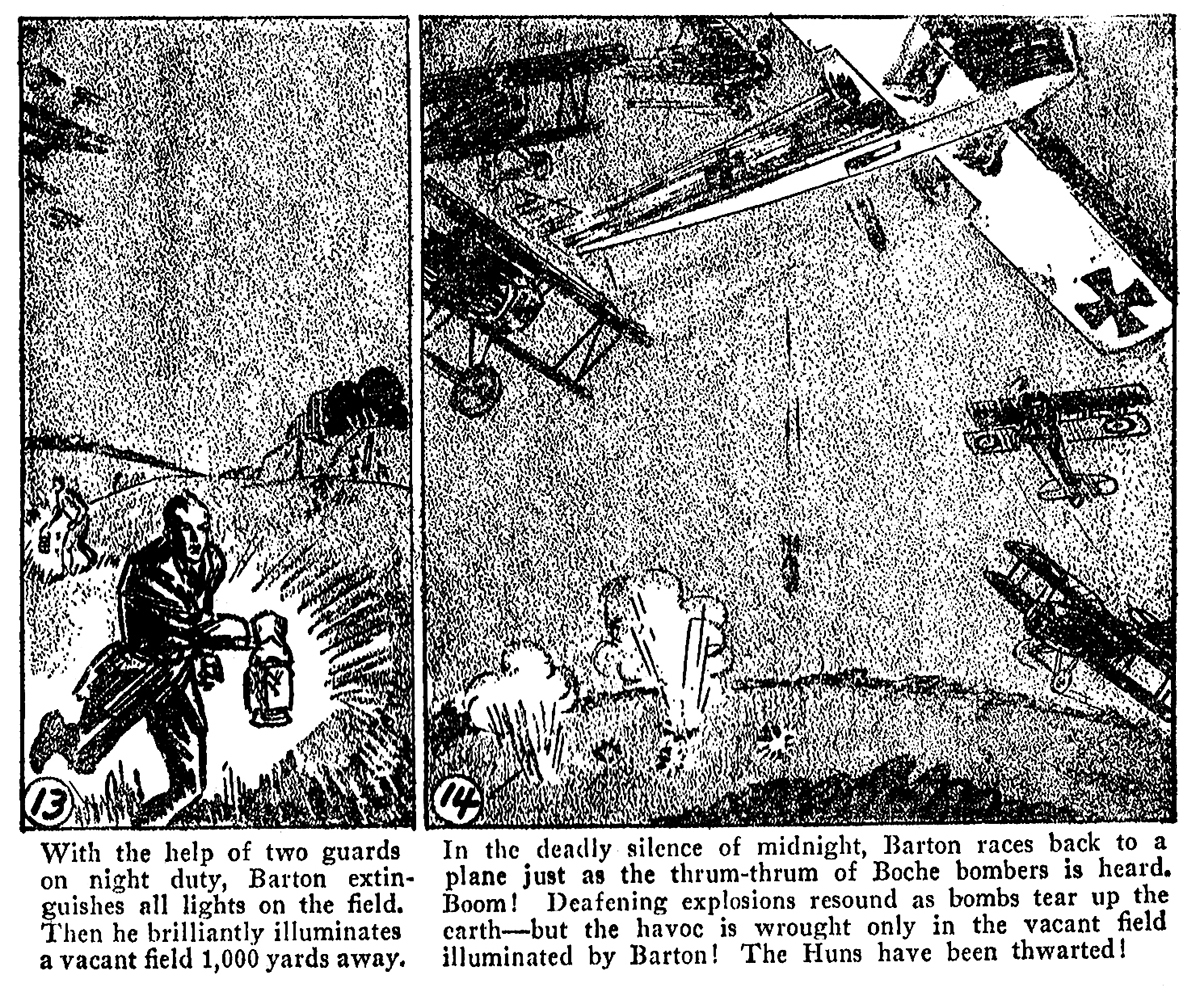

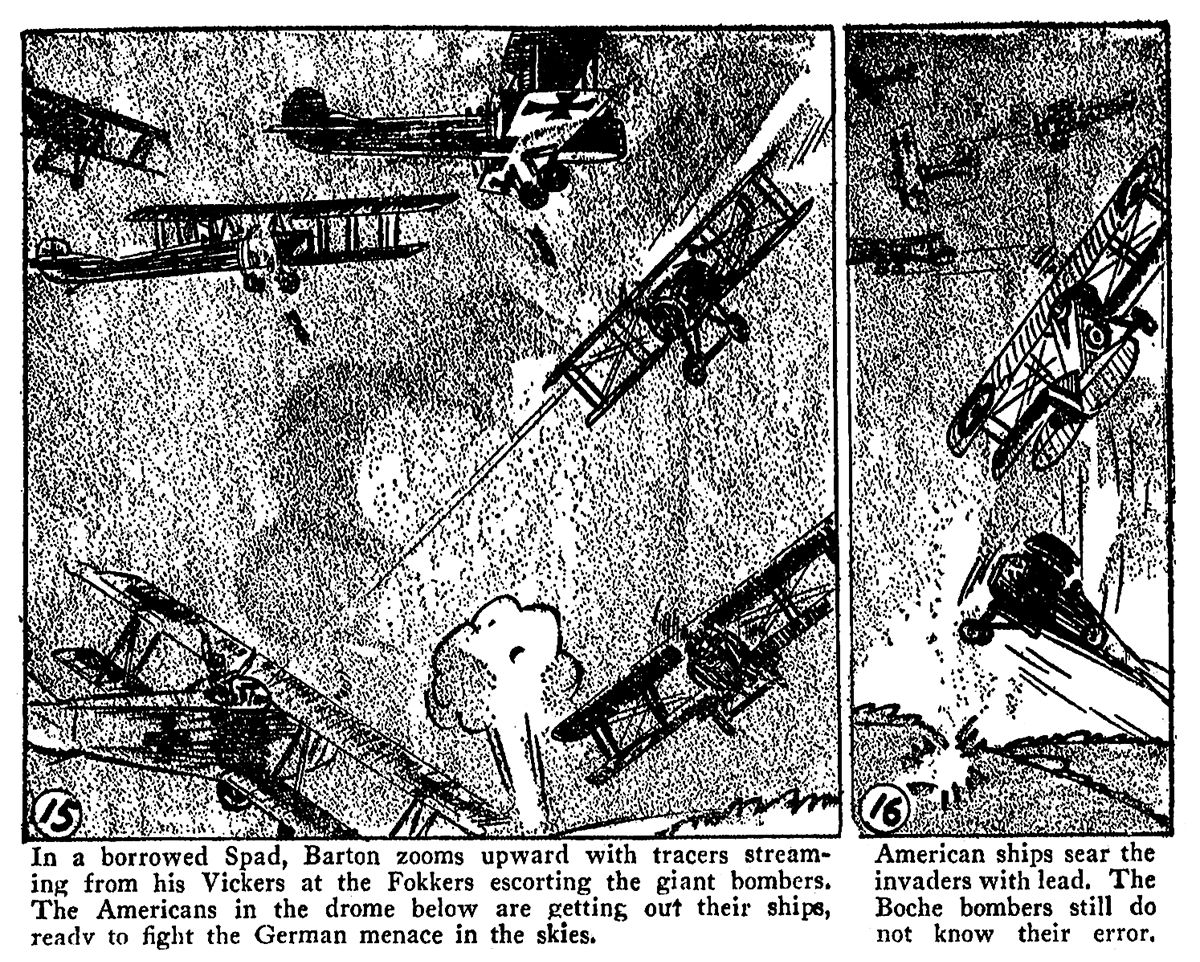

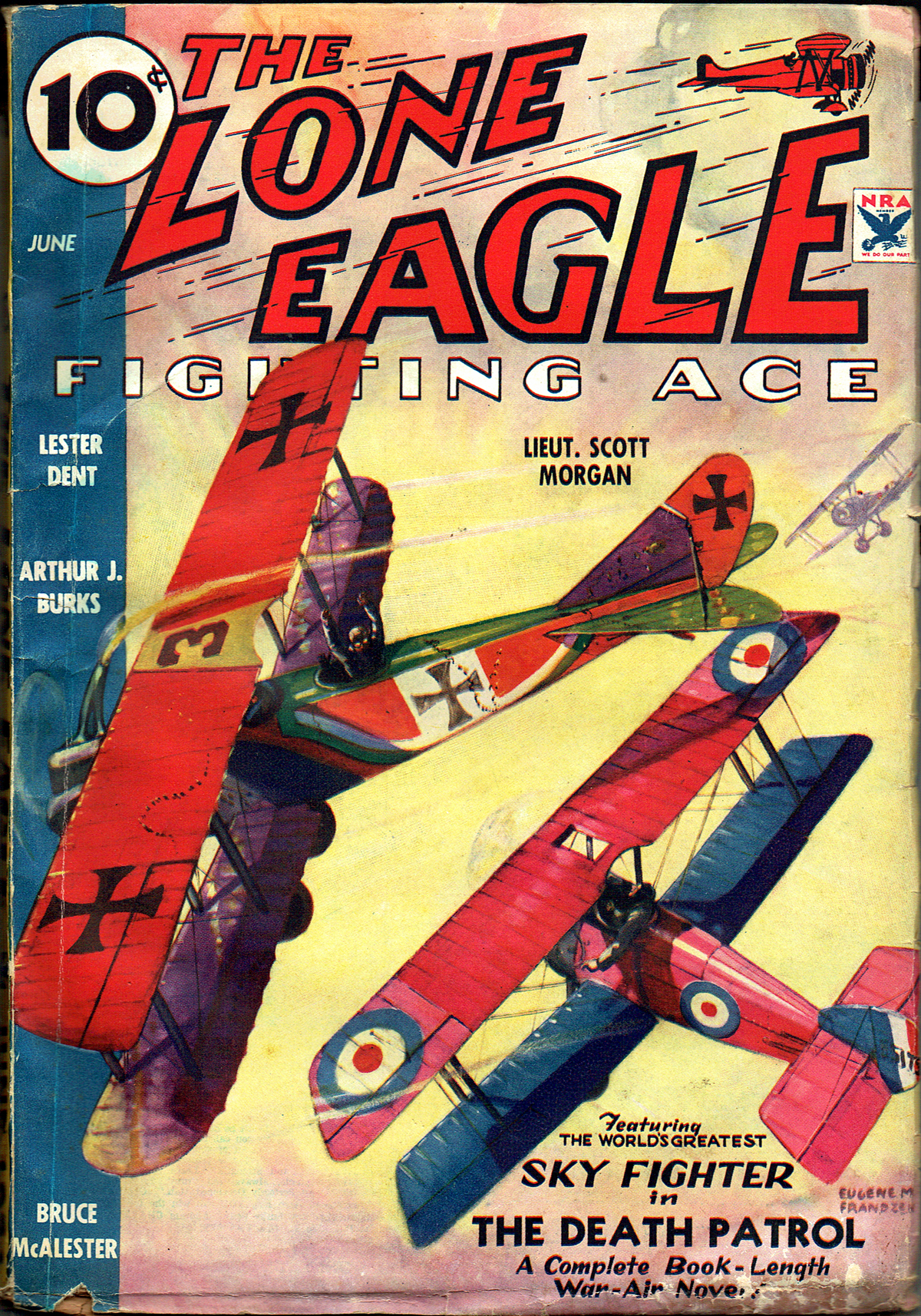

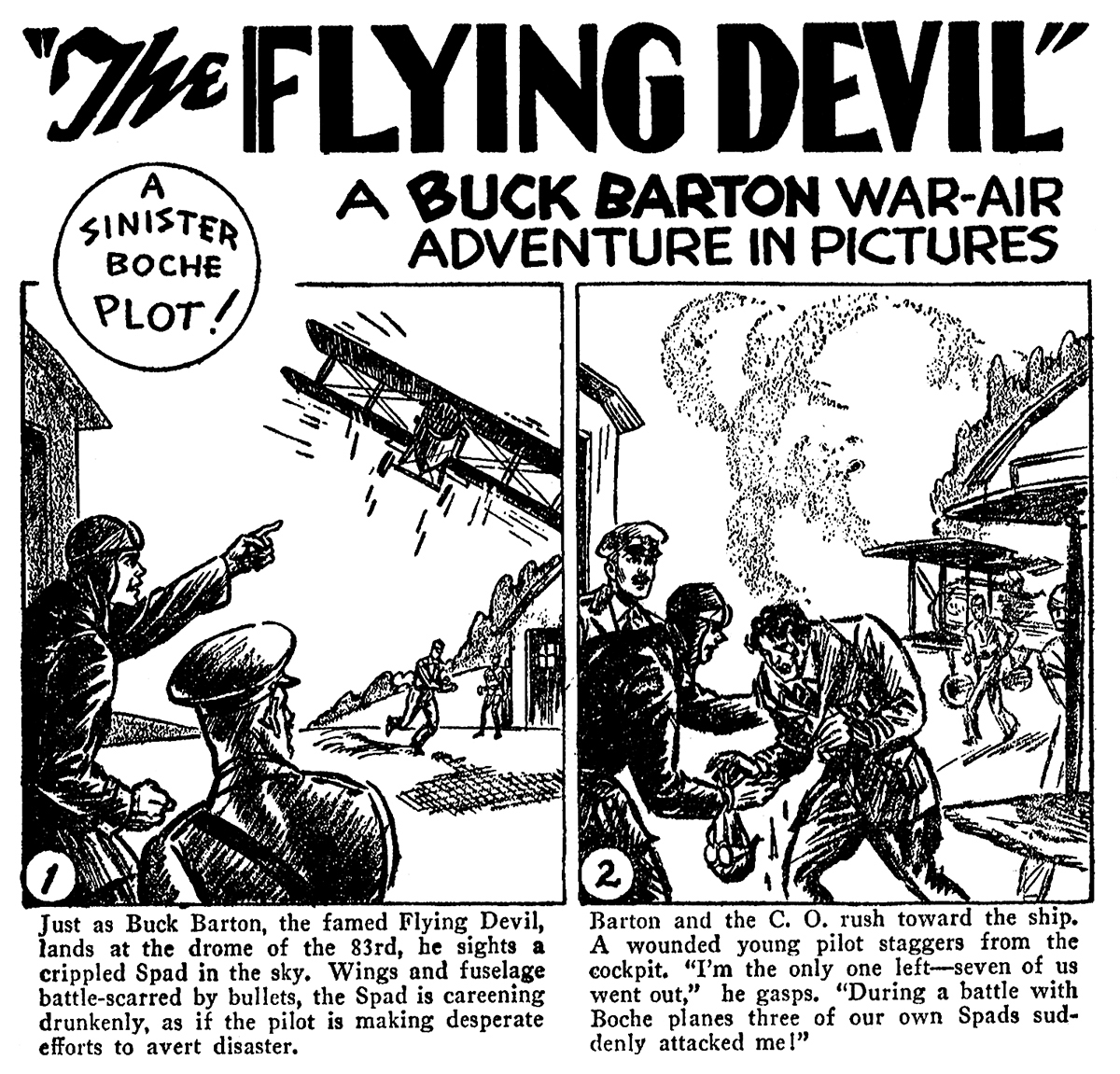

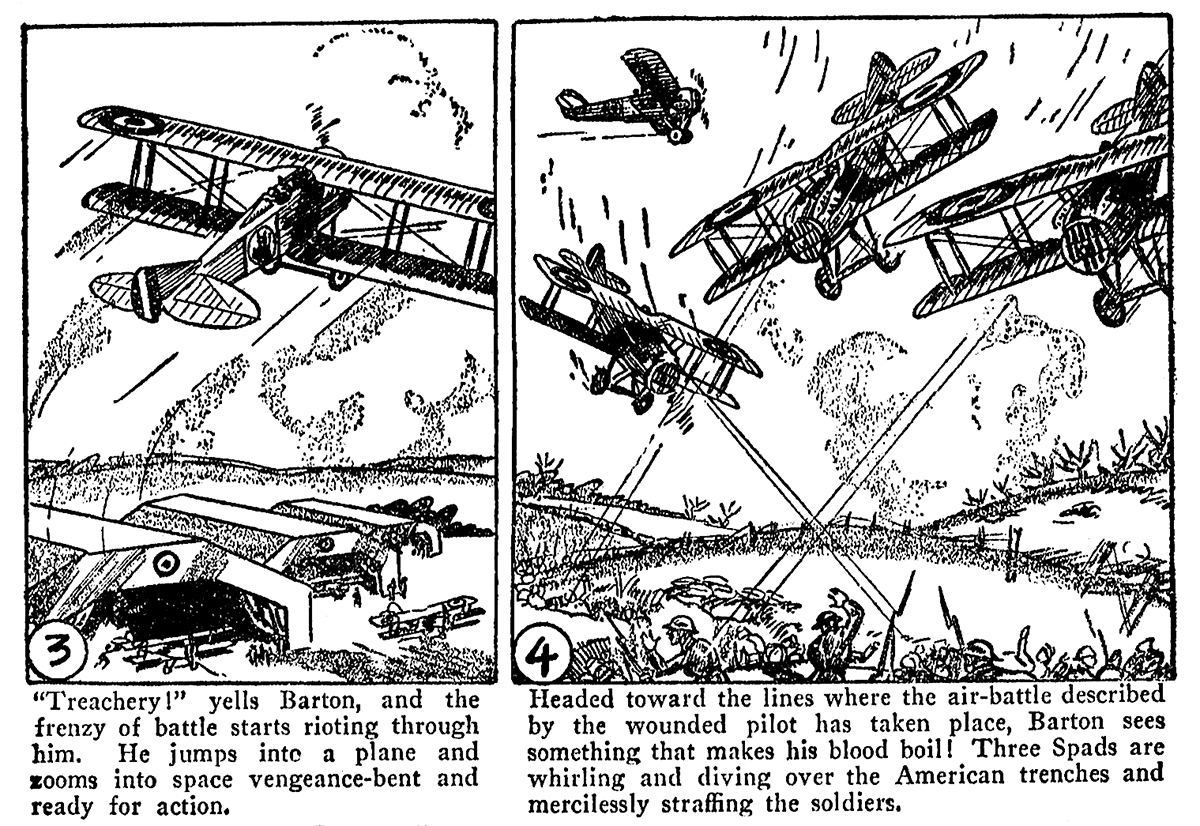

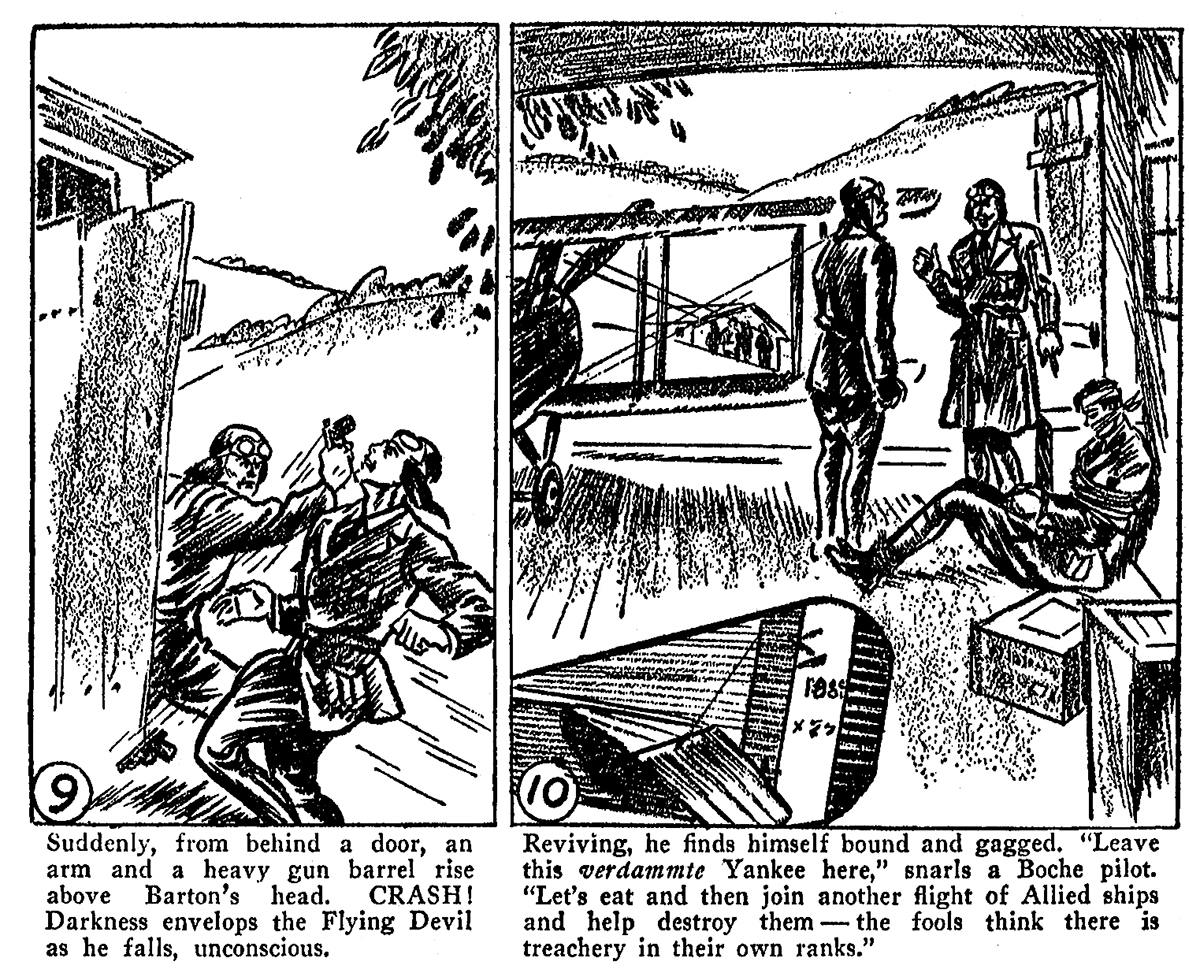

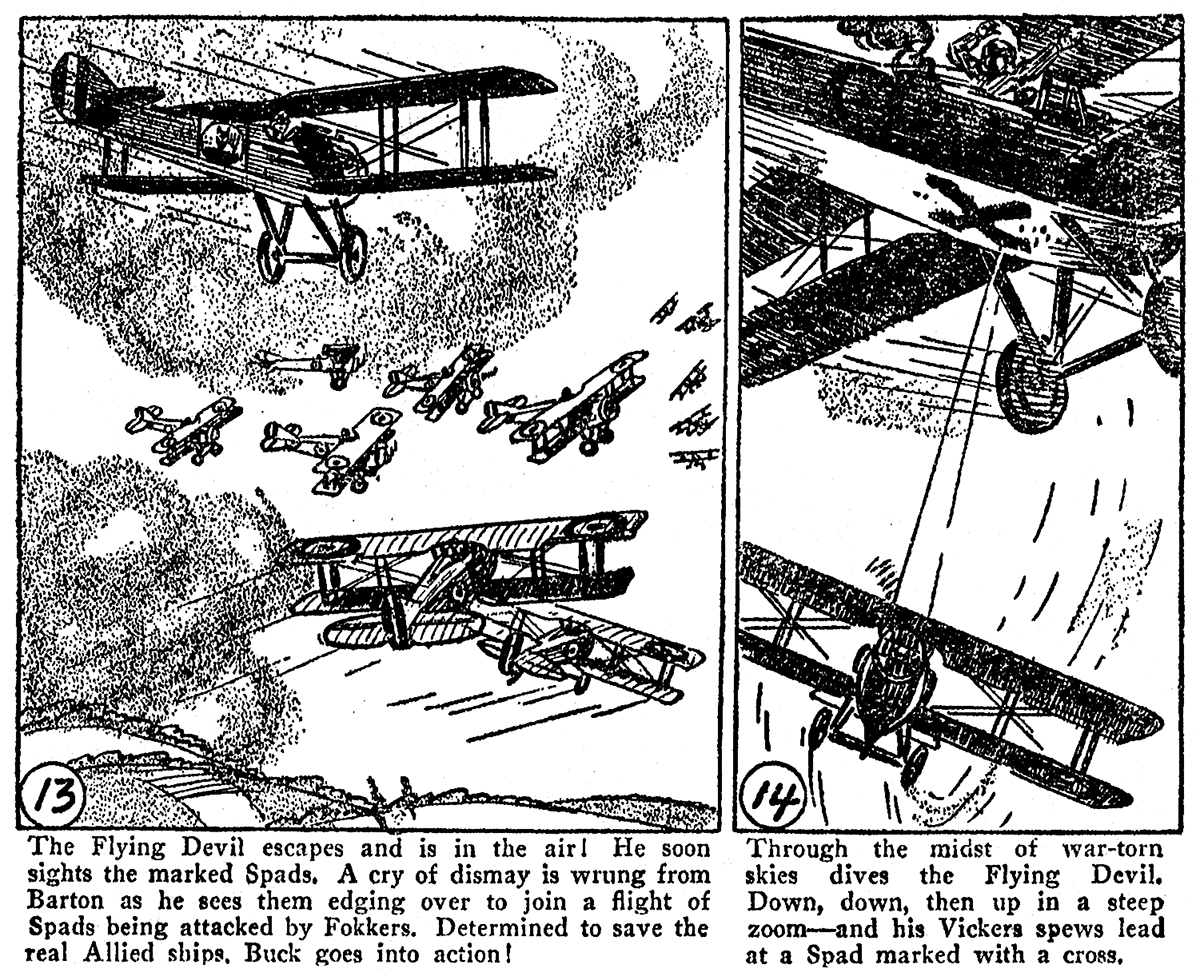

