“Sky Fighters, November 1936″ by Eugene M. Frandzen

Eugene M. Frandzen painted the covers of Sky Fighters from its first issue in 1932 until he moved on from the pulps in 1939. At this point in the run, the covers were about the planes featured on the cover more than the story depicted. On the November 1936 cover, It’s a S.V.A. coming to chase of a Fokker D6 trying to thwart the Italians from moving a canon between mountains platforms!

The Ships on the Cover

ITALY, before the beginning of the World War, was a potential enemy of the Allies because of her Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria made prior to 1914. On August 1, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia. On that same day Italy renounced her tie to Germany and declared she would stay neutral. But to declare and to actually keep her skirts out of the war muck of blazing Europe were quite different things. On May 24, 1915, Italy declared war on her former ally, Austria. From that day until Austria signed truce terms with Italy on Nov. 3, 1913, the Italian front was the scene of the most dramatic and nerve fraying encounters of the war. Men fought on snowcapped peaks, on slippery sides of glacial formations, on ledges where mountain goats would become jittery. It was slow tortuous labor, this perpendicular scrapping but one in which both sides were familiar.

ITALY, before the beginning of the World War, was a potential enemy of the Allies because of her Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria made prior to 1914. On August 1, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia. On that same day Italy renounced her tie to Germany and declared she would stay neutral. But to declare and to actually keep her skirts out of the war muck of blazing Europe were quite different things. On May 24, 1915, Italy declared war on her former ally, Austria. From that day until Austria signed truce terms with Italy on Nov. 3, 1913, the Italian front was the scene of the most dramatic and nerve fraying encounters of the war. Men fought on snowcapped peaks, on slippery sides of glacial formations, on ledges where mountain goats would become jittery. It was slow tortuous labor, this perpendicular scrapping but one in which both sides were familiar.

The Austrians took an awful beating at the hands of the Italians until October, 1917, when the Austrians launched ferocious counter attacks, driving the Italians back and back. It was not until June, 1918, that the Italians again took the offensive. From then on it was the beginning of the end for Austria.

An Almost Unknown Ship

The Fokker D6 was not given the publicity it deserved and all the glory falling upon the D7 overshadowed it so that it was almost an unknown ship. It did plenty of service on the Western front and was so good that the Allied squadrons who banged into its speedy way were writing it up in their flight reports around the end of 1917. It did most of its damage on the Italian front and the Italians who fought it in their S.V.A. fighting scouts were a couple of minutes behind in climbing to give it battle. A few minutes difference in a plane can mean a lot in the air. The Fokker D6 had an Oberursel engine of 110 h.p. against the S.V.A.’s 210 h.p. Spa motor. It was suicide for the Italians to stage single man duels with that fast moving, supermaneuverable Fokker. So they flew in droves and kept the superior ships from absolutely ruling the skies.

The Austrians knew that supplies which were stored high on the mountain tops were being safely transported by the retreating Italians. The ground forces of Austria had hoped to capture those stores. But mountain fronts are taken by inches and feet, not yards and miles.

Enemy Planes Come Closer

Men who had worked days rigging up a cable across a valley groaned as they watched the enemy planes getting closer and closer to their hidden means of transportating their huge heavy artillery to the rear. One morning at daybreak a giant gun was eased out onto the cable. A gunner rode a swaying platform, a rope tied to each end of the gun ran to mountain peaks between which the gun was to be ferried. Those ropes acted as brakes and motive power for the gun’s movements. The man on the platform signaled constantly to both sides to control the speed and angle of his passage.

