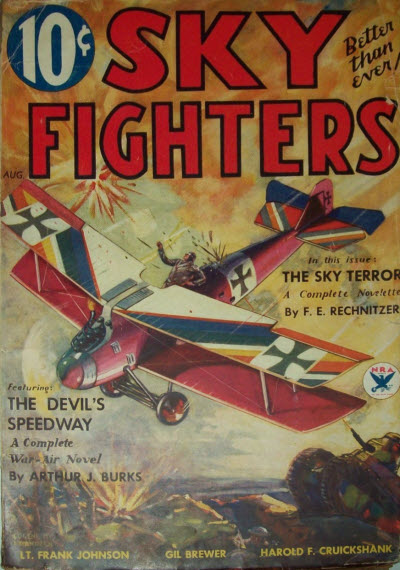

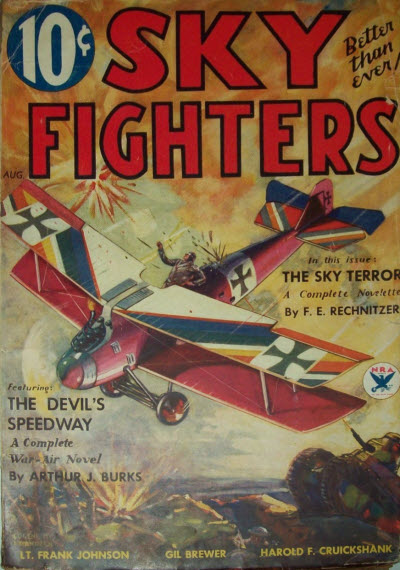

FROM the pages of the August 1934 number of Sky Fighters:

Editor’s Note: We feel that this  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

Wings—and Why

by Lt. Edward McCrae (Sky Fighters, August 1934)

NOW I don’t remember of any of you duck-billed flamingoes stepping up and asking me what it was that made a war crate fly—when it did fly. Maybe it was because you had a suspicion that it was because of the wings. And then again, in case you had guessed that much, I thought maybe you’d be wondering just how it was that the wings sustained the ship, even admitting that you knew that the motor gave it sufficient power to propel itself through air.

Well, if you want to give up and learn something, I’ll tell you something about that today. And while I’m at it I suppose this is the best time to explain why some of the ships were monoplanes and some biplanes and even some of them triplanes, as one of the members of the German Albatross family, and one of our own Curtiss ships, as well as others. Wake up and listen to some real scientific information already predigested so it won’t get stuck in your delicate brains.

The answer Is this; when the ship is driven forward by a motor, the wing is so shaped that the air passes over and under the wing according to the “camber” of the wing. The camber is the shape it is in cross section. Take a look at Fig. 1 and you’ll see what I mean.

You’ll notice that the wing is rounded in front, gets thicker and then tapers to almost nothing at the rear or “trailing” edge. The distance from the front to the back is called the chord of the wings. You will see that the air is diverted upward and forms a kind of vacuum or area of reduced pressure over the wing. And also that some of the air hits the under-surface.

The Lift of the Ship

The lift of the ship is caused by the vacuum over the wing and the upward pressure of the wing on the under surface. And it may surprise some of you knot heads to know that the vacuum above the wing furnishes from three-quarters to in some cases ninety-eight per cent of the lift, and therefore the pressure from underneath furnishes from a quarter down to as little as two per cent of the lift.

Now, during the war the engineers knew that the amount of lift a wing surface had depended somewhat on the thickness of the camber and the shape of the wing. A wing that was thick at its maximum depth would naturally shoot the air higher over the wing and form a greater vacuum and thus give more lift. But when it did that it also reduced the speed.

What they wanted, then, was some way to get around that if they could. So, they knew that the greater the wing surface the greater the lift. If you wanted to lift a thousand pounds you would have to have a certain amount of wing surface of a thin camber, but more surface if the camber was thicker.

They Built More Wings

What is more natural, then, than to build more wings, one on top of the other. Take a look at the Albatross airplane as an example. (Fig. 2)

They had a lot of problems. They wanted ships for speed and carrying light weights. These would be the scouts and fighters. They needed others to carry heavy weights.

