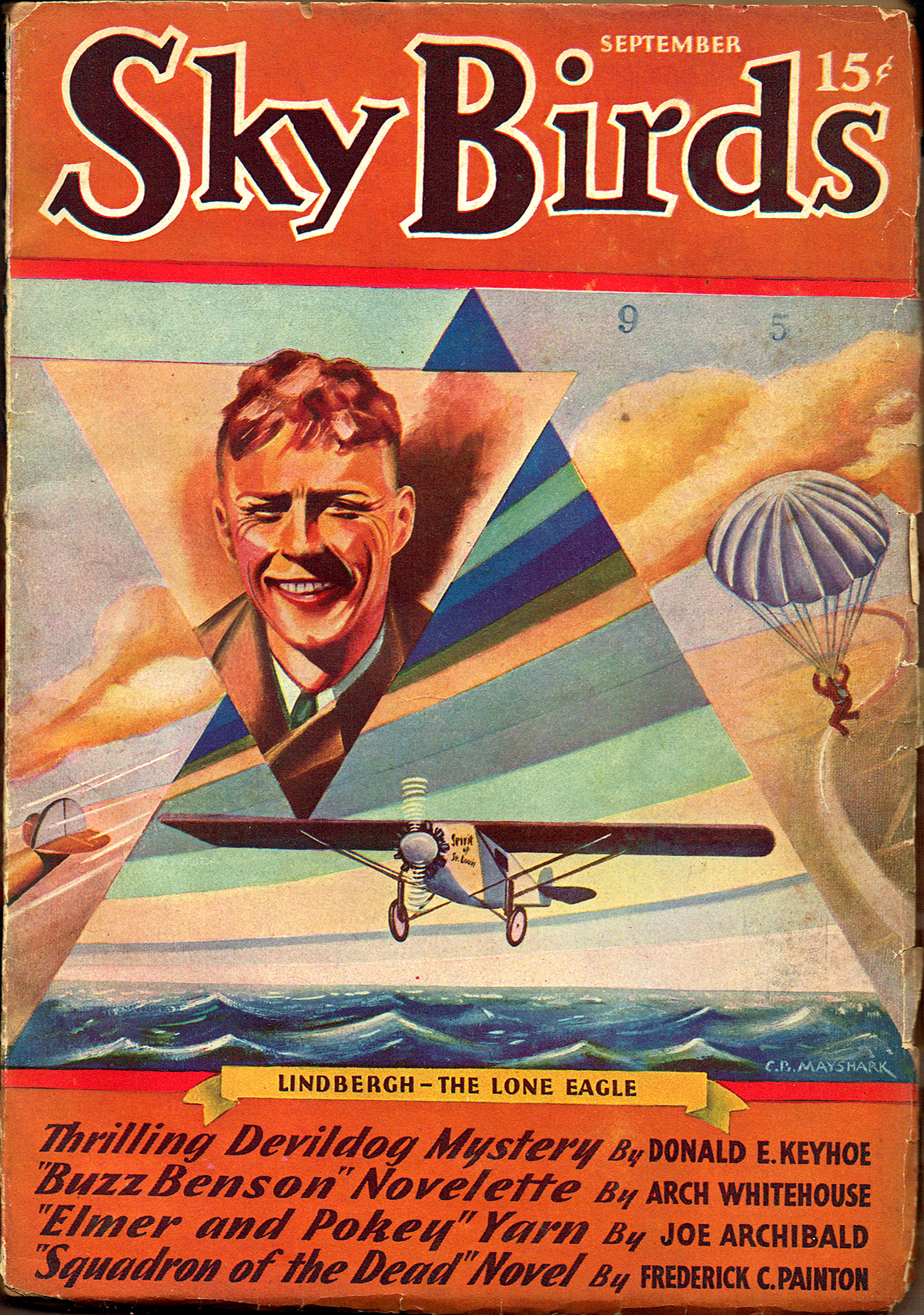

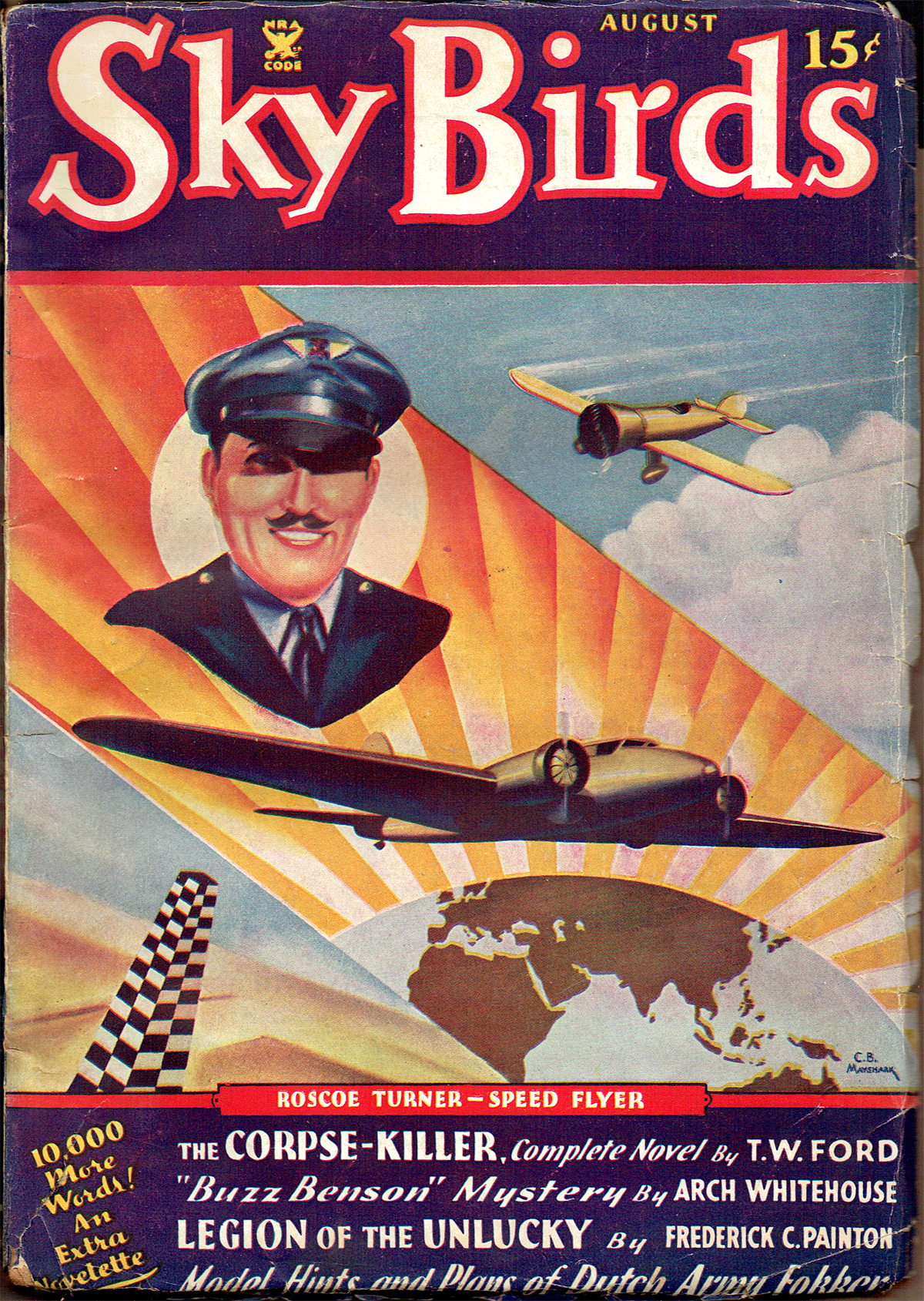

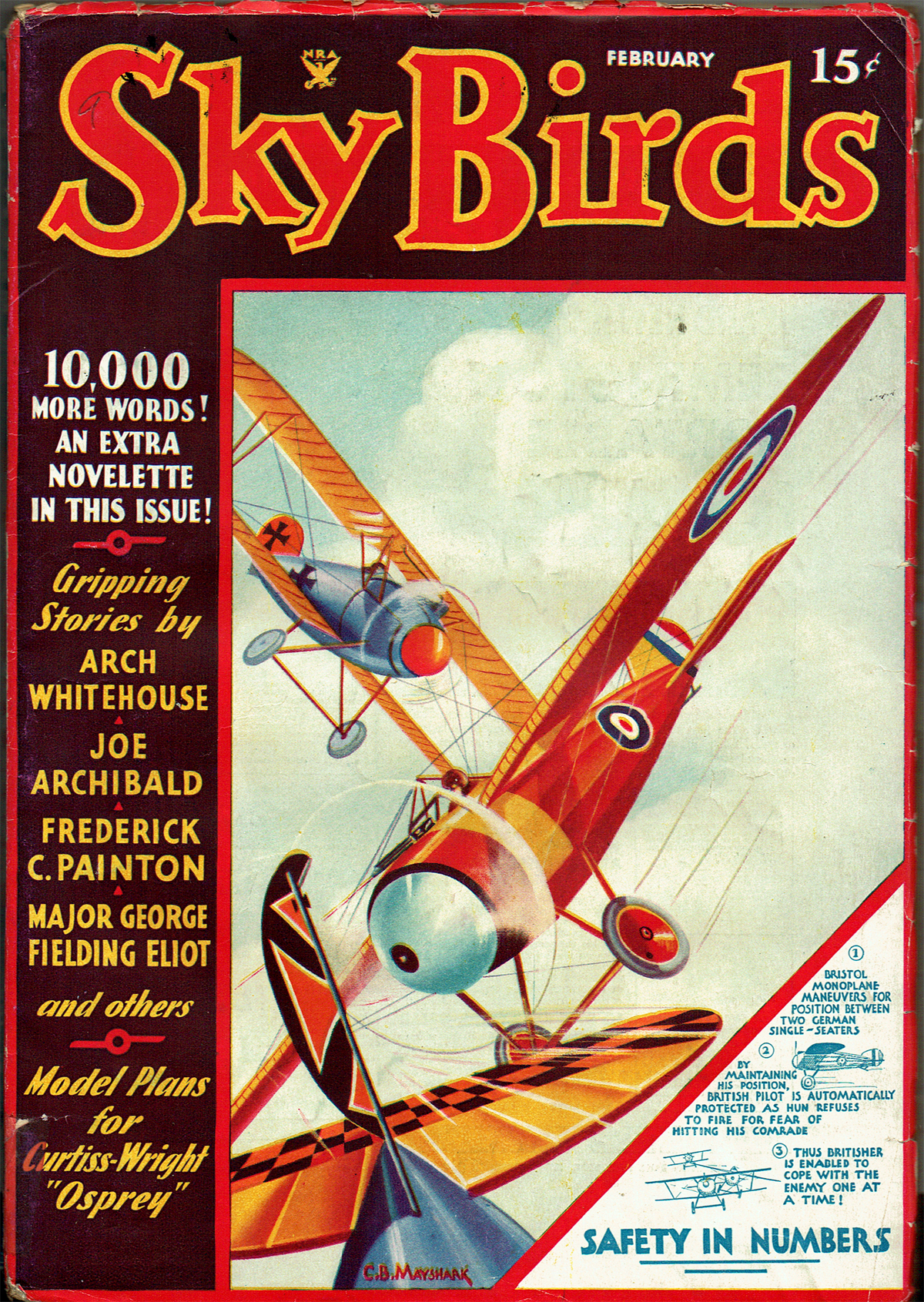

“Wiley Post: Ace of World-Girdlers” C.B. Mayshark

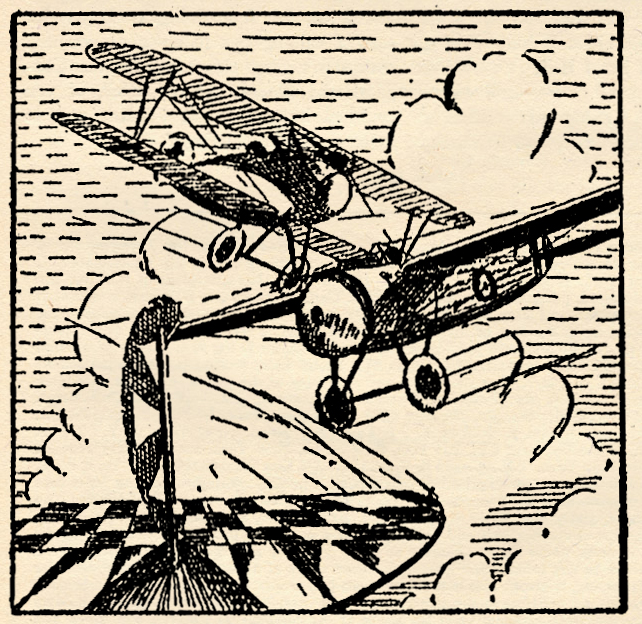

THIS May we are once again celebrating the genius that is C.B. Mayshark! Mayshark took over the covers duties for Sky Birds with the July 1934 and would paint all the remaining covers until it’s last issue in December 1935. At the start of his run, Sky Birds started featuring a different combat maneuver of the war-time pilots. Mayshaerk changed things up for the final four covers. Sky Birds last four covers each featured a different aviation legend. Wiley Post is the subject of Mayshark and Sky Bird’s final cover in December 1935!

Wiley Post: Ace of World-Girdlers

The Story Behind This Month’s Cover

A MAN who rose from the depths of obscurity and poverty to world fame—a man whose iron courage and unwavering determination carried him to an undreamed of position in the spotlight of human interest—a man who conquered a physical handicap which undoubtedly would have quickly curbed others—but most of all a man who had true unflinching fortitude—a man who had what it takes! Such a man was Wiley Post, who was killed instantly with Will Rogers in a crash in the wilds of

