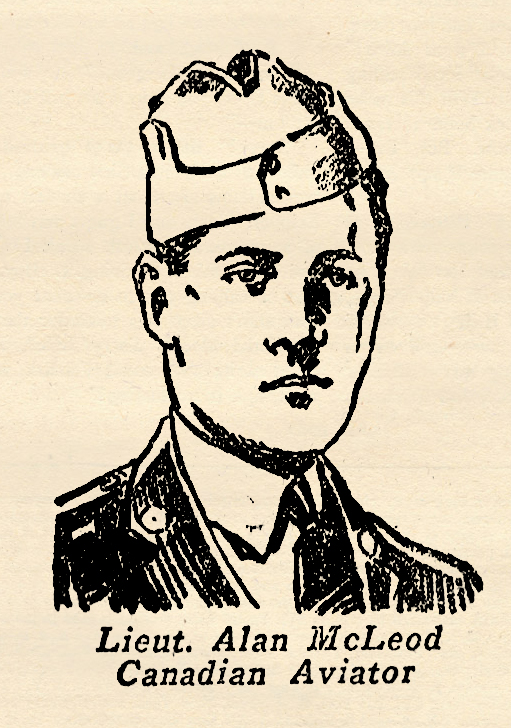

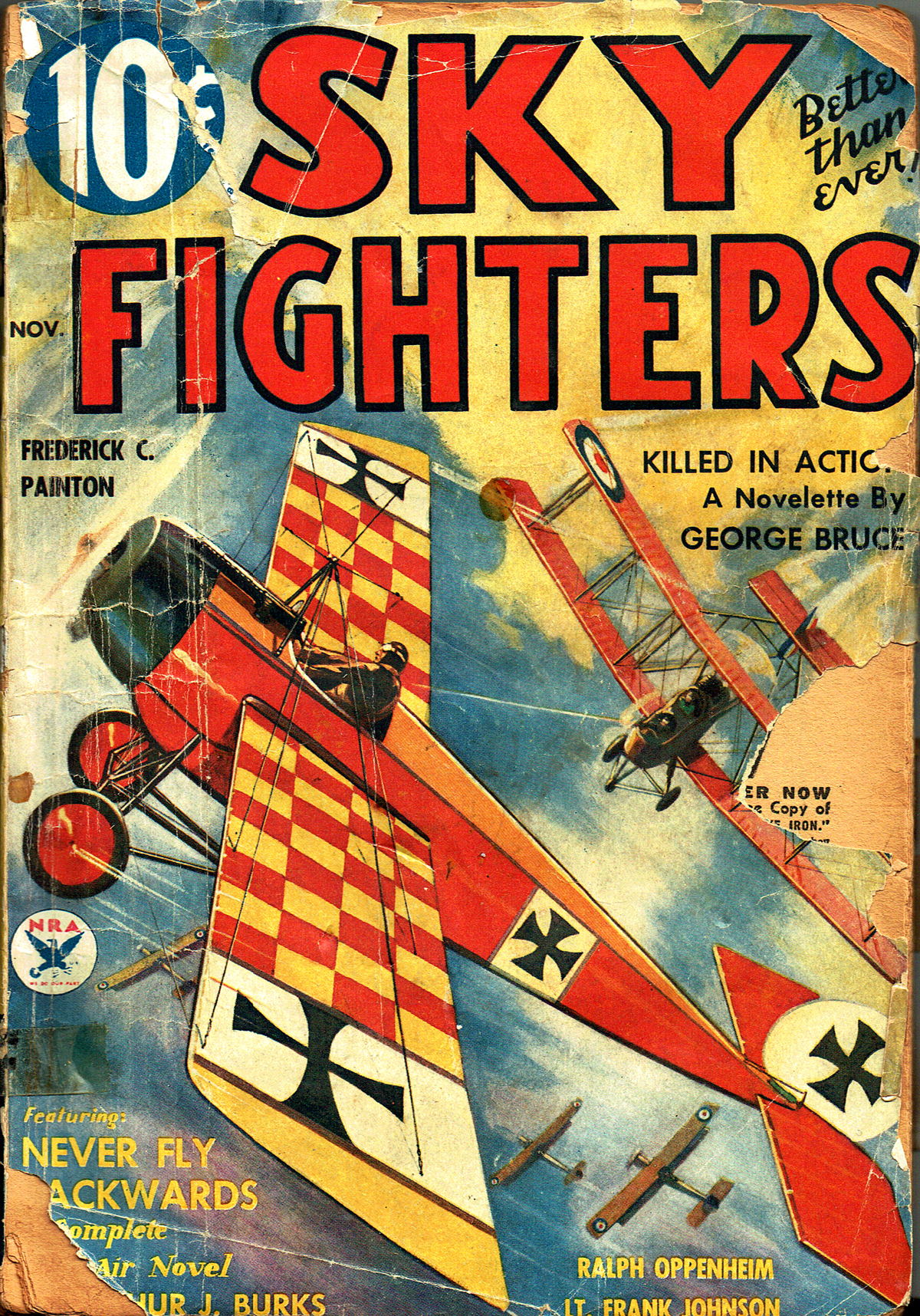

My Most Thrilling Sky Fight: Lieut. Alan McLeod, R.F.C.