So they designed ships with wings like the ones shown in Fig. 3. The wing in 3-A is the section of a bomber. It will lift heavy loads, but it flies slowly because it cuts the air at such a steep angle to the line of flight, and it has a slow speed. 3-B shows a wing that will carry a fairly heavy load, fly a little faster and not land too fast. It was used on some training planes, like the old Curtiss Jenny. 3-C would have a much higher flying speed and would be used for reconnaissance and work that took fast maneuvering. And the last one of the wings would be found only on the fastest ships, fighters that had to get places in a hurry.

I remember the first one of these babies with a flat lower camber that came out to our little orchard at Ypers. Bill Bradley who claimed he could fly anything, looked at it and grunted and said, “Hell, that’s nothing but a barn door equipped with a motor and undercarriage. Crank ‘er up and I’ll fly her, though.” And, listen, Mary Jane, he did just that.

So whenever you’re loafing around a flying field and see a pair of wings that are flat on the under-side, just grab your dresses and run, because that ship can get places.

Now, let’s follow a bird that wants to design an airplane and see how he goes about deciding what kind of wings he’s going to put on it. The first question that comes up, of course, is, what you want it for. Say, for instance, we want it for photographing work, or light bombing. At any rate, we want it to carry about two thousand pounds of weight and make reasonably good speed. We don’t want too much speed in landing because the load it carries is delicate, the machine will be heavy and will have to land slowly.

We’ve Learned by Mistakes

Now we’ve learned by the mistakes of others that the average machine will carry about two-thirds of its own weight, or a ratio of 40 per cent cargo to 60 per cent dead weight. That being the case, the ship we have to build must weigh three thousand pounds in order to carry a useful load of two thousand, a total then for ship and cargo of 5,000 pounds.

Now the next thing is how much lift is needed. We know that for an average speed with an average load, with an average motor, the ship should have a lift of seven pounds for every square foot of wing surface. The problem is, how much wing surface will we need to lift five thousand pounds.

Get out your slate Johnny and figure that out. It’s easy. Just divide the total five thousand pounds by seven and you have about 714 square feet of wing surface needed.

Now, shall we supply that 714 feet all in one wing, or break it up into two wings? We figure this way; engineers have learned that the span of a wing across the front of the ship should be at least five times the chord, or depth fore and aft. Now if we tried to build a monoplane on those proportions and got our whole 714 feet of wing surface in it we would have a wing which would be seventy feet across and about ten feet deep.

They’re All Metal Now

That’s not so much of a problem in these days, because of all metal construction that has been perfected since the war. But in those days we had spruce and linen and wooden and wire construction. So, to have built a ship out of wood and wire with seventy foot wings wouldn’t have been so hot. I can promise you, Tilly, that plenty of ships shed their wings when they weren’t even as broad as our seventy-footer.

So, we’ll cut the wings half in two and give 350 feet square to a top and bottom wing. This will allow us to strengthen each wing by bracing it to the other wires and struts. Now we’ve got two wings that aren’t so flimsy, each fifty feet across and only seven feet deep. That’s more like it.

And that’s the way they went about it. And also, that’s the reason you didn’t see so many monoplanes in the Big fracas. Ships were flimsy things and they had to strengthen them as well as they could.

More Monoplanes Today

The Germans had been experimenting with light metal, however, in their Zeppelins, and before the war was over they had constructed a good monoplane with internal bracing that was strong enough to keep it from shedding its wings. But not the Allies. Of course, after the war, the Allied countries got busy and made up for the lost time, and today you see probably more monoplanes, and certainly in the more expensive ships, than biplanes. It saves a lot of external braces and things that offer resistance to the wind, unless its speed you want.

So that, little children, is how the engineers worked day and night to build ships for men to knock out of the sky, and that’s how they learned to finally build ships that are today safer than automobiles, if you believe in insurance statistics, which always tell the truth.

And here’s another truth—it may be stranger than fiction, that business about a ship being lifted by the top side of the wing instead of the underside—but truth always turns out that way.

So, believe it and like it, you flamingoes, while I go out and rip off a couple of wings.