Alaska a few miles south of Point Barrow, on August 16.

A MAN who rose from the depths of obscurity and poverty to world fame—a man whose iron courage and unwavering determination carried him to an undreamed of position in the spotlight of human interest—a man who conquered a physical handicap which undoubtedly would have quickly curbed others—but most of all a man who had true unflinching fortitude—a man who had what it takes! Such a man was Wiley Post, who was killed instantly with Will Rogers in a crash in the wilds of

Alaska a few miles south of Point Barrow, on August 16.

Wiley was the type of fellow who believed unreservedly in himself. In his youth he was a worker in the oil fields of the West. He got his first taste for the air when a barnstorming pilot who was passing through town took him up for a spin for a fee of $25. It was money well spent, for Wiley quickly decided to become a pilot himself.

But at this point all his ambitions seemed doomed even before they had begun to be realized. An accident in the oil fields rendered Post’s left eye sightless, and it had to be removed. At first he despaired of ever becoming an airman; but upon application for flying lessons, he discovered that what he wanted to do was not impossible. All be needed was determination—and he had plenty of that! He passed his examination in short order, and with the compensation he received for his injury in the oil fields be bought his first plane—an antiquated “Jenny.”

From that time on, Wiley’s future was entirely in his own hands. Whatever he decided to do, he did without hesitation. Every activity in which he engaged added to the vast experience and knowledge which he finally brought to bear in his first record breaking flight around the world with Harold Gatty.

With that flight, Post first won worldwide acclaim. He and Gatty were accorded a royal reception when they landed back in New York on July 1, 1931 after circling the earth in 8 days, 15 hours, and 51 minutes. They bad accomplished one of the most difficult feats ever attempted in the history of aviation.

Post was destined to soar on to even greater heights. From June 23 to June 30, 1933, he covered, with the aid of a robot pilot, the same round-the-world course solo in the new time of 7 days, 8 hours and 49½ minutes.

By this time, the name of his ship, the “Winnie Mae,” was on the lips of the whole world. But Wiley didn’t get a swelled head. Instead, he again plugged on. He still had his eye on the future—living on his laurels was something he couldn’t do. “Accomplishment” was his slogan.

Between February 22 and June I5, 1935, Post made four attempts to span the continent in the sub-stratosphere. Four times he was forced to land his ship short of its mark. All the attempts were failures. But Wiley undoubtedly would have carried on to success had his life not been snatched from him. We picture him in his stratosphere suit.

THE memory of this great airman will live on in the hearts of mankind, for he was the type of individual whom every man wishes to emulate.

Following the news of Post’s death, the United States Senate passed a resolution which authorized the purchase, for $25,000, of Wiley’s plane, the “Winnie Mae,” for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington! And so, the ship which carried Wiley Post to the heights of human accomplishment will be preserved for posterity. Something material, however, is not required to keep the memory of Wiley with us. He shall live on in spirit forever.

“Wiley Post: Ace of World-Girdlers” by C.B. Mayshark

Sky Birds, December 1935