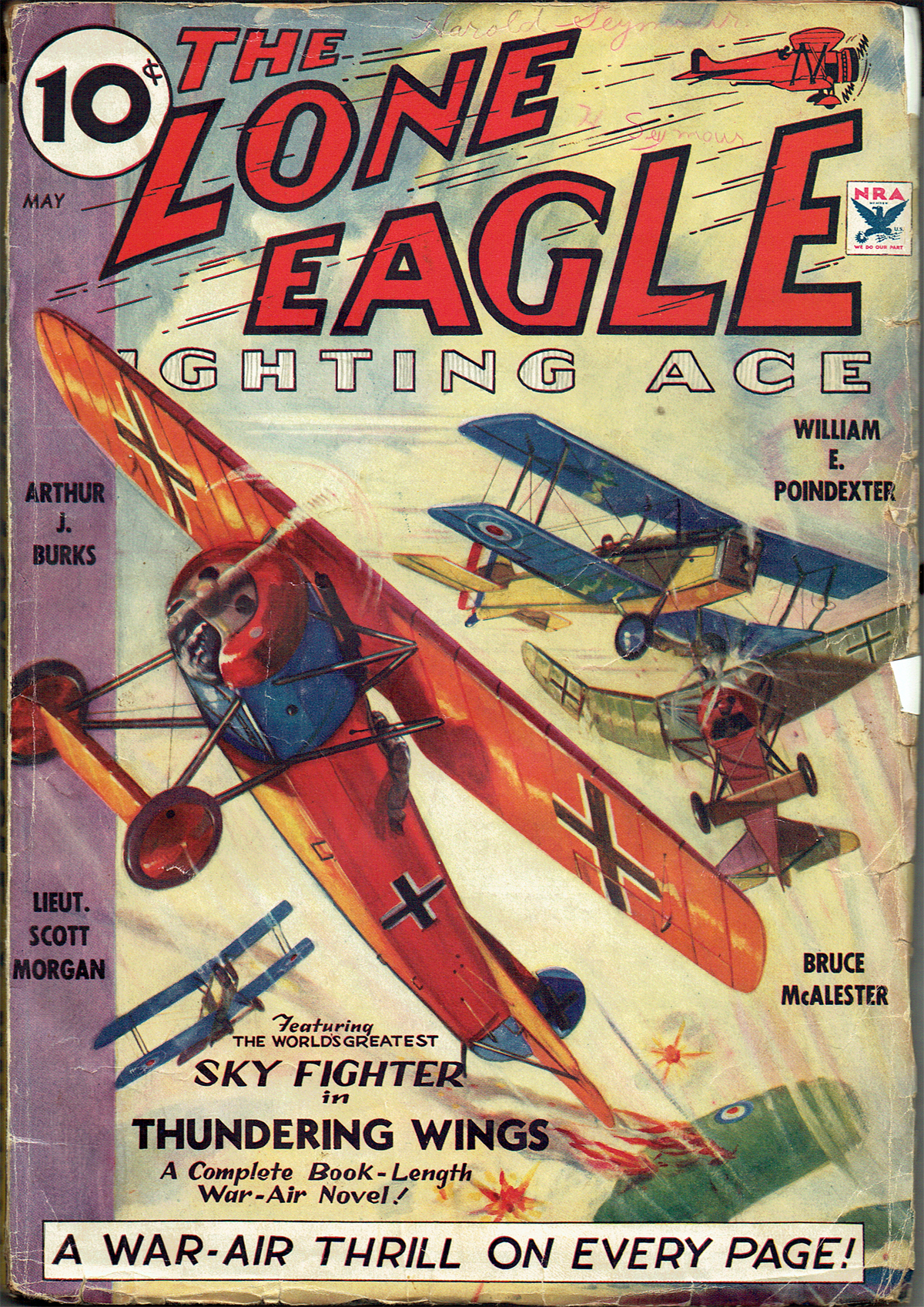

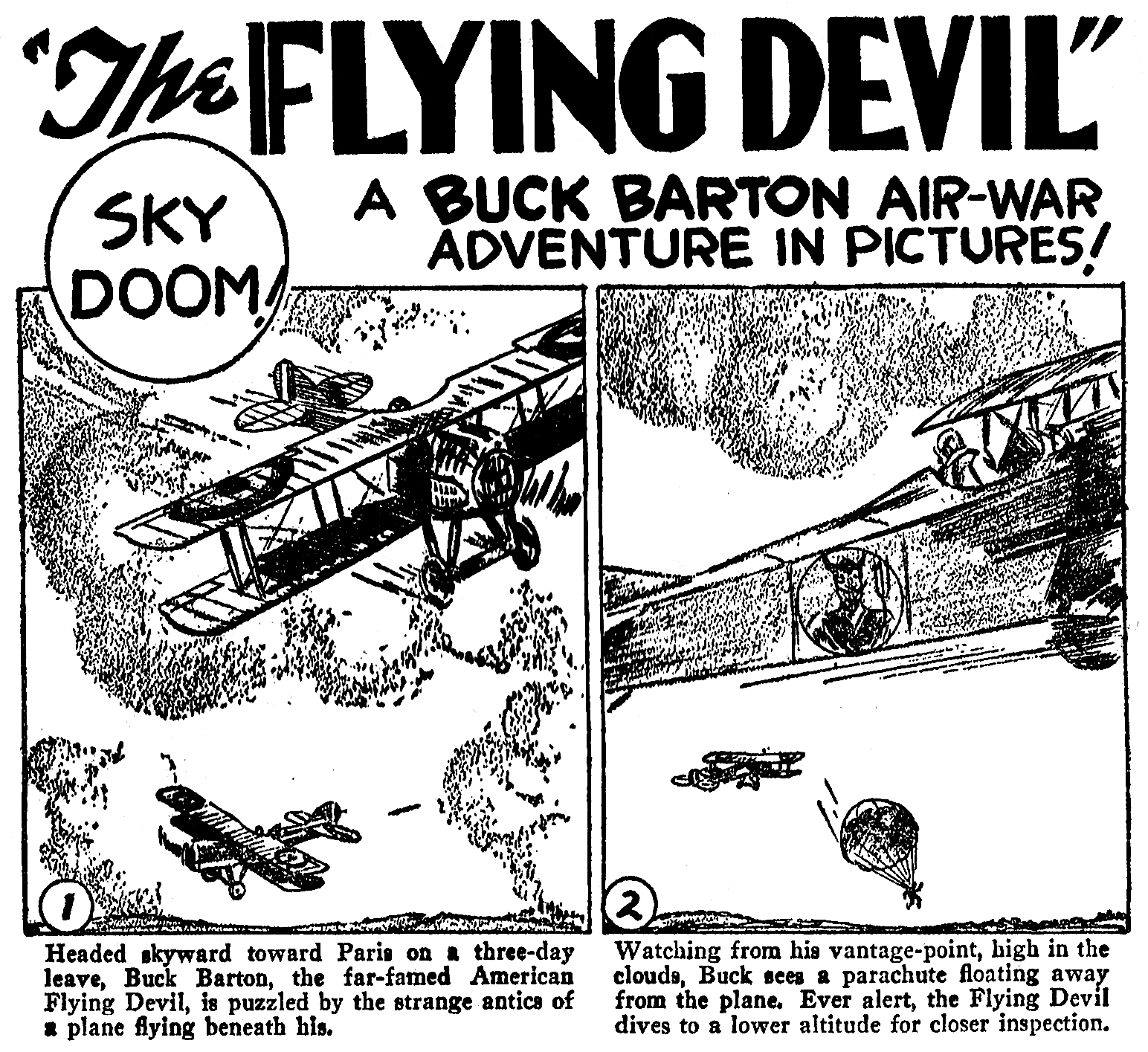

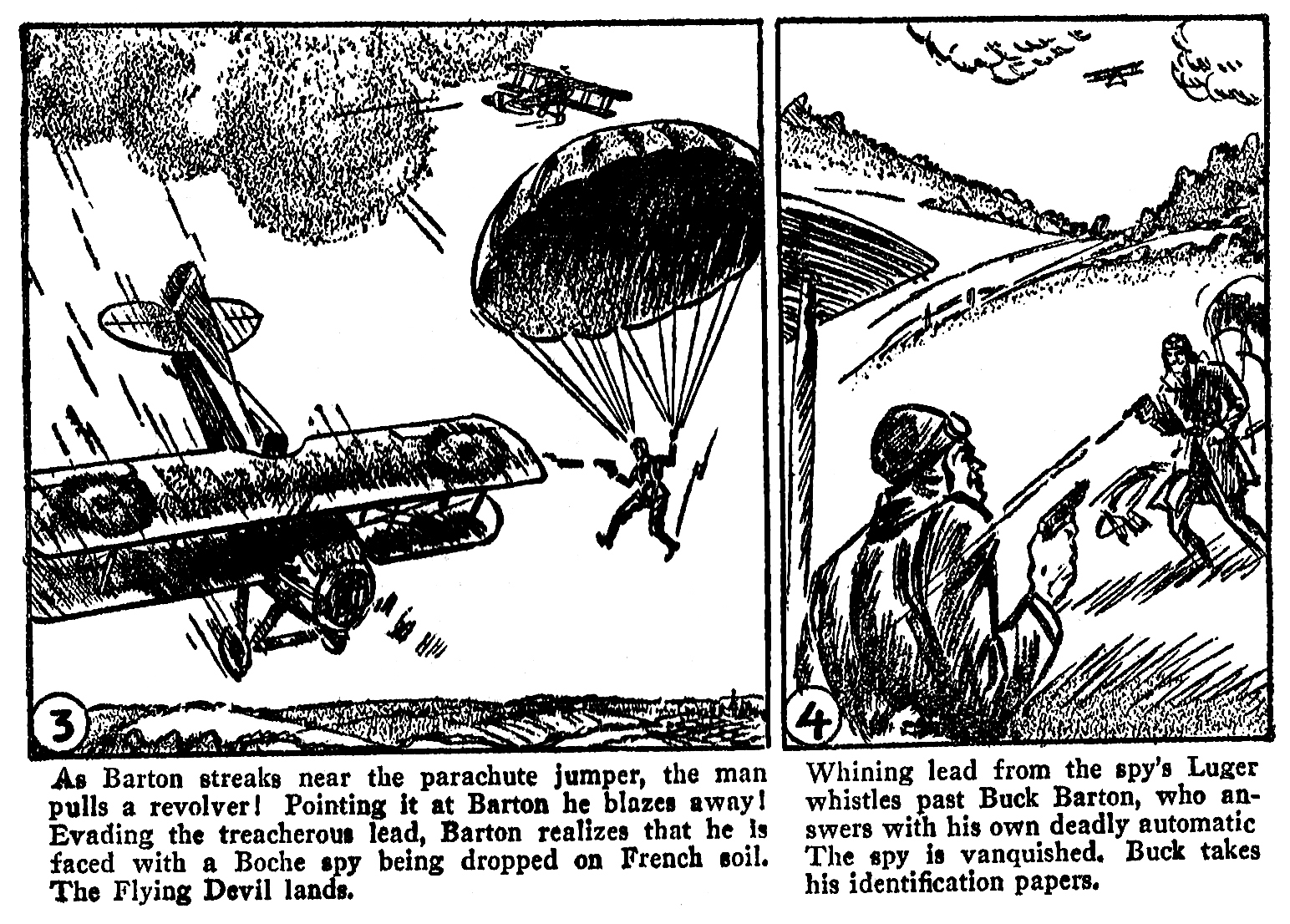

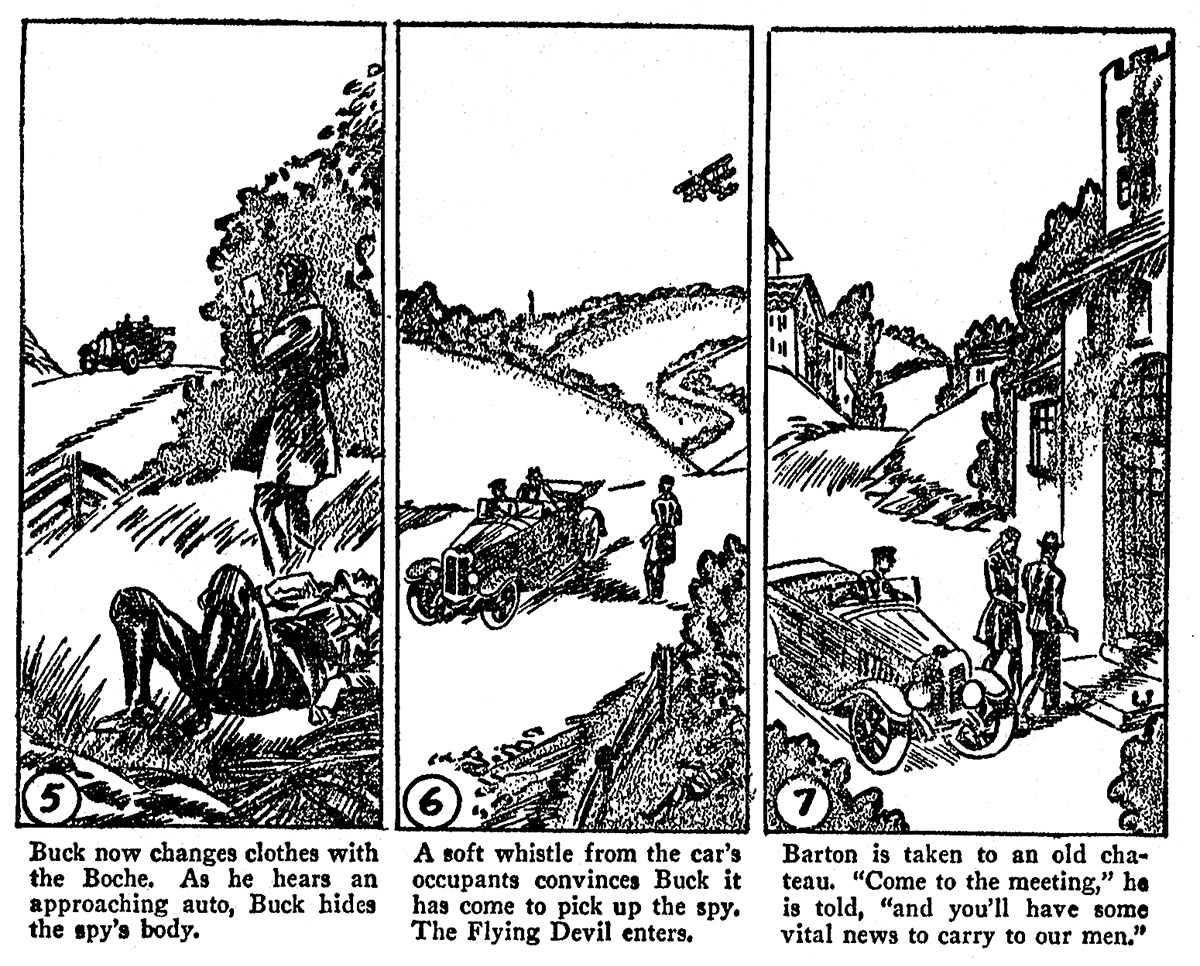

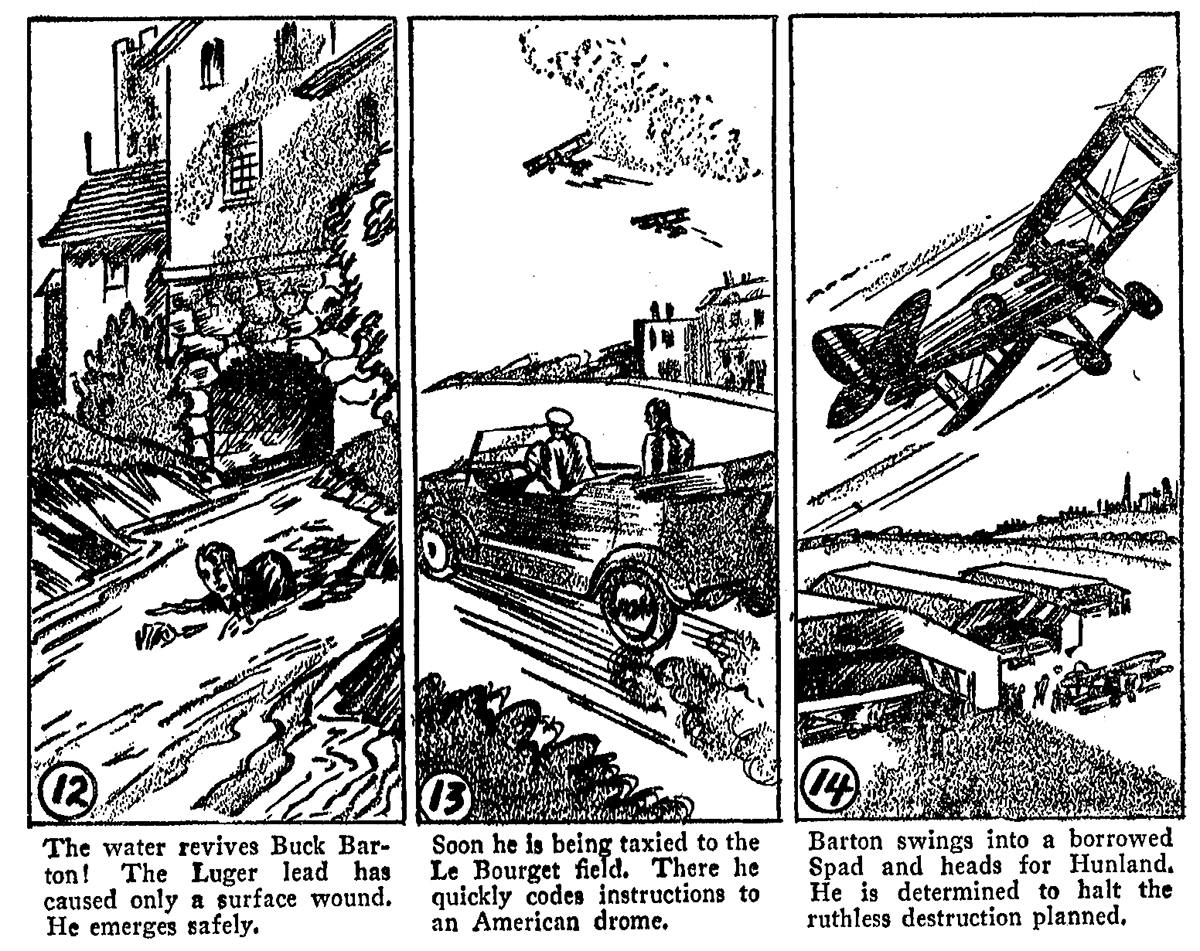

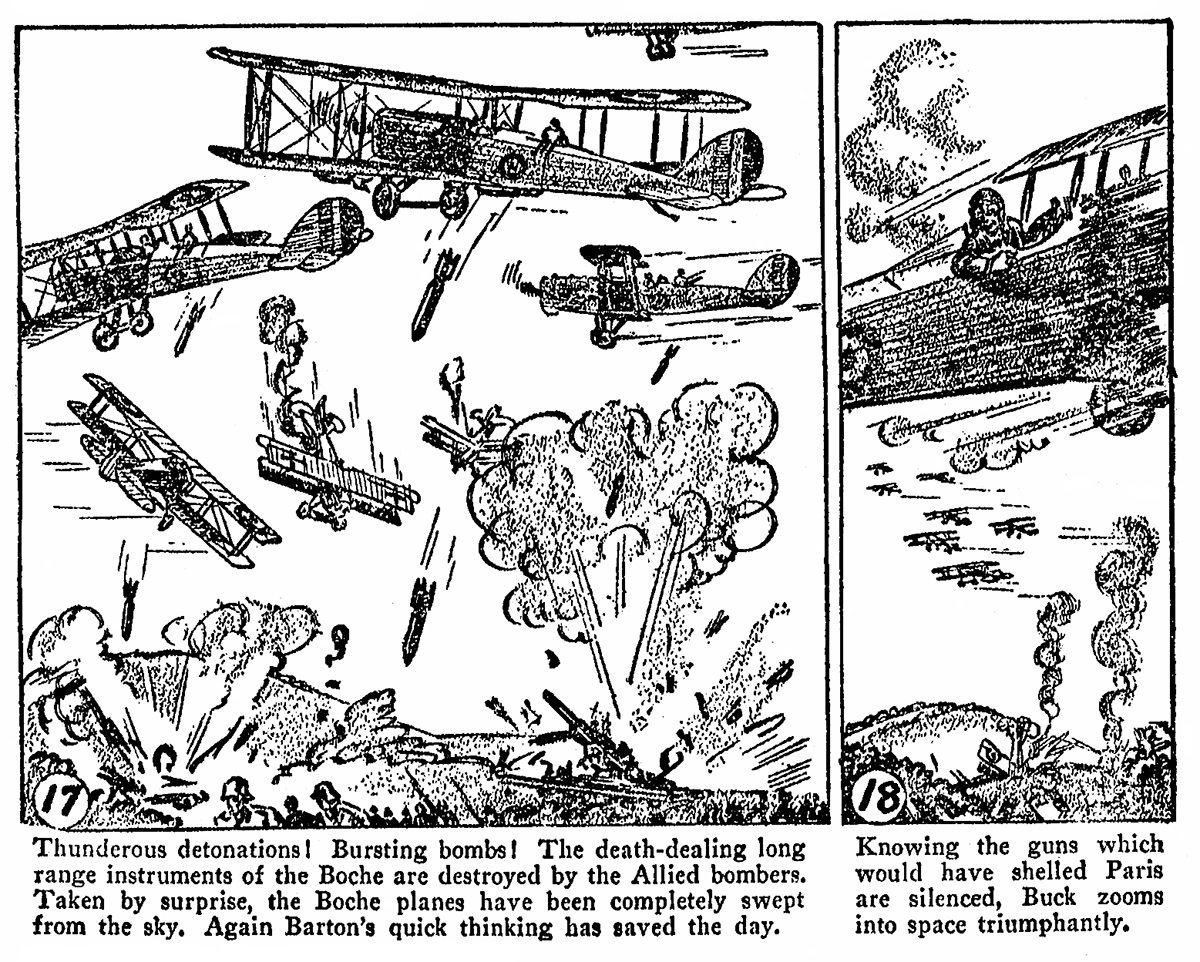

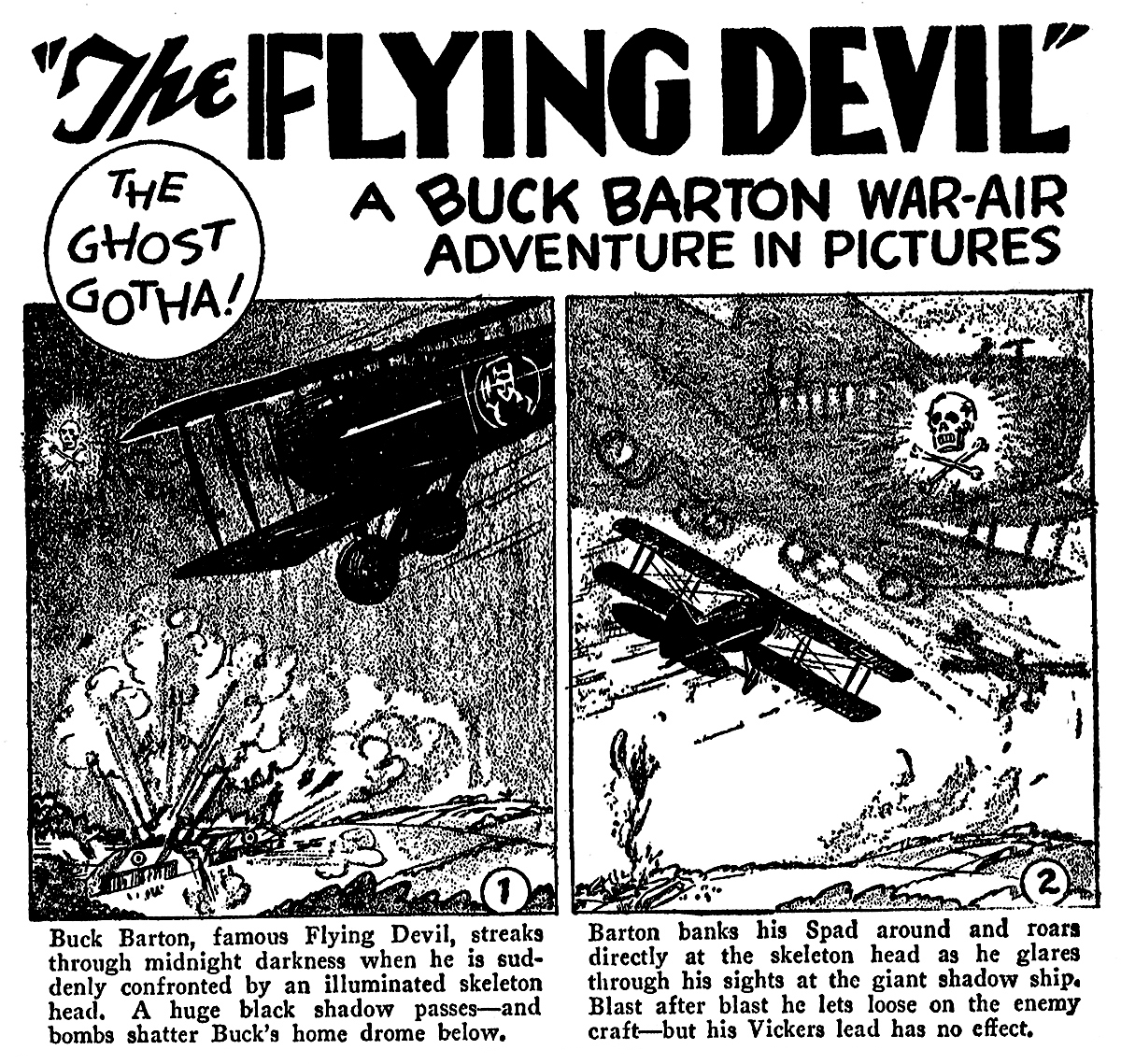

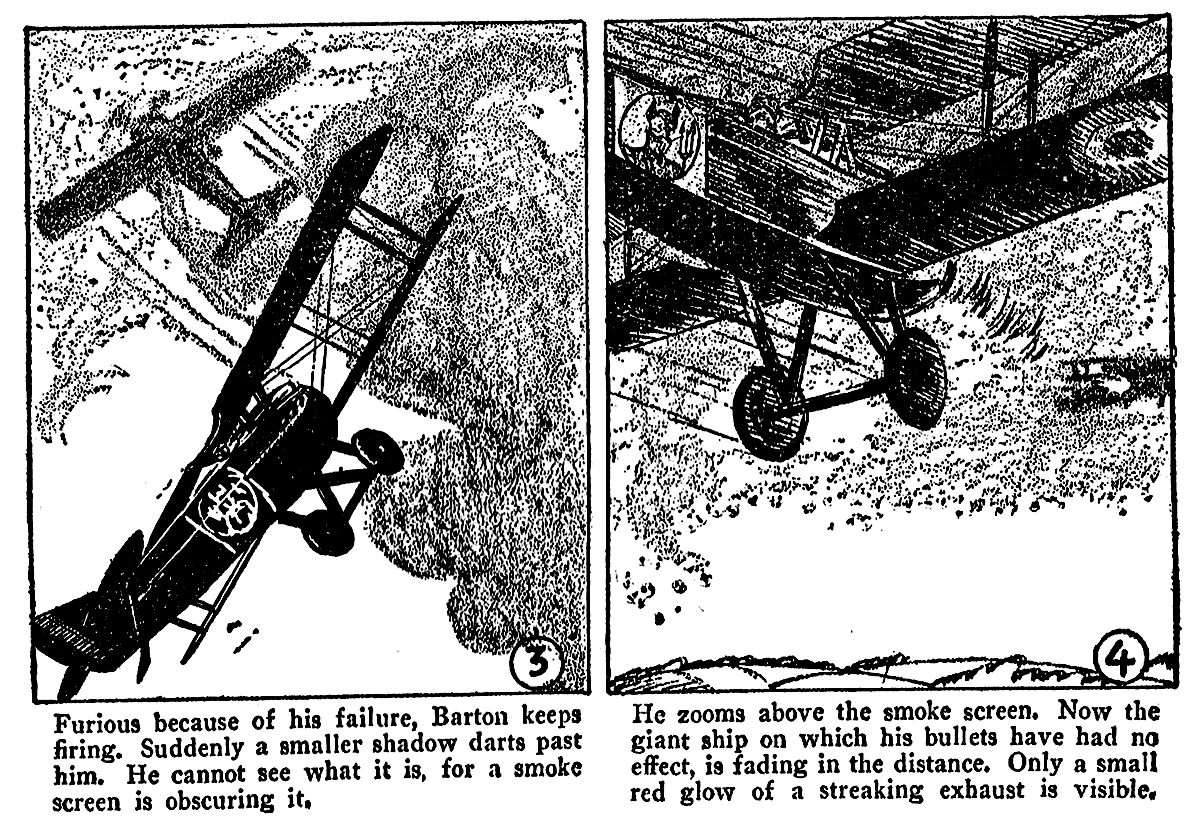