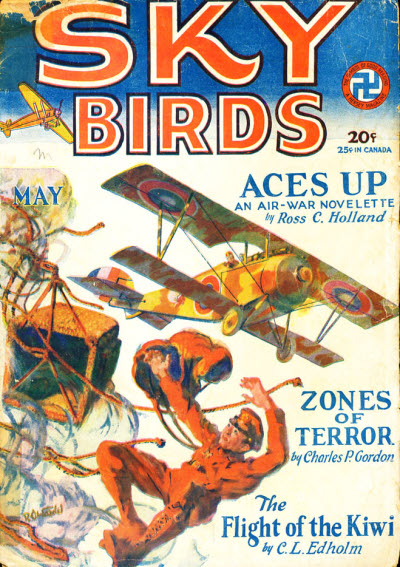

another story from one of the new flight of authors on the site this year—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War and worked for the air mail service upon his return, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the 1920’s through 1950. Here Caffrey tells the tale of Loop Murry, stunt flier for the movies who learns there’s sometime more to a man than meets the eye. From the May 1929 number of Sky Birds, it’s Andrew A. Caffrey’s “The Vanishing Ace!”

another story from one of the new flight of authors on the site this year—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War and worked for the air mail service upon his return, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the 1920’s through 1950. Here Caffrey tells the tale of Loop Murry, stunt flier for the movies who learns there’s sometime more to a man than meets the eye. From the May 1929 number of Sky Birds, it’s Andrew A. Caffrey’s “The Vanishing Ace!”

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

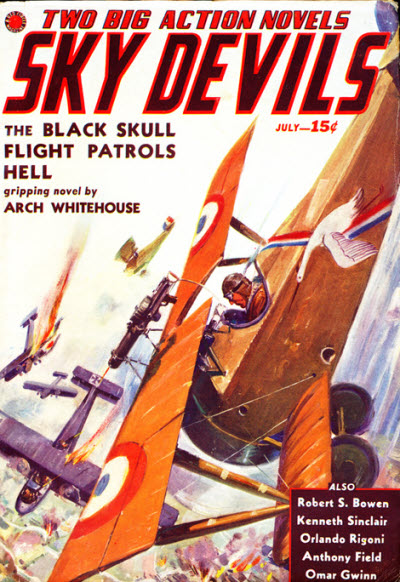

a story by Orlando Rigoni. Rigoni was a very prolific author of western and flying stories appearing in such magazines as Battle Birds, Dare-Devil Aces, Sky Birds, War Birds, Fighting Aces, Sky Fighters, Western Aces, Real Western Round-Up, Thrilling Sports, Air Trails, Western Romances, The Lone Eagle and Flying Acesamong others from roughly 1934 to 1948. He went on to have his stories appear in the slicks; wrote radio and movie scripts; write numerous western novels; and gothic romance novels using the pseudonym “Leslie Aimes.”

a story by Orlando Rigoni. Rigoni was a very prolific author of western and flying stories appearing in such magazines as Battle Birds, Dare-Devil Aces, Sky Birds, War Birds, Fighting Aces, Sky Fighters, Western Aces, Real Western Round-Up, Thrilling Sports, Air Trails, Western Romances, The Lone Eagle and Flying Acesamong others from roughly 1934 to 1948. He went on to have his stories appear in the slicks; wrote radio and movie scripts; write numerous western novels; and gothic romance novels using the pseudonym “Leslie Aimes.” ORLANDO RIGONI, author of “I Want to Know Why” in this issue, appears at the left in a photograph taken in the Yukon last winter while he was working on the Alcan Highway, which, as you doubtless know, is the new road through Canada connecting the United States and Alaska. He is a writer by trade and was working on the road to get material for a novel for young people.

ORLANDO RIGONI, author of “I Want to Know Why” in this issue, appears at the left in a photograph taken in the Yukon last winter while he was working on the Alcan Highway, which, as you doubtless know, is the new road through Canada connecting the United States and Alaska. He is a writer by trade and was working on the road to get material for a novel for young people.