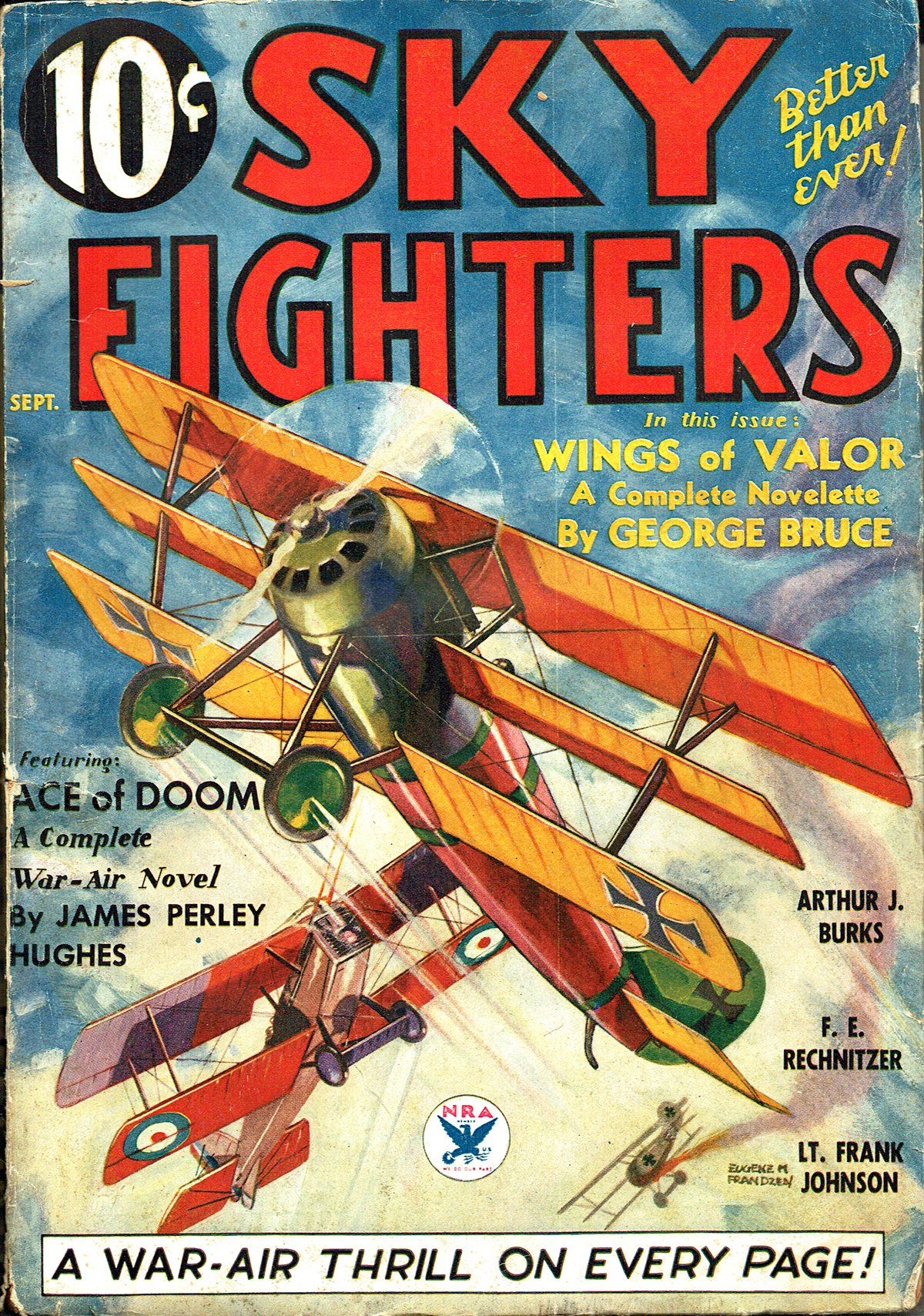

Amidst all the great pulp thrills and features in Sky Fighters, they ran a true story feature collected by Ace Williams wherein famous War Aces would tell actual true accounts of thrilling moments in their fighting lives! This time we have Canada’s Lieutenant Alan McLeod’s most thrilling sky fight!

Alan McLeod was one of  the three Canadian airmen winning the coveted award of the Victoria Cross, the highest honor bestowed on its fighting heroes by the British Empire, He was the youngest flyer ever to receive the honor, having it pinned on his chest in appropriate ceremonies at Buckingham Palace a few months before his nineteenth birthday.

the three Canadian airmen winning the coveted award of the Victoria Cross, the highest honor bestowed on its fighting heroes by the British Empire, He was the youngest flyer ever to receive the honor, having it pinned on his chest in appropriate ceremonies at Buckingham Palace a few months before his nineteenth birthday.

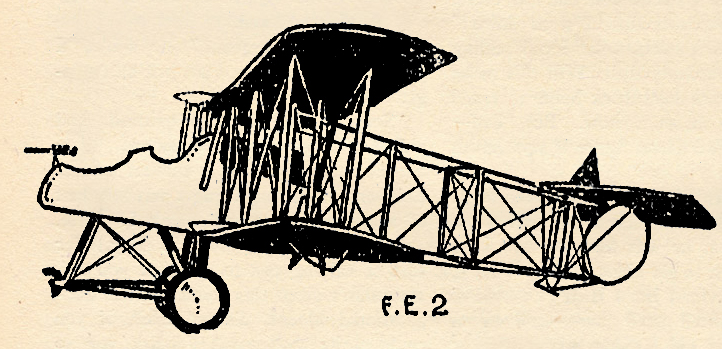

