“Some Inside Dope on the Flying Industry” by William E. Barrett

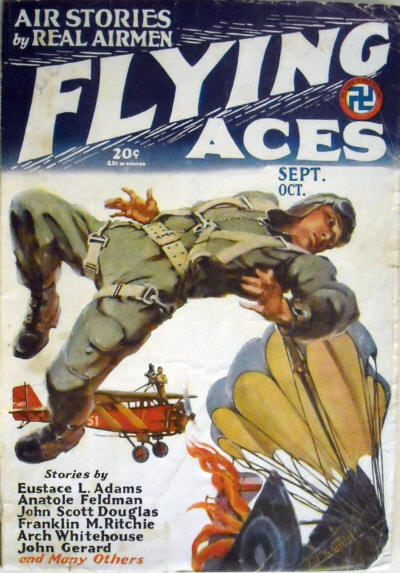

IN LOOKING through the  September 1929 issue of Flying Aces for last week’s exciting tale of Handley Page bombers by Arch Whitehouse, the letters page had a lengthy letter addressed to the publisher Harold Hersey himself from William E. Barrett titled “Some Inside Dope on the Flying Industry.”

September 1929 issue of Flying Aces for last week’s exciting tale of Handley Page bombers by Arch Whitehouse, the letters page had a lengthy letter addressed to the publisher Harold Hersey himself from William E. Barrett titled “Some Inside Dope on the Flying Industry.”

Here is that letter:

Mr. Harold Hersey

Editor: FLYING ACES.

Dear Mr. Hersey:

Back in 1914, a young man who had designed and flown his own plane while still in high school went to call on another young man who had just won considerable attention by designing the first airplane in America to fly with a motorcycle engine.

At that meeting a friendship was born that has endured through all of the years that have intervened since; it was the first contact of two careers that were fated to parallel and interweave through all of the long struggle which resulted in the “flying game” becoming the “aviation industry. The meeting took place in California and today, Richard Hardin, the caller, and Derek White, the young inventor, are together as the moving spirits of the Guardian Aircraft Corporation of St. Louis.

There Is a lot of color and romance In these two careers which have been woven into the strange pattern from which the aviation industry was cut. Pilots, designers, instructors; the two men moved in different localities and lost sight of each other for years And yet continued to climb in the same direction: contributing much to aviation as they climbed.

In 1913, White had become a serious student of aviation while with the Glenn L. Martin Company, government contractors. At that time the field was wide open to the experimenter and there was little public interest except in the “stunts” and the novelty features of flying.

White experimented with a motorcycle motor and a light plane. His experiments were successful and he had the thrill of flying his own ship in a day when very few men had even experienced the thrill of being “aloft.” About the same time, A.V. Roe, who was ultimately to win fame as the designer of the famous Avro plane of war history, was conducting similiar experiments in England. He, too, was successful.

Hardin was still in high school; an adventurous youth who was greatly impressed with the studies of bird flight, conducted by the physics professor, H LaV. Twining, designer of the Twining Ornithopter, a plane that operated with flapping wings. He, too, succeeded in building and flying a ship of his own design and when word of White’s achievement reached him, he waa anxious to meet this other pioneer and compare experiences.

“Right there at that meeting,” says Hardin, “I cemented my decision to make flying my life work. It was hard to see any future in it at that time but after White and I talked it over, I caught a flash of his enthusiasm. I have never regretted it.”

For the next few years the trails of the two experimenters diverged. White started his own airplane plant and operated it under the name of the White Aircraft Works daring the years 1915, and 16. It was a losing venture, in the long run, as the public was not yet ready to accept aviation as a serious factor in the life of the Nation. Hardin, during this time, was a member of the National Guard of California and was continuing his experiments with new designs, many of which he later used. He built and flew several ships of his own In these years, but like White, found very-little profit in the game.

Late in 1916 and in 1917. White temporarily deserted aviation but couldn’t get far away from it. The thrill of speed and motion and adventure was in his blood. He went into the auto racing game and drove a Mercer on all of the big tracks of the West; Los Angeles, Bakersfield, Phoenix, etc. In between races, he designed the first trimotor monoplane in the United States for the proposed trans-Paciflc flight of Lieutenant W.P. Finlay.

It is a good indication of conditions at the time that the plane was never finished because of the lack of financial backing. The attempt, however, started something. Up till that time no one had ever put a tri-motored monoplane on paper. From then on many designers experimented with this type of ship and today the greatest transport planes are of this type.

April of 1917 brought the war, with opportunity for Hardin and disaster for White. The same week that war was declared, White crashed into a fence in a fiercely contested auto race in which he and Roscoe Sarles vied for public favor. The next fourteen months were spent in hospitals and on crutches.

Hardin had joined the French Flying Corps a year and a half before the United States entered the war, with the hope of getting into the famous Lafayette Escadrille. He was disappointed in this ambition but he saw plenty of air action with a French Chasse squadron assigned to the front line.

His office in the Guardian Aircraft Plant today is decorated with pictures drawn by an artistic buddy of his, showing him in action at the front and hailing him as the “greatest trench straffer of them all.” He left the French service with the “Croix de guerre with one palm and with the medal militaire.”