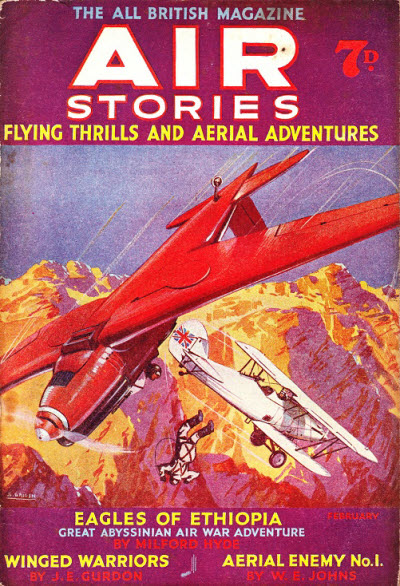

a story from the pen of British Ace,

a story from the pen of British Ace,

exciting air adventure with Rusty Wade from the pen of Frank Richardson Pierce. Pierce is probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger. Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

exciting air adventure with Rusty Wade from the pen of Frank Richardson Pierce. Pierce is probably best remembered for his prolific career in the Western Pulps. Writing under his own name as well as two pen names—Erle Stanly Pierce and Seth Ranger. Pierce’s career spanned fifty years and produced over 1,500 short stories, with over a thousand of these appearing in the pages of Argosy and the Saturday Evening Post.