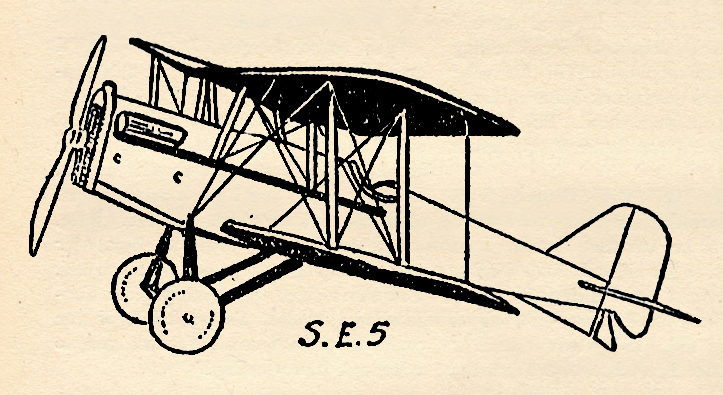

Whereas most of the other British airmen who received this coveted honor accomplished their deeds of heroic valor in fast, single-seater fighting machines, young McLeod used a heavy, unwieldy, Armstrong-Whitworth two-seater which was poorly equipped for air combat. But Alan McLeod used it just as though it were a pursuit ship, never running from a possible chance lo shoot it out with enemy planes in the air, no matter how heavy the odds were against him. The fight he tells about below is one of the great epics of the air. McLeod was wounded six times, but recovered, only to succumb to influenza five days before the armistice was signed.

DOWN IN FLAMES

by Lieut. Alan McLeod, R.F.C. • Sky Fighters, June 1934

WHEN zooming up after dropping my last bomb, I saw a Hun Fokker, coming at me from the rear. I swung my machine up on one wing, gave my observer, Hammond, in the back seat, a chance at it. His first burst of Lewis fire was effective. It went fluttering down like a falling leaf, swaying from side to side.

