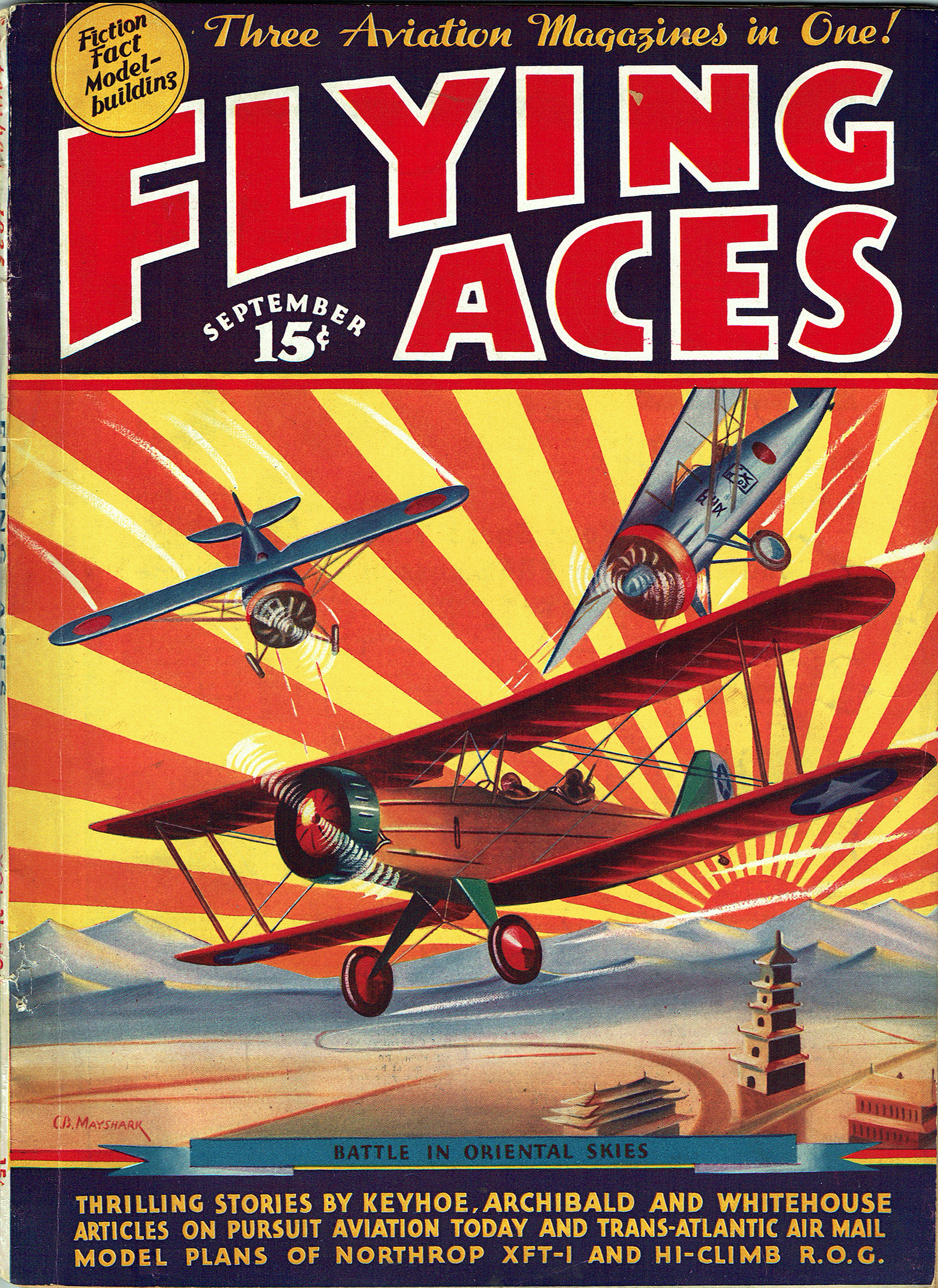

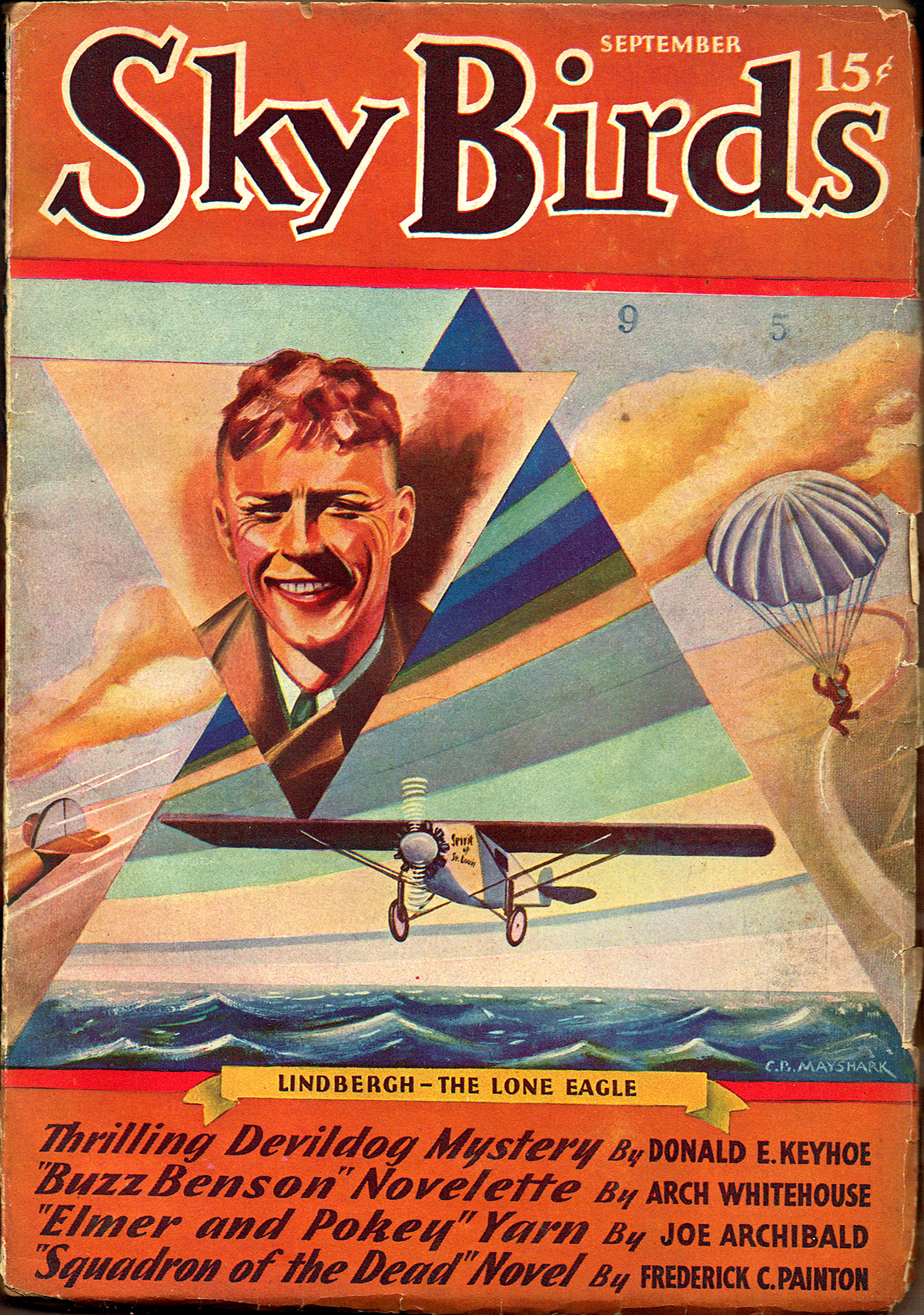

“Flying Aces, September 1935″ by C.B. Mayshark

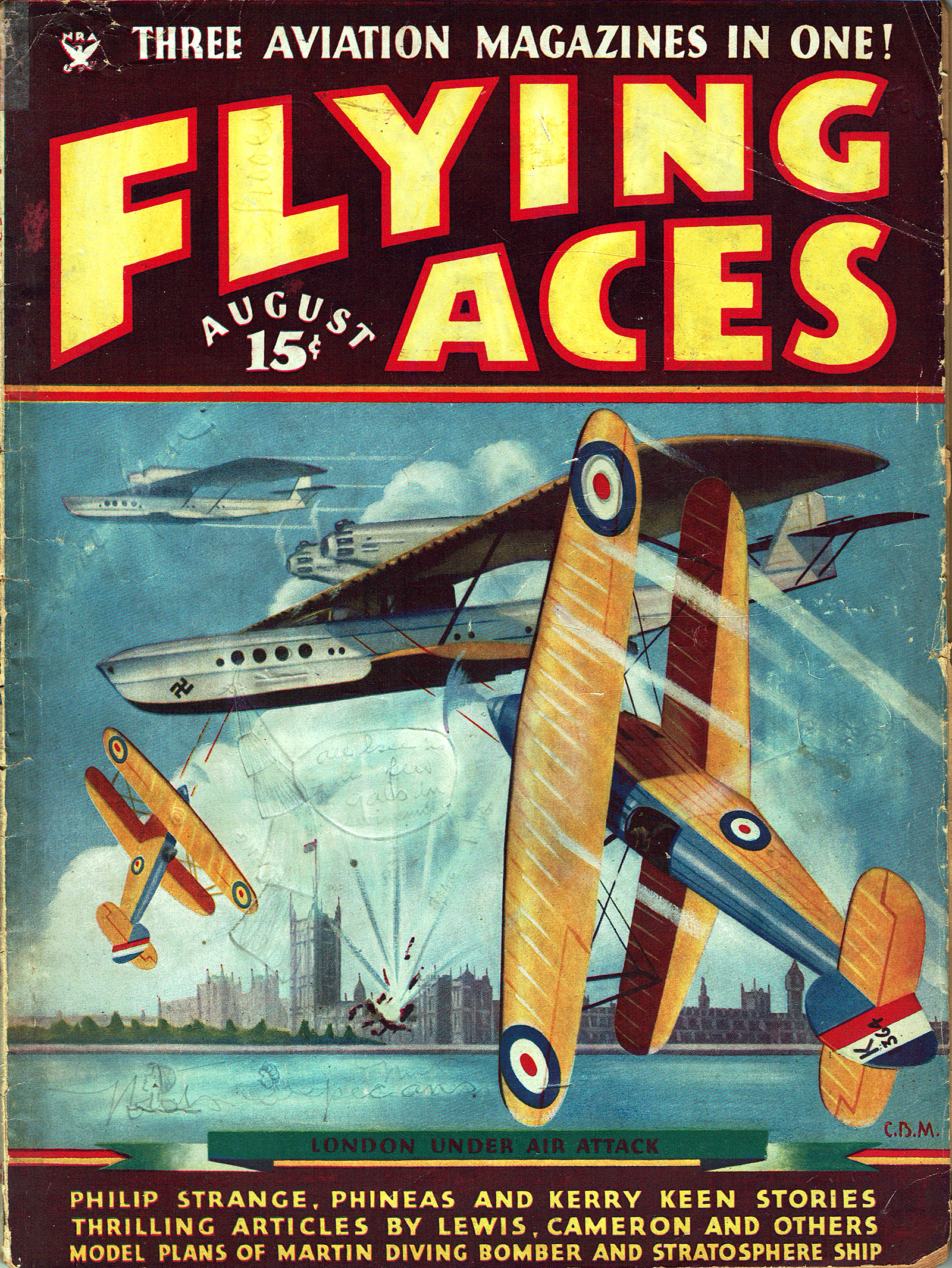

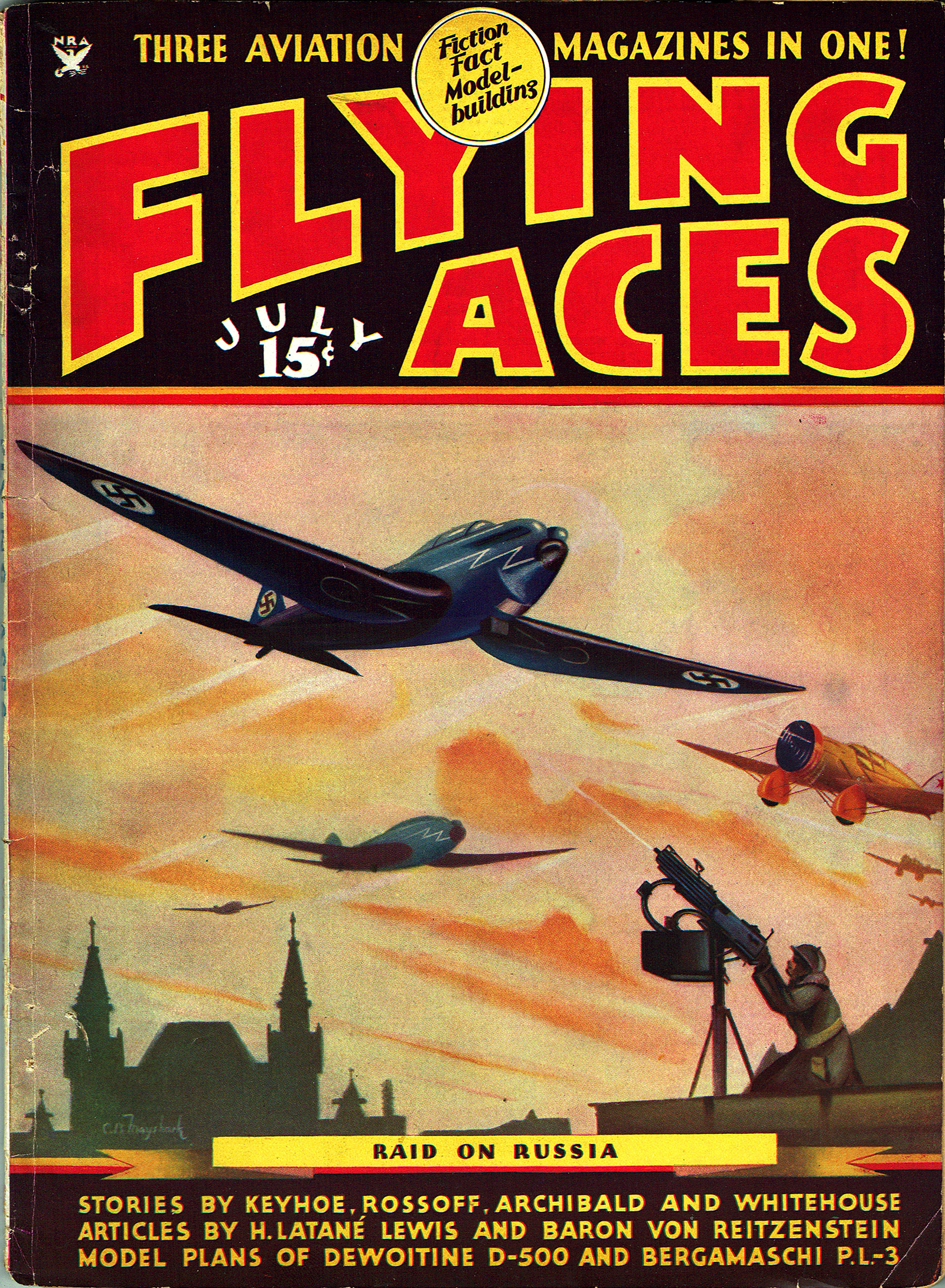

THIS May we are once again celebrating the genius that is C.B. Mayshark! Mayshark took over the covers duties on Flying Aces from Paul Bissell with the December 1934 issue and would continue to provide covers for the next year and a half until the June 1936 issue. While Bissell’s covers were frequently depictions of great moments in combat aviation from the Great War, Mayshark’s covers were often depictions of future aviation battles and planes—like the September 1935 cover where Mayshark gives us a glimpse of an air Battle in Oriental Skies!

Battle in Oriental Skies

THE drowning of powerful motors, the rattle of machine-gun fire, the shrieking of a ship falling out of control, the gasp of horror coming from the civil population—it means but one thing—the Japanese have struck!

THE drowning of powerful motors, the rattle of machine-gun fire, the shrieking of a ship falling out of control, the gasp of horror coming from the civil population—it means but one thing—the Japanese have struck!

And when the Japanese strike, it is like the lightning thrust of the hooded cobra. It is sudden and effective, and over almost as soon as it has begun. The resistance of the Chinese border patrols is determined, however, even if it is of little value against the power and speed of the machines from the land of the rising sun.

