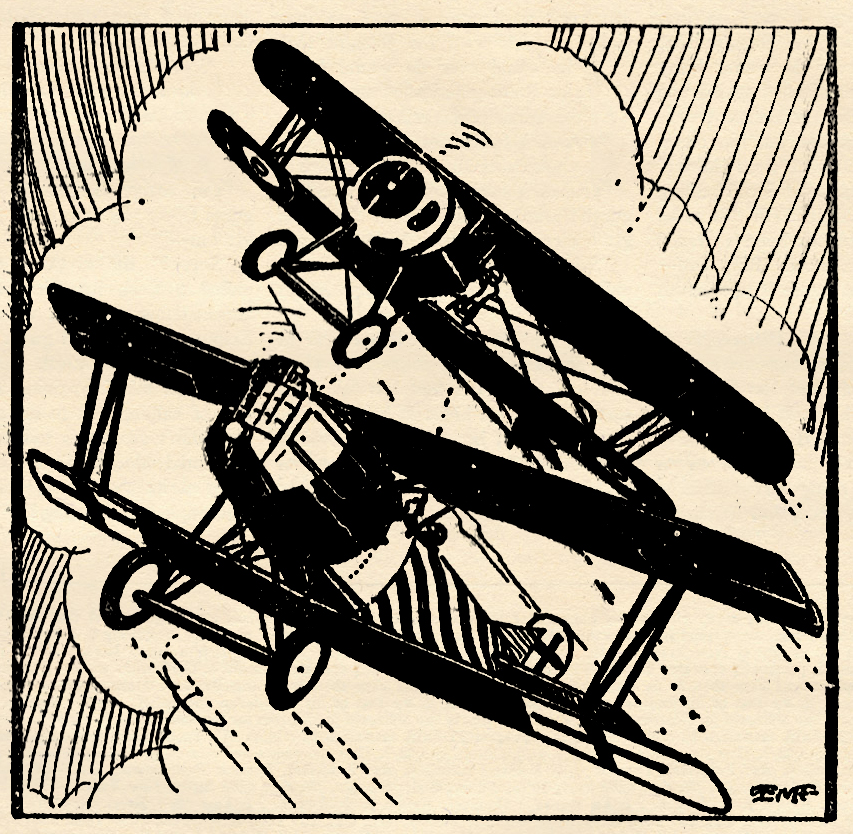

The Lone Eagle, May 1936 by Eugene M. Frandzen

Eugene M. Frandzen painted the covers of The Lone Eagle from its first issue in September 1933 until the June 1937 issue when he would share duties with Rudolph Belarski. At the start of the run, Frandzen painted covers of general air action much like his Sky Fighters covers, shifting to covers featuring famous aces at the end of 1935. For the May 1936 issue, Frandzen gives us a Nieuport 28 and Pfalz D3 locked in combat!

The Story of the Cover

SOME planes had famous  ancestors whose reputations had to be upheld. The Nieuport line was of the French aristocracy of war planes. The early Nieuport scouts were named “avions de chasse.†They were to the world war what the cavaliers clad in shining armour riding prancing Arabian horses were to the Middle Ages. The end of the war saw the Nieuport 28C1, a single-seater fighter, which made those American pilots speak of this plane with affection almost twenty years after the war.

ancestors whose reputations had to be upheld. The Nieuport line was of the French aristocracy of war planes. The early Nieuport scouts were named “avions de chasse.†They were to the world war what the cavaliers clad in shining armour riding prancing Arabian horses were to the Middle Ages. The end of the war saw the Nieuport 28C1, a single-seater fighter, which made those American pilots speak of this plane with affection almost twenty years after the war.

The Germans had the Pfalz line of single-seater planes whose ancestry was not so clear. The early Pfalz D3 in fact had so many characteristics of the Nieuport of its time that it has not been free from the slur of being a copy. The Pfalz D13 of 1918 tried to save the family name by having a design all its own.

A Brilliant Ace

Frank L. Baylies was a member of the old Lafayette Escadrille. He was invited to join the Stork squadron of French veteran fighters. This young American airman was a brilliant star in a firmament of older aces. Baylies had twelve official victories credited to his skill in less than six months. The courageous qualities that endeared him to his comrades led him into an ambush on June 17, 1918. Flying well in German territory he attacked three enemy ships but a fourth German plane lurking above unseen came down on Baylies from the rear. Baylies’ plane fell in German territory.

The details of his last fight are clouded in the mystery of war, but the memory of one of America’s most intrepid airmen lives as a shining glory.

Prisoners of war were not always treated as “enemies†on our side of the lines. Usually they were steered to a liquid-soaked plank on which sundry bottles, glasses and other necessary drinking paraphenalia reposed.

Cognac and vintage wines skidded over appreciative palates. Any differences of opinion went by the board. After that. Max, Fritz or Oscar was merely on the wrong side of the argument, but he was a flyer and deserved a square deal before being thrown into clank for the duration of the war.

Such a situation arose one day when a wobbling German plane was forced down adjacent to a Yank drome. He was in one piece and thirsty. He sang a good bass to “Sweet Adeline.†He held his liquor like a gentleman and he could run like Nurmi.

He demonstrated this fact by grabbing the only .45 automatic in the crowd and sprinting across the flying field, hopping into a Nieuport 28 and getting off the field fifty yards ahead of a Yank who was testing a captured Pfalz D13 which had a trick Fokker tail in its rear section. Neither of the ships had ammo.

Duelling in Darkness

Both aviators had side arms, A cockeyed duel ensued as darkness began to fall. Two powerful planes heeled with pea shooters. They blazed at each other industriously. They did not see three cruising Allied planes rushing at them, nor did they see three German planes until the half dozen ships broke in on their private scrap with a bang. The German pilot in the Nieuport shrugged his shoulders and snuggled in among the Allied planes. The Yank took his lead and flipped his Pfalz among the Germans. Both foursomes veered off and headed for their own lines. The two revolver dueling airmen raised imaginary glasses to their lips; toasted each other, then as dusk crept deeper over the blurred formations, cut out and headed for their own lines.

As they passed each other at combined speeds of about 280 miles per hour, they let go a final parting shot from their pea shooters, a friendly salute till they could get a few assorted machine-guns anchored on the top cowling and go after this business of killing each other in a really serious manner.

The Lone Eagle, May 1936 by Eugene M. Frandzen

(The Story of The Cover Page)