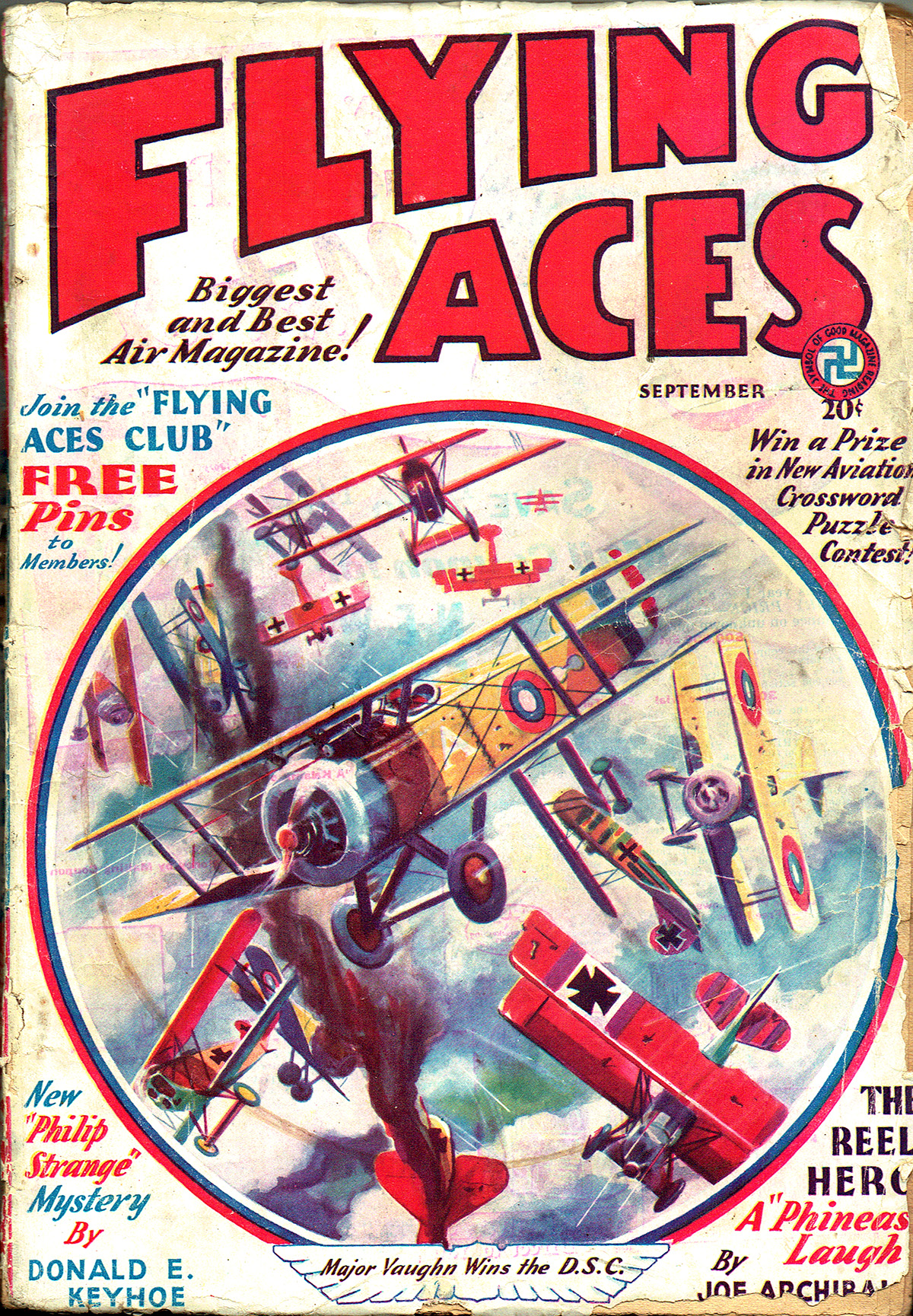

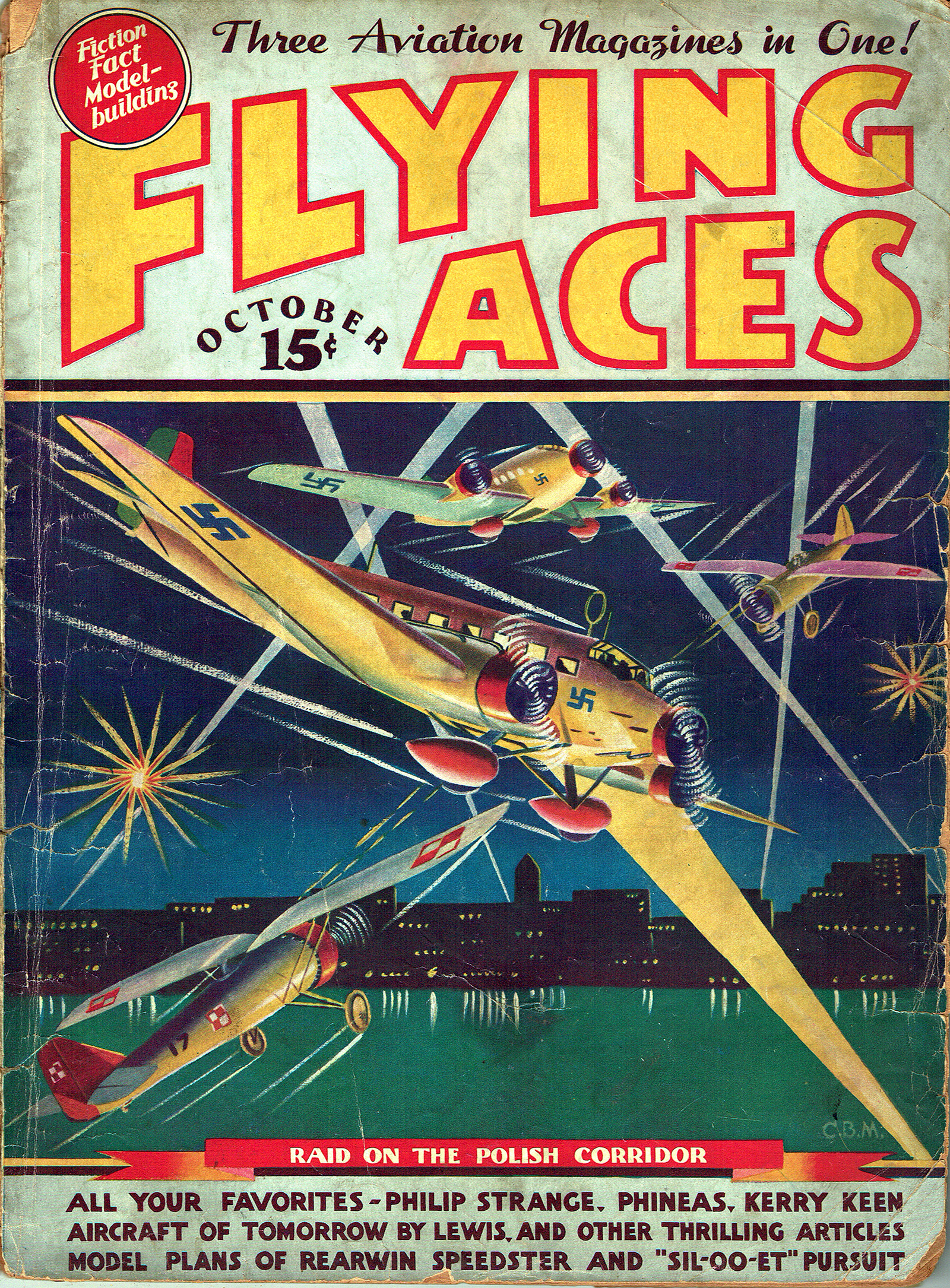

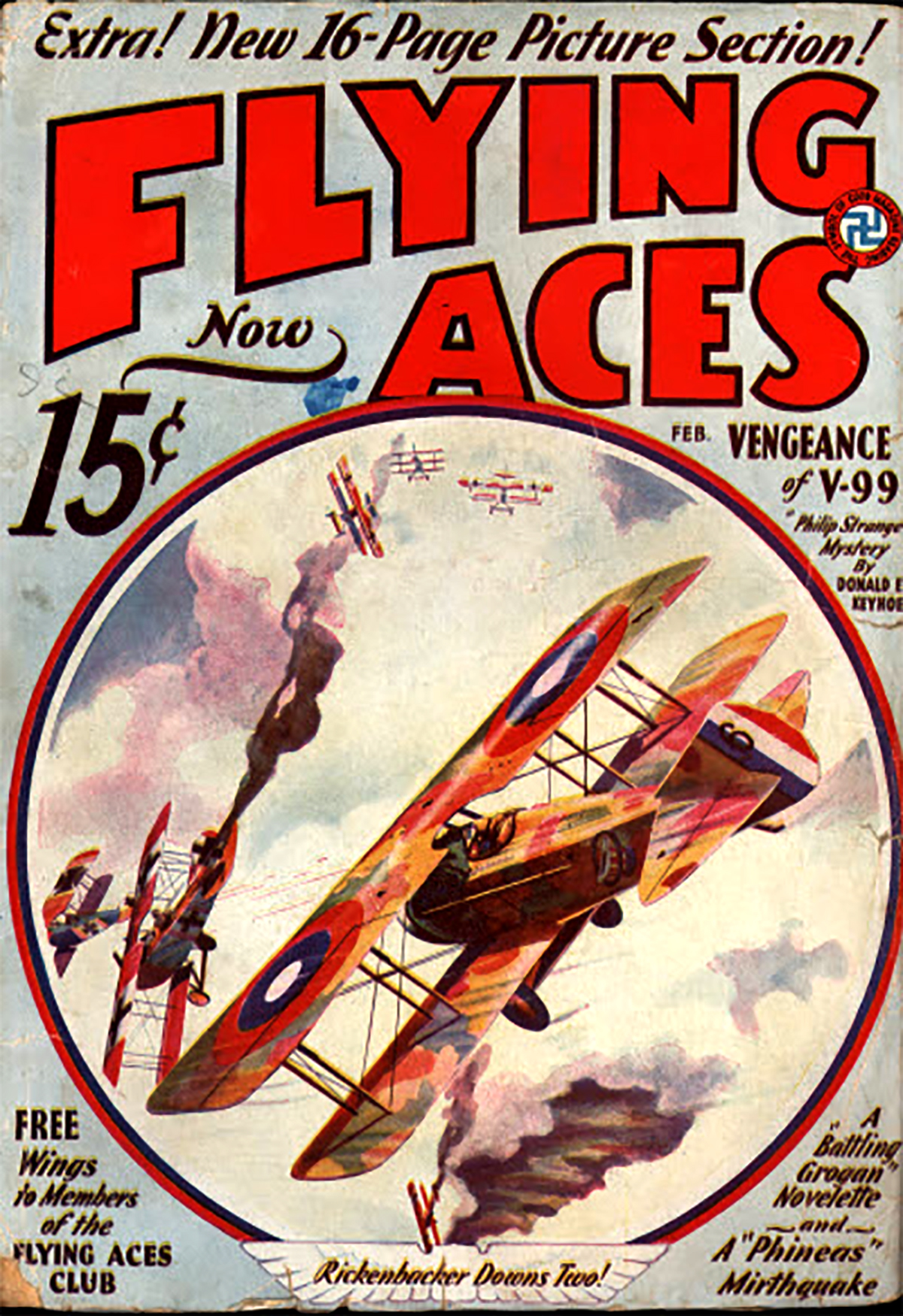

THIS week we present another of Paul Bissell’s covers for Flying Aces! Bissell is mainly known for doing the covers of Flying Aces from 1931 through 1934 when C.B. Mayshark took over duties. For the October 1932 cover Bissell put us right in the action as Rhys-Davids downs Werner Voss!

War’s Youngest Ace Downs Voss

YOUTH, winged youth. Youth, flying to meet death.

YOUTH, winged youth. Youth, flying to meet death.

In all the strange chapters that came from the war there is nothing more incredible than the youthfulness of its air heroes.

23 years old—a major. Officially credited with seventy-five victories in individual combat.

22 years old—a captain. Internationally known for aggressive bravery, the idol of his nation, and a price on his head, dead or alive.

21 years old—a lieutenant. With more than twoscore victories to his credit. Decorated by nations and feted by kings.

And so it went, on down—20 years—19 years—18 years—and there it stops—officially! But listen:

“And you,†said the recruiting sergeant to a glad-faced youngster who stood, bright-eyed, in front of him. “What do you wish?â€

“I’ve come to enlist, sir,†replied the boy.

“Enlist, is it? And do you think it’s a kindergarten in France we be asending the lads to?â€

“No, sir. I mean to fight,†was the quiet answer.