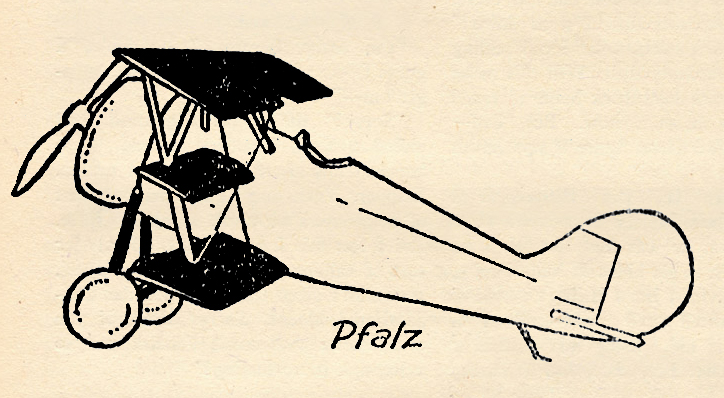

I climbed for altitude then. At 5,000 feet the sun broke through the clouds. A flight of eight scarlet-painted Fokker tripes burst through with the sun. One dived, then zoomed up under my tail. I banked steeply. Hammond got his guns on it just as the Hun let go with a burst that crackled through the lower wing just beyond my head. It went spiralling down, a black smoke trail pluming behind it.

The seven other Fokker tripes dived in with a vengeance then, attacking from all sides, and simultaneously! The air was full of German tracer. My wings were sieved. Flying wires snapped, coiled up like watch springs. I felt something like a hot knife slide across my stomach. A red shape flashed down in front of me. I pressed my gun triggers, sent in a withering burst of lead that seemed to splatter like a pinwheel as it hit. More struts on my plane cracked, shattered, sheared in two from Spandau bursts. A sharp pain stabbed me in the groin. But the red Fokker went to pieces in the air, tumbled down beneath me.

I glanced back. Tracer streams from two Fokkers were pouring at Hammond. One of his arms was hanging limply. Blood saturated his mitten. He was aiming his Lewis’ with the other hand. I went around in a sweeping, climbing turn, to get him above the attackers. Our plane groaned, crackled some more. More holes appeared like lightning in the upper wing, the lower. Another sharp pain stabbed through my lower right leg. A burst of German tracer found my petrol tank, it puffed into flames. I got in a final shot at a red Hun who swept across my path. He went down, out of control.

The heat from the burning tank lashed back in my face. Flames, choking smoke swirled in the cockpit. I loosened my belt, stepped out on the lower left wing. Holding on with my left hand, moving the stick with my right, I threw the machine into a steep side-slip, blowing the flames and smoke away from us.

Two Fokkers slid down with us, firing as they came.

Hammond, weak and reeling in the back pit, got one of them just before we hit the ground, then climbed up on the top wing. The machine crashed, thudded, bounced, throwing me off. Hammond was swept back into his pit. Flames and smoke enveloped him, the whole machine.

I raced back, pulled him out, carried him away from the fire. Bullets thudded around us, machine-gun and rifle bullets from the Huns in their trenches, not two hundred yards away,

I kept going away from them until a deep blackness descended. That is all I remember.

of that small number of American aviators who had actually had front line battle experience when his own country entered the war. Even before there were any indication* of his own country taking part, he sailed for France and enlisted in the French Army, where he was eventually transferred for aviation tralning. When the La Fayette Escadrille was formed, he wan invited to become a member. In that organization he won his commission as a Lieutenant in recognition of his ability and courage.

of that small number of American aviators who had actually had front line battle experience when his own country entered the war. Even before there were any indication* of his own country taking part, he sailed for France and enlisted in the French Army, where he was eventually transferred for aviation tralning. When the La Fayette Escadrille was formed, he wan invited to become a member. In that organization he won his commission as a Lieutenant in recognition of his ability and courage. we have a tale from the anonymous pen of Lt. Frank Johnson—a house pseudonym. Sky Fighters ran a series of stories by Johnson featuring a pilot who who was God’s gift to the Ninth Pursuit Fighter Squadron and although he says he’s a doer and not a talker, he wasn’t to shy to tell them all about it. Which earned him the nickname “Silent” Orth. This time Silent Orth goes after Baron Rapunzel—a Boche Ace who’s already claimed 51 victories—and Orth doesn’t plan to be the 52nd!