As the gun neared the halfway mark in its dizzy trek, the Italian suddenly signaled frantically for full speed ahead. A roaring Fokker D6 was racing up from the valley futilely pursued by an S.V.A. The Austrian pilot’s guns began hammering out lead. The Italian on his swaying perch crouched low. Bullets raked the sides of the cannon, whined off into space. Nearer and nearer raced the enemy plane. The Italian without even a pistol seemed calm in the face of such overpowering odds. His waving hands continued to signal his comrades at the two ends of the cable. For a moment he held one hand extended like an orchestra conductor holding a long note. Then abruptly he dropped it to his side and grabbed the ropes. The men at the drum controlling the cable’s tension understood the signal. They kicked out the rachet guide and the drum raced in reverse, giving out slack.

The Austrian pilot coming up from below sure of a kill and a report to headquarters which would send bombers to wreck the gun transporting equipment, suddenly yanked at his controls as a look of horror flashed in his eyes. Too late! The sagging cable smashed down into the leading edge of his top wing. The cannon and its human cargo lurched and swayed with the impact. The Austrian plane stopped. A twisted mass, it hung for a moment then plunged straight down.

The Italian wiped sweat from his dusky brow, looked over his equipment, nodded approval and gave the signal that would take him and his charge to their destination.

Sky Fighters, November 1936 by Eugene M. Frandzen

(The Ships on The Cover Page)

Mosquito Month we have a non-Mosquitoes story from the pen of Ralph Oppenheim. Lt. Jim Edwards knew he was the worst flyer in the squadron. When the C.O. called him to his office he was sure he was going to be sent to Blois in disgrace—instead the C.O. offers him a mission that could mean spending the rest of the war in a German prisoner of war camp, but when push came to shove, it turns out Edwards could shove with the best of them! From the September 1928 issue of War Novels it’s “Dreadnoughts of the Air!”

Mosquito Month we have a non-Mosquitoes story from the pen of Ralph Oppenheim. Lt. Jim Edwards knew he was the worst flyer in the squadron. When the C.O. called him to his office he was sure he was going to be sent to Blois in disgrace—instead the C.O. offers him a mission that could mean spending the rest of the war in a German prisoner of war camp, but when push came to shove, it turns out Edwards could shove with the best of them! From the September 1928 issue of War Novels it’s “Dreadnoughts of the Air!”

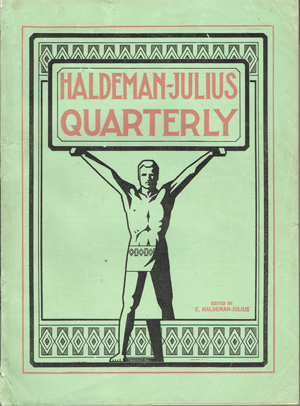

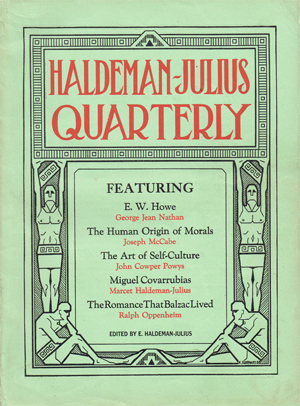

The premiere issue of the Quarterly (October 1926) featured many articles from current and upcoming publications, including Ralph’s “The Love-Life of George Sand.” In some of the early press for the article, they refer to Ralph as being sixteen years old—and, although he could have written it when he was sixteen—he most likely wrote it when he was eighteen, since the hype for it started before he turned nineteen. Ralph’s “The Love-Life of George Sand” article is actually just a reprinting of the 64 page little blue book of the same name. Both the Little Blue Book and the Quarterly were published in 1926.

The premiere issue of the Quarterly (October 1926) featured many articles from current and upcoming publications, including Ralph’s “The Love-Life of George Sand.” In some of the early press for the article, they refer to Ralph as being sixteen years old—and, although he could have written it when he was sixteen—he most likely wrote it when he was eighteen, since the hype for it started before he turned nineteen. Ralph’s “The Love-Life of George Sand” article is actually just a reprinting of the 64 page little blue book of the same name. Both the Little Blue Book and the Quarterly were published in 1926.