During his convalescence, White turned to his skill with the pen for a living while more active pursuits were denied him. Newspaper and sales promotion work enabled him to carry on during this period and he worked for such accounts as Durant Motor, Pennzoil and the Columbia Tire Corporation. He also scored a newspaper scoop that was notable on the Pacific Coast, obtaining pictures of the take-off in the Navy flight to Hawaii, the P.N.1 and P.N.3, in the face of the official ban on photographers. These were the only pictures obtained.

Hardin, reluctant to abandon a military career that had allowed him a full measure af flying and adventure, went to Morocco with the Sheriffian Escadrille, composed mostly of American adventurers. This was a bombing unit flying under the colors of the Sultan in French bombing planes. It is credited with performing a notable part in the conquering of Abdel Krim.

The interval between his service in the two wars was filled by a year of design work with the Ordinance Engineering Corporation, builders of the Orenco plane. After the Riff excitement he returned to California and entered the employ of the Douglaa Company at Santa Monica, builders of the Douglas torpedo plane. He was instrumental here in the designing of several outstanding special planes built by the Douglaa people.

Meanwhile White was resisting the lure of aviation and building up a successful advertising agency on the basis of his service accounts.

“I did not, however, drop it as a fascinating hobby,” he says, “I continued to design planes and fly them. I could see, however, that at that time, it would take patience and capital to make money out of this new industry. I had the patience and I used it to get the capital.”

In 1926 the chance that he had been waiting for came. He got the opportunity of combining his knowledge of aviation with his sales promotion and business experience. Colonel G.C.R. Mumby, formerly in command of the Western Repair Depot in France and production officer in the British Air Service during the war, went into partnership with Charles A. Warren for the purpose of establishing a school on the West Coast. White was called in to lay out the plans for the school and to handle the advertising and publicity.

Here, for the first time since they met in 1914, the trails of Hardin and White again crossed. Hardin, fresh from an enlistment in the Navy where he had trained flying cadets and won his bars as Engineering officer assigned to the Admiral’s staff, came to the Warren School as Chief engineer and Supervisor of Instruction.

White, however, did not remain long with the Warren School. His success as a pro-motor was so phenomenal that in 1927 he was sought by the Nicholas Beazley Airplane Company of Marshall, Missouri. He accepted the appointment as General Sales Manager of this concern and also established the Marshall Flying School. This school was an immediate success and Destiny prepared to deal a new hand to Derek White.

In the latter part of 1927 Oliver L. Parks and Harry P. Mammen conceived the idea of an Air College, using a field across the river and closer to the City of St. Louis than any field on the Missouri side could posslbly be. They sought a high grade promoter with experience as an instructor and organizer. All trails led to White. In February, 1928, he took charge of the newly organized Parks Air College under terms which led the organizers to bill him as “the highest priced air school executive in the United States.”

Parks Air College was a “natural.” At the end of six months it had signed more students than any school had ever signed in the history of aviation. A whole fleet of planes had been built up to meet the demands of the increasing army of students and the organizers of the College started to look around for new fields to conquer. They decided to build their own plane, and Parks Aircraft Corporation was born.

Once more Destiny tangled the skeins of two careers that had started practically side by side. A wire to California brought Lieutenant “Dick” Hardin on the scene to become Chief engineer of the new Company and Superintendent of all ground school activities.

By October the Parks Air College hud become the largest commercial flying school in the world and White became restless. The job for which he had contracted was done as far as he was concerned and there was no more thrill of the “uphill drag.” With his own capital he established the Guardian Aircraft Corp. and opened an office and small plant in St. Louis.

Hardin joined him in the new venture and in January, at the expiration of his contract with Parks Air College, White moved the Guardian Company to larger querters, at 2500 Texas Ave. He Incorporated, and with Hardin as his Chief engineer, settled down to the designing of a plane which would sell for two thousand dollars.

Today, the plane is emerging rapidly from the blue prints and taking on form under the hammer, the saw, the welder and the plane. The skeleton is spreading out and it is planned to have the plane ready for test by the middle of August. Already fifteen orders for Guardian monoplanes have been received unsolicited, sight unseen, from people who know and have confidence in the sponsors. A flood of inquiries and requests for dealerships are also being received daily.

That isn’t the whole story, though. No plant that Derek White is connected with would bo complete without a school; so the Guardian Ground School has been organised on a principle so different from any aviation school now in existence that it has been seized on avidly by the aviation trade publications as a new development within the industry.

“The idea for the school was a logical outgrowth of my own career,” says White. “I have served in every branch of the industry and I have been alarmed at the tendency to emphasize the rewards and the glamour of flying and to paint a picture of aviation as a ‘game.’

“It isn’t anything of the kind; it is an industry, the fastest growing industry in the world. It doesn’t need adventurers nearly as badly as it needs business men. That is what we are going to turn out in our school; men trained in the business of aviation. In addition to the usual ground work—design, engineering, maintenance, meteorology and all that, we are going to teach them selling, advertising, production and finance. We have the best laboratory possible by allowing them to work with us in the solving of the problems which arise in our own plant.”

There you are. Two men who have tasted practically everything that aviation holds maintain that its biggest rewards are going to go to the men who stay on the ground and are building a school to prove it. That is a new thought for the youth who wants to get into the “Air” business.

Yours truly,

William E. Barrett

207 Stroh Bldg.,

4641 Delmar Blvd., St. Louis, Mo.

Here’s an ad for White’s Guardian Ground School from the April 1929 issue of

Popular Aviation and Aeronautics!