“Mannock, The Mad Major!” by Paul Bissell

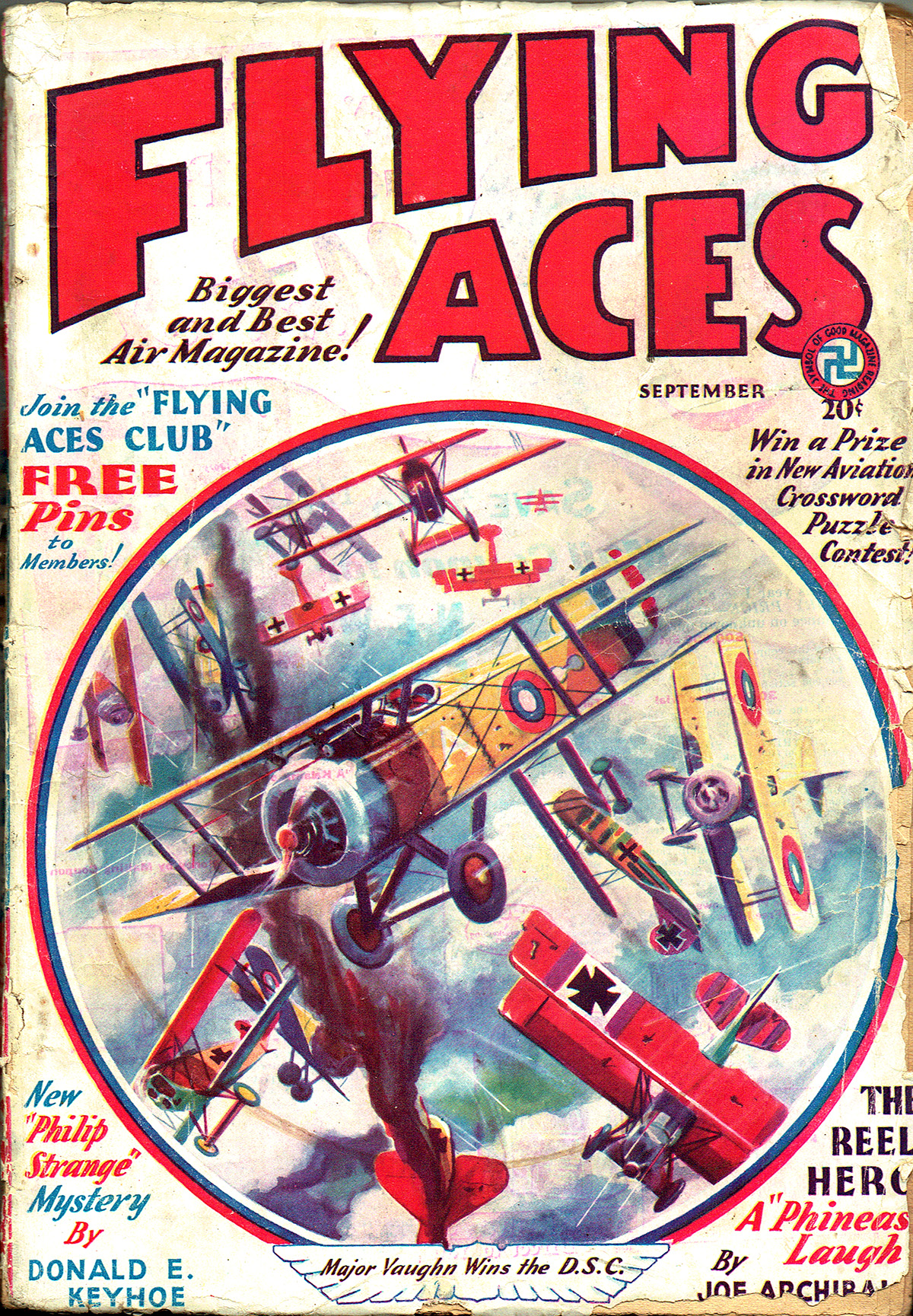

THIS week we present another of Paul Bissell’s covers for Flying Aces! Bissell is mainly known for doing the covers of Flying Aces from 1931 through 1934 when C.B. Mayshark took over duties. For the December 1932 cover Bissell put us right in the action as Major Edward Mannock gives his all

Mannock, the Mad Major!