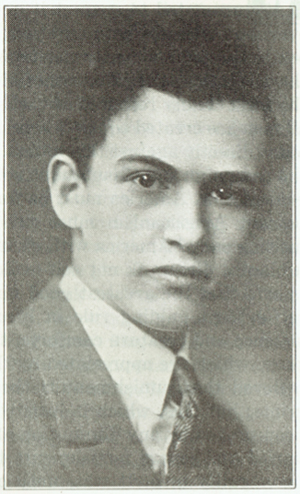

THE author of “The Love-Life of George Sand” is nineteen years old. Here is one of America’s future authors already at work, beginning to express himself with freshness and vigor, with finish and style; an artist to the tips of his fingers. It is one of the purposes of the Quarterly to bring out the best work of young America, and in accepting Ralph Oppenheim’s study we believe we are giving space to material of first-rate significance. This essay compares favorably with the best work we have ever accepted from mature, experienced writers. We did not take Ralph Oppenheim’s manuscript because he happens to be only a boy in years; rather were we influenced by the sureness of his touch. His age came up for comment only after we were satisfied that his work was well done. . . The Quarterly boasts that all in America is not jazz, noise and fury; a minority speaks vigorously and clearly, with intelligence, understanding, humor and craftsmanship. Ralph’s essay helps prove this assertion. Read young Oppenheim’s study and you will realize how important it is for the United States to have a magazine the purpose of which will be to go out and seek for the best from the talented and intelligent minority, bringing out new gifts, fresh viewpoints and sound work. First credit must, of necessity, go to Ralph himself; second credit must go to his artist-mother, Gertrude Oppenheim, and his poet father, James Oppenheim; third credit, in all fairness, must go to the Quarterly for opening its columns to a new voice. America will hear much from Ralph Oppenheim. He has something to say; he knows how to say it; he is a civilized human being, a complete answer to the charge that all of America has been reduced to stifling mediocrity, to unimaginative standardization. There is enough to complain about, in all truth, without crying that all is lost. Let us protest against the viciousness and stupidity of the superstitious majority, the hypocrisy and cowardice of its leaders, the mawkishness of our bunk-ridden millions—yes, let us aim our spitballs at our shams and fakirs, but let us, by all means, recognize worthy talent when we see it and lend an ear to the emerging youngsters who are breaking away from the herd and learning to stand as free individuals. Turn now to Ralph’s essay. At first you will marvel that it was written by a boy, but after a few paragraphs you will forget its author and fly along with his tonic and captivating work. . . . The portrait of George Sand was drawn especially for the Quarterly by Mrs. James Oppenheim, Ralph’s mother.

THE author of “The Love-Life of George Sand” is nineteen years old. Here is one of America’s future authors already at work, beginning to express himself with freshness and vigor, with finish and style; an artist to the tips of his fingers. It is one of the purposes of the Quarterly to bring out the best work of young America, and in accepting Ralph Oppenheim’s study we believe we are giving space to material of first-rate significance. This essay compares favorably with the best work we have ever accepted from mature, experienced writers. We did not take Ralph Oppenheim’s manuscript because he happens to be only a boy in years; rather were we influenced by the sureness of his touch. His age came up for comment only after we were satisfied that his work was well done. . . The Quarterly boasts that all in America is not jazz, noise and fury; a minority speaks vigorously and clearly, with intelligence, understanding, humor and craftsmanship. Ralph’s essay helps prove this assertion. Read young Oppenheim’s study and you will realize how important it is for the United States to have a magazine the purpose of which will be to go out and seek for the best from the talented and intelligent minority, bringing out new gifts, fresh viewpoints and sound work. First credit must, of necessity, go to Ralph himself; second credit must go to his artist-mother, Gertrude Oppenheim, and his poet father, James Oppenheim; third credit, in all fairness, must go to the Quarterly for opening its columns to a new voice. America will hear much from Ralph Oppenheim. He has something to say; he knows how to say it; he is a civilized human being, a complete answer to the charge that all of America has been reduced to stifling mediocrity, to unimaginative standardization. There is enough to complain about, in all truth, without crying that all is lost. Let us protest against the viciousness and stupidity of the superstitious majority, the hypocrisy and cowardice of its leaders, the mawkishness of our bunk-ridden millions—yes, let us aim our spitballs at our shams and fakirs, but let us, by all means, recognize worthy talent when we see it and lend an ear to the emerging youngsters who are breaking away from the herd and learning to stand as free individuals. Turn now to Ralph’s essay. At first you will marvel that it was written by a boy, but after a few paragraphs you will forget its author and fly along with his tonic and captivating work. . . . The portrait of George Sand was drawn especially for the Quarterly by Mrs. James Oppenheim, Ralph’s mother. The second issue of the Haldeman-Julius Quarterly (January 1927) featured Oppenheim’s “The Romance That Balzac Lived: How The Great Interpreter of the Human Comedy Lived and Loved” (a reprinting of The Romance That Balzac Lived: Honore de Balzac and the Women He Loved (lbb-1213, 1927)). The article was nicely illustrated with a daguerreotype of Balzac and spot illustrations by Fred C. Rodewald, but no introductory page about Oppenheim.