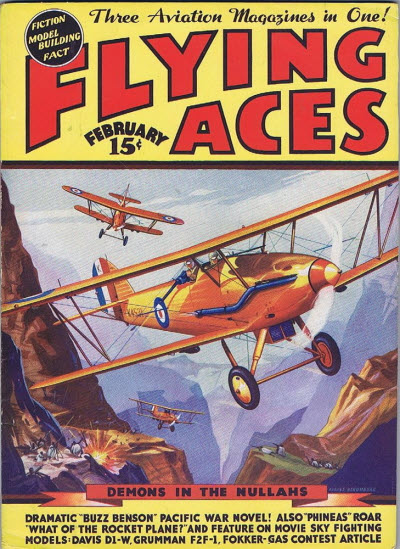

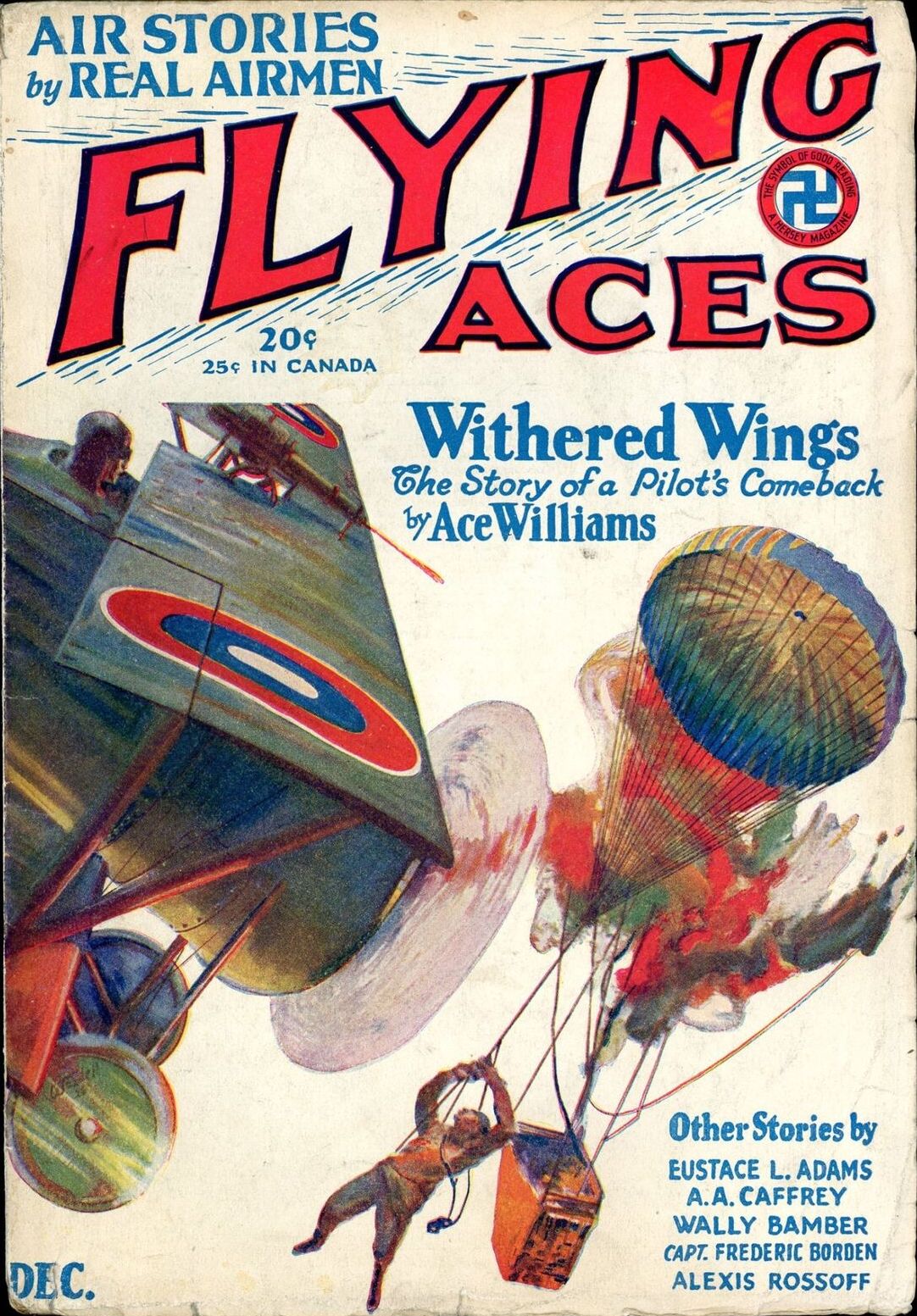

another story by Franklin M. Ritchie. Ritchie only wrote aviation yarns and his entire output—roughly three dozen stories—was between 1927 and 1930. Today we have another one from the lawyer who wrote pulp stories on the side to satisfy his yen for flying. From an early issue of Flying Aces, Ritchie gives us a tale of bomber Jim Barker who longed to show everyone that even a bombing pilot can get Germany’s most ruthless Ace, by any means necessary! From the February 1929 issue of Flying Aces, it’s Franklin M. Ritchie’s “Say It With Bombs!”

another story by Franklin M. Ritchie. Ritchie only wrote aviation yarns and his entire output—roughly three dozen stories—was between 1927 and 1930. Today we have another one from the lawyer who wrote pulp stories on the side to satisfy his yen for flying. From an early issue of Flying Aces, Ritchie gives us a tale of bomber Jim Barker who longed to show everyone that even a bombing pilot can get Germany’s most ruthless Ace, by any means necessary! From the February 1929 issue of Flying Aces, it’s Franklin M. Ritchie’s “Say It With Bombs!” That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

another story from one of the new flight of authors on the site this year—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War and worked for the air mail service upon his return, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the 1920’s through 1950. Here Caffrey tells the tale of Lieutenant Harry Pond.

another story from one of the new flight of authors on the site this year—Andrew A. Caffrey. Caffrey, who was in the American Air Service in France during The Great War and worked for the air mail service upon his return, was a prolific author of aviation and adventure stories for both the pulps and slicks from the 1920’s through 1950. Here Caffrey tells the tale of Lieutenant Harry Pond.  magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

magazine has been exceedingly fortunate in securing Lt. Edward McCrae to conduct a technical department each month. It is Lt. Mcrae’s idea to tell us the underlying principles and facts concerning expressions and ideas of air-war terminology. Each month he will enlarge upon some particular statement in the stories of this magazine. Lt. MaCrae is qualified for this work, not only because he was a war pilot, but also because he is the editor of this fine magazine.

a story by Kenneth Sinclair. Born in 1910, Sinclair had a lengthy run in the pulps. Writing mainly aviation and western stories, his first was in 1932 and his last in 1956. He also published a couple boys adventure novels in the ’50’s where the back covers state Sinclair is a mechanical engineer as well as writer. He died in 1980. “Spandau Salute” finds Terry Ralton going down behind enemy lines convinced that his plane had been tampered with back at the field. If he could just get his hands on that Hawley… And there he was at the German drome he finds himself at!

a story by Kenneth Sinclair. Born in 1910, Sinclair had a lengthy run in the pulps. Writing mainly aviation and western stories, his first was in 1932 and his last in 1956. He also published a couple boys adventure novels in the ’50’s where the back covers state Sinclair is a mechanical engineer as well as writer. He died in 1980. “Spandau Salute” finds Terry Ralton going down behind enemy lines convinced that his plane had been tampered with back at the field. If he could just get his hands on that Hawley… And there he was at the German drome he finds himself at!