FROM the war have come many nicknames which have since been applied rather freely to others besides those who originally earned them. “Crashing Colonels,†“Red Barons,†etc., are now commonplace, and to definitely determine the originals of these titles is almost impossible. However, there is one man, who, if we judge by the consensus of opinion in those places where airmen gather, enjoys his soubriquet without argument or question.

FROM the war have come many nicknames which have since been applied rather freely to others besides those who originally earned them. “Crashing Colonels,†“Red Barons,†etc., are now commonplace, and to definitely determine the originals of these titles is almost impossible. However, there is one man, who, if we judge by the consensus of opinion in those places where airmen gather, enjoys his soubriquet without argument or question.

He was a man who started the war as a prisoner of the enemy, was repatriated because of defective eyesight, and lived to prove his eyes the most deadly, searching, and accurate of those of all the airmen who flew for the British, while his irrepressible humor and daredevil recklessness earned for him the name of the “Mad Major.â€

On May 7, 1917, the failure of Captain Ball to return from a patrol held the attention of the Allied world. On the same day, unnoticed, the reports show the destruction of an enemy balloon by a Lieutenant Edward Mannock of Squadron 40. No one cried, “The King is dead, long live the King!†Yet well they might have, for this was the first victory of “Micky†Mannock, the “Mad Major,†one of the mysteries of the World War.

Micky, who was to tear through the skies of France like a thunderbolt, leaving a trail of victories surpassing even Captain Ball’s. Micky, who was to become Britain’s ace of aces, with 73 planes to his official credit, and who was to die, known only to his comrades, unfeted and unsung, with only an M.C. as a decoration from his country.

To be sure, the D.S.O. was going through at the time, and posthumously two bars and the V.C. were finally awarded, but even to this day this great ace is little known to the public at large, and it is difficult to learn a great deal about him.

Mannock’s comrades knew that he had been imprisoned by the Turks at the beginning of the war. He had been repatriated, and enlisted at once with the British, serving first with the R.A.M.C., then with the engineers in France, and coming finally to Squadron 40 in April, 1917.

It was soon evident that he was a Hun-hater, one of the few among all the aces. He was not the sportsman type, to whom war was just a game with death as the stake. Nor was he the hunter type, seeking only the joy of the kill. To him the war was “open season†on Germans, and he was out to exterminate them as he would rats or other vermin. He asked no quarter nor gave any, and yet his irrepressible sense of humor and love of a joke was constantly bobbing up.

He it was who, after failing for several days to get the Germans to engage him in battle, dropped a pair of boots on their airdrome with the note attached, “If you won’t come up and fight, maybe you can use these on the ground.â€

With his M.C. came his captaincy, and he was made squadron commander. He was older than most aces, being thirty at his death, and he was noted for the care he took of his “new†men. He watched over them carefully, and tried to arrange it so that they would get a victory the first time over. Failing this, he would take them out alone and, finding their victim, he would maneuver the German into a good position for the new pilot’s fire. Then, making sure by a few bursts from his own guns, he would return to the drome, where he would enthusiastically congratulate the fledgling on getting his first German. It is said, in fact, that more than one ace-to-be had his first victory handed him by Micky.

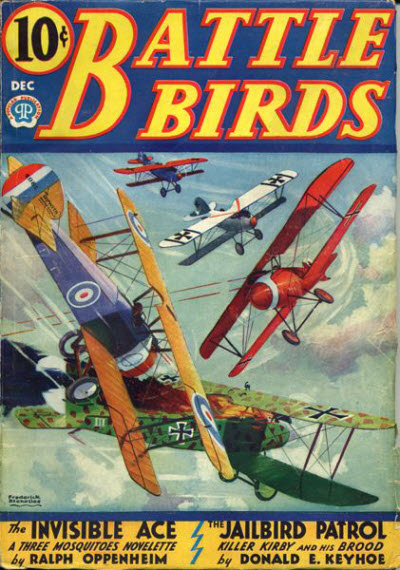

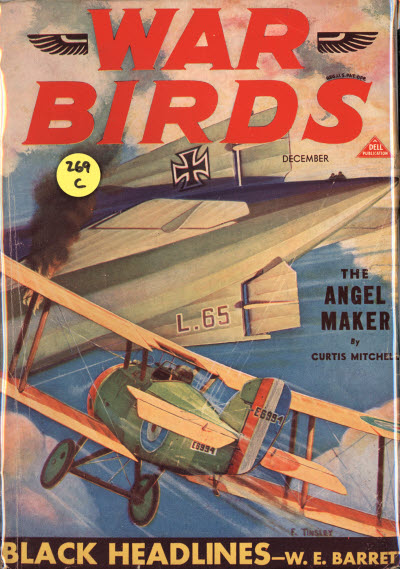

IT IS told, also—and this story is pictured on this month’s cover—that on one of these excursions he gave the mud-covered Tommies in the trenches the thrill of their lives. He and his fledgling had spotted their victim and after some maneuvering Micky had finally forced the German into a position for his youngster to make the kill.