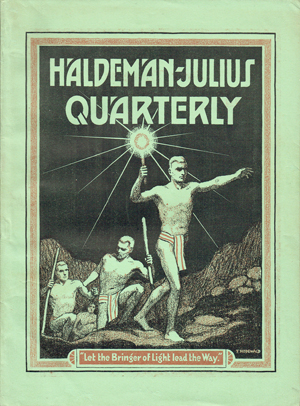

The second issue of the Haldeman-Julius Quarterly (January 1927) featured Oppenheim’s “The Romance That Balzac Lived: How The Great Interpreter of the Human Comedy Lived and Loved” (a reprinting of The Romance That Balzac Lived: Honore de Balzac and the Women He Loved (lbb-1213, 1927)). The article was nicely illustrated with a daguerreotype of Balzac and spot illustrations by Fred C. Rodewald, but no introductory page about Oppenheim. Oppenheim seemed to be a role with the Haldeman-Julius Quarterly readers (or at least their editors), for the third issue (April 1927) once again featured an article by Oppenheim. This time it was his treatise on his generation: “The Younger Generation Speaks: An American Youth Tells About Its Attitude Toward Life” (a reprinting of

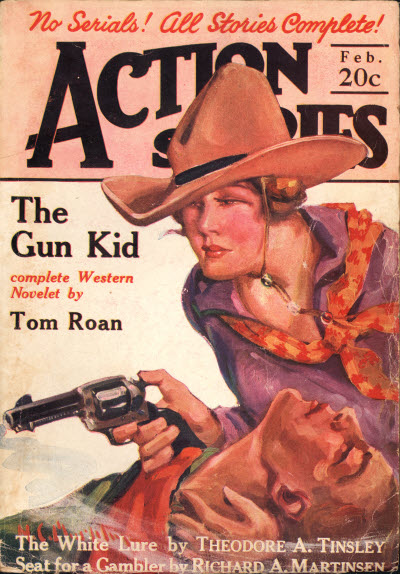

Oppenheim seemed to be a role with the Haldeman-Julius Quarterly readers (or at least their editors), for the third issue (April 1927) once again featured an article by Oppenheim. This time it was his treatise on his generation: “The Younger Generation Speaks: An American Youth Tells About Its Attitude Toward Life” (a reprinting of  His first published story was a taunt tale of aviation and death he titled “Doom’s Pilot” in the pages of the February 1927 Action Stories! His second printed story—”A Parachutin’ Fool”—was another aviation tale, printed in the April 1927 issue of War Stories! He followed this up with—”Aces Down!”—in the July 1927 issue of War Stories—this was the story that introduced the world to that inseparable trio—The Three Mosquitoes!