For an instant the sergeant studied the serious eyes before him. “And your age, my boy?â€

“Fift—I mean eighteen, sir.â€

“Eighteen, eh,†growled the sergeant, shaking his head as he reached for an enlistment blank. “Do you know what you’re doing, sonny?â€

“Righto, sir.â€

“Righto, it is then. And eighteen years ye be, though if you’re eighteen, Mister Methusaleh is my name. What’s your name, youngster?â€

“Rhys-Davids, sir,†he replied, and a school lad had started on the road to glory, death and fame.

It was early autumn of seventeen, and the 56th Squadron, R.F.C., was in the thick of it. This famous squadron almost daily battled Richthofen and the best of his “gentlemen.†Fought them through the entire war to a credit of 411 planes downed—but not without themselves adding many famous names to the already long list of those who died for England. Included in this list was the name of their famous commander, McCudden, with fifty-eight victories to his personal credit.

Here, with this outfit, was the lad who had come to France “meaning to fight.†And fight he had. Never was there a pilot more willing or eager for a scrap. He would attack recklessly, even though outnumbered, and in a dogfight he became a madman—a madman dealing death to the enemy. And then he would return to his drome to become all boy again. A happy boy, with pets—birds that sang to him—pups that “Waited each day for his return—and tame rabbits that nipped off the shoots in the little garden behind his shack and nibbled greens, from his hand.

Already more than a score of German. had fallen before his fire. Schaffer, of “Richthofen’s Own,†had fought his last fight against this youngster. But it was on September 23, 1917, that he gained his most famous victory.

THE squadron was on patrol, protecting some bombers, when off to one side were seen two German planes. It did not seem likely that they would attack, as the English squadron numbered more than a dozen of Bristols, Camels and S.E.Ss. That is, it did not seem likely until, by the black-and-white-checkered fuselage it was seen that one of the Germans was Lieutenant Werner Voss.

This was one adversary that the Allies held in the greatest respect. Already both his plane and name were known all up and down the Front. He was always looking for combats, and fought generally over Allied territory, which could not be said of Richthofen. And with forty-eight victories over the Allies, Voss, himself of most humble origin, was a serious rival of the noble-born baron.

Indeed, records seem to show that Voss, feeling himself in every way the equal of his rival as an ace, had refused to be the tail protector to Richthofen and, on at least one occasion, when the victories of Voss had reached a number almost equal to those of the Rittmeister himself, the High Command had seen fit to transfer the mere “Lieutenant†to a less active sector, where opportunities for combat were fewer.

With such an opponent as this, the Britishers knew that attack might be expected, and when, a moment later, a patrol of Albatrosses appeared, no one was surprised to see the checkered triplane dive in headlong. Voss’ companion, flying to one side and slightly behind, was almost immediately shot down. And when the Albatrosses refused to accept battle, Voss was left to his fate.

It was an unequal fight, though after the German had winged his way through the first terrific rain of fire from all the other ships, it was Rhys-Davids who engaged him in a duel. Around and around they tore, with Voss, hemmed in on all sides, hoping only to sell his life as dearly as possible. The Fokker tripe, with its German pilot, had met its equal in the little S.E.5 flown by the English boy!

The British plane turned and twisted, meeting maneuver with maneuver, until at last the looked-for opening came and the checkered fuselage for a moment was full in the sights. Just for an instant—but an instant that was filled with spitting lead, an instant that began that mad, twisting dive that ended near Poelcapelle for the triplane with the black crosses on its wings, and ended in eternity for the brave German ace.

Rhys-Davids followed him down to the ground. It was the game—there must be no slip. Then, with motor full on, himself untouched, he raced back to his pets.

The lad—his comrades thought he must be now almost seventeen years old—had thirty-two unofficial victories to his credit, and those gods that be must have laughed as they wrote his name on a shell. No German airman carried it. But an Archie battery, a month later, shot it from the ground. Ten thousand feet up it found him.

Back in his shack the birds still sang in their cages and the rabbits still nibbled in the garden. But the puppies waited the return of their boy master in vain, for the war’s youngest ace had gone West.