At this instant from the clouds dropped a red Albatross—motors on, and its-tracers already reaching hungrily for the new pilot below. A yank of the stick and Micky had thrown himself square into the line of the Albatross’ fire to save his companion. Bullets crashed through his cockpit and seared holes in his wings, but the German’s dive had been headed off, and a moment later, coming out of a mad vrille, the little S.E.5’s nose was square on the red tail with the black cross.

The Vickers rattled, and the German sped on down to pile up in a trench, while Micky turned back to the battle above. The youngster had failed to get his opponent at the first burst, and the more experienced German by clever flying had gotten himself into a good position for attacking the kid pilots.

However, seeing Micky return to the fray, the German decided to run for it, and turned toward Germany, but little did he know his opponent. The Irishman seemed to go wild. He flung his little S.E.5 after the fleeing Boche and quickly overtook him. Then, to the astonishment of those who watched below, Micky held his fire. Steeply he dived in from the side, forcing the German to turn. But again the Vickers were silent. Apparently the German decided that Micky’s guns were jammed, for he made a desperate attempt to turn to the attack.

Immediately, however, the twin Vickers spoke, spitting hot lead, and forcing him to swing back around. Then to the watching Tommies the game became evident. Like a cat with a mouse the Irishman was playing with the German. Slowly he was forcing the Albatross down.

Lower and lower they came. They were scarcely 100 feet up, and below them was the wrecked remains of the first plane, when suddenly the twin Vickers began chattering. The desperate Jerry swung right and left, only to be met by the deadly hail of bullets from the S.E.’s gun. Then one last burst and those below saw the German jerk from his seat, clawing the air madly in his death agony as his plane crashed, its wings touching the wreckage of the first Albatross.

Two more for Micky! No wonder they called him the Mad Major! And so it went, until, on a similar expedition in July, a machine-gun bullet from the ground found him. At least that’s one version. A second story says that he crashed a German to save one of his fledglings. It was another mystery, but the fact remains that no more would his comrades see him tuck his violin under his chin, and while they sat enthralled, play, “Where My Caravan Has Rested.†For the Mad Major had led his last caravan home.

“Mannock, The Mad Major!â€

Flying Aces, December 1932 by Paul J. Bissell

Canada’s very own

Canada’s very own  Canada’s very own

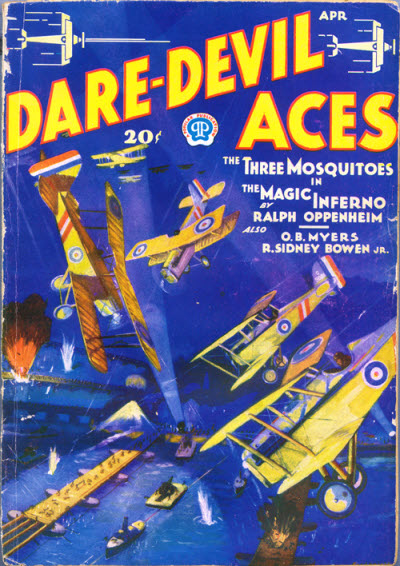

Canada’s very own  We’ve collected and published all 29 of The Sky Devil’s stories from Dare-Devil Aces into two volumes—

We’ve collected and published all 29 of The Sky Devil’s stories from Dare-Devil Aces into two volumes— magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing R. Sidney Bowen to conduct a technical department each month. It is Mr. Bowen’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Mr. Bowen is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot of the Royal Air Force, but also because he has been the editor of one of the foremost technical journals of aviation.