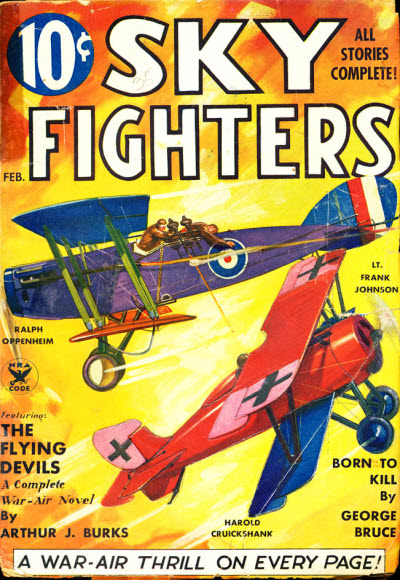

On our cover this month, we have depicted for you a clash between a Chinese-owned Douglas and a Japanese-built Nakajima. The territory over which the battle takes place is near a border in the hill country in North China. The approach of the single-seaters has been telegraphed ahead, and a Douglas two-seater takes the air in an effort to defend the district from the raking enemy machine-gun fire and from the destructive bombers which must surely follow the Nakajimas.

Ironically enough, the Douglas comes up with the two Japanese single-seaters directly above a temple of worship, many of which are to be found in isolated regions in North China. As the Japanese pilots spot the Douglas, they realize that their task is a comparatively simple one. The two-seater would not have any real effectiveness against the powerful bombers which are to come, but nevertheless, a pile of smouldering debris on the ground is of more benefit to the Japanese at this particular point than an unchecked stream of lead spattering its message of death at them, even, if it is coming from a Douglas 02MC4.

And so the machines from across the water set upon the Chinese with a vengeance. Attacking in unison, they bear down on the Douglas with several hundred feet of altitude to their advantage. As they approach their target, they spread out fan-wise, and then bank sharply in toward each other so that the line of fire from both ships converges at the unhappy point at which the Douglas finds itself.

However, the Chinese pilot has participated in air defense maneuvers before, and he knows what tactics are required to beat off these vicious Nakajimas. However, he knows how hopeless it is to count on getting even one of these Japanese boys, much less both. Of course, being a good pilot, he can cut his gun and nose his ship sharply up, and so escape the first death-dealing crossfire, but the ultimate outcome is written in blood on every burst of Japanese tracer which comes tearing down the sky.

The result of the fight is so obvious that further elaboration is unnecessary. Of course, the Japanese take the territory, as the resistance is nil after the first onslaught. But another blow has been struck, and the Chinese pride has suffered once more.

With the advent of modern aerial warfare, the Sino-Japanese situation has taken on an entirely different aspect. Border raids by foot soldiers have almost become a thing of the past, and in their stead, swift powerful attacks from the air are the signal for a belligerent and highly mechanized maneuver.

A thing of great importance is the moral effect of bomb-dropping on the Chinese civil population. On the ignorant superstitious hillman, this effect is far greater than it ever could be on any nation of people in the Western hemisphere. The Chinese are, as a general rule, conscious of their vast strength and wealth, and they naturally assume that they can successfully wage war with Japan. The confusion that results from the petty ambitions of the individual war lords, however, complicates matters to such an extent that unified resistance against Japan seems out of the question.

In spite of all this, the Central Government has made an effort to defend itself against the air attacks of the invader. Lacking the modern industrial activity with which the Western world is blessed, the Chinese are compelled to buy their machines of war, if they are to have any, outside their own country. American airplane manufacturers have been favored with much of this lucrative business.

The lack of centralization of the Chinese military activity is evidenced by the fact that the air forces of the various provinces are independent of each other, although a friendly relationship exists between the larger provinces in most instances. The provinces of Canton, Kwangsi, and Fukien, among others, have independent air forces.

In direct contrast, the Japanese do much of their own manufacturing. They have acquired the industrial fever with which the West is imbued.

As has been said, the Chinese ship on our cover is an American-built Douglas 02MC4. Several Douglas ships have been purchased by China, as well as many other types, including Vought and Waco. Types other than American include Junkers, Fiats, De Havillands, and Armstrong-Whitworths.