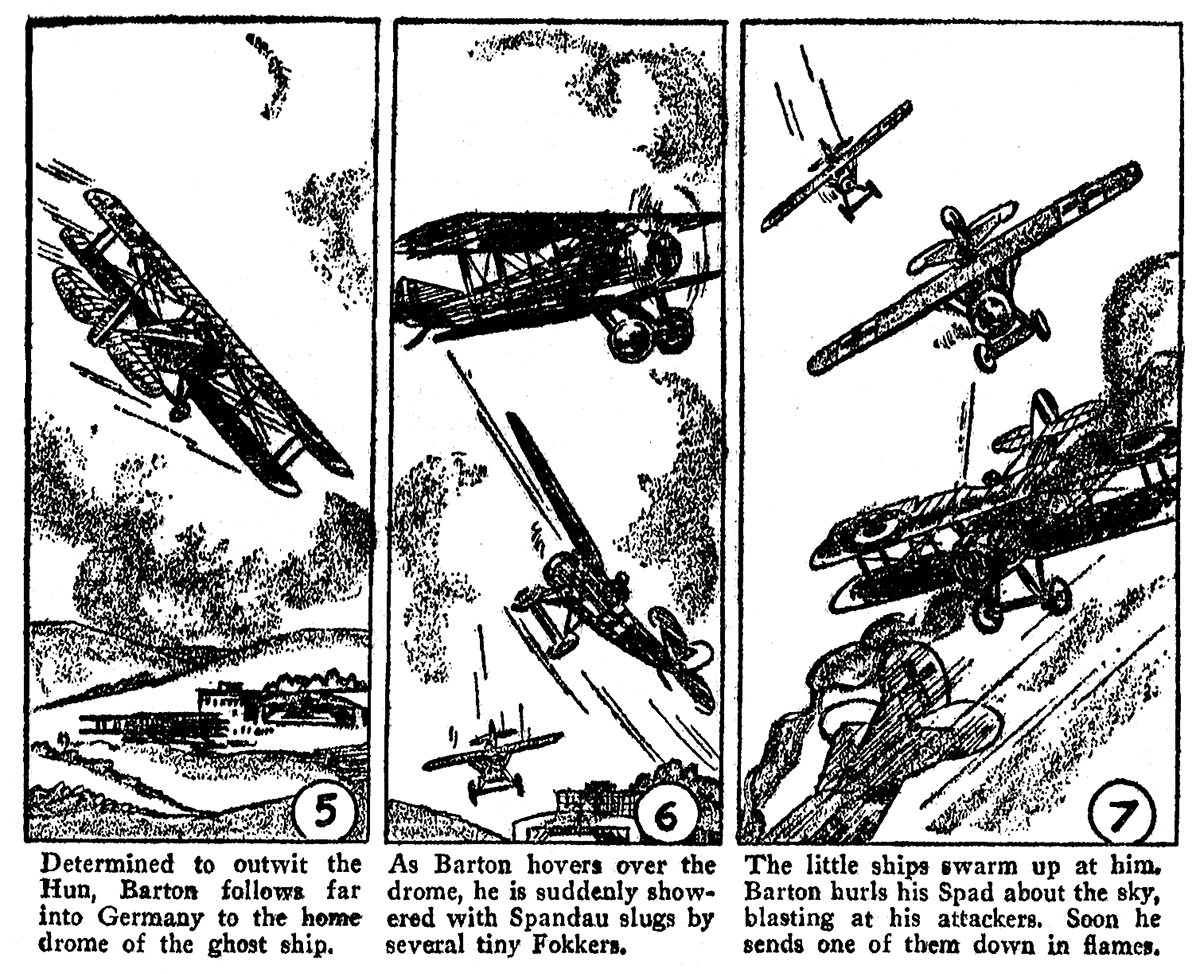

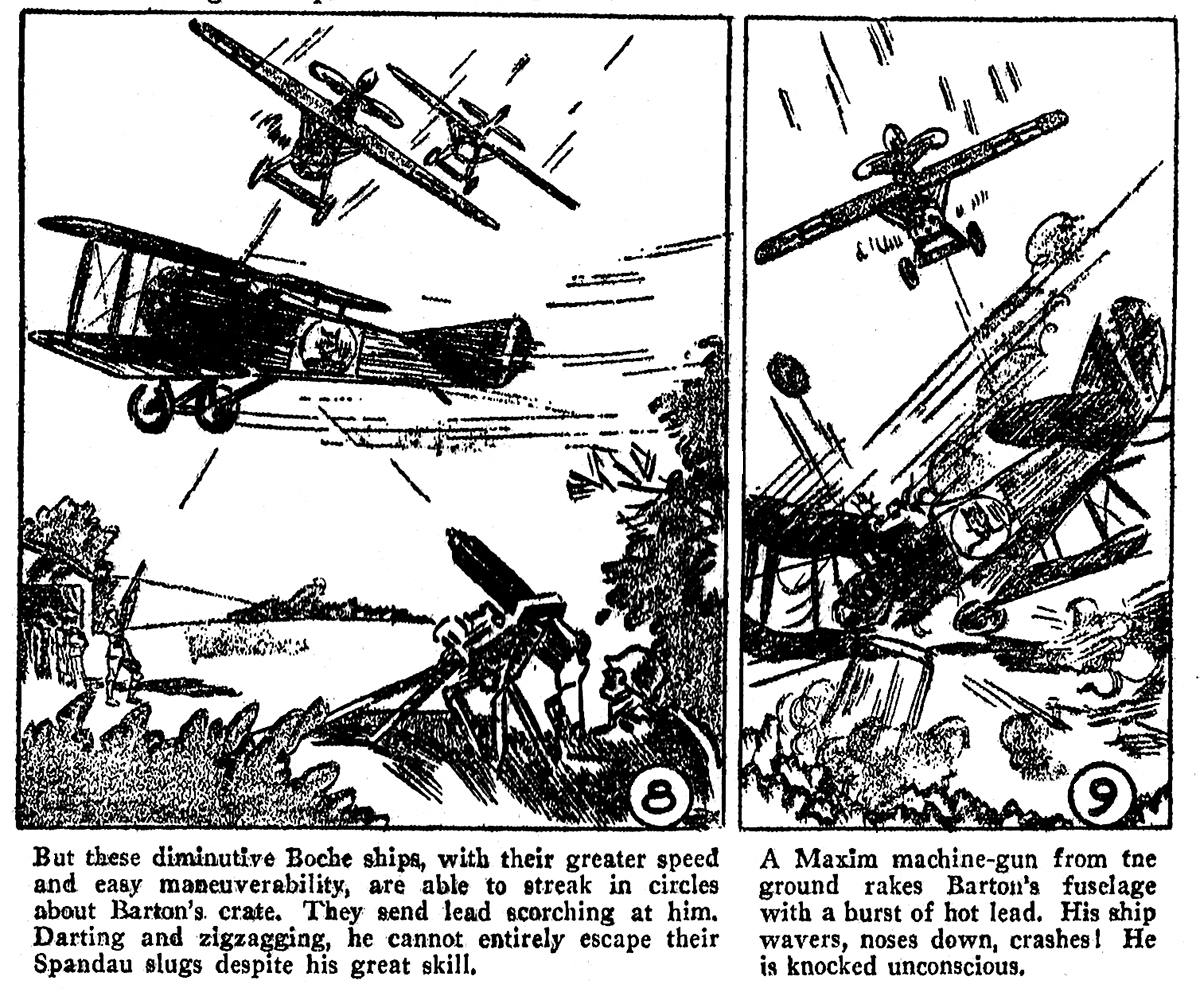

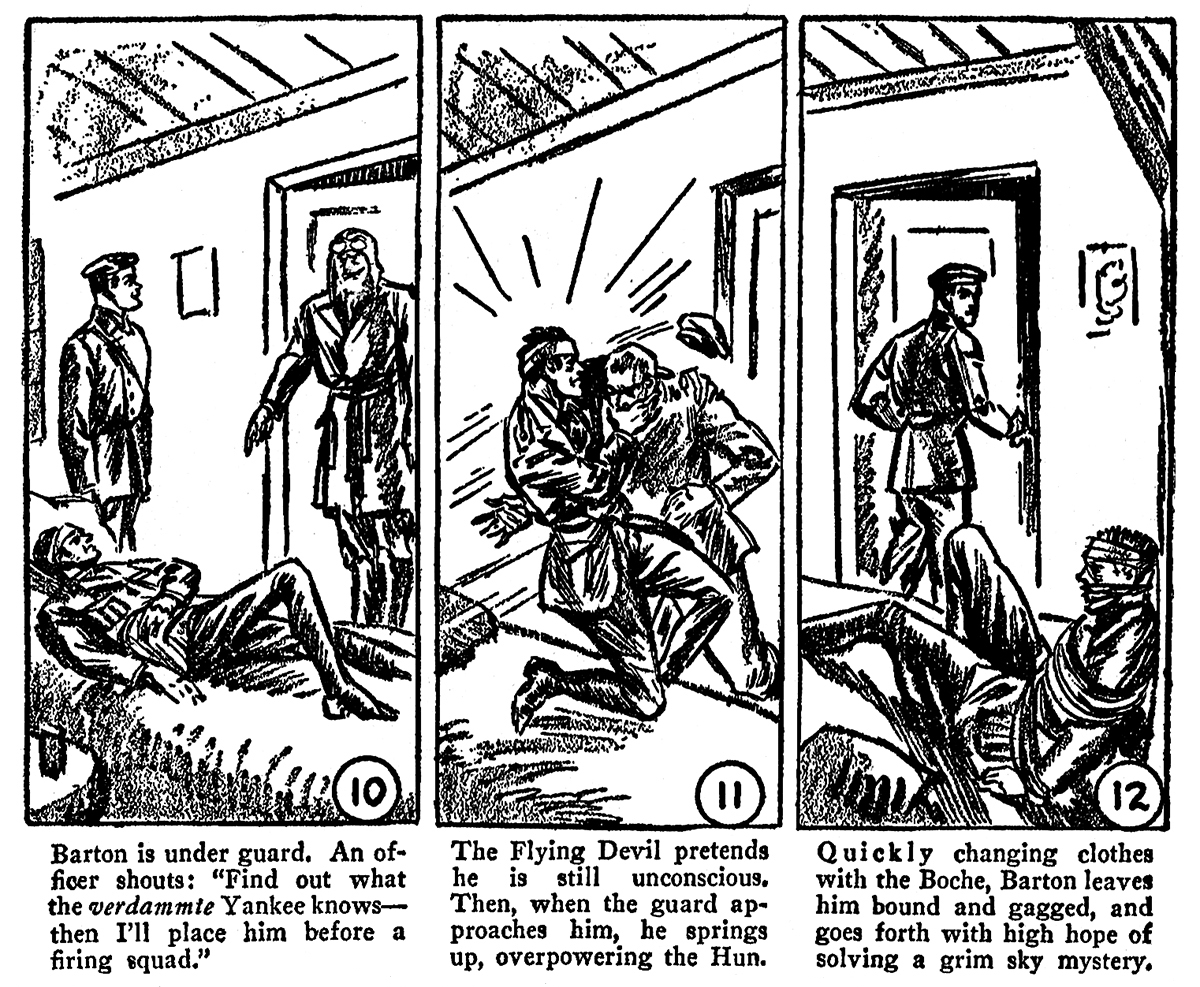

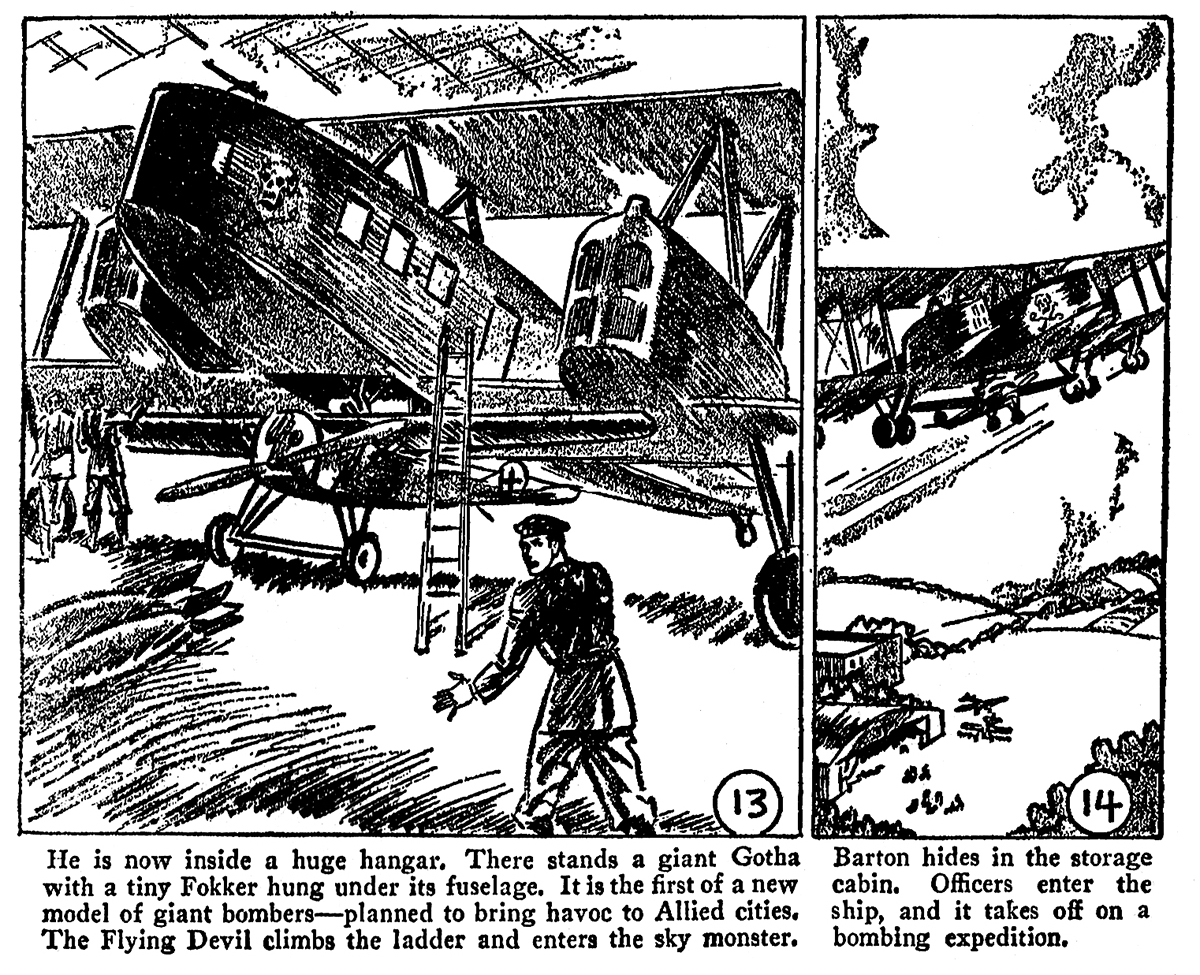

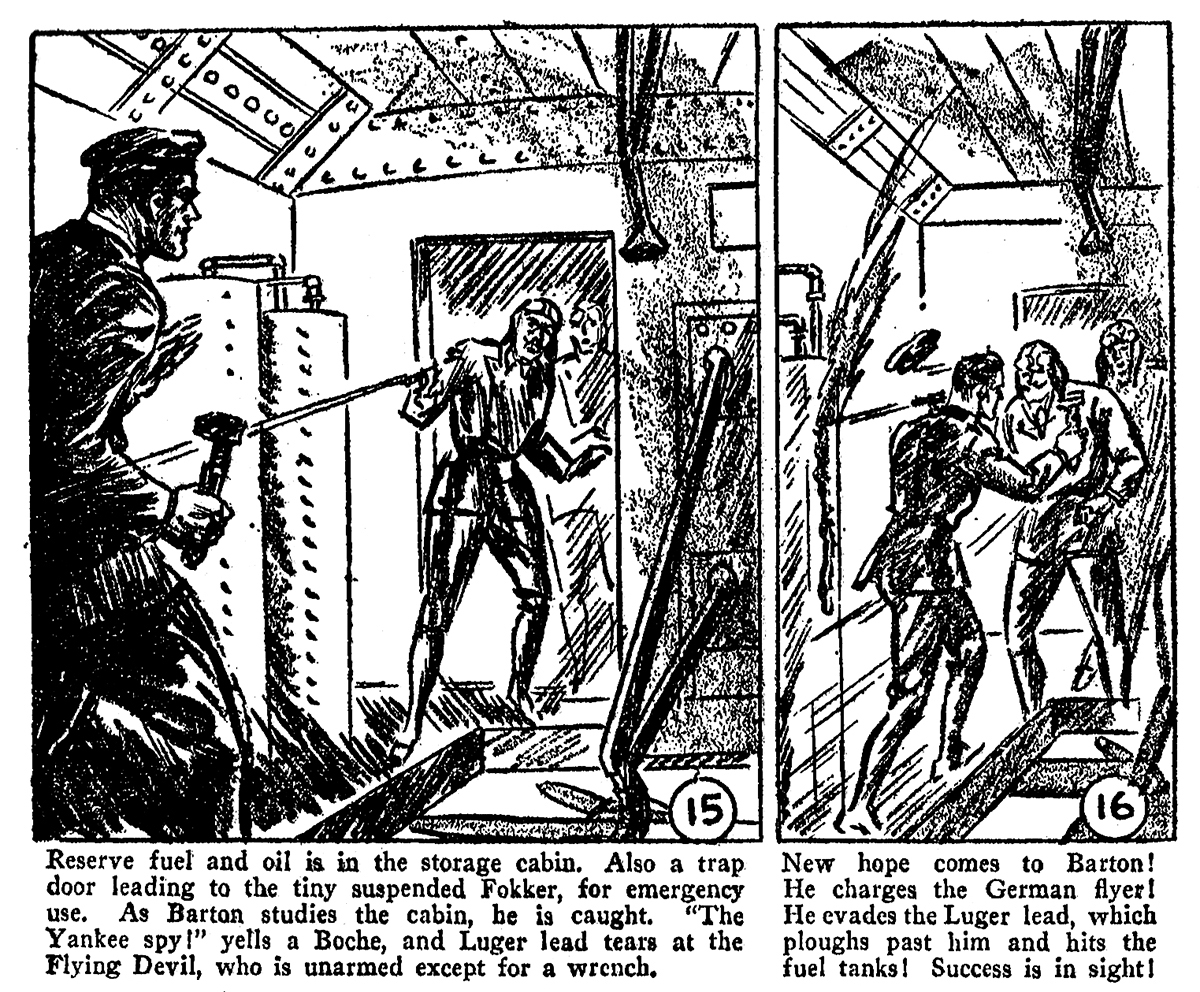

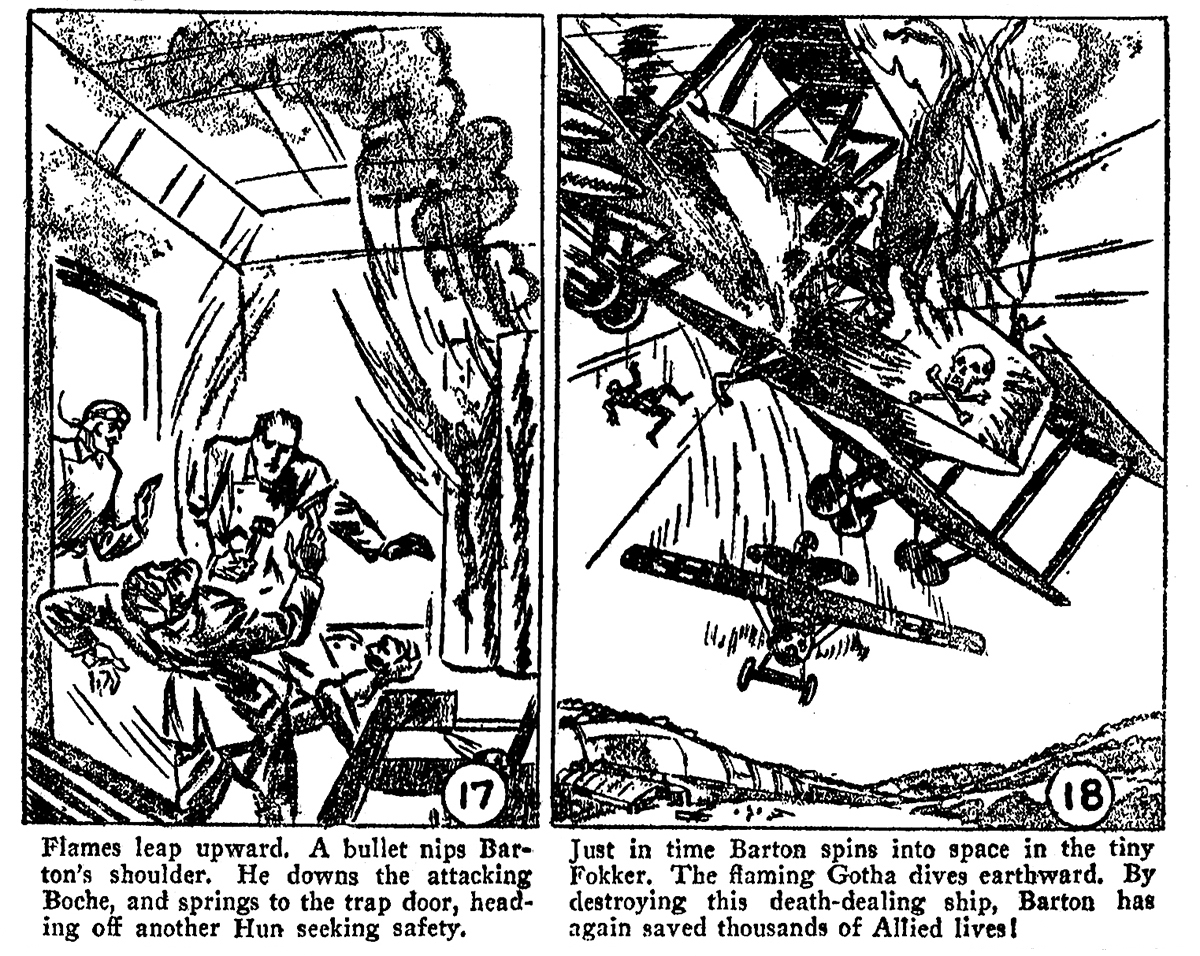

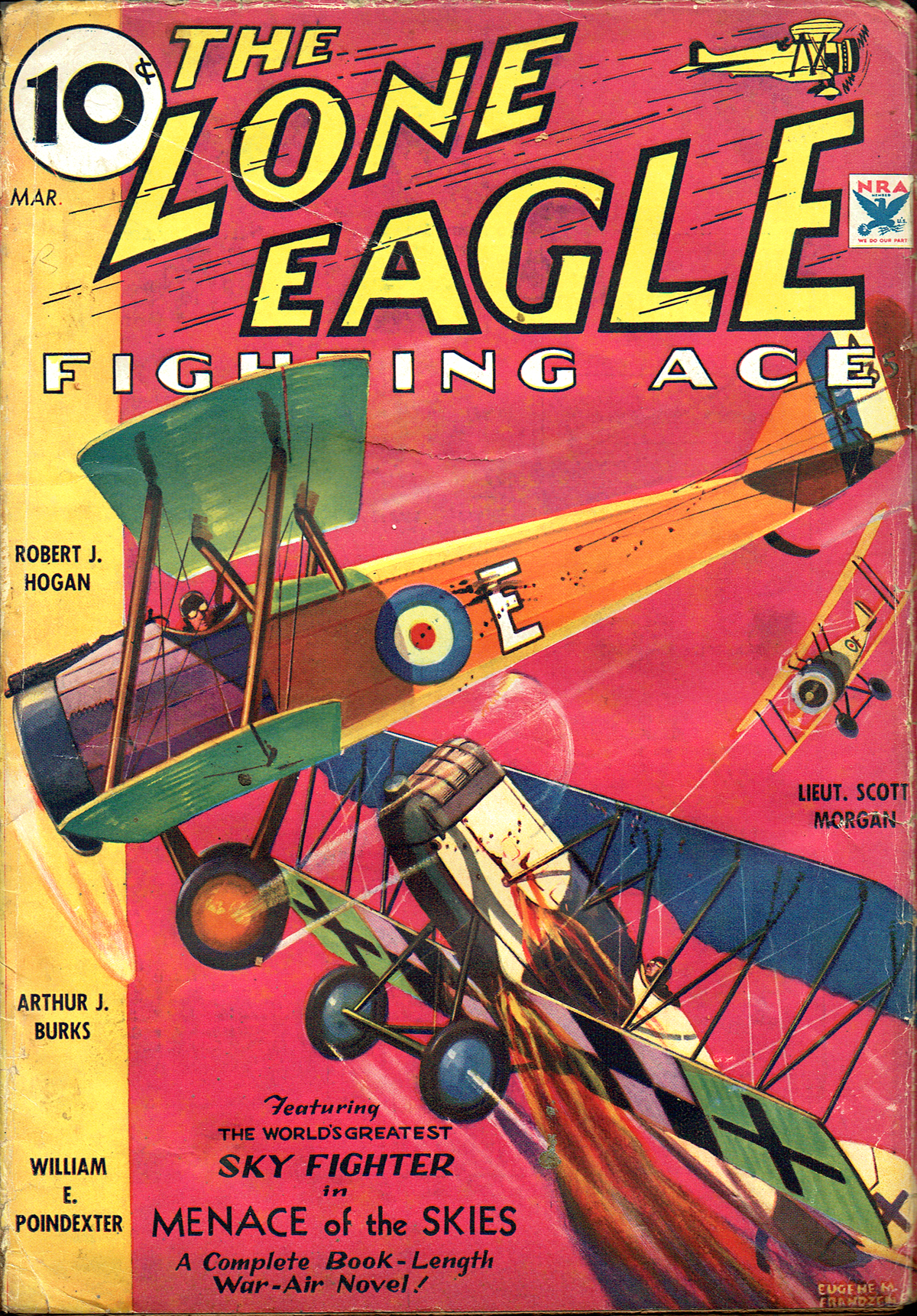