“War’s Youngest Ace Downs Vossâ€

Flying Aces, October 1932 by Paul J. Bissell

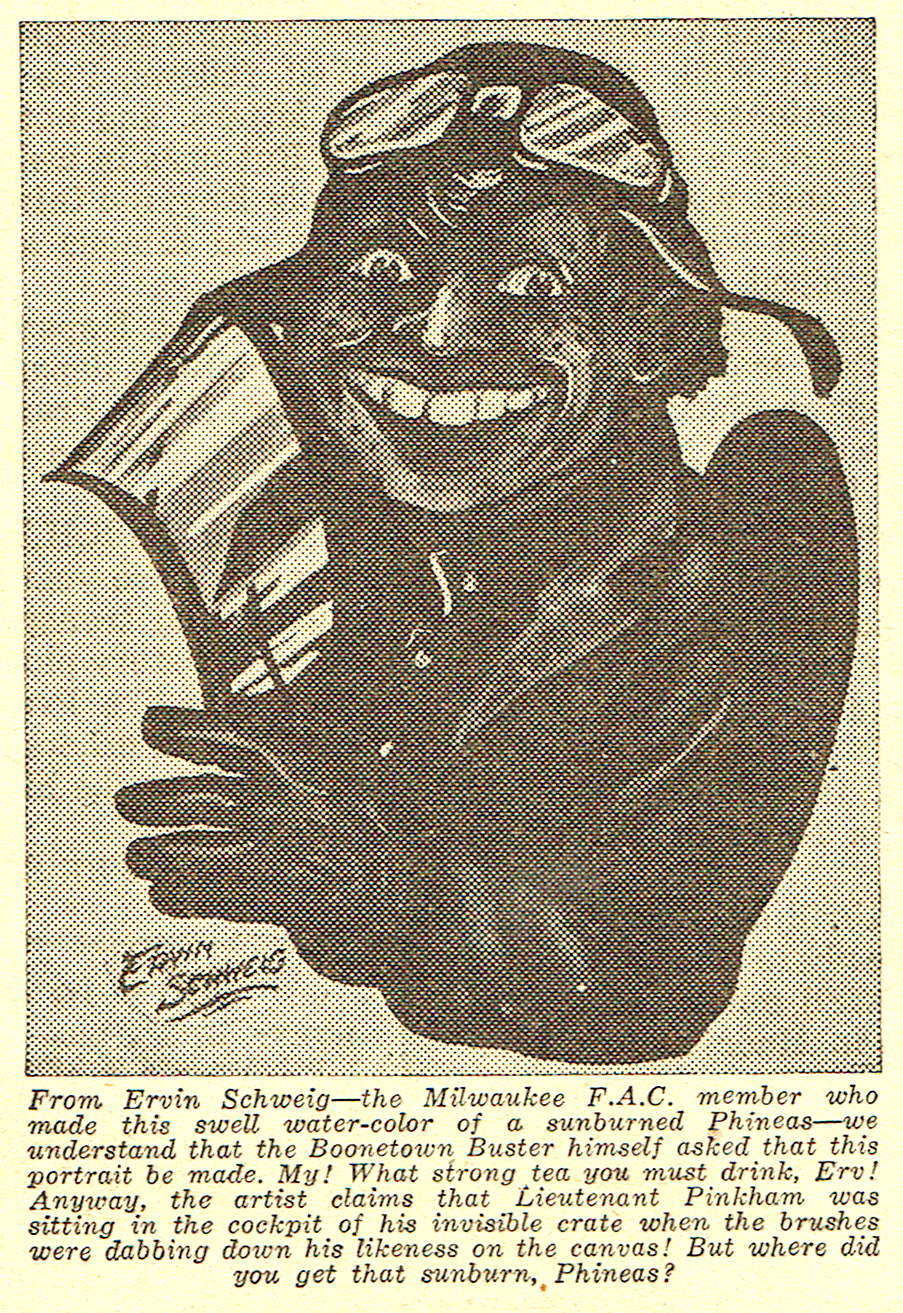

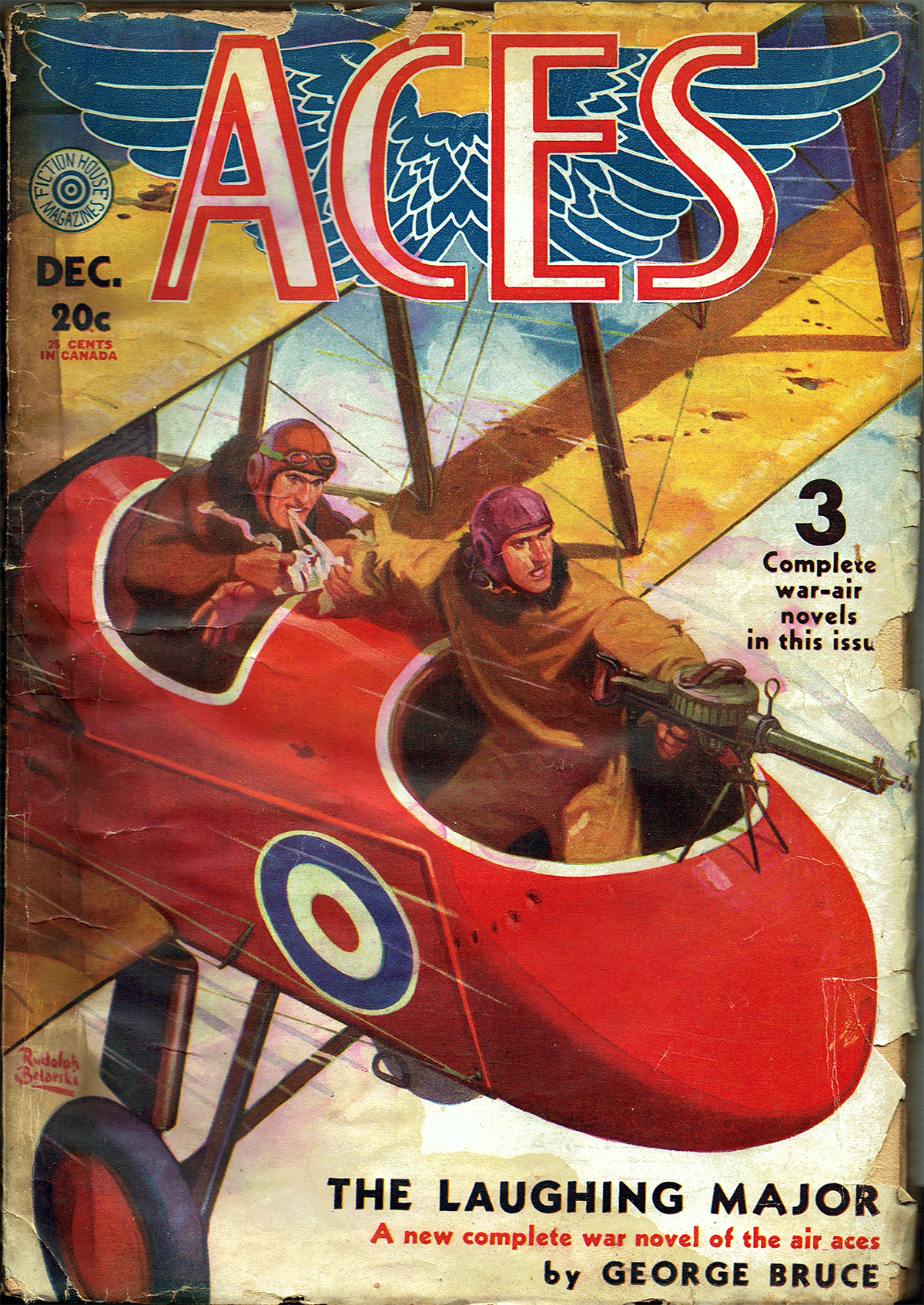

one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

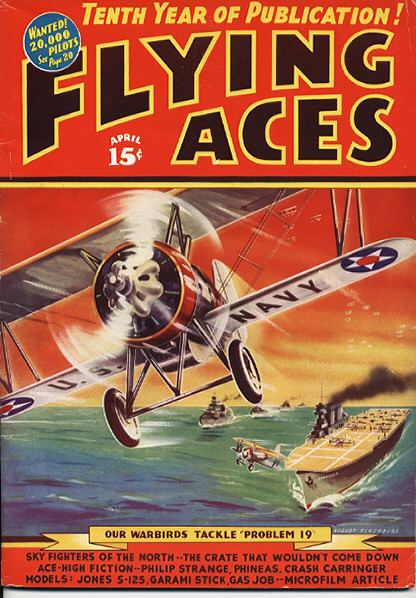

and there’s no bigger April fool than that Bachelor of Artifice, the Knight of Calamity, an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham, the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa!

and there’s no bigger April fool than that Bachelor of Artifice, the Knight of Calamity, an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham, the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!

That sound can only mean one thing—that Bachelor of Artifice, Knight of Calamity and an alumnus of Doctor Merlin’s Camelot College for Conjurors is back to vex not only the Germans, but the Americans—the Ninth Pursuit Squadron in particular—as well. Yes it’s the marvel from Boonetown, Iowa himself—Lieutenant Phineas Pinkham!