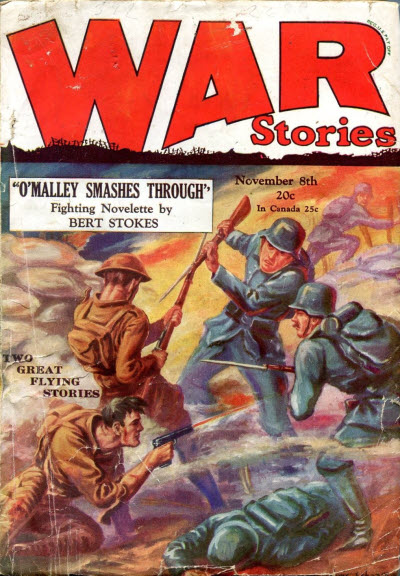

His first published story was a taunt tale of aviation and death he titled “Doom’s Pilot” in the pages of the February 1927 Action Stories! His second printed story—”A Parachutin’ Fool”—was another aviation tale, printed in the April 1927 issue of War Stories! He followed this up with—”Aces Down!”—in the July 1927 issue of War Stories—this was the story that introduced the world to that inseparable trio—The Three Mosquitoes! the third and final of three Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes stories we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! And this one’s a doozy! The Boche have some new super-gun that has been ranging the Allied munitions factory, getting closer every time. Kirby, Carn and Travis are tasked with finding the unfindable gun and putting it out of commission before it does indeed hit the munitions factory! It’s another rip-roaring nail-biter from the pages of the November 8th, 1928 issue of War Stories—The Three Mosquitoes must “Get That Gun!”

the third and final of three Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes stories we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! And this one’s a doozy! The Boche have some new super-gun that has been ranging the Allied munitions factory, getting closer every time. Kirby, Carn and Travis are tasked with finding the unfindable gun and putting it out of commission before it does indeed hit the munitions factory! It’s another rip-roaring nail-biter from the pages of the November 8th, 1928 issue of War Stories—The Three Mosquitoes must “Get That Gun!”

the second of three tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, Kirby experiences the pitfalls of pride when the Boche form an All-Ace squadron called the Avenging Yellow Jackets to take down the pesky Mosquitoes—while Shorty Carn and the lanky Travis urge caution, Kirby’s all guns ahead ready to rush in and take on all the Aces Germany can dish out. Problem is, believing his own press, he rushes into things foolishly and finds himself in “Hot Air!” From the February 2nd, 1928 issue of War Stories—

the second of three tales of Ralph Oppenheim’s Three Mosquitoes we’re featuring this March for Mosquito Month! This week, Kirby experiences the pitfalls of pride when the Boche form an All-Ace squadron called the Avenging Yellow Jackets to take down the pesky Mosquitoes—while Shorty Carn and the lanky Travis urge caution, Kirby’s all guns ahead ready to rush in and take on all the Aces Germany can dish out. Problem is, believing his own press, he rushes into things foolishly and finds himself in “Hot Air!” From the February 2nd, 1928 issue of War Stories—

off the ground with an early Mosquitoes tale from the pages of the August 19th, 1927 issue of War Stories. A new C.O. has been assigned to the squadron and he can’t stand pilots who “grand-stand” which is the Mosquitoes stock-in-trade and boy do they catch hell when they get on the C.O.’s wrong side—that is until the C.O. gets in a jam and it’s trick flying that’ll save him when the Boche come “Down from the Clouds!”

off the ground with an early Mosquitoes tale from the pages of the August 19th, 1927 issue of War Stories. A new C.O. has been assigned to the squadron and he can’t stand pilots who “grand-stand” which is the Mosquitoes stock-in-trade and boy do they catch hell when they get on the C.O.’s wrong side—that is until the C.O. gets in a jam and it’s trick flying that’ll save him when the Boche come “Down from the Clouds!”