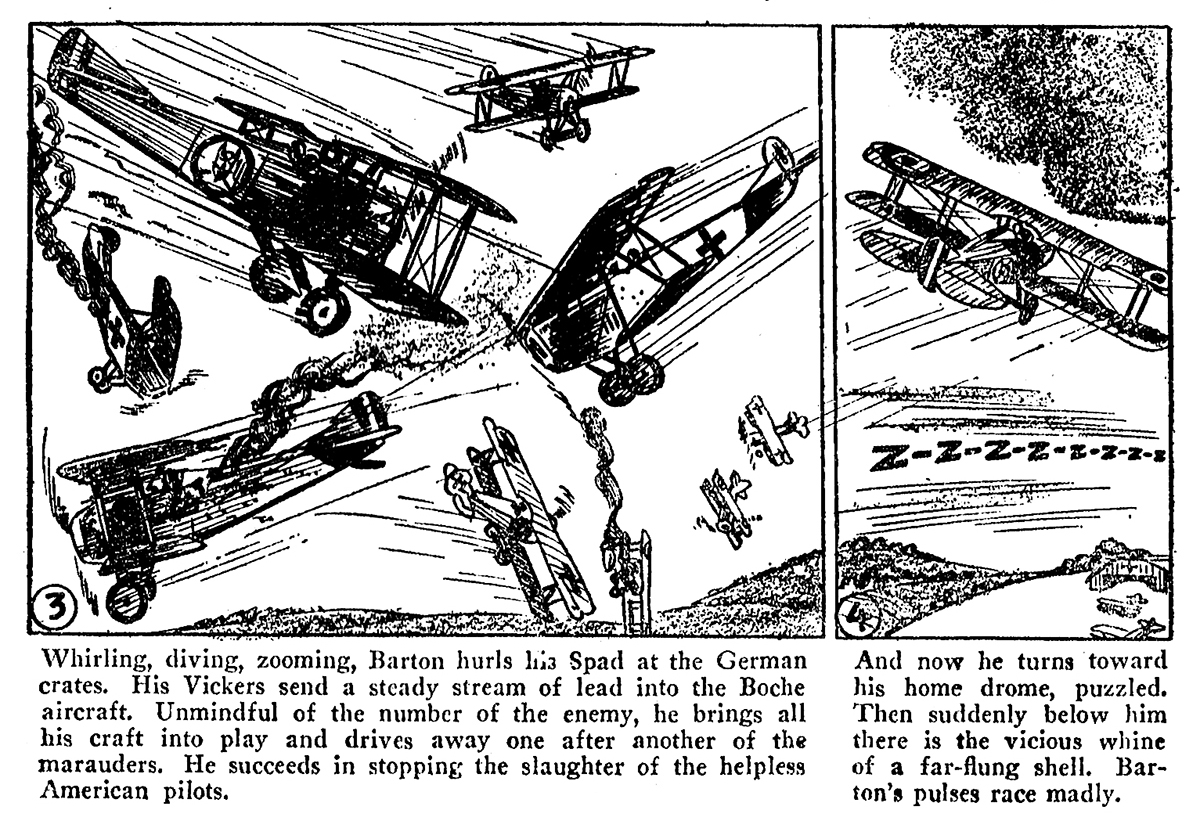

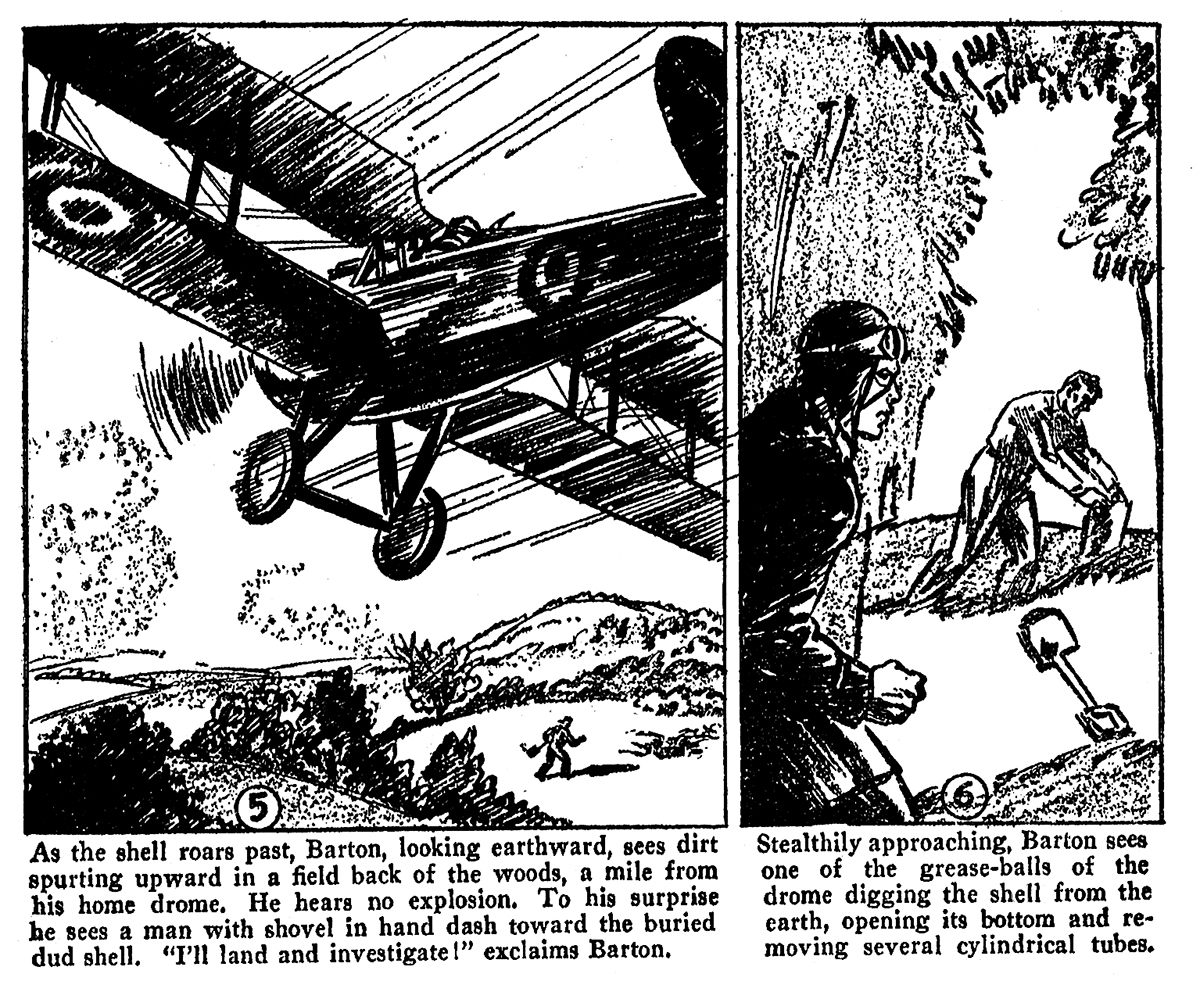

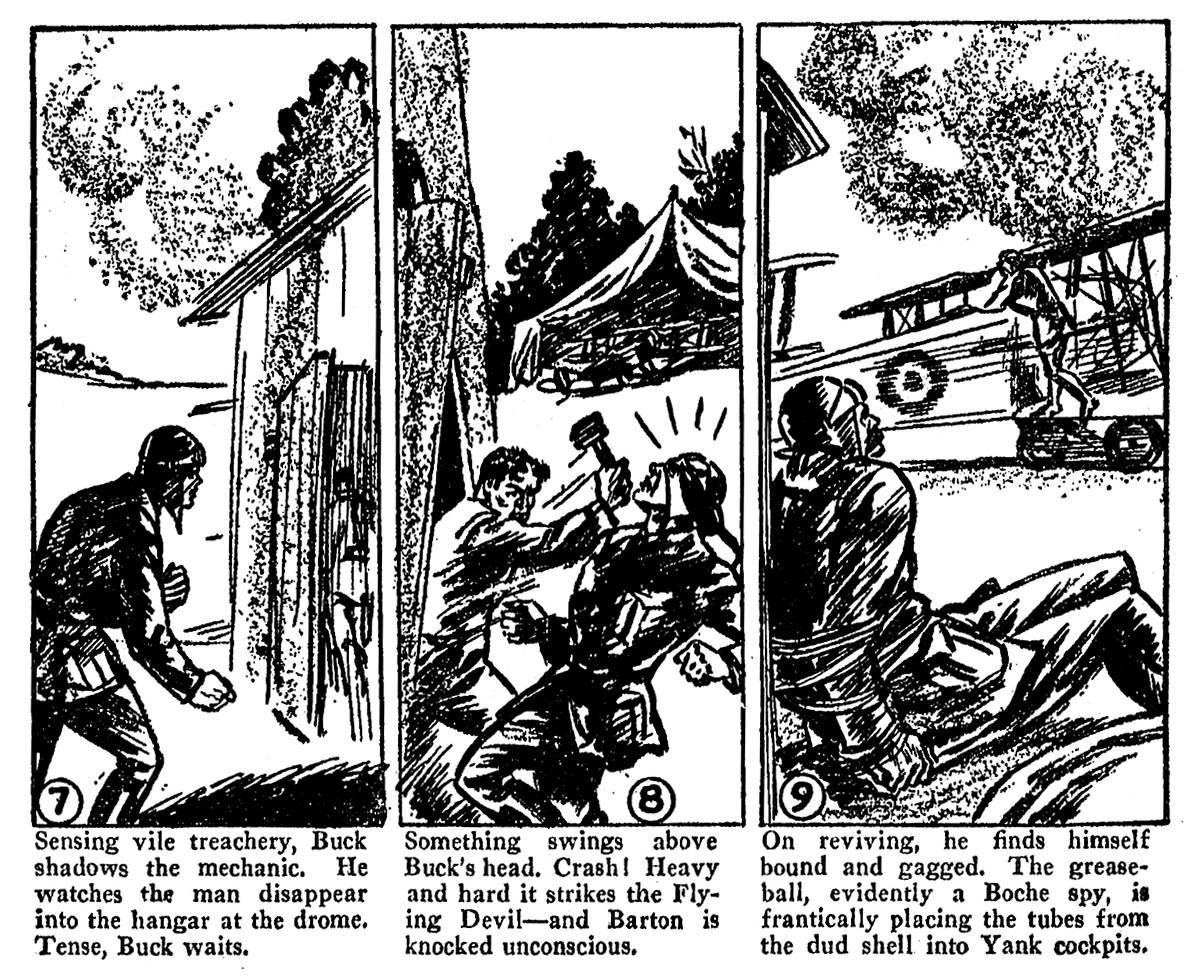

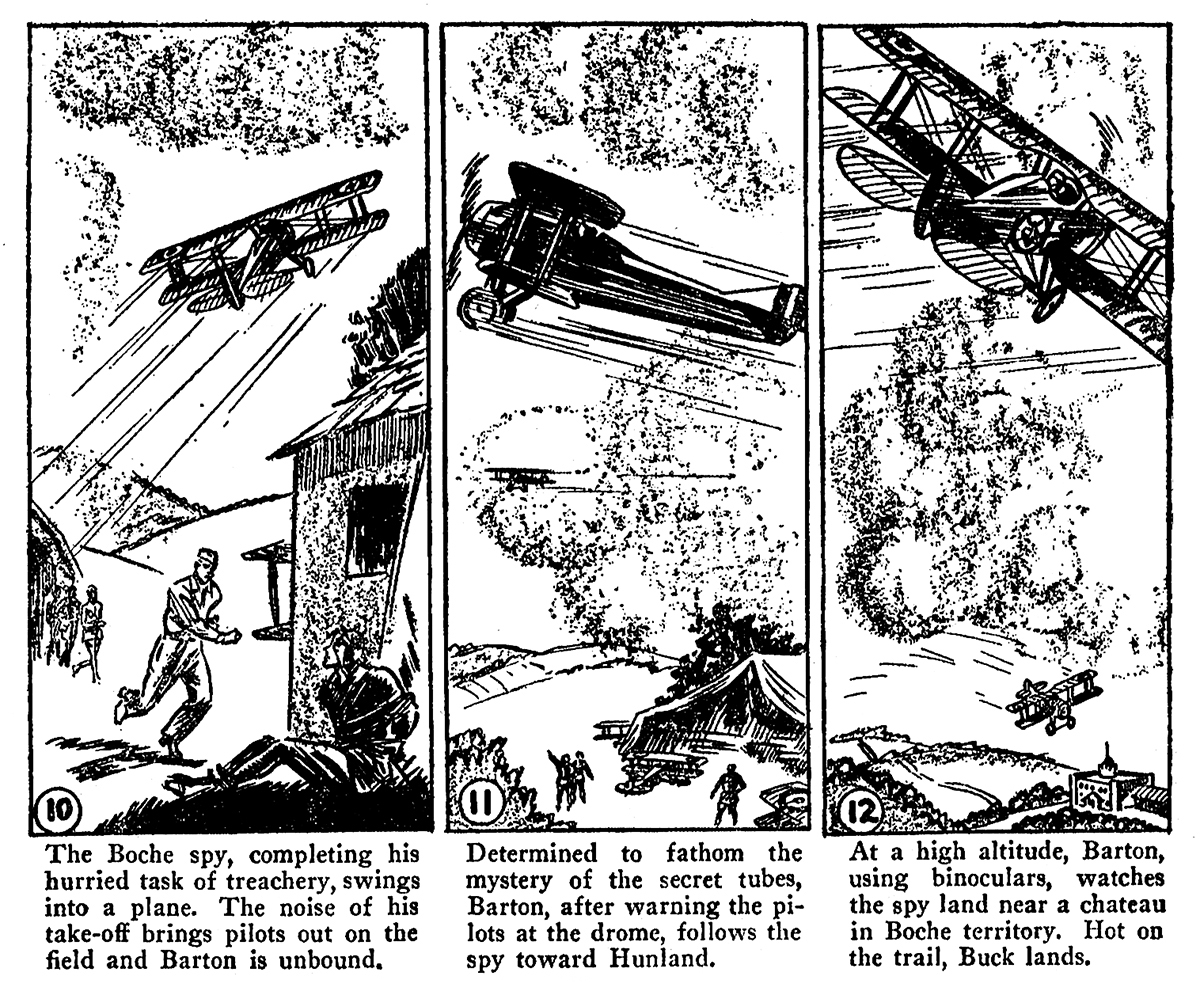

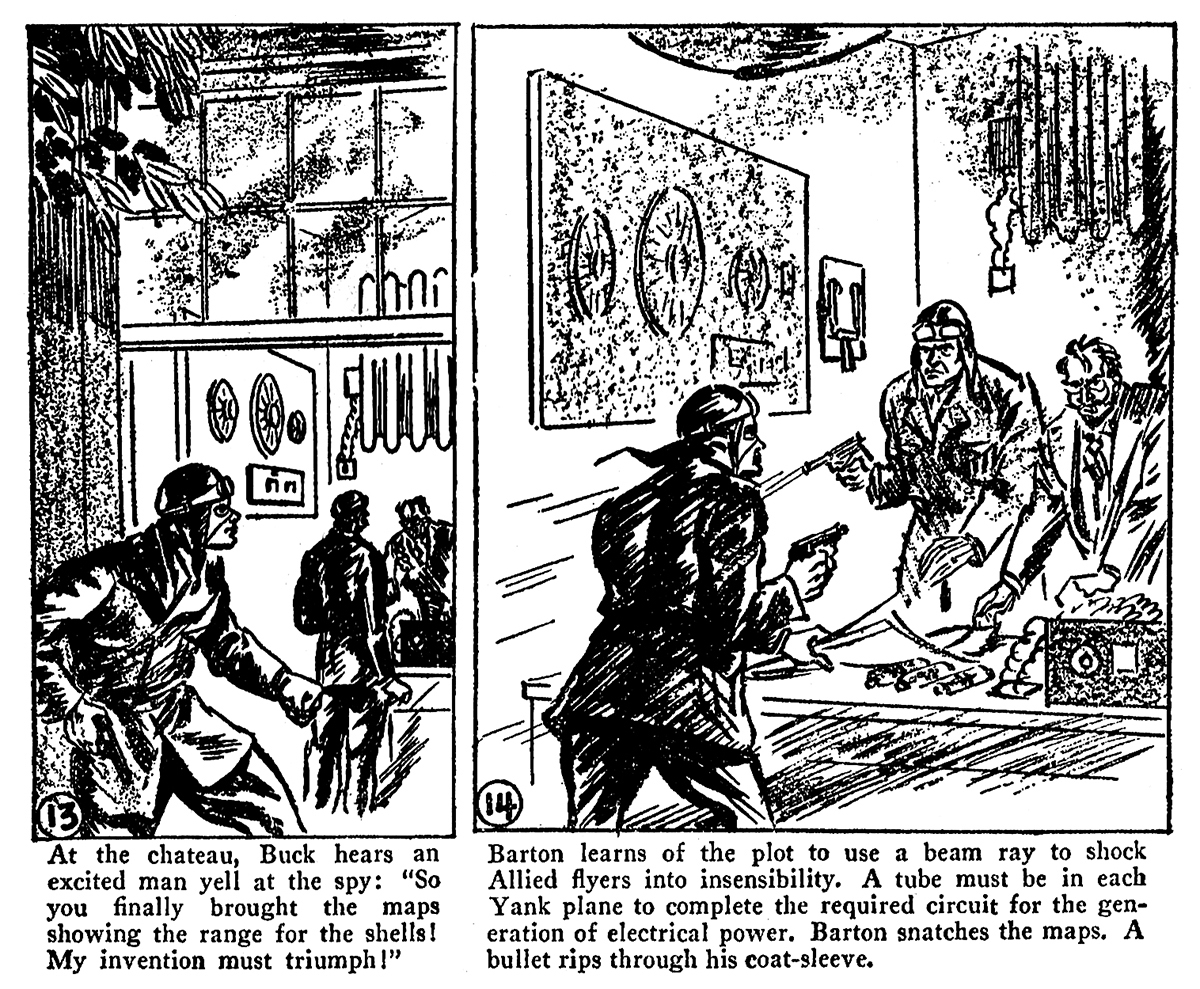

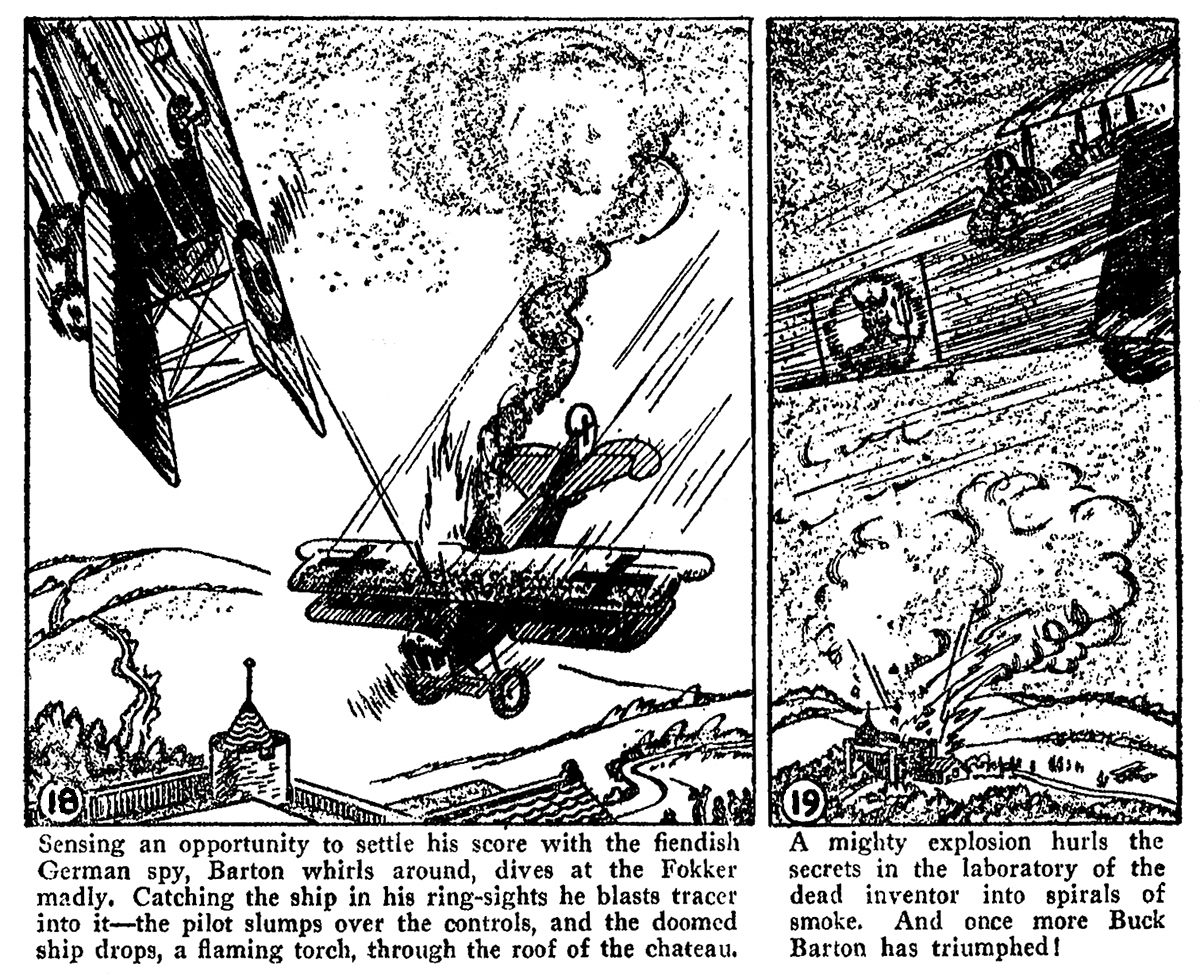

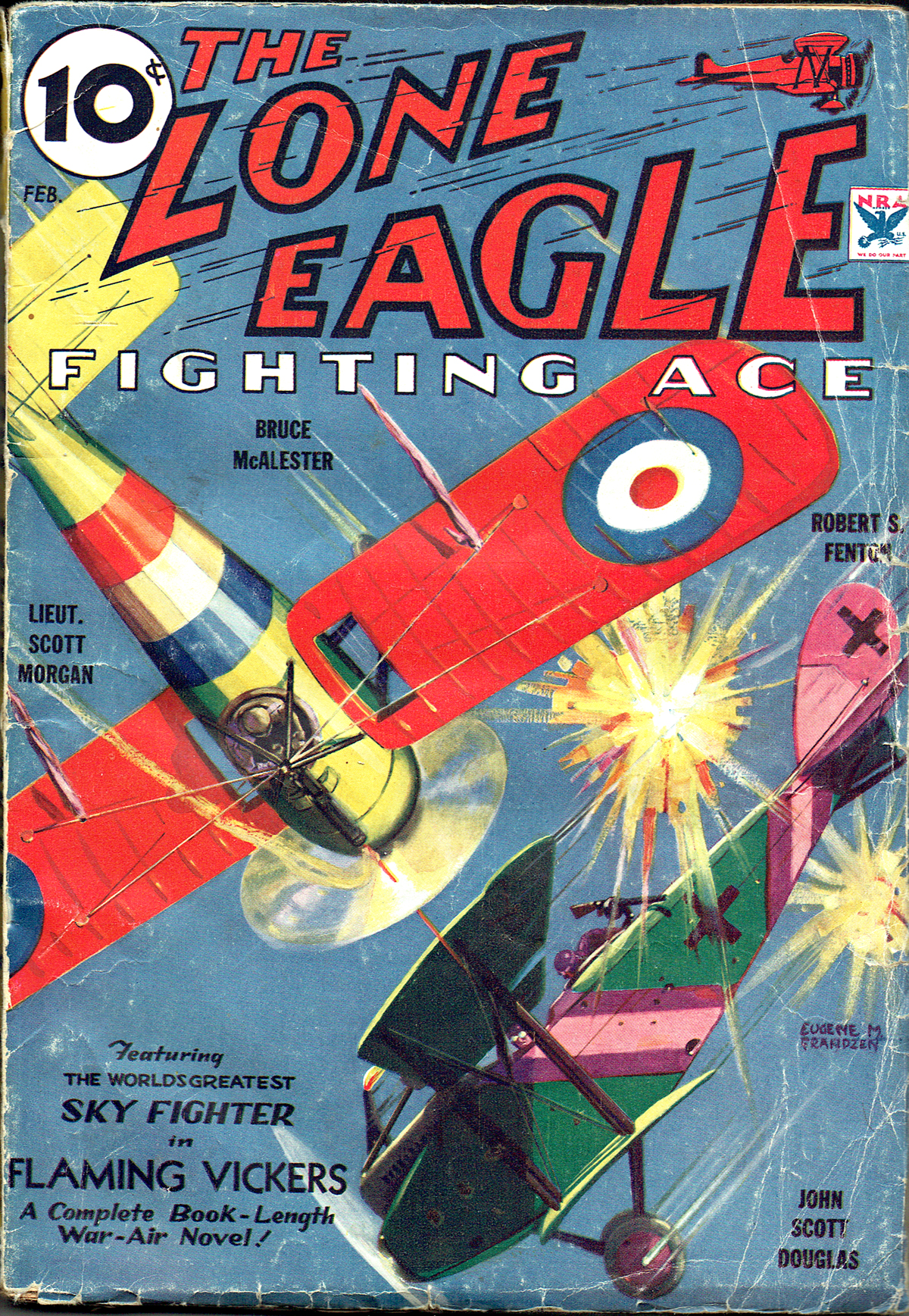

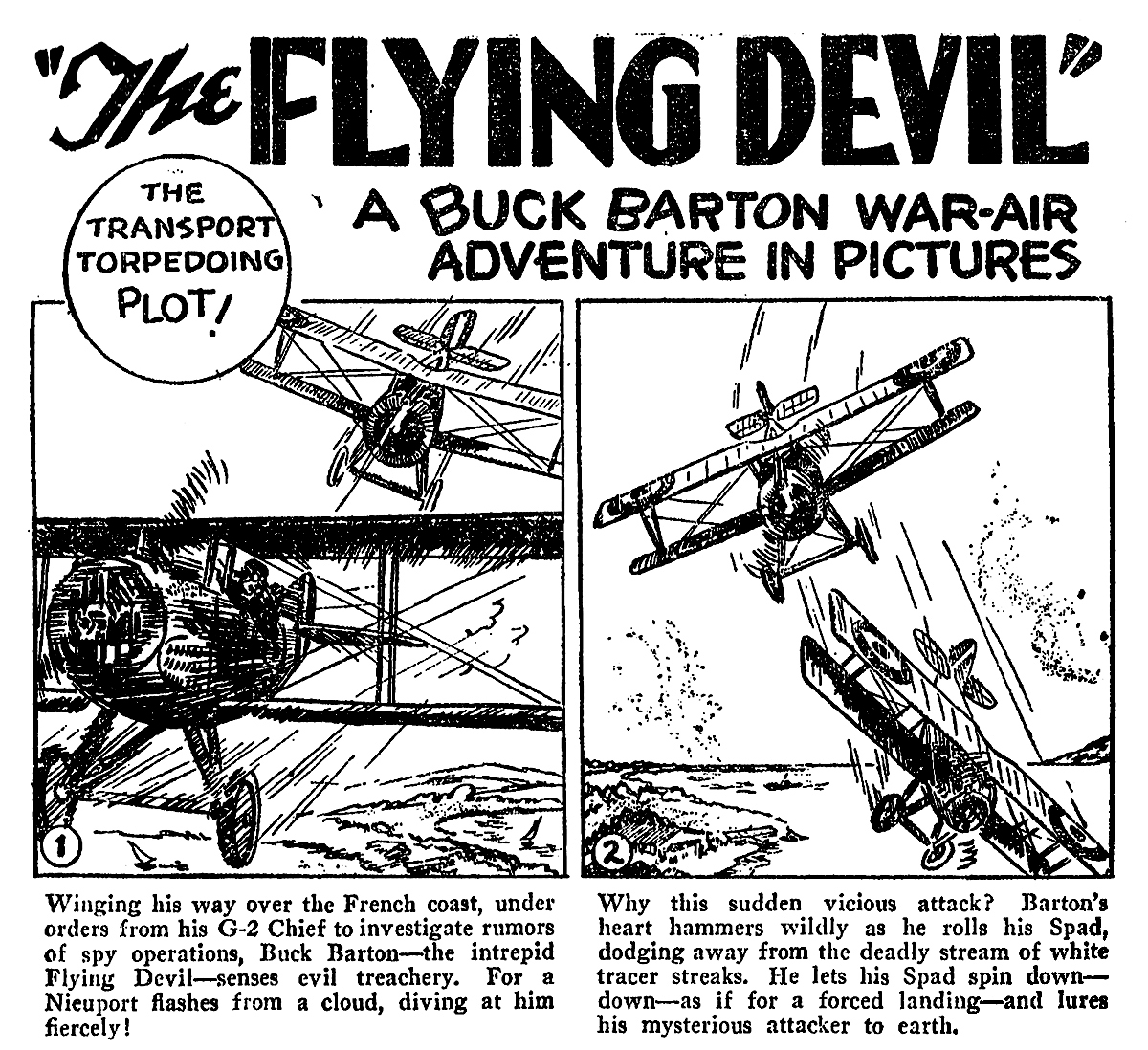