And here’s an interesting point. To close followers of military aviation design, the Nakajima monoplane fighter seems very similar to the Boeing single-seater developed in this country three years ago. Inspection will show that the unusual strutting arrangement displayed on the Japanese ship is exactly like that of the Boeing which came out under the type numbers 270-V. The fuselage was smooth monocoque; the motor is mounted in the same way and the same type of undercarriage is used. The only improvement the Japanese added was the Townsend ring around the engine.

In other words, there might be such a thing as espionage in aviation after all!

Flying Aces, September 1935 by C.B. Mayshark

Battle in Oriental Skies: Thrilling Story Behind This Month’s Cover

a story by another of our favorite authors—

a story by another of our favorite authors—

the City of New York on November 16, 1900. It was snowing like blazes that day, if I remember rightly. Anyway, 1 managed to survive the hazards of Manhattan boyhood until I was sixteen, then, while the native New Yorkers of my age were pouring in from Kansas, Missouri and Minnesota, I followed the family star of destiny to Colorado. I had prepared at Manhattan College Prep in New York for an engineering career, but this proved to be a misdeal and I took a whirl at reporting for a Denver daily. I never progressed past the cub stage and was fervently advised by a harassed city ed. that I never would. After that I became one of the young men who signed the coupon.

the City of New York on November 16, 1900. It was snowing like blazes that day, if I remember rightly. Anyway, 1 managed to survive the hazards of Manhattan boyhood until I was sixteen, then, while the native New Yorkers of my age were pouring in from Kansas, Missouri and Minnesota, I followed the family star of destiny to Colorado. I had prepared at Manhattan College Prep in New York for an engineering career, but this proved to be a misdeal and I took a whirl at reporting for a Denver daily. I never progressed past the cub stage and was fervently advised by a harassed city ed. that I never would. After that I became one of the young men who signed the coupon. Great thinkers are not lions for courage—thought convinces them of the folly of risk. I am thinking of the men who brought the law to the wilderness in the first place (the same type who will bring it back when it strays). Most of them were men who sought escape from the law some place else— not sticklers for the fine points of the written law, but foursquare for a square deal and for the rights of human beings to live their lives and keep what they have. Derek Dane stands for that and, if he steps outside the statute book to get results, he has fundamental laws to justify him.

Great thinkers are not lions for courage—thought convinces them of the folly of risk. I am thinking of the men who brought the law to the wilderness in the first place (the same type who will bring it back when it strays). Most of them were men who sought escape from the law some place else— not sticklers for the fine points of the written law, but foursquare for a square deal and for the rights of human beings to live their lives and keep what they have. Derek Dane stands for that and, if he steps outside the statute book to get results, he has fundamental laws to justify him.

Silent Orth had made an enviable record, in the face of one of the worst beginnings—a beginning which had been so filled with boasting that his wingmates hadn’t been able to stand it. But Orth hadn’t thought of all his talk as boasting, because he had invariably made good on it. However, someone had brought home to him the fact that brave, efficient men were usually modest and really silent, and he had shut his mouth like a trap from that moment on.

Silent Orth had made an enviable record, in the face of one of the worst beginnings—a beginning which had been so filled with boasting that his wingmates hadn’t been able to stand it. But Orth hadn’t thought of all his talk as boasting, because he had invariably made good on it. However, someone had brought home to him the fact that brave, efficient men were usually modest and really silent, and he had shut his mouth like a trap from that moment on. Silent Orth had made an enviable record, in the face of one of the worst beginnings—a beginning which had been so filled with boasting that his wingmates hadn’t been able to stand it. But Orth hadn’t thought of all his talk as boasting, because he had invariably made good on it. However, someone had brought home to him the fact that brave, efficient men were usually modest and really silent, and he had shut his mouth like a trap from that moment on.

Silent Orth had made an enviable record, in the face of one of the worst beginnings—a beginning which had been so filled with boasting that his wingmates hadn’t been able to stand it. But Orth hadn’t thought of all his talk as boasting, because he had invariably made good on it. However, someone had brought home to him the fact that brave, efficient men were usually modest and really silent, and he had shut his mouth like a trap from that moment on.