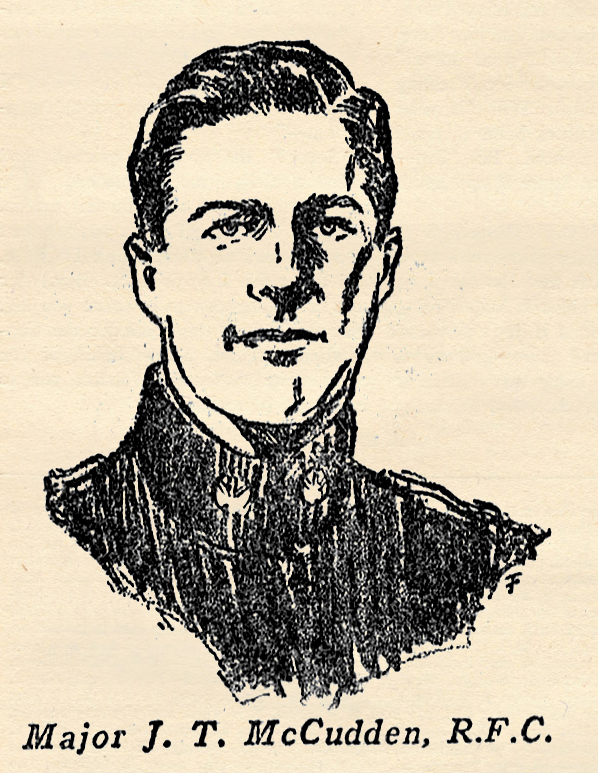

we have a tale from the anonymous pen of Lt. Frank Johnson—a house pseudonym. Sky Fighters ran a series of stories by Johnson featuring a pilot who who was God’s gift to the Ninth Pursuit Fighter Squadron and although he says he’s a doer and not a talker, he wasn’t to shy to tell them all about it. Which earned him the nickname “Silent” Orth. This time Silent Orth goes after Baron Rapunzel—a Boche Ace who’s already claimed 51 victories—and Orth doesn’t plan to be the 52nd!  one of the most modest and unassuming of the great flying aces. When the war began he was an engine mechanic with the then recently formed Royal Flying Corps. After flying training he became a Sergeant pilot, and began, piling up the string of victories which eventually placed him at the top of all the British aces. He was progressively promoted to Lieutenant, Captain and Major, and won every medal possible, including the Victoria Cross.