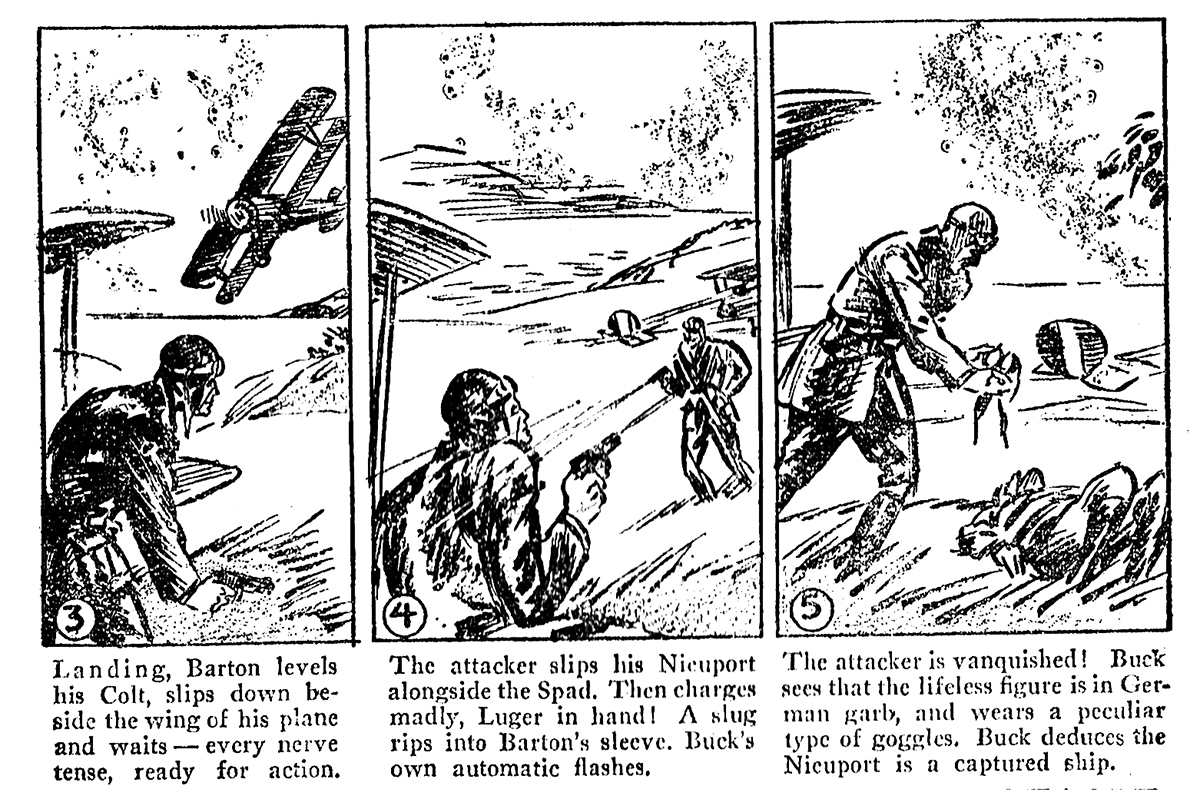

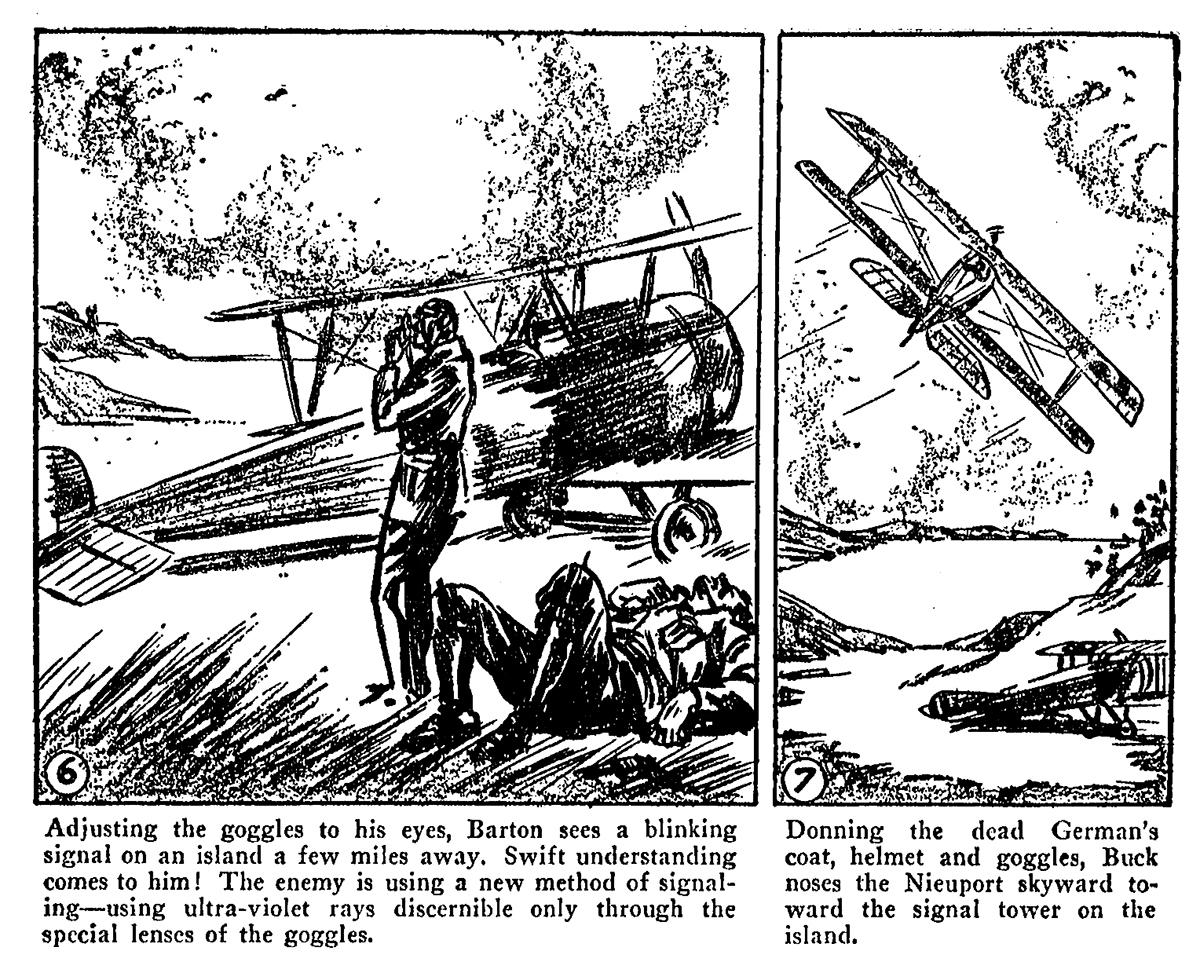

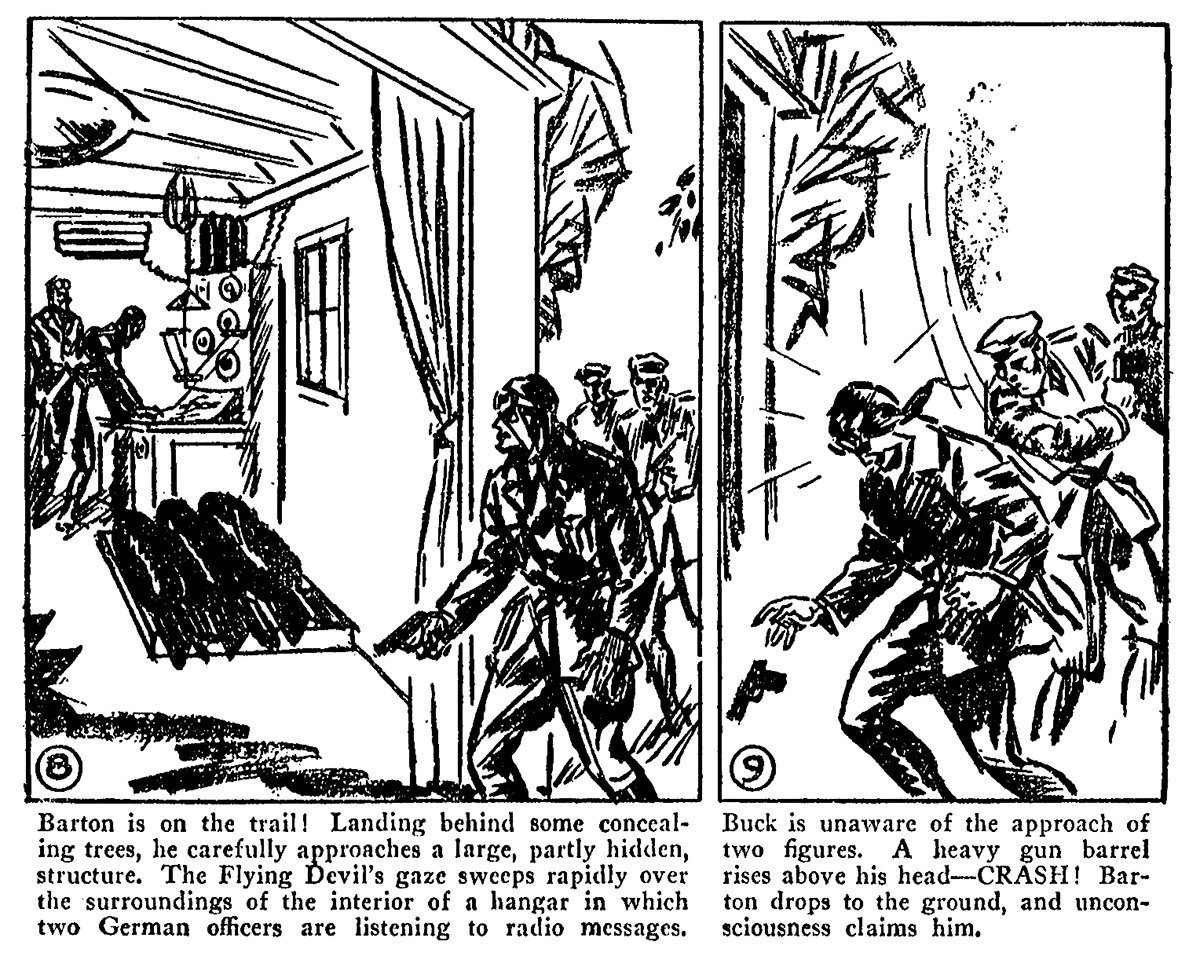

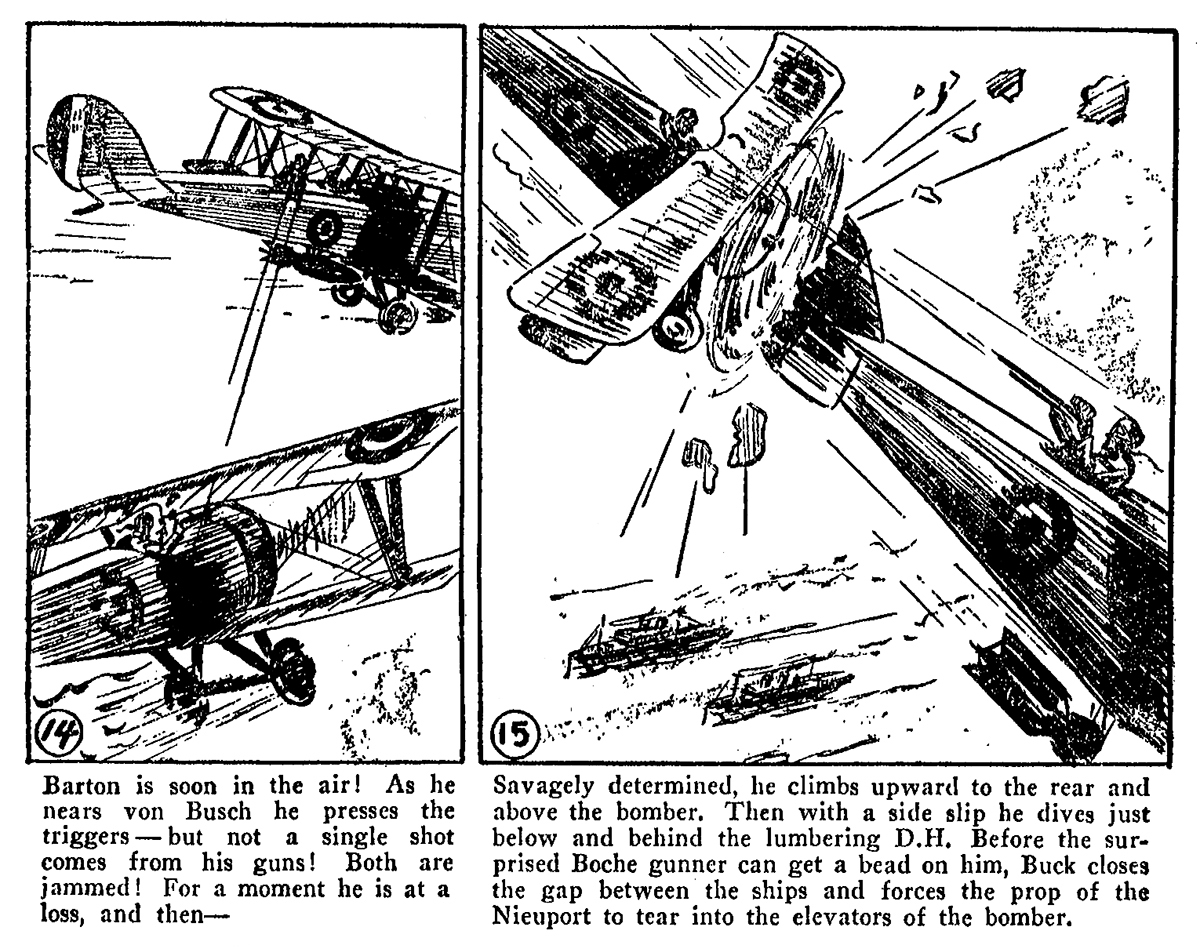

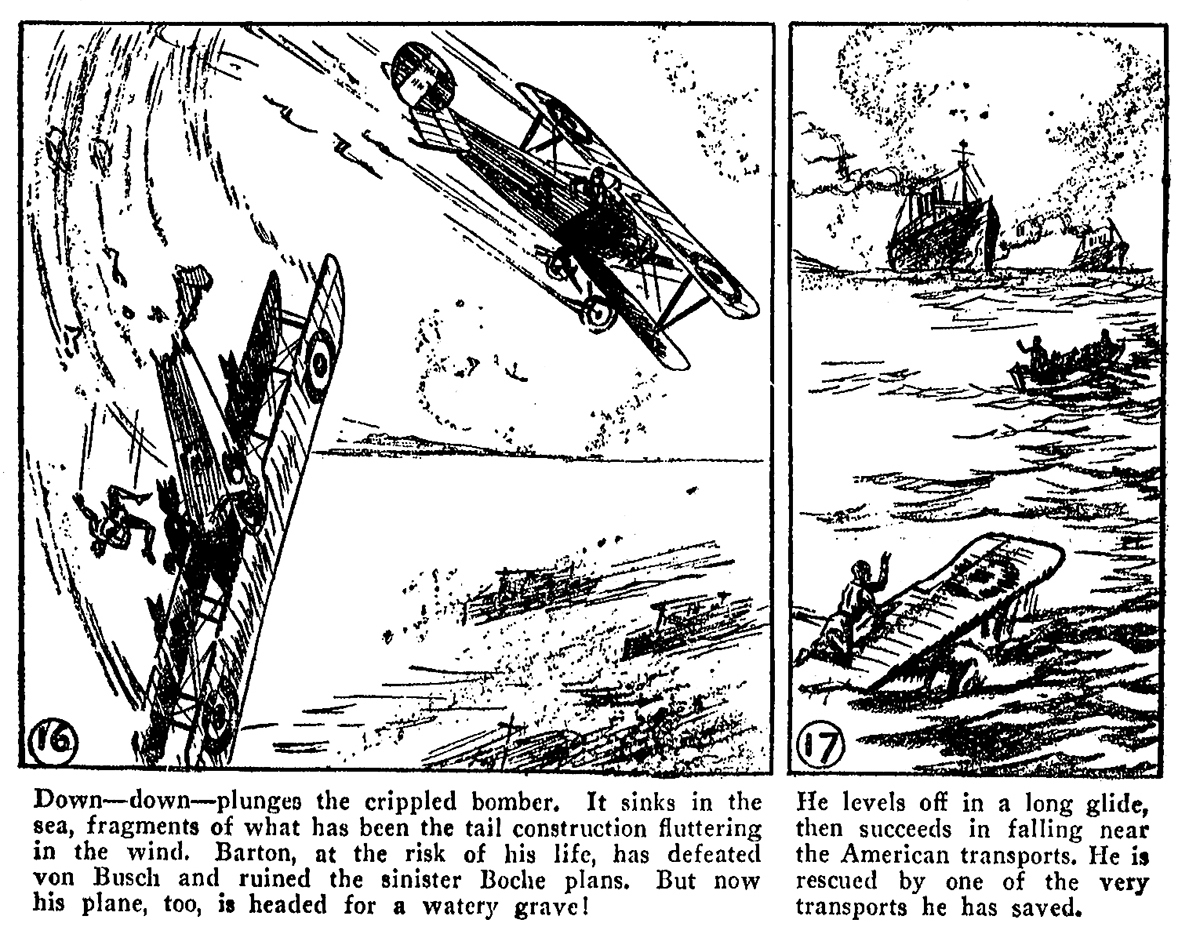

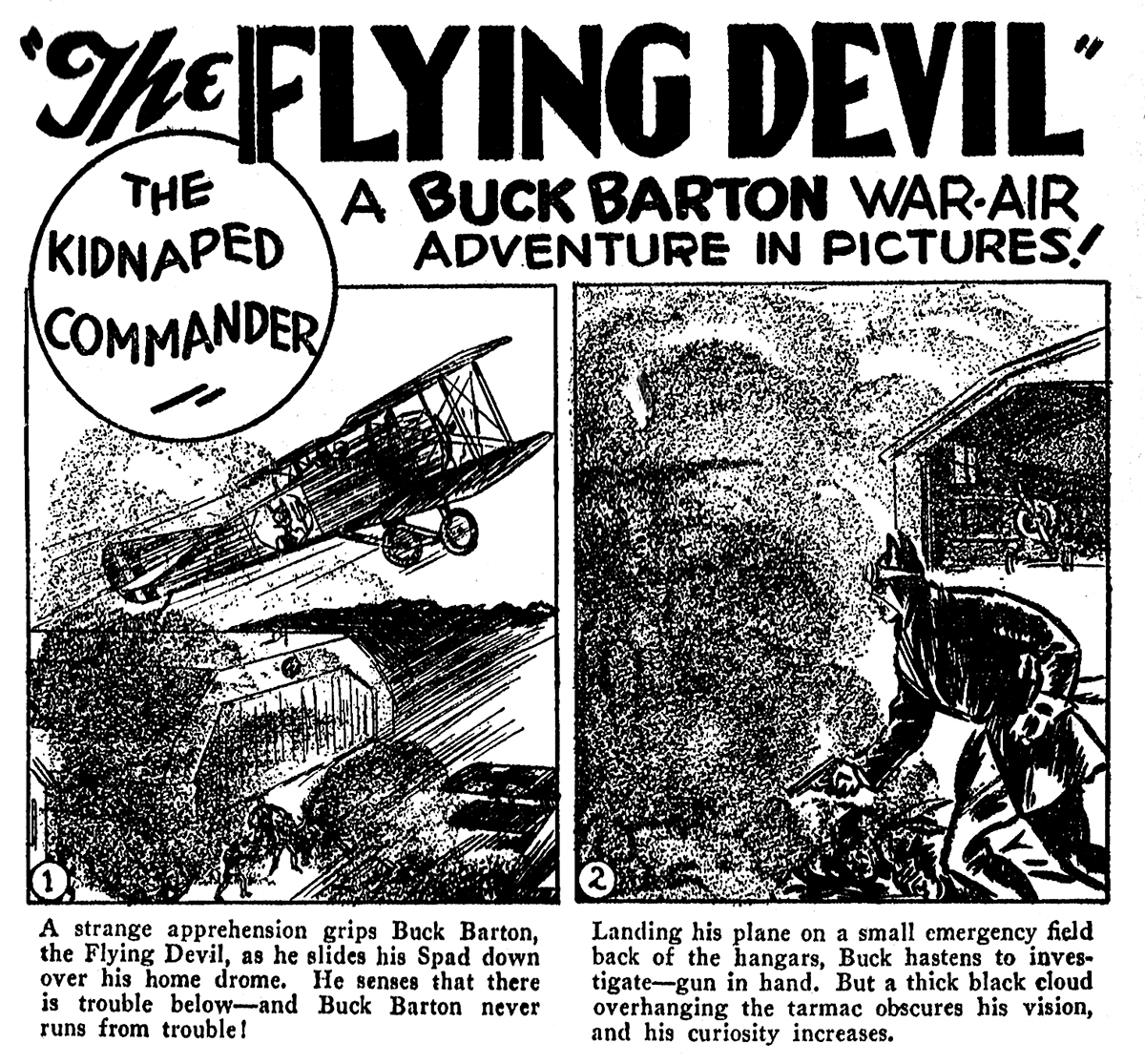

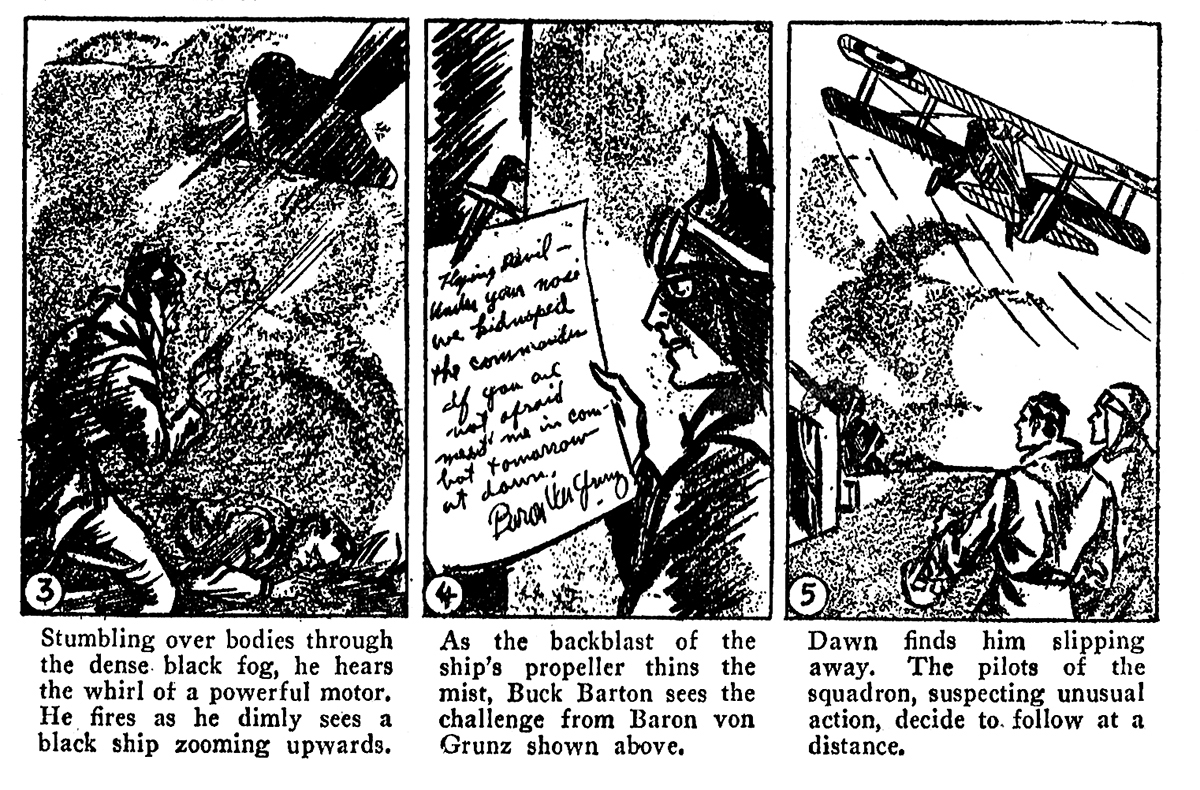