pen of the Navy’s own

pen of the Navy’s own

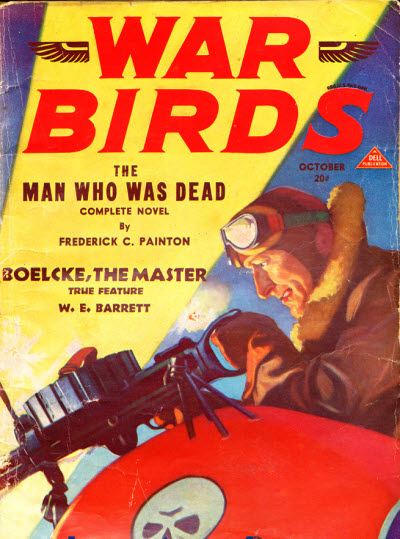

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the

a story from the pen of a prolific pulp author O.B. Myers! Myers was a pilot himself, flying with the 147th Aero Squadron and carrying two credited victories and awarded the

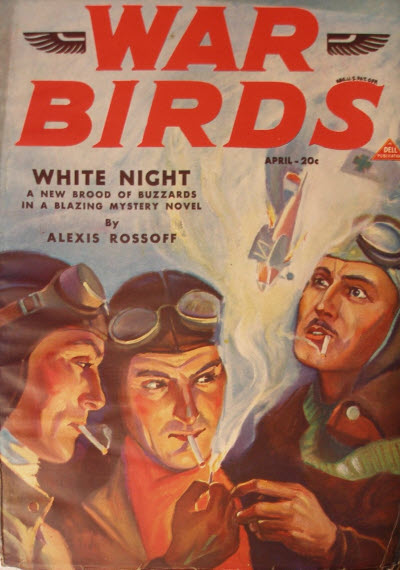

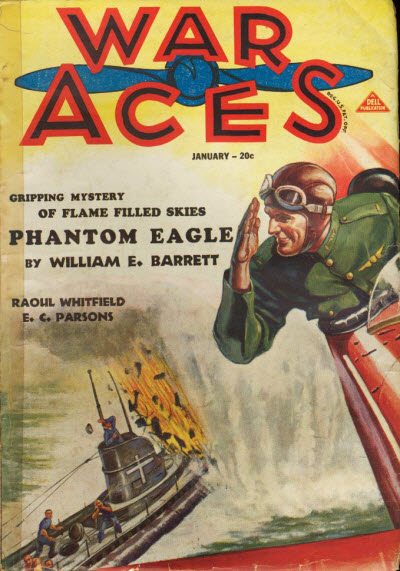

in the January 1932 War Aces—”Unless we misjudge the reading taste of our readers we feel that “Phantom Eagle,†by W. E. Barrett is about the ideal story. It has that balance of action, mystery and fantasy that gives you a new set of thrills. Obviously, it was too bizarre to be entirely fiction, so we asked the author about it. As is the case with most of Barrett’s fiction, it is based on some true incident. Here is his letter:

in the January 1932 War Aces—”Unless we misjudge the reading taste of our readers we feel that “Phantom Eagle,†by W. E. Barrett is about the ideal story. It has that balance of action, mystery and fantasy that gives you a new set of thrills. Obviously, it was too bizarre to be entirely fiction, so we asked the author about it. As is the case with most of Barrett’s fiction, it is based on some true incident. Here is his letter:

a story by Raoul Whitfield! Whitfield is primarily known for his hardboiled crime fiction published in the pages of Black Mask, but he was equally adept at lighter fair that might run in the pages of Breezy Stories. We’ve posted a few of his Buck Kent stories from Air Trails. While the Buck Kent stories were contemporary (1930’s), “The Singing Major” from the January 1932 issue of War Aces is set in The Great War and, in fact, based on a real person. At the time of publication, Whitfield told the editors of War Aces that the legends of this major are still talked about among the peasants in one locality. His was a temperament they couldn’t understand, hence many are the wild stories about him.

a story by Raoul Whitfield! Whitfield is primarily known for his hardboiled crime fiction published in the pages of Black Mask, but he was equally adept at lighter fair that might run in the pages of Breezy Stories. We’ve posted a few of his Buck Kent stories from Air Trails. While the Buck Kent stories were contemporary (1930’s), “The Singing Major” from the January 1932 issue of War Aces is set in The Great War and, in fact, based on a real person. At the time of publication, Whitfield told the editors of War Aces that the legends of this major are still talked about among the peasants in one locality. His was a temperament they couldn’t understand, hence many are the wild stories about him. pen of the Navy’s own

pen of the Navy’s own