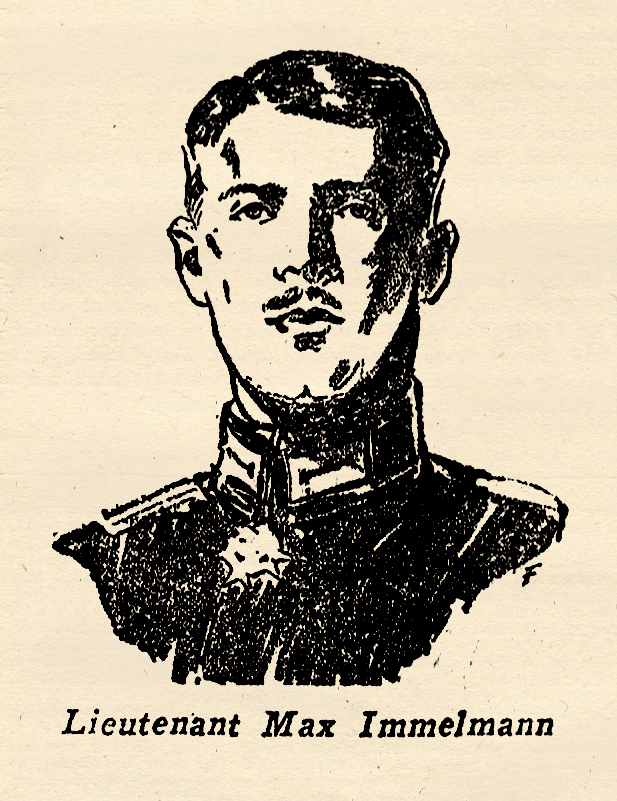

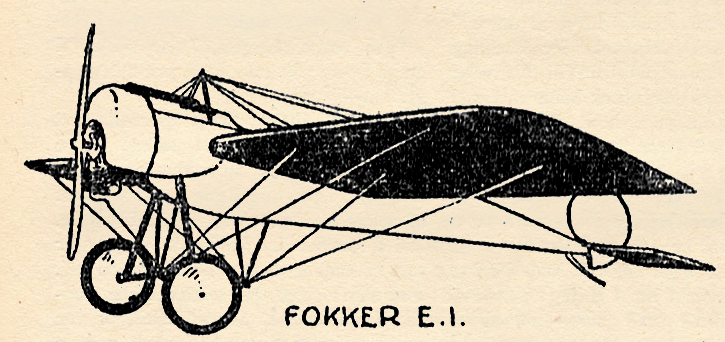

one of the most modest and unassuming of the great flying aces. When the war began he was an engine mechanic with the then recently formed Royal Flying Corps. After flying training he became a Sergeant pilot, and began, piling up the string of victories which eventually placed him at the top of all the British aces. He was progressively promoted to Lieutenant, Captain and Major, and won every medal possible, including the Victoria Cross. Immelmann was the first of the great German Aces. Immelmann scored victory after victory over the Allied flyers until his total score mounted higher than that of any of the Allied Aces.

Immelmann was the first of the great German Aces. Immelmann scored victory after victory over the Allied flyers until his total score mounted higher than that of any of the Allied Aces. we have a tale from the anonymous pen of Lt. Frank Johnson—a house pseudonym. Sky Fighters ran a series of stories by Johnson featuring a pilot who who was God’s gift to the Ninth Pursuit Fighter Squadron and although he says he’s a doer and not a talker, he wasn’t to shy to tell them all about it. Which earned him the nickname “Silent” Orth.

we have a tale from the anonymous pen of Lt. Frank Johnson—a house pseudonym. Sky Fighters ran a series of stories by Johnson featuring a pilot who who was God’s gift to the Ninth Pursuit Fighter Squadron and although he says he’s a doer and not a talker, he wasn’t to shy to tell them all about it. Which earned him the nickname “Silent” Orth.  American Ambulance section, serving in that unit attached to the French armies from February 26th, 1916, to May 11th, 1918. In the early spring of ‘18 he transferred to the aviation. He became a member of the famous Stork squadron of the French Flying Corps.

American Ambulance section, serving in that unit attached to the French armies from February 26th, 1916, to May 11th, 1918. In the early spring of ‘18 he transferred to the aviation. He became a member of the famous Stork squadron of the French Flying Corps.

Donald McLaren was born in Ottawa, Canada, in 1893, but at an early age his parents moved to the Canadian Northwest, where he grew up with a gun in his hands. He got his first rifle at the age of six, and was an expert marksman by the time he was twelve. When the war broke out he was engaged in the fur business with his father, far up in the Peace River country. He came down from the north in the early spring of 1917 and enlisted in the Canadian army, in the aviation section. He went into training at Camp Borden, won his wings easily and quickly, and was immediately sent overseas. In February, 1918, he downed his first enemy aircraft. In the next 9 months he shot down 48 enemy planes and 6 balloons, ranking fourth among the Canadian Aces and sixth among the British. No ranking ace in any army shot down as many enemy aircraft as he did in the same length of time. For his feats he was decorated with the D.S.O., M.C., D.F.C. medals of the British forces, and the French conferred upon him both the Legion d’Honneur and Croix de Guerre. Oddly, just before the war ended, he was injured in a wrestling match with one of his comrades and spent armistice day in a hospital nursing a broken leg. He had gone through over a hundred air engagements without receiving a scratch. The air battle he describes below is unusual because almost 100 planes took part in it.

Donald McLaren was born in Ottawa, Canada, in 1893, but at an early age his parents moved to the Canadian Northwest, where he grew up with a gun in his hands. He got his first rifle at the age of six, and was an expert marksman by the time he was twelve. When the war broke out he was engaged in the fur business with his father, far up in the Peace River country. He came down from the north in the early spring of 1917 and enlisted in the Canadian army, in the aviation section. He went into training at Camp Borden, won his wings easily and quickly, and was immediately sent overseas. In February, 1918, he downed his first enemy aircraft. In the next 9 months he shot down 48 enemy planes and 6 balloons, ranking fourth among the Canadian Aces and sixth among the British. No ranking ace in any army shot down as many enemy aircraft as he did in the same length of time. For his feats he was decorated with the D.S.O., M.C., D.F.C. medals of the British forces, and the French conferred upon him both the Legion d’Honneur and Croix de Guerre. Oddly, just before the war ended, he was injured in a wrestling match with one of his comrades and spent armistice day in a hospital nursing a broken leg. He had gone through over a hundred air engagements without receiving a scratch. The air battle he describes below is unusual because almost 100 planes took part in it.