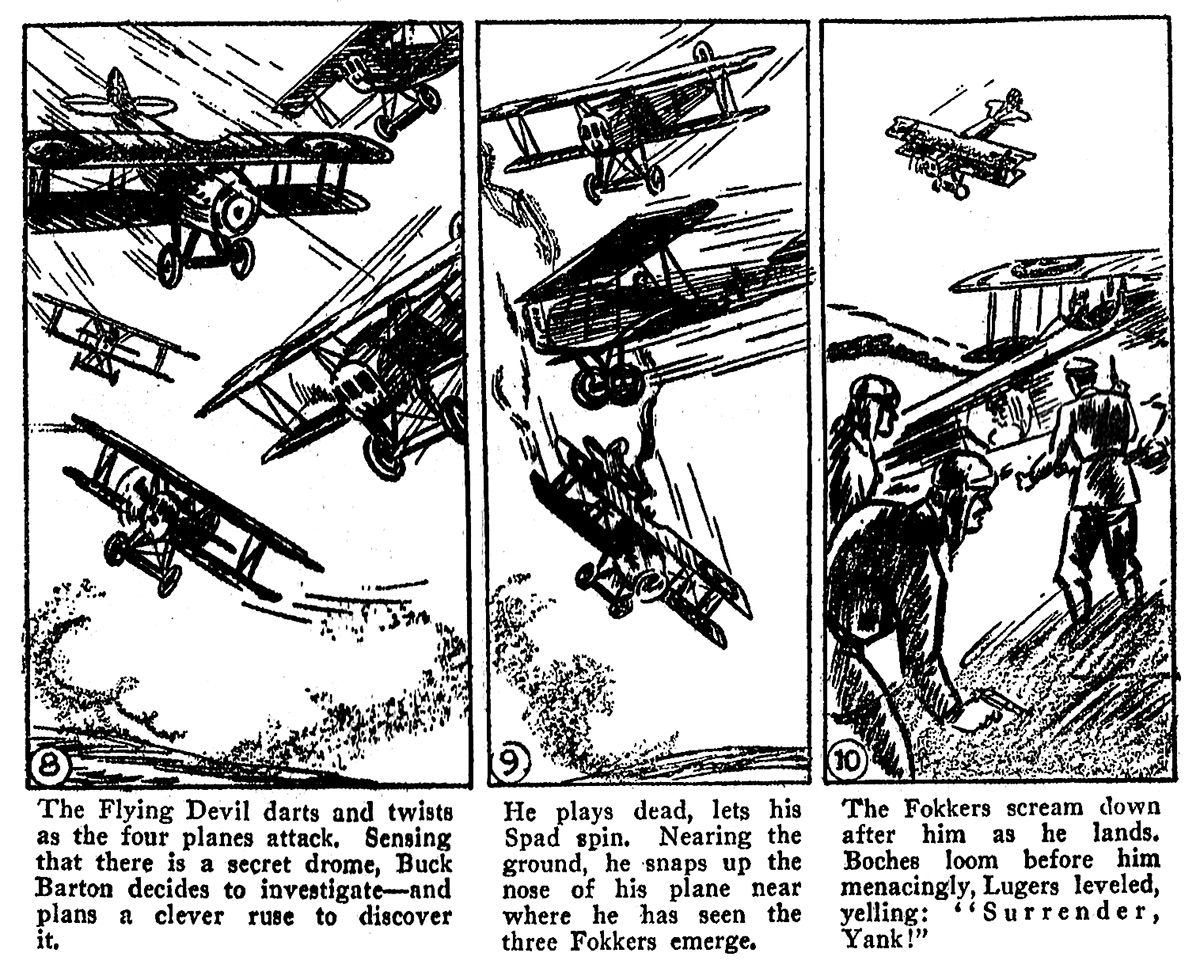

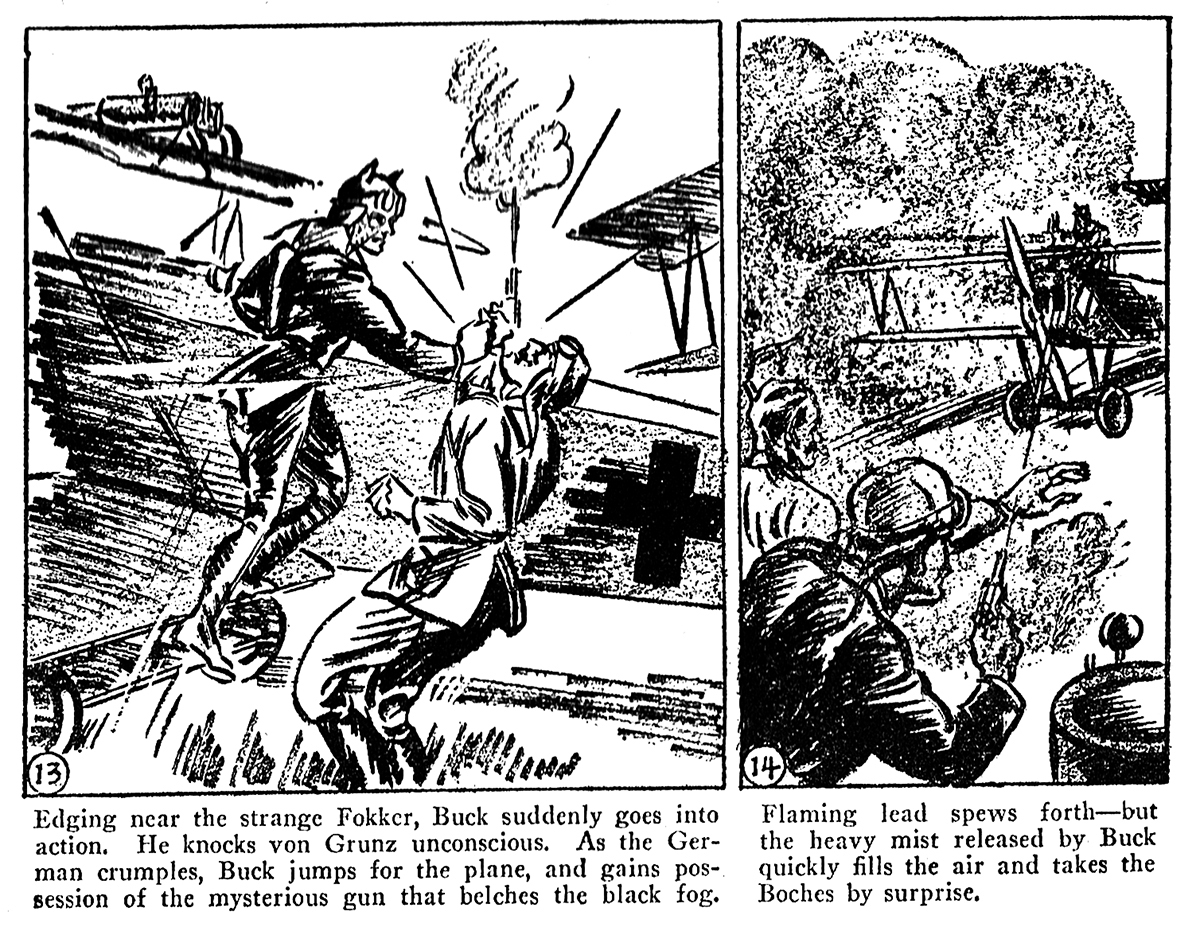

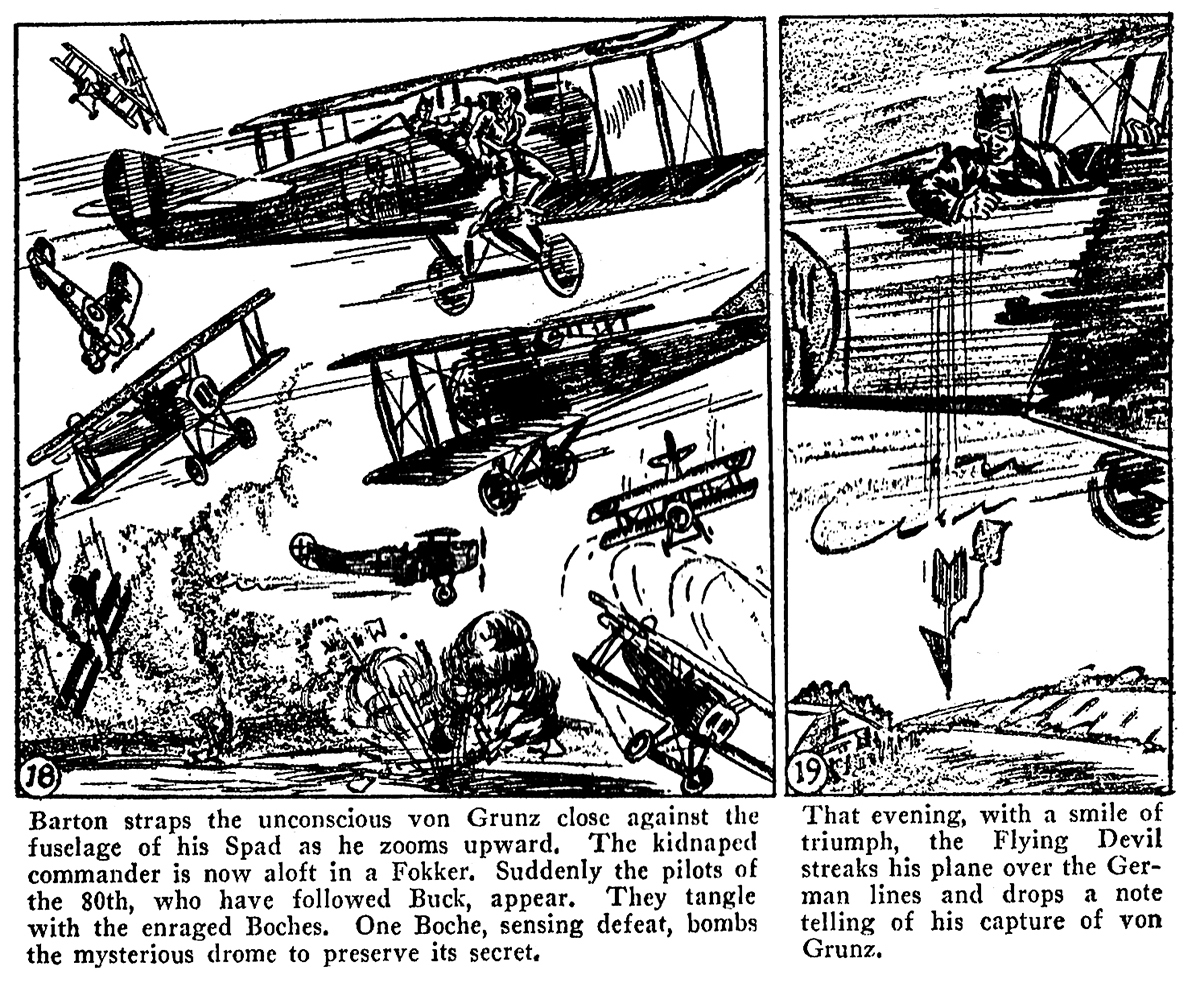

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by Terry Gilkison and features the exploits of Buck Barton, a.k.a. The Flying Devil, as he wages a one man war against the Germans in his Spad with the devil on the fuselage.

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by Terry Gilkison and features the exploits of Buck Barton, a.k.a. The Flying Devil, as he wages a one man war against the Germans in his Spad with the devil on the fuselage.

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

in on The Flying Devil! The Flying Devil was a regular feature of the first fifteen issues of The Lone Eagle and, more importantly, as they announced beneath each month’s story—“the Only War-Air Cartoon Story to Appear in Any Magazine!” The strip was drawn by

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.